14 Module 14: Motivation, Stress and Coping

Module 14 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Define Motivation

Explain the concept of motivation and differentiate between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. - Understand Theories of Motivation

Describe major theories of motivation, including Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, drive-reduction theory, and incentive theory. - Explain Overjustification Effect

Discuss the overjustification effect and how extrinsic rewards can impact intrinsic motivation. - Explore Motivational Interviewing

Explain the principles and applications of motivational interviewing, including its role in patient-centered care. - Analyze Stress

Define stress, distinguish between eustress and distress, and describe the factors that influence stress experiences. - Examine Types of Stressors

Differentiate between acute and chronic stressors, and identify examples of life changes, daily hassles, and traumatic events. - Understand the General Adaptation Syndrome

Explain the stages of Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion. - Discuss Psychophysiological Disorders

Identify common psychophysiological disorders and explain how stress contributes to their development. - Examine the Role of Social Support

Describe the benefits of social support in reducing stress and promoting physical and mental health. - Understand the Impact of Stress on the Immune System

Explain how chronic stress affects immune functioning and increases vulnerability to illness. - Explore Coping Strategies

Define coping and differentiate between problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance coping strategies. - Analyze Learned Helplessness

Discuss the concept of learned helplessness and its relationship to stress, control, and mental health outcomes. - Understand Resilience

Explain the factors that contribute to resilience and how it helps individuals cope with stress. - Identify Stress Management Techniques

Describe strategies for managing stress, including exercise, relaxation techniques, and biofeedback. - Discuss Cultural Influences on Stress and Coping

Analyze how cultural factors influence stress perception and preferred coping strategies. - Apply Motivation and Stress Concepts

Use theories of motivation and coping to analyze real-life scenarios and improve personal or professional practices.

Motivation

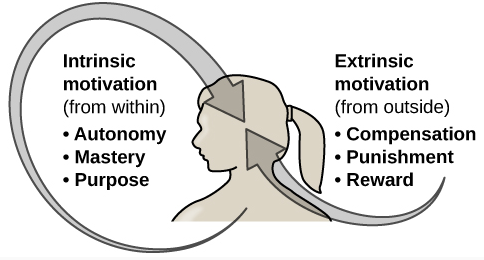

Why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Why are you reading this textbook? Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with activities that are challenging, yet doable, along with a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Consider Hakim, a first-year law student with two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. The majority of the course grade is not exam-based, but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

While some theories suggest that people are driven by internal forces, incentive theory proposes that it is the desire to gain rewards and avoid punishments that causes our behavior. Incentive theory is rooted in the work of behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner. In Skinner’s operant conditioning theory, reinforcement increases behavior while punishment decreases it.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Some research suggests that this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). According to this research, receiving some sort of extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it. What Odessa has experienced is called the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing the intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

A classic research study of intrinsic motivation illustrates this problem clearly. In the study, researchers asked university students to perform two activities—solving puzzles and writing newspaper headlines—that they already found interesting. Some of the students were paid to do these activities, the others were not. Under these conditions, the students who were paid were less likely to continue to engage in these activities after the experiment, while the students who were not paid were more likely to continue—even though both groups had been equally interested in the activities to begin with. The extrinsic reward of payment, it seemed, interfered with the intrinsic reward of the activity itself.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions on the Overjustification Effect:

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation. Several factors may influence this: for one, physical reinforcements (such as money) have been shown to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do verbal reinforcements (such as praise). Furthermore, the expectation of the extrinsic motivator by an individual is crucial: if the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If, however, there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist. Adding to the complexity, other studies suggest reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to care for others might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her skills of connecting with others and thoughtfulness.

Some studies provide evidence that the effectiveness of extrinsic motivators varies depending on factors like self-esteem, locus of control (the extent to which someone believes they can control events that affect them), self-efficacy (how someone judges their own competence to complete tasks and reach goals), and neuroticism (a personality trait characterized by anxiety, moodiness, worry, envy, and jealousy). For example, praise might have less effect on behavior for people with high self-esteem because they would not have the same need for approval that would make external praise reinforcing. On the other hand, someone who lacks confidence may work harder in response to it.

In addition, culture may influence motivation. For example, in collectivistic cultures, it is common to do things for your family members because the emphasis is on the group and what is best for the entire group, rather than what is best for any one individual (Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). This focus on others provides a broader perspective that considers both situational and cultural influences on behavior; thus, a more nuanced explanation of the causes of others’ behavior becomes more likely.

Motivational Interviewing

Patient education and health promotion are core nursing interventions. Motivational interviewing (MI) is a communication skill used to elicit and emphasize a client’s personal motivation for modifying behavior to promote health. MI has been effectively used for several health issues such as smoking cessation, diabetes, substance use disorders, and adherence to a treatment plan. Motivational interviewing is related to intrinsic motivation for the patient as motivational interviewing works to help people find the internal reasons they need to make changes in a behavior.

The spirit of motivational interviewing is a collaborative partnership between nurses and clients, focused on patient-centered care, autonomy, and personal responsibility. It is a technique that explores a client’s motivation, confidence, and roadblocks to change. During motivational interviewing, nurses pose questions, actively listen to client responses, and focus on where the client is now with a current health behavior and where they want to be in the future.

Motivational interviewing uses these principles:

Express empathy. Use reflective listening to convey acceptance and a nonjudgmental attitude. Rephrase client comments to convey active listening and let clients know they are being heard.

Highlight discrepancies. Help clients become aware of the gap between their current behaviors and their values and goals. Present objective information that highlights the consequences of continuing their current behaviors to motivate them to change their behavior.

Adjust to resistance. Adjust to a client’s resistance and do not argue. The client may demonstrate resistance by avoiding eye contact, becoming defensive, interrupting you, or seeming distracted by looking at their watch or cell phone. Arguing can place the client on the defensive and in a position of arguing against the change. Focus on validating the client’s feelings.

Understand motivations. Uncover a client’s personal reasons for making behavioral changes and build on them.

Support self-efficacy. Encourage the client’s optimistic belief in the prospect of change and encourage them to commit to positive behavioral changes. Ask clients to elaborate on past successes to build self-confidence and support self-efficacy.

Resist the reflex to provide advice. Avoid imposing your own perspective and advice.

When implementing motivational interviewing, it is important to assess the client’s readiness for change. Motivational interviewing is especially useful for clients in the contemplation stage who are feeling ambivalent about making change.

Recall these five stages of behavioral change:

Precontemplation: Not considering change.

Contemplation: Ambivalent about making change.

Preparation: Taking steps toward implementing change.

Action: Actively involved in the change process.

Maintenance: Sustaining the target behavior.

Identify clients who are ambivalent about making a behavioral change or following a treatment plan by listening for the phrase, “Yes, but.” The “but” holds the key for opening the conversation about ambivalence. For example, a client may state, “I want to take my medication, but I hate gaining weight.” The content in the sentence after the “but” reveals the client’s personal roadblock to making a change and should be taken into consideration when planning outcomes and interventions.

See the following box for an example of a nurse using motivational interviewing with a client:

Mr. L. had been in treatment for bipolar I disorder with medication management and supportive therapy for many years. He had a history of alcohol dependence but was in full recovery. Mr. L. was admitted to the intensive care unit with a toxic lithium level. He had been seen in the emergency room the preceding evening and was noted to have a very high blood alcohol level. The next day the nurse asked the client about his alcohol use using motivational interviewing.

Client: I am so sick of everyone always blaming everything on my drinking!

Nurse (Using reflective listening): You seem pretty angry about the perception that you were hospitalized because you had been drinking.

Client: You better believe it! I am a man! I can have a few drinks if I want to!

Nurse: (Expressing empathy and acceptance): You want to be respected even when you are drinking.

Client: I have had some trouble in the past with drinking, but that is not now. I can quit if I want to! Compared to what I used to drink, this is nothing.

Nurse (Rolling with resistance): So you see yourself as having had drinking problems in the past, but the drinking you’ve done recently is not harmful for you.

Client: Well, I guess I did end up in the hospital.

Nurse (Using open-ended questioning): Tell me more about what happened.

Client: I was pretty angry after an argument with my girlfriend, and I decided to buy a bottle of whiskey.

Nurse (Exploring): And then?

Client: Well, I meant to have a couple of shots, but I ended up drinking the whole fifth. I really don’t remember what happened next. They said I nearly died.

Nurse (Summarizing): So after many years of not drinking, you decided to have a couple of drinks after the argument with your girlfriend, but unintentionally drank enough to have a blackout and nearly die.

Client: I guess that does sound like a problem…but I don’t want anyone else telling me whether or not I can drink!

Nurse (Emphasizing autonomy): Tell me how the choice to drink or not continues to support or oppose your health goals.

Drive Reduction Theories

Another early theory of motivation proposed that the maintenance of homeostasis is particularly important in directing behavior. You may recall from your earlier reading that homeostasis is the tendency to maintain a balance, or optimal level, within a biological system. In a body system, a control center (which is often part of the brain) receives input from receptors (which are often complexes of neurons). The control center directs effectors (which may be other neurons) to correct any imbalance detected by the control center.

According to the drive theory of motivation, deviations from homeostasis create physiological needs. These needs result in psychological drive states that direct behavior to meet the need and, ultimately, bring the system back to homeostasis. For example, if it’s been a while since you ate, your blood sugar levels will drop below normal. This low blood sugar will induce a physiological need and a corresponding drive state (i.e., hunger) that will direct you to seek out and consume food ([link]). Eating will eliminate the hunger, and, ultimately, your blood sugar levels will return to normal. Interestingly, drive theory also emphasizes the role that habits play in the type of behavioral response in which we engage. A habit is a pattern of behavior in which we regularly engage. Once we have engaged in a behavior that successfully reduces a drive, we are more likely to engage in that behavior whenever faced with that drive in the future (Graham & Weiner, 1996).

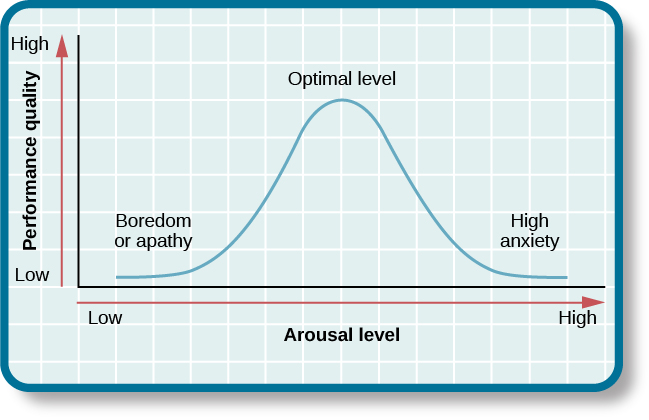

Extensions of drive theory consider levels of arousal as potential motivators. As you recall from your study of learning, these theories assert that there is an optimal level of arousal that we all try to maintain. If we are underaroused, we become bored and will seek out some sort of stimulation. On the other hand, if we are overaroused, we will engage in behaviors to reduce our arousal (Berlyne, 1960). Most students have experienced this need to maintain optimal levels of arousal over the course of their academic career. Think about how much stress students experience toward the end of spring semester. They feel overwhelmed with seemingly endless exams, papers, and major assignments that must be completed on time. They probably yearn for the rest and relaxation that awaits them over the extended summer break. However, once they finish the semester, it doesn’t take too long before they begin to feel bored. Generally, by the time the next semester is beginning in the fall, many students are quite happy to return to school. This is an example of how arousal theory works.

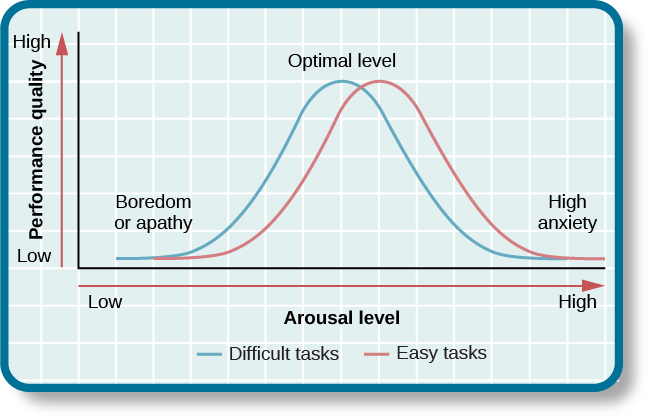

So what is the optimal level of arousal? What level leads to the best performance? Research shows that moderate arousal is generally best; when arousal is very high or very low, performance tends to suffer (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). Think of your arousal level regarding taking an exam for this class. If your level is very low, such as boredom and apathy, your performance will likely suffer. Similarly, a very high level, such as extreme anxiety, can be paralyzing and hinder performance. Consider the example of a softball team facing a tournament. They are favored to win their first game by a large margin, so they go into the game with a lower level of arousal and get beat by a less skilled team.

But optimal arousal level is more complex than a simple answer that the middle level is always best. Researchers Robert Yerkes (pronounced “Yerk-EES”) and John Dodson discovered that the optimal arousal level depends on the complexity and difficulty of the task to be performed. This relationship is known as Yerkes-Dodson law, which holds that a simple task is performed best when arousal levels are relatively high and complex tasks are best performed when arousal levels are lower. Generally then, task performance is best when arousal levels are in a middle range, with difficult tasks best performed under lower levels of arousal and simple tasks best performed under higher levels of arousal.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

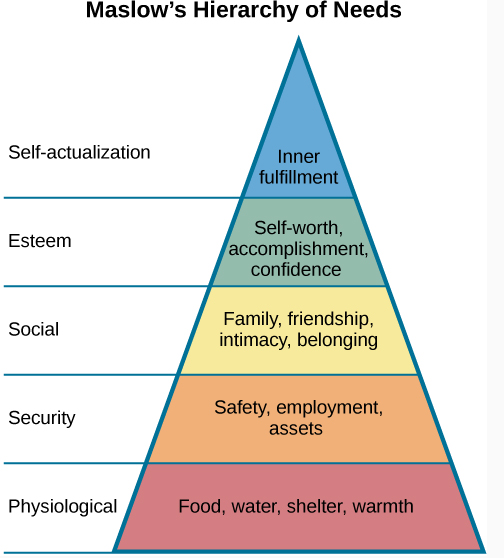

Abraham Maslow (1943) proposed a hierarchy of needs that spans the spectrum of motives ranging from the biological to the individual to the social. These needs are often depicted as a pyramid. At the base of the pyramid are all of the physiological needs that are necessary for survival. These are followed by basic needs for security and safety, the need to be loved and to have a sense of belonging, and the need to have self-worth and confidence. The top tier of the pyramid is self-actualization, which is a need that essentially equates to achieving one’s full potential, and it can only be realized when needs lower on the pyramid have been met. To Maslow and humanistic theorists, self-actualization reflects the humanistic emphasis on positive aspects of human nature. Maslow suggested that this is an ongoing, life-long process and that only a small percentage of people actually achieve a self-actualized state (Francis & Kritsonis, 2006; Maslow, 1943).

According to Maslow (1943), one must satisfy lower-level needs before addressing those needs that occur higher in the pyramid. So, for example, if someone is struggling to find enough food to meet his nutritional requirements, it is quite unlikely that he would spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about whether others viewed him as a good person or not. Instead, all of his energies would be geared toward finding something to eat. However, it should be pointed out that Maslow’s theory has been criticized for its subjective nature and its inability to account for phenomena that occur in the real world (Leonard, 1982). Other research has more recently addressed that late in life, Maslow proposed a self-transcendence level above self-actualization—to represent striving for meaning and purpose beyond the concerns of oneself (Koltko-Rivera, 2006). For example, people sometimes make self-sacrifices in order to make a political statement or in an attempt to improve the conditions of others. Mohandas K. Gandhi, a world-renowned advocate for independence through nonviolent protest, on several occasions went on hunger strikes to protest a particular situation. People may starve themselves or otherwise put themselves in danger displaying higher-level motives beyond their own needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a good basis for providing holistic care and communicating with clients based on their needs and preferences. For example, in nursing, priorities of care are based on physiological needs and safety. Additionally, knowing that a newly admitted patient may have difficulty reaching a higher level of needs if their basic needs are not met is a good starting point for providing care.

Strategies that integrate Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs when providing care to clients include the following:

- Following the nursing plan of care to meet physiological needs.

- Implementing fall precautions to keep patients safe.

- Answering call lights promptly and consistently providing a calm, comfortable environment to make patients feel secure.

- Respecting patients’ belongings and asking their preferences for grooming, bathing, and meals to satisfy self-esteem needs.

- Interacting with patients as fellow human beings- asking about interests for example- when appropriate to promote a feeling of belongingness.

- Offering resources like chaplain visits or social supports to promote self-actualization and a feeling of belongingness.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs can also be applied to the work environment to enhance professionalism by doing the following:

- Helping coworkers when able to promote a feeling of security and belongingness and also maintaining patients’ physiological needs and safety as a team.

- Participating fully in the reporting and documentation process of the facility to meet patients’ physiological and safety needs.

- Accurately following training and agency policies and procedures to encourage feelings of self-esteem in the health care worker.

- Being accountable for one’s actions and job responsibilities to promote a feeling of self-actualization by meeting one’s potential.

Stress

What is Stress?

Like motivation, stress is a very individual experience. One person can feel extreme pressure and anxiety over a task that is looming, and another might look at the same task and see it as an exciting challenge. Stress is a dynamic condition, and it exists when an individual is confronted with an opportunity, constraint or demand related to what they desire, and for which the outcome is perceived to be both uncertain and important.

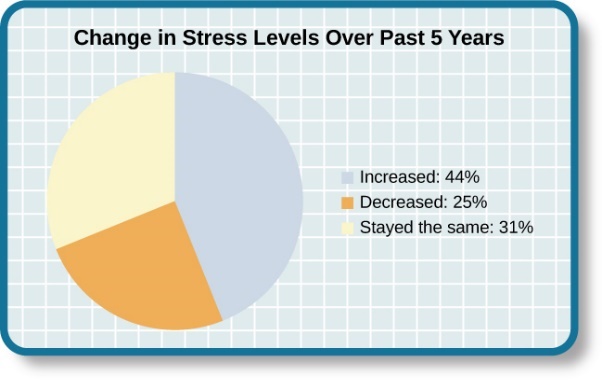

The Prevalence of Stress

Stress is everywhere and it has been on the rise over the last several years. Each of us is acquainted with stress—some are more familiar than others. In many ways, stress feels like a load you just can’t carry—a feeling you experience when, for example, you have to drive somewhere in a crippling blizzard, when you wake up late the morning of an important job interview, when you run out of money before the next pay period, and before taking an important exam for which, you realize you are not fully prepared.

The Nature and Complexity of Stress: The Good and the Bad

Stress isn’t necessarily bad, even though it’s usually discussed in a negative context. There’s opportunity in stress, and that’s a good thing because it offers potential gain. Athletes and performers use stress positively in “clutch” situations, using it to push themselves to their performance maximums. Even ordinary workers in an organization will use an increased workload and responsibilities as a challenge that increases the quality and quantity of their outputs.

Stress is negative when it’s associated with constraints and demands. Constraints are forces that prevent a person from doing what he or she wants. Demands represent the loss of something desired. They’re the two conditions that are necessary for potential stress to become actual stress. Again, there must be uncertainty over the outcome and the outcome must be important.

Kevin, a student, may feel stress when he is taking a test because he’s facing an opportunity (a passing grade) that includes constraints and demands (in the form of a timed test that features tricky questions). Salomé, a full-time employee, may feel stress when she is confronted with a project because she’s facing an opportunity (a chance to achieve something, make extra money and receive recognition) that includes constraints and demands (long hours, time away from family, a chance that her knowledge and skills aren’t enough to complete the project correctly).

Stressors

For an individual to experience stress, he must first encounter a potential stressor. In general, stressors can be placed into one of two broad categories: chronic and acute. Chronic stressors include events that persist over an extended period of time, such as caring for a parent with dementia, long-term unemployment, or imprisonment. Acute stressors involve brief focal events that sometimes continue to be experienced as overwhelming well after the event has ended, such as falling on an icy sidewalk and breaking your leg (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007). Whether chronic or acute, potential stressors come in many shapes and sizes and can include traumatic events, significant life changes, daily hassles, as well as other situations in which a person is regularly exposed to threat, challenge, or danger.

Traumatic Events

Some stressors involve traumatic events or situations in which a person is exposed to actual or threatened death or serious injury. Stressors in this category include exposure to military combat, threatened or actual physical assaults (e.g., physical attacks, sexual assault, robbery, childhood abuse), terrorist attacks, natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes, floods, hurricanes), and automobile accidents. Men, non-Whites, and individuals in lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups report experiencing a greater number of traumatic events than do women, Whites, and individuals in higher SES groups (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007).

Life Changes

Most stressors that we encounter are not nearly as intense as the ones described above. Many potential stressors we face involve events or situations that require us to make changes in our ongoing lives and require time as we adjust to those changes. Examples include death of a close family member, marriage, divorce, and moving.

In the 1960s, psychiatrists Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe wanted to examine the link between life stressors and physical illness, based on the hypothesis that life events requiring significant changes in a person’s normal life routines are stressful, whether these events are desirable or undesirable. They developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), consisting of 43 life events that require varying degrees of personal readjustment. Many life events that most people would consider pleasant (e.g., holidays, retirement, marriage) are among those listed on the SRRS; these are examples of eustress. Holmes and Rahe also proposed that life events can add up over time, and that experiencing a cluster of stressful events increases one’s risk of developing physical illnesses. Extensive research has demonstrated that accumulating a high number of life change units within a brief period of time (one or two years) is related to a wide range of physical illnesses (even accidents and athletic injuries) and mental health problems (Monat & Lazarus, 1991; Scully, Tosi, & Banning, 2000).

VIEW THIS: Check out the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS). Ask yourself: what stressors would you add to the list (e.g. climate changes, social injustice) to modernize the stressors experiences today?

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) provides researchers a simple, easy-to-administer way of assessing the amount of stress in people’s lives, and it has been used in hundreds of studies. Despite its widespread use, the scale has been subject to criticism. First, many of the items on the SRRS are vague; for example, death of a close friend could involve the death of a long-absent childhood friend that requires little social readjustment. In addition, some have challenged its assumption that undesirable life events are no more stressful than desirable ones. However, most of the available evidence suggests that, at least as far as mental health is concerned, undesirable or negative events are more strongly associated with poor outcomes (such as depression) than are desirable, positive events. Perhaps the most serious criticism is that the scale does not take into consideration respondents’ appraisals of the life events it contains. As you recall, appraisal of a stressor is a key element in the conceptualization and overall experience of stress. Being fired from work may be devastating to some but a welcome opportunity to obtain a better job for others. The SRRS remains one of the most well-known instruments in the study of stress, and it is a useful tool for identifying potential stress-related health outcomes.

Hassles

Potential stressors do not always involve major life events. Daily hassles—the minor irritations and annoyances that are part of our everyday lives (e.g., rush hour traffic, lost keys, obnoxious coworkers, inclement weather, arguments with friends or family)—can build on one another and leave us just as stressed as life change events (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981).

Researchers have demonstrated that the frequency of daily hassles is actually a better predictor of both physical and psychological health than are life change units. In a well-known study of San Francisco residents, the frequency of daily hassles was found to be more strongly associated with physical health problems than were life change events (DeLongis, Coyne, Dakof, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1982). In addition, daily minor hassles, especially interpersonal conflicts, often lead to negative and distressed mood states (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989). Cyber hassles that occur on social media may represent a modern and evolving source of stress. In one investigation, social media stress was tied to loss of sleep in adolescents, presumably because ruminating about social media caused a physiological stress response that increased arousal (van der Schuur, Baumgartner, & Sumter, 2018). Clearly, daily hassles can add up and take a toll on us both emotionally and physically.

Occupation-Related Stressors

Stressors can include situations in which one is frequently exposed to challenging and unpleasant events, such as difficult, demanding, or unsafe working conditions. Although most jobs and occupations can at times be demanding, some are clearly more stressful than others. For example, most people would likely agree that a firefighter’s work is inherently more stressful than that of a florist. Equally likely, most would agree that jobs containing various unpleasant elements, such as those requiring exposure to loud noise (heavy equipment operator), constant harassment and threats of physical violence (prison guard), perpetual frustration (bus driver in a major city), or those mandating that an employee work alternating day and night shifts (hotel desk clerk), are much more demanding—and thus, more stressful—than those that do not contain such elements.

Although the specific stressors for these occupations are diverse, they seem to share some common denominators such as heavy workload and uncertainty about and lack of control over certain aspects of a job. Chronic occupational stress contributes to job strain, a work situation that combines excessive job demands and workload with little discretion in decision making or job control (Karasek & Theorell, 1990). Jobs considered stressful often involve heavy workloads and little job control (e.g., inability to decide when to take breaks). Such jobs are often low-status and include those of factory workers, postal clerks, supermarket cashiers, taxi drivers, and short-order cooks. Job strain can have adverse consequences on both physical and mental health; it has been shown to be associated with increased risk of hypertension (Schnall & Landsbergis, 1994), heart attacks (Theorell et al., 1998), recurrence of heart disease after a first heart attack (Aboa-Éboulé et al., 2007), significant weight loss or gain (Kivimäki et al., 2006), and major depressive disorder (Stansfeld, Shipley, Head, & Fuhrer, 2012). A longitudinal study of over 10,000 British civil servants reported that workers under 50 years old who earlier had reported high job strain were 68% more likely to later develop heart disease than were those workers under 50 years old who reported little job strain (Chandola et al., 2008).

Some people who are exposed to chronically stressful work conditions can experience job burnout, which is a general sense of emotional exhaustion and cynicism in relation to one’s job (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Job burnout occurs frequently among those in human service jobs (e.g., social workers, teachers, therapists, and police officers). Job burnout consists of three dimensions. The first dimension is exhaustion—a sense that one’s emotional resources are drained or that one is at the end of her rope and has nothing more to give at a psychological level. Second, job burnout is characterized by depersonalization: a sense of emotional detachment between the worker and the recipients of his services, often resulting in callous, cynical, or indifferent attitudes toward these individuals. Third, job burnout is characterized by diminished personal accomplishment, which is the tendency to evaluate one’s work negatively by, for example, experiencing dissatisfaction with one’s job-related accomplishments or feeling as though one has categorically failed to influence others’ lives through one’s work.

Caregiver Burnout

Another result of chronic stress and overwork is burnout. The term “burnout” is tossed out by people quite a bit to describe the symptoms of their stress response, but burnout is an authentic condition marked by feelings of exhaustion and powerlessness, leading to apathy, cynicism and complete withdrawal. Burnout is a common condition among those who have chosen careers that serve others or interact heavily with other people—healthcare and teaching among them.

Caregivers care for someone with an illness, injury, or disability. Caregiving can be rewarding, but it can also be challenging. Stress from caregiving is common. Women especially are at risk for the harmful health effects of caregiver stress. These health problems may include depression or anxiety. There are ways to manage caregiver stress. Caregiver burnout is a state of physical, emotional and mental exhaustion. It may be accompanied by a change in attitude, from positive and caring to negative and unconcerned. Burnout can occur when caregivers don’t get the help they need, or if they try to do more than they are able, physically or financially.

Caregivers report much higher levels of stress than people who are not caregivers. Many caregivers are providing help or are “on call” almost all day. Sometimes, this means there is little time for work or other family members or friends. Some caregivers may feel overwhelmed by the amount of care their aging, sick or disabled family member needs.

Although caregiving can be very challenging, it also has its rewards. It feels good to be able to care for a loved one. Spending time together can give new meaning to your relationship.

Your Body’s Response to Stress

The symptoms of stress for a person are as individual as the conditions that cause it. Typically, when presented with stress, the body responds with a surge of hormones and chemicals that results in a fight-or-flight response. As the name would indicate, this response allows you to either fight the stressor or run away from it.

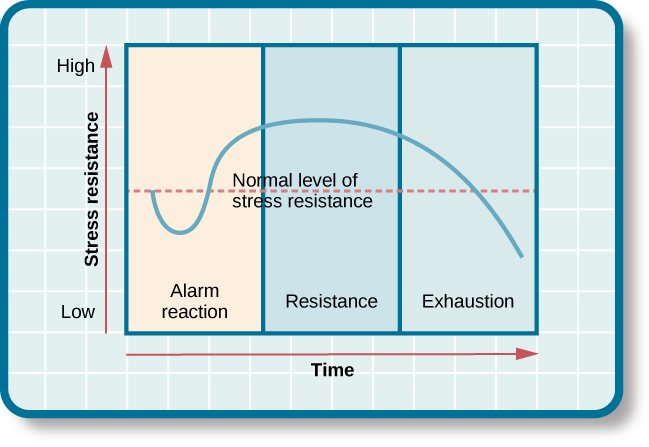

The general adaptation syndrome (GAS) describes the three stages that individuals experience when they encounter stressors, respond and try to adapt:

Alarm. The physical reaction one experiences when a stressor first presents itself. This could include an elevation of blood pressure, dilated pupils, tensing muscles.

Resistance. If the stressor continues to be present, the person fights the threat by preparing to resist, physiologically and psychologically. At first, the stressor will be met with plenty of energy, but if the stressor persists, the individual will start to experience fatigue in fighting it and resistance will wear down.

Exhaustion. Continuous, unsuccessful resistance eventually leads to the collapse of physical and mental defenses.

When stress is chronically present, it begins to do damage to a person’s body and his mental state. High blood pressure, higher risk of heart attack and stroke are just some of the physical ramifications. Anxiety and depression are the hallmarks of psychological symptoms of stress, but can also include cognitive symptoms like forgetfulness and indecisiveness. Behaviorally, a person suffering stress might be prone to sudden verbal outbursts, hostility, drug and alcohol abuse and even violence.

What Does Stress Feel Like?

When we experience excessive stress, either from internal worry or external circumstance, a bodily reaction called the “fight-or-flight” response will be triggered. The response system represents the genetic impulse to protect ourselves from bodily harm. During stress-response processes, the sympathetic nervous system increases heart rate and releases chemicals to prepare the body to either fight or flee. When the fight-or-flight response system get activated, it tends to perceive everything in the environment as a potential threat to survival.

In modern life, we do not get the option of “flight” very often. We have to deal with those stressors all the time and find a solution. When you need to take a final exam, there is no easy way for you to avoid it; sitting in the test room for hours feels like the only choice. Lacking the “flight” option in stress-response process leads to higher stress levels in modern society.

Common Signs and Symptoms of Stress

According to WebMD, recognizing stress symptoms may be harder than you think. You may have any of the following symptoms of stress.

|

Emotional symptoms of stress include: |

Physical symptoms of stress include: |

Cognitive symptoms of stress include: |

Behavioral symptoms of stress include: |

|

Becoming easily agitated, frustrated, and moody Feeling overwhelmed, as if you are losing control or need to take control Having a hard time relaxing and quieting your mind Feeling bad about yourself (low self-esteem), and feeling lonely, worthless, and depressed Avoiding others |

Low energy Headaches Upset stomach, including diarrhea, constipation, and nausea Aches, pains, and tense muscles Chest pain and rapid heartbeat Insomnia Frequent colds and infections Loss of sexual desire and/or ability Nervousness and shaking, ringing in the ears, and cold or sweaty hands and feet Dry mouth and a hard time swallowing |

Constant worrying Racing thoughts Forgetfulness and disorganization Inability to focus Poor judgment Being pessimistic or seeing only the negative side |

Changes in appetite — either not eating or eating too much Procrastinating and avoiding responsibilities More use of alcohol, drugs, or cigarettes Having more nervous behaviors, such as nail biting, fidgeting, and pacing |

The body responds to stress by releasing stress hormones. These hormones make blood pressure, heart rate, and blood sugar levels go up. Long-term stress can help cause a variety of health problems, including:

- Mental health disorders, like depression and anxiety

- Obesity

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Abnormal heart beats

- Menstrual problems

- Acne and other skin problems

WATCH THIS overview video below or online about the impact that stressors have on the body:

Psychophysiological Disorders

If the reactions that compose the stress response are chronic or if they frequently exceed normal ranges, they can lead to cumulative wear and tear on the body, in much the same way that running your air conditioner on full blast all summer will eventually cause wear and tear on it. For example, the high blood pressure that a person under considerable job strain experiences might eventually take a toll on his heart and set the stage for a heart attack or heart failure. Also, someone exposed to high levels of the stress hormone cortisol might become vulnerable to infection or disease because of weakened immune system functioning (McEwen, 1998).

Physical disorders or diseases whose symptoms are brought about or worsened by stress and emotional factors are called psychophysiological disorders. The physical symptoms of psychophysiological disorders are real and they can be produced or exacerbated by psychological factors (hence the psycho and physiological in psychophysiological). A list of frequently encountered psychophysiological disorders is provided in the table below:

|

Types of Psychophysiological Disorders |

|

|

Type of Psychophysiological Disorder |

Examples |

|

Cardiovascular |

hypertension, coronary heart disease |

|

Gastrointestinal |

irritable bowel syndrome |

|

Respiratory |

asthma, allergy |

|

Musculoskeletal |

low back pain, tension headaches |

|

Skin |

acne, eczema, psoriasis |

Before we discuss two kinds of psychophysiological disorders about which a great deal is known: cardiovascular disorders and asthma, it is necessary to turn our attention to a discussion of the immune system—one of the major pathways through which stress and emotional factors can lead to illness and disease.

Stress and the Immune System

In a sense, the immune system is the body’s surveillance system. It consists of a variety of structures, cells, and mechanisms that serve to protect the body from invading microorganisms that can harm or damage the body’s tissues and organs. When the immune system is working as it should, it keeps us healthy and disease free by eliminating harmful bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances that have entered the body (Everly & Lating, 2002).

Immune System Errors

Sometimes, the immune system will function erroneously. For example, sometimes it can go awry by mistaking your body’s own healthy cells for invaders and repeatedly attacking them. When this happens, the person is said to have an autoimmune disease, which can affect almost any part of the body. How an autoimmune disease affects a person depends on what part of the body is targeted. For instance, rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disease that affects the joints, results in joint pain, stiffness, and loss of function. Systemic lupus erythematosus, an autoimmune disease that affects the skin, can result in rashes and swelling of the skin. Grave’s disease, an autoimmune disease that affects the thyroid gland, can result in fatigue, weight gain, and muscle aches (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases [NIAMS], 2012).

In addition, the immune system may sometimes break down and be unable to do its job. This situation is referred to as immunosuppression, the decreased effectiveness of the immune system. When people experience immunosuppression, they become susceptible to any number of infections, illness, and diseases. For example, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a serious and lethal disease that is caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which greatly weakens the immune system by infecting and destroying antibody-producing cells, thus rendering a person vulnerable to any of a number of opportunistic infections (Powell, 1996).

Stressors and Immune Function

The question of whether stress and negative emotional states can influence immune function has captivated researchers for over three decades, and discoveries made over that time have dramatically changed the face of health psychology (Kiecolt-Glaser, 2009). Psychoneuroimmunology is the field that studies how psychological factors such as stress influence the immune system and immune functioning. The term psychoneuroimmunology was first coined in 1981, when it appeared as the title of a book that reviewed available evidence for associations between the brain, endocrine system, and immune system (Zacharie, 2009). To a large extent, this field evolved from the discovery that there is a connection between the central nervous system and the immune system.

Some of the most compelling evidence for a connection between the brain and the immune system comes from studies in which researchers demonstrated that immune responses in animals could be classically conditioned (Everly & Lating, 2002). For example, Ader and Cohen (1975) paired flavored water (the conditioned stimulus) with the presentation of an immunosuppressive drug (the unconditioned stimulus), causing sickness (an unconditioned response). Not surprisingly, rats exposed to this pairing developed a conditioned aversion to the flavored water. However, the taste of the water itself later produced immunosuppression (a conditioned response), indicating that the immune system itself had been conditioned. Many subsequent studies over the years have further demonstrated that immune responses can be classically conditioned in both animals and humans (Ader & Cohen, 2001). Thus, if classical conditioning can alter immunity, other psychological factors should be capable of altering it as well.

Hundreds of studies involving tens of thousands of participants have tested many kinds of brief and chronic stressors and their effect on the immune system (e.g., public speaking, medical school examinations, unemployment, marital discord, divorce, death of spouse, burnout and job strain, caring for a relative with Alzheimer’s disease, and exposure to the harsh climate of Antarctica). It has been repeatedly demonstrated that many kinds of stressors are associated with poor or weakened immune functioning (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004).

When evaluating these findings, it is important to remember that there is a tangible physiological connection between the brain and the immune system. For example, the sympathetic nervous system innervates immune organs such as the thymus, bone marrow, spleen, and even lymph nodes (Maier, Watkins, & Fleshner, 1994). Also, we noted earlier that stress hormones released during hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation can adversely impact immune function. One way they do this is by inhibiting the production of lymphocytes, white blood cells that circulate in the body’s fluids that are important in the immune response (Everly & Lating, 2002).

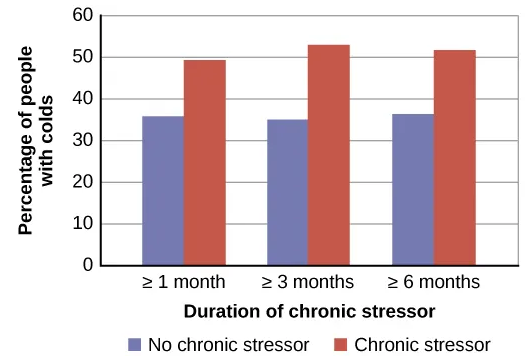

Some of the more dramatic examples demonstrating the link between stress and impaired immune function involve studies in which volunteers were exposed to viruses. The rationale behind this research is that because stress weakens the immune system, people with high stress levels should be more likely to develop an illness compared to those under little stress. In one memorable experiment using this method, researchers interviewed 276 healthy volunteers about recent stressful experiences (Cohen et al., 1998).

Following the interview, these participants were given nasal drops containing the cold virus (in case you are wondering why anybody would ever want to participate in a study in which they are subjected to such treatment, the participants were paid $800 for their trouble). When examined later, participants who reported experiencing chronic stressors for more than one month—especially enduring difficulties involving work or relationships—were considerably more likely to have developed colds than were participants who reported no chronic stressors (Figure Above).

In another study, older volunteers were given an influenza virus vaccination. Compared to controls, those who were caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease (and thus were under chronic stress) showed poorer antibody response following the vaccination (Kiecolt-Glaser, Glaser, Gravenstein, Malarkey, & Sheridan, 1996).

Other studies have demonstrated that stress slows down wound healing by impairing immune responses important to wound repair (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). In one study, for example, skin blisters were induced on the forearm. Subjects who reported higher levels of stress produced lower levels of immune proteins necessary for wound healing (Glaser et al., 1999). Stress, then, is not so much the sword that kills the knight, so to speak; rather, it’s the sword that breaks the knight’s shield, and your immune system is that shield.

Stress and Development

What is the impact of stress on child development? The answer to that question is complex and depends on several factors including the number of stressors, the duration of stress, and the child’s ability to cope with stress.

Children experience different types of stressors that could be manifest in various ways. Normal, everyday stress can provide an opportunity for young children to build coping skills and poses little risk to development. Even long-lasting stressful events, such as changing schools or losing a loved one, can be managed fairly well.

Some experts have theorized that there is a point where prolonged or excessive stress becomes harmful and can lead to serious health effects. When stress builds up in early childhood, neurobiological factors are affected; in turn, levels of the stress hormone cortisol exceed normal ranges. Due in part to the biological consequences of excessive cortisol, children can develop physical, emotional, and social symptoms.

Physical conditions include cardiovascular problems, skin conditions, susceptibility to viruses, headaches, or stomach aches in young children. Emotionally, children may become anxious or depressed, violent, or feel overwhelmed. Socially, they may become withdrawn and act out towards others, or develop new behavioral ticks such as biting nails or picking at skin.

Types of Stress for Children

Researchers have proposed three distinct types of responses to stress in young children: positive, tolerable, and toxic. Positive stress (also called eustress) is necessary and promotes resilience, or the ability to function competently under threat. Such stress arises from brief, mild to moderate stressful experiences, buffered by the presence of a caring adult who can help the child cope with the stressor. This type of stress causes minor, temporary physiological and hormonal changes in the young child such as an increase in heart rate and a change in hormone cortisol levels. The first day of school, a family wedding or making new friends are all examples of positive stressors. Tolerable stress comes from adverse experiences that are more intense in nature but short-lived and can usually be overcome. Some examples of tolerable stressors are family disruptions, accidents or the death of a loved one. The body’s stress response is more intensely activated due to severe stressors; however, the response is still adaptive and temporary.

Toxic stress is a term coined by pediatrician Jack P. Shonkoff of the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University to refer to chronic, excessive stress that exceeds a child’s ability to cope, especially in the absence of supportive caregiving from adults. Extreme, long-lasting stress in the absence of supportive relationships to buffer the effects of a heightened stress response can produce damage and weakening of bodily and brain systems, which can lead to diminished physical and mental health throughout a person’s lifetime. Exposure to such toxic stress can result in the stress response system becoming more highly sensitized to stressful events, producing increased wear and tear on physical systems through over-activation of the body’s stress response. This wear and tear increase the later risk of various physical and mental illnesses.

Prejudice and Discrimination as Toxic Stress

Being the recipient of prejudice and discrimination is associated with a number of negative outcomes. Many studies have shown how perceived discrimination is a significant stressor for marginalized groups (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Discrimination negatively impacts both physical and mental health for individuals in stigmatized groups. As you’ll learn when you study social psychology, various social identities (such as gender, age, religion, sexuality, ethnicity) often lead people to simultaneously be exposed to multiple forms of discrimination, which can have even stronger negative effects on mental and physical health (Vines, Ward, Cordoba, & Black, 2017). For example, the amplified levels of discrimination faced by Latinx transgender women may have related effects, leading to high stress levels and poor mental and physical health outcomes.

Perceived control and the general adaptation syndrome help explain the process by which discrimination affects mental and physical health. Discrimination can be conceptualized as an uncontrollable, persistent, and unpredictable stressor. When a discriminatory event occurs, the target of the event initially experiences an acute stress response (alarm stage). This acute reaction alone does not typically have a great impact on health. However, discrimination tends to be a chronic stressor. As people in marginalized groups experience repeated discrimination, they develop a heightened reactivity as their bodies prepare to act quickly (resistance stage). This long-term accumulation of stress responses can eventually lead to increases in negative emotion and wear on physical health (exhaustion stage). This explains why a history of perceived discrimination is associated with a host of mental and physical health problems including depression, cardiovascular disease, and cancer (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009).

Protecting stigmatized groups from the negative impact of discrimination-induced stress may involve reducing the incidence of discriminatory behaviors in conjunction with protective strategies that reduce the impact of discriminatory events when they occur. Civil rights legislation has protected some stigmatized groups by making discrimination a prosecutable offense in many social contexts. However, some groups (e.g., transgender people) often lack important legal recourse when discrimination occurs. Moreover, most modern discrimination comes in subtle forms that fall below the radar of the law. For example, discrimination may be experienced as selective inhospitality that the target perceives as race-based discrimination, but little is done in response since it would be easy to attribute the behavior to other causes. Although some cultural changes are increasingly helping people to recognize and control subtle discrimination, such shifts may take a long time.

Similar to other stressors, buffers like social support and healthy coping strategies appear to be effective in lowering the impact of perceived discrimination. For example, one study (Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn, & Ismail, 2010) showed that discrimination predicted high psychological distress among African American mothers living in Detroit. However, the women who had readily available emotional support from friends and family experienced less distress than those with fewer social resources. While coping strategies and social support may buffer the effects of discrimination, they fail to erase all of the negative impacts. Vigilant antidiscrimination efforts, including the development of legal protections for vulnerable groups, are needed to reduce discrimination, stress, and the resulting physical and mental health effects.

Consequences of Toxic Stress

Children who experience toxic stress or who live in extremely stressful situations of abuse over long periods of time can suffer long-lasting effects. The structures in the midbrain or limbic system, such as the hippocampus and amygdala, can be vulnerable to prolonged stress. High levels of the stress hormone cortisol can reduce the size of the hippocampus and affect a child’s memory abilities. Stress hormones can also reduce immunity to disease. If the brain is exposed to long periods of severe stress, it can develop a low threshold, making a child hypersensitive to stress in the future.

WATCH THIS short video below or online explaining some of the biological changes that accompany toxic stress:

With chronic toxic stress, children undergo long term hyper-arousal of brain stem activity. This includes an increase in heart rate, blood pressure, and arousal states. These children may experience a change in brain chemistry, which leads to hyperactivity and anxiety. Therefore, it is evident that chronic stress in a young child’s life can create significant physical, emotional, psychological, social and behavioral changes; however, the effects of stress can be minimized if the child has the support of caring adults.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions on how the ‘toxic stress’ of poverty hurts the developing brain:

WATCH THIS video below or online describing a variety of factors involved in the development of resilience:

Trauma in Childhood

Childhood trauma is referred to in academic literature as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Children may go through a range of experiences that classify as psychological trauma, these might include neglect, abandonment, sexual abuse, physical abuse, parent or sibling treated violently, separation or incarceration of parents, or having a parent with a mental illness. These events have profound psychological, physiological, and sociological impacts and can have negative, lasting effects on health and well-being.

Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1998 study on adverse childhood experiences determined that traumatic experiences during childhood are a root cause of many social, emotional, and cognitive impairments that lead to increased risk of unhealthy self-destructive behaviors, risk of violence or re-victimization, chronic health conditions, low life potential, and premature mortality. As the number of adverse experiences increases, the risk of problems from childhood through adulthood also rises. Nearly 30 years of study following the initial study has confirmed this. Many states, health providers, and other groups now routinely screen parents and children for ACEs.

WATCH THIS Ted talk below or online from pediatrician Nadine Burke Harris as she explains the impact of childhood trauma across the lifespan:

Food Insecurity

In 2017 11.8% of households experienced low food security, or food insecurity, at some point during that year. Food insecurity happens when a family has limited or uncertain availability of safe, nutritious food. The most recent statistics suggest that households with children are more at risk for food insecurity, with nearly 18% of children under the age of 18 living in households that have experienced food insecurity within the year. Lack of proper nutrition is a stress on the body in general. Children who are undernourished may have physical developmental delays. Further, food insecurity has been correlated with poor school performance in both reading and math.

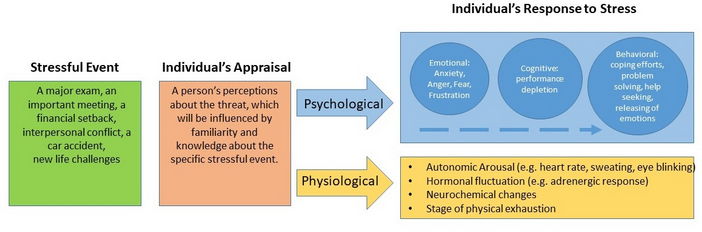

Coping with Stress

To deal with stress in your life, it is important to figure out where that stress originates and notice how you tend to react to it. Later in this chapter, we will show you how community psychologists consider the environment and ecological perspectives as intertwined in stress and coping. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) have been among the most influential psychologists in the stress and coping field, and they defined coping as efforts to manage demands that could exceed our resources. It is important to highlight from this definition that when a person perceives a life circumstance as taxing and exceeding the resources they have; this person will experience stress. Therefore, coping involves your efforts to manage stress, which is illustrated in the figure below.

Coping Defined

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) felt that when humans perceive a life circumstance as taxing and exceeding their resources, stress will be experienced, which we have already defined in the prior section as an overload of incoming information into a system. Therefore, coping involves persons’ efforts to manage stress, whether the process of dealing with stress is adaptive or not (Lazarus, 1993). When we talk about coping, we will need to consider the intensity of the stressor, the context of coping, and an individual’s appraisal of coping expectations.

Coping Types

Research on coping has usually found five types of coping styles (Clarke, 2006; Skinner, et al., 2003; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2005). These include the following: (1) problem-focused coping style involves addressing the problem situation by taking direct acting, planning or thinking of ways to solve the problem, (2) emotion-focused coping style involves expressing feelings or engaging in emotional release activities such as exercising or practicing meditation, (3) seeking-understanding coping style refers to finding understanding of the problem and looking for a meaning of the experience, and (4) seeking help involves using others as a resource to solve the problem. Finally, people might respond to stressors by (5) avoiding the problem and trying to stay away from the problem or potential solution to the problem.

Coping Strategies

Coping strategies are the choices that a person makes in order to respond to a stressor. A strategy can be adaptive (effective) or maladaptive (ineffective or harmful). The ideal adaptive coping strategy varies depending on the context, as well as the personality traits of the person responding. The coping strategies can be problem-solving or active strategies, emotional expression and regulation strategies, seeking understanding strategies, help or support-seeking strategies, and problem avoidance or distraction strategies.

Here is one example of an intervention strategy that shows how to effectively cope with daily and transitional stressors. The strategy is called Shift-and-Persist (Chen & Miller, 2012), and it requires individuals to first shift views of the problem. To shift, you need to (1) recognize and accept the presence of stress, (2) engage in emotional regulation and control negative emotions, and (3) practice self-distancing from the stressor to gain an outsider’s perspective of the stressful context. To persist, you would need to (1) plan for the future through goal setting, (2) recognize a broader perspective when obstacles arise, (3) determine what brings meaning to your life, and (4) become flexible to determine new pathways to goals. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association offer other coping strategies.

WATCH THIS TEDx talk below or online on stress management called How to Humor Your Stress to learn some coping strategies related to shifting perspective:

WATCH THIS TEDx Talk below or online about behavioral coping strategies specific to career burnout stress:

The table below presents a list of coping strategies and is a summary of strategies reported in Clarke, 2006; Skinner, et al., 2003; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2005. Although completed lists are more extensive, this table presents styles reported across the three studies that presented similar types of responses.

|

Coping Strategies: |

Type of Responses: |

|

Problem solving or active strategies |

|

|

Emotional expression and emotional regulation strategies. |

|

|

Seeking understanding strategies. |

|

|

Help seeking strategies and support seeking strategies. |

|

|

Problem avoidance strategies and distraction strategies. |

|

To understand coping as a process, we need to understand people’s reaction to stress in context. This includes assessing whether the coping thoughts or actions are good or bad for that given challenge and given context. In addition, the process of coping includes the particular person, the particular encounters with the stressor, the time of the person’s reactions, and the outcome being examined.

Control and Stress

The desire and ability to predict events, make decisions, and affect outcomes—that is, to enact control in our lives—is a basic tenet of human behavior (Everly & Lating, 2002). Albert Bandura (1997) stated that “the intensity and chronicity of human stress is governed largely by perceived control over the demands of one’s life” (p. 262). As cogently described in his statement, our reaction to potential stressors depends to a large extent on how much control we feel we have over such things. Perceived control is our beliefs about our personal capacity to exert influence over and shape outcomes, and it has major implications for our health and happiness (Infurna & Gerstorf, 2014). Extensive research has demonstrated that perceptions of personal control are associated with a variety of favorable outcomes, such as better physical and mental health and greater psychological well-being (Diehl & Hay, 2010). Greater personal control is also associated with lower reactivity to stressors in daily life. For example, researchers in one investigation found that higher levels of perceived control at one point in time were later associated with lower emotional and physical reactivity to interpersonal stressors (Neupert et al., 2007). Further, a daily diary study with 34 older widows found that their stress and anxiety levels were significantly reduced on days during which the widows felt greater perceived control (Ong et al., 2005).

Learned Helplessness

When we lack a sense of control over the events in our lives, particularly when those events are threatening, harmful, or noxious, the psychological consequences can be profound. In one of the better illustrations of this concept, psychologist Martin Seligman conducted a series of classic experiments in the 1960s in which dogs were placed in a chamber where they received electric shocks from which they could not escape. Later, when these dogs were given the opportunity to escape the shocks by jumping across a partition, most failed to even try; they seemed to just give up and passively accept any shocks the experimenters chose to administer. In comparison, dogs who were previously allowed to escape the shocks tended to jump the partition and escape the pain.

Seligman believed that the dogs who failed to try to escape the later shocks were demonstrating learned helplessness: They had acquired a belief that they were powerless to do anything about the stimulation they were receiving. Seligman also believed that the passivity and lack of initiative these dogs demonstrated was similar to that observed in human depression. Therefore, Seligman speculated that learned helplessness might be an important cause of depression in humans: Humans who experience negative life events that they believe they are unable to control may become helpless. As a result, they give up trying to change the situation and some may become depressed and show lack of initiative in future situations in which they can control the outcomes. In an application Seligman never proposed, learned helplessness was later used as a methodology in the torture of prisoners by U.S. military and intelligence personnel following the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. The psychologists who designed the torture program, James E. Mitchell and Bruce Jesson, theorized that detainees who were subjected to uncontrollable afflictions would eventually become passive and compliant, making them more likely to reveal information to their interrogators. There is little evidence that the program achieved worthwhile results. It is now widely regarded as unethical and unjustified. This example emphasizes the need to consistently consider the ethics of research studies and their applications.

Seligman and colleagues later reformulated the original learned helplessness model of depression. In their reformulation, they emphasized attributions (i.e., a mental explanation for why something occurred) that fostered a sense of learned helplessness. For example, suppose a coworker shows up late to work; your belief as to what caused the coworker’s tardiness would be an attribution (e.g., too much traffic, slept too late, or just doesn’t care about being on time).

The reformulated version of Seligman’s study holds that the attributions made for negative life events contribute to depression. Consider the example of a student who performs poorly on a midterm exam. This model suggests that the student will make three kinds of attributions for this outcome: internal vs. external (believing the outcome was caused by his own personal inadequacies or by environmental factors), stable vs. unstable (believing the cause can be changed or is permanent), and global vs. specific (believing the outcome is a sign of inadequacy in most everything versus just this area). Assume that the student makes an internal (“I’m just not smart”), stable (“Nothing can be done to change the fact that I’m not smart”) and global (“This is another example of how lousy I am at everything”) attribution for the poor performance. The reformulated theory predicts that the student would perceive a lack of control over this stressful event and thus be especially prone to developing depression. Indeed, research has demonstrated that people who have a tendency to make internal, global, and stable attributions for bad outcomes tend to develop symptoms of depression when faced with negative life experiences. Fortunately, attribution habits can be changed through practice. Training in healthy attribution habits has been shown to make people less vulnerable to depression.

Seligman’s learned helplessness model has emerged over the years as a leading theoretical explanation for the onset of major depressive disorder. When you study psychological disorders, you will learn more about the latest reformulation of this model—now called hopelessness theory.

WATCH THIS video below or online with captions of a teacher creating learned helplessness in her students in five minutes:

People who report higher levels of perceived control view their health as controllable, thereby making it more likely that they will better manage their health and engage in behaviors conducive to good health. Not surprisingly, greater perceived control has been linked to lower risk of physical health problems, including declines in physical functioning, heart attacks, and both cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality from cardiac disease. In addition, longitudinal studies of British civil servants have found that those in low-status jobs (e.g., clerical and office support staff) in which the degree of control over the job is minimal are considerably more likely to develop heart disease than those with high-status jobs or considerable control over their jobs.

The link between perceived control and health may provide an explanation for the frequently observed relationship between social class and health outcomes. In general, research has found that more affluent individuals experience better health partly because they tend to believe that they can personally control and manage their reactions to life’s stressors. Perhaps buoyed by the perceived level of control, individuals of higher social class may be prone to overestimating the degree of influence they have over particular outcomes. For example, those of higher social class tend to believe that their votes have greater sway on election outcomes than do those of lower social class, which may explain higher rates of voting in more affluent communities. Other research has found that a sense of perceived control can protect less affluent individuals from poorer health, depression, and reduced life-satisfaction—all of which tend to accompany lower social standing.

Taken together, findings from these and many other studies clearly suggest that perceptions of control and coping abilities are important in managing and coping with the stressors we encounter throughout life.

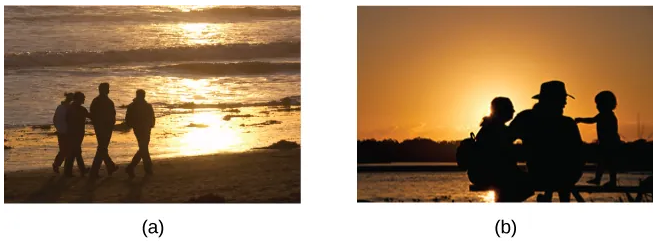

Social Support and Stress Reduction

The need to form and maintain strong, stable relationships with others is a powerful, pervasive, and fundamental human motive (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Building strong interpersonal relationships with others helps us establish a network of close, caring individuals who can provide social support in times of distress, sorrow, and fear.

Social support can be thought of as the soothing impact of friends, family, and acquaintances (Baron & Kerr, 2003). Social support can take many forms, including advice, guidance, encouragement, acceptance, emotional comfort, and tangible assistance (such as financial help). Thus, other people can be very comforting to us when we are faced with a wide range of life stressors, and they can be extremely helpful in our efforts to manage these challenges. Even in nonhuman animals, species mates can offer social support during times of stress. For example, elephants seem to be able to sense when other elephants are stressed and will often comfort them with physical contact—such as a trunk touch—or an empathetic vocal response (Krumboltz, 2014).

Scientific interest in the importance of social support first emerged in the 1970s when health researchers developed an interest in the health consequences of being socially integrated (Stroebe & Stroebe, 1996). Interest was further fueled by longitudinal studies showing that social connectedness reduced mortality. In one classic study, nearly 7,000 Alameda County, California, residents were followed over 9 years. Those who had previously indicated that they lacked social and community ties were more likely to die during the follow-up period than those with more extensive social networks. Compared to those with the most social contacts, isolated men and women were, respectively, 2.3 and 2.8 times more likely to die. These trends persisted even after controlling for a variety of health-related variables, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, self-reported health at the beginning of the study, and physical activity (Berkman & Syme, 1979).

Since the time of that study, social support has emerged as one of the well-documented psychosocial factors affecting health outcomes (Uchino, 2009). A statistical review of 148 studies conducted between 1982 and 2007 involving over 300,000 participants concluded that individuals with stronger social relationships have a 50% greater likelihood of survival compared to those with weak or insufficient social relationships (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). According to the researchers, the magnitude of the effect of social support observed in this study is comparable with quitting smoking and exceeded many well-known risk factors for mortality, such as obesity and physical inactivity.

A number of large-scale studies have found that individuals with low levels of social support are at greater risk of mortality, especially from cardiovascular disorders (Brummett et al., 2001). Further, higher levels of social supported have been linked to better survival rates following breast cancer (Falagas et al., 2007) and infectious diseases, especially HIV infection (Lee & Rotheram-Borus, 2001). In fact, a person with high levels of social support is less likely to contract a common cold. In one study, 334 participants completed questionnaires assessing their sociability; these individuals were subsequently exposed to a virus that causes a common cold and monitored for several weeks to see who became ill. Results showed that increased sociability was linearly associated with a decreased probability of developing a cold (Cohen, Doyle, Turner, Alper, & Skoner, 2003).

For many of us, friends are a vital source of social support. But what if you find yourself in a situation in which you have few friends and companions? Many students who leave home to attend and live at college experience drastic reductions in their social support, which makes them vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and loneliness. Social media can sometimes be useful in navigating these transitions (Raney & Troop Gordon, 2012) but might also cause increases in loneliness (Hunt, Marx, Lipson, & Young, 2018). For this reason, many colleges have designed first-year programs, such as peer mentoring (Raymond & Shepard, 2018), that can help students build new social networks. For some people, our families—especially our parents—are a major source of social support.