9 Module 9: Early Adulthood Development

Module 9 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Explain Emerging Adulthood

Describe Arnett’s concept of emerging adulthood and identify its five key features, such as identity exploration and feeling in-between. - Analyze Developmental Tasks

Summarize the major developmental tasks of early adulthood, including gaining independence, establishing careers, and forming intimate relationships. - Understand Physical Development

Explain physical changes during early adulthood, including peak physical health and the gradual onset of aging. - Examine Healthy Lifestyles

Identify habits that contribute to long-term health and explain their importance in early adulthood. - Discuss Risk Behaviors

Describe the prevalence and impact of risky behaviors in early adulthood, such as substance abuse and unsafe sexual practices. - Understand Cognitive Development

Explain the characteristics of postformal thought, including the ability to think flexibly and integrate opposing viewpoints. - Explore Emotional and Social Development

Summarize Erikson’s stage of intimacy vs. isolation and its relevance to forming close relationships in early adulthood. - Evaluate Friendship and Intimacy

Discuss the role of friendships and romantic relationships in meeting intimacy needs during early adulthood. - Examine Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

Identify the types and signs of IPV and explain strategies for prevention and intervention. - Understand Reproductive Health

Discuss trends in childbearing and common challenges related to fertility in early adulthood. - Analyze International Perspectives

Compare the experience of early adulthood across different cultural and economic contexts, including industrialized and non-industrialized countries. - Understand Education and Career

Explain the relationship between education, career development, and economic stability in early adulthood.

What is Early Adulthood?

Many of the developmental tasks of early adulthood involve becoming part of the adult world and gaining independence. Young adults sometimes complain that they are not treated with respect, especially if they are put in positions of authority over older workers. Consequently, young adults may emphasize their age to gain credibility from those who are even slightly younger. “You’re only 23? I’m 27!” a young adult might exclaim. [Note: This kind of statement is much less likely to come from someone in their 40s!]

The theory of emerging adulthood proposes that a new life stage has arisen between adolescence and young adulthood over the past half-century in industrialized countries.

READ THIS seminal article on the theory of development of emerging adulthood, along with Dr. Arnett’s other research articles on his website.

If the years 18-25 are classified as “young adulthood,” Arnett (from the article above) believes it is then difficult to find an appropriate term for the thirties. Emerging adults are still in the process of obtaining an education, are unmarried, and are childless. By age thirty, most of these individuals do see themselves as adults, based on the belief that they have more fully formed “individualistic qualities of character” such as self-responsibility, financial independence, and independence in decision-making. Arnett suggests that many of the individualistic characteristics associated with adult status correlate to, but are not dependent upon the role responsibilities with a career, marriage, and/or parenthood.

Now, all that has changed. A higher proportion of young people than ever before—about 70% in the United States—pursue education and training beyond secondary school (National Center for Education Statistics, 2012). The early twenties are not a time of entering stable adult work but a time of immense job instability: In the United States, the average number of job changes from ages 20 to 29 is seven. The median age of entering marriage in the United States is now 27 for women and 29 for men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011). Consequently, a new stage of the life span, emerging adulthood, has been created, lasting from the late teens through the mid-twenties, roughly ages 18 to 25.

Five characteristics distinguish emerging adulthood from other life stages (Arnett, 2004). Emerging adulthood is:

- identity exploration,

- instability,

- self-focus,

- feeling in-between adolescence and adulthood,

- a sense of broad possibilities for the future.

Whether or not “emerging adulthood” is considered to be a distinct developmental stage, it can be a useful concept in discussing developmental patterns in early adulthood in our culture today.

WATCH THIS this video clip below or online of Dr. Jeffrey Arnett describing four societal revolutions that may have caused emerging adulthood and how “30 is the new 20,” as twenty-somethings today enjoy unparalleled freedoms when compared with other generations.

Is Emerging Adulthood a Global Phenomenon? International Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

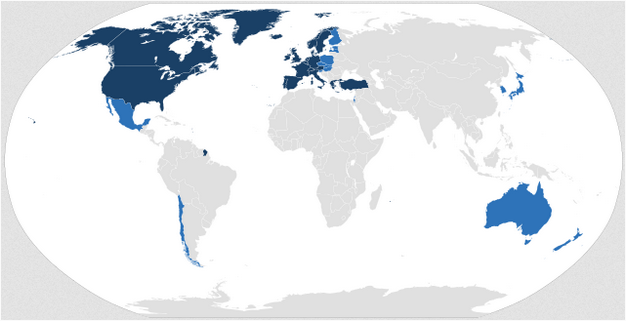

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the non-industrialized countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the industrialized countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called industrialized countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population (UNDP, 2011). The rest of the human population resides in non-industrialized countries, which have much lower median incomes; much lower median educational attainment; and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in OECD countries first, then in non-industrialized countries.

EA in OECD Countries: The Advantages of Affluence

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of participation in postsecondary education as well as median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UN data, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is the longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries (Douglass, 2007). Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world—in fact, in human history (Arnett, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of Asian emerging adults in industrialized countries such as Japan and South Korea are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and in some ways strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around age 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood—for example, free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations. Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents (Phinney & Baldelomar, 2011). For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria (Arnett, 2003; Nelson, Badger, & Wu, 2004). This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, as they pay more heed to their parents’ wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live than emerging adults do in the West (Rosenberger, 2007).

Another notable contrast between Western and Asian emerging adults is in their sexuality. In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three-fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield & Rapson, 2006).

EA in Non-Industrialized Countries: Low But Rising

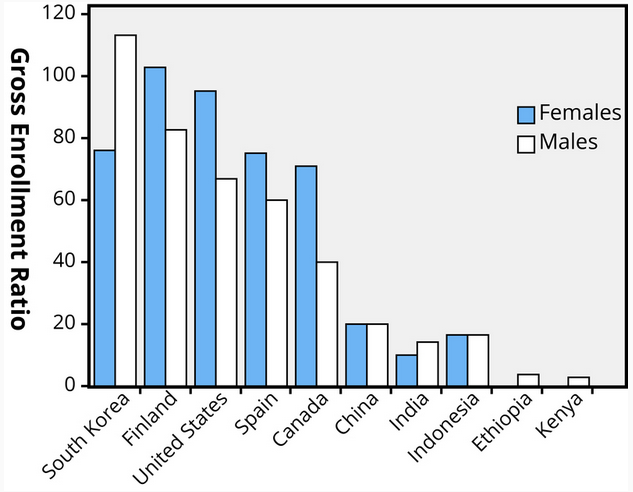

Emerging adulthood is well established as a normative life stage in the industrialized countries described thus far, but it is still growing in non-industrialized countries. Demographically, in non-industrialized countries as in OECD countries, the median ages for entering marriage and parenthood have been rising in recent decades, and an increasing proportion of young people have obtained post-secondary education. Nevertheless, currently, it is only a minority of young people in non-industrialized countries who experience anything resembling emerging adulthood. The majority of the population still marries around age 20 and has long finished education by the late teens. As you can see in the figure below, rates of enrollment in tertiary education are much lower in non-industrialized countries (represented by the five countries on the right) than in OECD countries (represented by the five countries on the left).

For young people in non-industrialized countries, emerging adulthood exists only for the wealthier segment of society, mainly the urban middle class, whereas the rural and urban poor—the majority of the population—have no emerging adulthood and may even have no adolescence because they enter adult-like work at an early age and also begin marriage and parenthood relatively early. What Saraswathi and Larson (2002) observed about adolescence applies to emerging adulthood as well: “In many ways, the lives of middle-class youth in India, South East Asia, and Europe have more in common with each other than they do with those of poor youth in their own countries.” However, as globalization proceeds, and economic development along with it, the proportion of young people who experience emerging adulthood will increase as the middle class expands. By the end of the 21st century, emerging adulthood is likely to be normative worldwide.

Physical Development in Early Adulthood

People in their twenties and thirties are considered young adults. If you are in your early twenties, you are probably at the peak of your physiological development. Your body has completed its growth, though your brain is still developing (as explained in the previous module on adolescence). Physically, you are in the “prime of your life” as your reproductive system, motor ability, strength, and lung capacity are operating at their best. However, these systems will start a slow, gradual decline so that by the time you reach your mid to late 30s, you will begin to notice signs of aging. This includes a decline in your immune system, your response time, and in your ability to recover quickly from physical exertion. For example, you may have noticed that it takes you quite some time to stop panting after running to class or taking the stairs. But, remember that both nature and nurture continue to influence development. Getting out of shape is not an inevitable part of aging; it is probably due to the fact that you have become less physically active and have experienced greater stress. The good news is that there are things you can do to combat many of these changes. So keep in mind, as we continue to discuss the lifespan, that some of the changes we associate with aging can be prevented or turned around if we adopt healthier lifestyles.

In fact, research shows that the habits we establish in our twenties are related to certain health conditions in middle age, particularly the risk of heart disease. What are healthy habits that young adults can establish now that will prove beneficial in later life? Healthy habits include maintaining a lean body mass index, moderate alcohol intake, a smoke-free lifestyle, a healthy diet, and regular physical activity. When experts were asked to name one thing they would recommend young adults do to facilitate good health, their specific responses included: weighing self often, learning to cook, reducing sugar intake, developing an active lifestyle, eating vegetables, practicing portion control, establishing an exercise routine (especially a “post-party” routine, if relevant), and finding a job you love.Being overweight or obese is a real concern in early adulthood. Medical research shows that American men and women with moderate weight gain from early to middle adulthood have significantly increased risks of major chronic disease and mortality (Zheng, et al, 2017). Given the fact that American men and women tend to gain about one to two pounds per year from early to middle adulthood, developing healthy nutrition and exercise habits across adulthood is important (Nichols, 2017).

WATCH THIS video below or online explaining how the brain continues to develop into adulthood:

A Healthy, but Risky Time

Early adulthood tends to be a time of relatively good health. For instance, in the United States, adults ages 18-44 have the lowest percentage of physician office visits than any other age group, younger or older. However, early adulthood seems to be a particularly risky time for violent deaths (rates vary by gender, race, and ethnicity). The leading causes of death for both age groups 15-24 and 25-34 in the U.S. are unintentional injury, suicide, and homicide. Cancer and heart disease follow as the fourth and fifth top causes of death among young adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

Substance Abuse

Rates of violent death are influenced by substance abuse, which peaks during early adulthood. Some young adults use drugs and alcohol as a way of coping with stress from family, personal relationships, or concerns over being on one’s own. Others “use” because they have friends who use and in the early 20s, there is still a good deal of pressure to conform. Youth transitioning into adulthood have some of the highest rates of alcohol and substance abuse. For instance, rates of binge drinking (drinking five or more drinks on a single occasion) in 2014 were: 28.5 percent for people ages 18 to 20 and 43.3 percent for people ages 21-25. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show increases in drug overdose deaths between 2006 and 2016 (with higher rates among males), but with the steepest increases between 2014 and 2016 occurring among males aged 24-34 and females aged 24-34 and 35-44. Rates vary by other factors including race and geography; increased use and abuse of opioids may also play a role.

Drugs impair judgment, reduce inhibitions, and alter mood, all of which can lead to dangerous behavior. Reckless driving, violent altercations, and forced sexual encounters are some examples. College campuses are notorious for binge drinking, which is particularly concerning since alcohol plays a role in over half of all student sexual assaults. Alcohol is involved nearly 90 percent of the time in acquaintance rape (when the perpetrator knows the victim). Over 40 percent of sexual assaults involve alcohol use by the victim and almost 70 percent involve alcohol use by the perpetrator.

Drug and alcohol use increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections because people are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior when under the influence. This includes having sex with someone who has had multiple partners, having anal sex without the use of a condom, having multiple partners, or having sex with someone whose history is unknown. Such risky sexual behavior puts individuals at increased risk for both sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). STDs are especially common among young people. There are about 20 million new cases of STDs each year in the United States and about half of those infections are in people between the ages of 15 and 24. Also, young people are the most likely to be unaware of their HIV infection, with half not knowing they have the virus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

READ THIS article from the University of Rochester Medical Center titled Young Adults Visit Doctors Least at an Age When Risky Behavior Peaks

“”Greater awareness is needed among health care providers and policymakers to improve access to care and ensure that young adults receive appropriate preventive services,” said Fortuna. “During a time when many risks peak and unhealthy lifestyle habits form, routine medical care and preventive counseling can improve both immediate and long-term health.” URMC Communications.

WATCH THIS TED talk below or online about How We Talk About Sexual Assault Online. This video discusses language around sexual assault.

Sex and Fertility in Early Adulthood

Sexual Responsiveness

Men and women tend to reach their peak of sexual responsiveness at different ages. For men, sexual responsiveness tends to peak in the late teens and early twenties. Sexual arousal can easily occur in response to physical stimulation or fantasizing. Sexual responsiveness begins a slow decline in the late twenties and into the thirties although a man may continue to be sexually active throughout adulthood. Over time, a man may require more intense stimulation in order to become aroused. Women often find that they become more sexually responsive throughout their 20s and 30s and may peak in the late 30s or early 40s. This is likely due to greater self-confidence and reduced inhibitions about sexuality.

There are a wide variety of factors that influence sexual relationships during emerging adulthood; this includes beliefs about certain sexual behaviors and marriage. For example, among emerging adults in the United States, it is common for oral sex to not be considered “real sex.. In the 1950s and 1960s, about 75 percent of people between the ages of 20–24 engaged in premarital sex; today, that number is 90 percent. Unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections and diseases (STIs/STDs) are a central issue. As individuals move through emerging adulthood, they are more likely to engage in monogamous sexual relationships and practice safe sex.

Reproduction

For many couples, early adulthood is the time for having children. However, delaying childbearing until the late 20s or early 30s has become more common in the United States. The mean age of first-time mothers in the United States increased 1.4 years, from 24.9 in 2000 to 26.3 in 2014. This shift can primarily be attributed to a larger number of first births to older women along with fewer births to mothers under age 20 (CDC, 2016).

Couples delay childbearing for a number of reasons. Women are now more likely to attend college and begin careers before starting families. And both men and women are delaying marriage until they are in their late 20s and early 30s. In 2018, the average age for a first marriage in the United States was 29.8 for men and 27.8 for women.

Infertility

Infertility affects about 6.7 million women or 11 percent of the reproductive age population (American Society of Reproductive Medicine [ASRM], 2006-2010. Male factors create infertility in about a third of the cases. For men, the most common cause is a lack of sperm production or low sperm production. Female factors cause infertility in another third of cases. For women, one of the most common causes of infertility is ovulation disorder. Other causes of female infertility include blocked fallopian tubes, which can occur when a woman experiences abnormal uterine tissue growth as in endometriosis or resulting from an infection such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

WATCH THIS Watch this video below or online with captions to learn more about the reasons for infertility and the main treatment methods available for conceiving:

Cognition: Beyond Formal Operational, and into Postformal Thought, in Early Adulthood

In the adolescence module, you read about formal operational thought. The hallmark of this type of thinking is the ability to think abstractly or to consider possibilities and ideas about circumstances never directly experienced. Thinking abstractly is only one characteristic of adult thought, however. If you compare a 14-year-old with someone in their late 30s, you would probably find that the later considers not only what is possible, but also what is likely. Why the change? The young adult has gained experience and understands why possibilities do not always become realities. They learn to base decisions on what is realistic and practical, not idealistic, and can make adaptive choices. Adults are also not as influenced by what others think. This advanced type of thinking is referred to as Postformal Thought (Sinnott, 1998).

Dialectical Thought

In addition to moving toward more practical considerations, thinking in early adulthood may also become more flexible and balanced. Abstract ideas that the adolescent believes in firmly may become standards by which the adult evaluates reality. Adolescents tend to think in dichotomies; ideas are true or false; good or bad; right or wrong and there is no middle ground. However, with experience, the adult comes to recognize that there is some right and some wrong in each position, some good or some bad in a policy or approach, some truth and some falsity in a particular idea. This ability to bring together salient aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions is referred to as dialectical thought and is considered one of the most advanced aspects of postformal thinking (Basseches, 1984). Such thinking is more realistic because very few positions, ideas, situations, or people are completely right or wrong. So, for example, parents who were considered angels or devils by the adolescent eventually become just people with strengths and weaknesses, endearing qualities and faults to the adult.

Educational Concerns

In 2005, 37 percent of people in the United States between 18 and 24 had some college or an associate degree; about 30 percent of people between 25 and 34 had completed an education at the bachelor’s level or higher (U. S. Bureau of the Census, 2005). Of current concern is the relationship between higher education and the workplace. Bok (2005), American educator and Harvard University President, calls for a closer alignment between the goals of educators and the demands of the economy. Companies outsource much of their work, not only to save costs, but to find workers with the skills they need.

Colleges and universities, he argues, need to promote global awareness, critical thinking skills, the ability to communicate, moral reasoning, and responsibility in their students (Bok, 2006). Regional accrediting agencies and state organizations provide similar guidelines for educators. Workers need skills in listening, reading, writing, speaking, global awareness, critical thinking, civility, and computer literacy-all skills that enhance success in the workplace. The U. S. Secretary of Education, Margaret Spellings challenges colleges and universities to demonstrate their effectiveness in providing these skills to students and to work toward increasing America’s competitiveness in the global economy (U. S. Department of Education, 2006)

A quality education is more than a credential. Being able to communicate and work well with others is crucial for success. There is some evidence to suggest that most workers who lose their jobs do so because of an inability to work with others, not because they do not know how to do their jobs (Cascio, in Berger 2005). Writing, reading, being able to work with a diverse work team, and having the social skills required to be successful in a career and in society are qualities that go beyond merely earning a credential to compete for a job. Employers must select employees who are not only degreed, but who will be successful in the work environment. Hopefully, students gain these skills as they pursue their degrees.

READ THIS How College Contributes to Workforce Success: Employer Views on What Matters Most report from the American Association of Colleges and Universities looking at what employers want college students to “learn” in order to be prepared for the workforce.

Psychosocial Development

Theories of Early Adult Psychosocial Development

Erikson’s Theory of Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson (1950) believed that the main task of early adulthood is to establish intimate relationships and not feel isolated from others. Intimacy does not necessarily involve romance; it involves caring about another and sharing one’s self without losing one’s self. This developmental crisis of “intimacy versus isolation” is affected by how the adolescent crisis of “identity versus role confusion” was resolved (in addition to how the earlier developmental crises in infancy and childhood were resolved).

The young adult might be afraid to get too close to someone else and lose her or his sense of self, or the young adult might define themselves in terms of another person. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, but there are periods of identity crisis and stability. And, according to Erikson, having some sense of identity is essential for intimate relationships. Although, consider what that would mean for previous generations of women who may have defined themselves through their husbands and marriages, or for Eastern cultures today that value interdependence rather than independence.

Friendships as a source of intimacy

In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners either in marriage or in cohabitation. The kinds of friendships shared by women tend to differ from those shared by men. Friendships between men are more likely to involve sharing information, providing solutions, or focusing on activities rather than discussing problems or emotions. Men tend to discuss opinions or factual information or spend time together in an activity of mutual interest. Friendships between women are more likely to focus on sharing weaknesses, emotions, or problems.

Women talk about difficulties they are having in other relationships and express their sadness, frustrations, and joys. These differences in approaches could lead to problems when men and women come together. She may want to vent about a problem she is having; he may want to provide a solution and move on to some activity. But when he offers a solution, she thinks he does not care! Effective communication is the key to good relationships.

Many argue that other-sex friendships become more difficult for heterosexual men and women because of the unspoken question about whether the friendships will lead to a romantic involvement. Although common during adolescence and early adulthood, these friendships may be considered threatening once a person is in a long-term relationship or marriage. Consequently, friendships may diminish once a person has a partner or single friends may be replaced with couple friends

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious, preventable public health problem that affects millions of Americans. The term “intimate partner violence” describes physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse. This type of violence can occur among heterosexual or same-sex couples and does not require sexual intimacy.

The goal is to stop IPV before it begins. There is a lot to learn about how to prevent IPV. We do know that strategies that promote healthy behaviors in relationships are important. Programs that teach young people skills for dating can prevent violence. These programs can stop violence in dating relationships before it occurs. IPV can vary in frequency and severity. It occurs on a continuum, ranging from one episode that might or might not have lasting impact to chronic and severe episodes over a period of years.

CLICK THIS: IPV is isolating and frightening. Help and support is available. The National Domestic Violence Support Hotline is a place to start.

There are four main types of IPV:

Physical violence is the intentional use of physical force with the potential for causing death, disability, injury, or harm. Physical violence includes, but is not limited to, scratching; pushing; shoving; throwing; grabbing; biting; choking; shaking; aggressive hair pulling; slapping; punching; hitting; burning; use of a weapon; and use of restraints or one’s body, size, or strength against another person. Physical violence also includes coercing other people to commit any of the above acts.

Sexual violence is divided into five categories. Any of these acts constitute sexual violence, whether attempted or completed. Additionally all of these acts occur without the victim’s freely given consent, including cases in which the victim is unable to consent due to being too intoxicated (e.g., incapacitation, lack of consciousness, or lack of awareness) through their voluntary or involuntary use of alcohol or drugs.

Rape or penetration of victim – This includes completed or attempted, forced or alcohol/drug-facilitated unwanted vaginal, oral, or anal insertion. Forced penetration occurs through the perpetrator’s use of physical force against the victim or threats to physically harm the victim.

Victim was made to penetrate someone else – This includes completed or attempted, forced or alcohol/drug-facilitated incidents when the victim was made to sexually penetrate a perpetrator or someone else without the victim’s consent.

Non-physically pressured unwanted penetration – This includes incidents in which the victim was pressured verbally or through intimidation or misuse of authority to consent or acquiesce to being penetrated.

Unwanted sexual contact – This includes intentional touching of the victim or making the victim touch the perpetrator, either directly or through the clothing, on the genitalia, anus, groin, breast, inner thigh, or buttocks without the victim’s consent

Non-contact unwanted sexual experiences – This includes unwanted sexual events that are not of a physical nature that occur without the victim’s consent. Examples include unwanted exposure to sexual situations (e.g., pornography); verbal or behavioral sexual harassment; threats of sexual violence to accomplish some other end; and /or unwanted filming, taking or disseminating photographs of a sexual nature of another person.

Stalking is a pattern of repeated, unwanted, attention and contact that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone else (e.g., family member or friend). Some examples include repeated, unwanted phone calls, emails, or texts; leaving cards, letters, flowers, or other items when the victim does not want them; watching or following from a distance; spying; approaching or showing up in places when the victim does not want to see them; sneaking into the victim’s home or car; damaging the victim’s personal property; harming or threatening the victim’s pet; and making threats to physically harm the victim.

Psychological Aggression is the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to harm another person mentally or emotionally, and/or to exert control over another person. Psychological aggression can include expressive aggression (e.g., name-calling, humiliating); coercive control (e.g., limiting access to transportation, money, friends, and family; excessive monitoring of whereabouts); threats of physical or sexual violence; control of reproductive or sexual health (e.g., refusal to use birth control; coerced pregnancy termination); exploitation of victim’s vulnerability (e.g., immigration status, disability); exploitation of perpetrator’s vulnerability; and presenting false information to the victim with the intent of making them doubt their own memory or perception (e.g., mind games).

How to Navigate Domestic Violence as a Nurse

In many states, nurses are mandatory reporters for domestic violence. As a nurse, it can be important to be able to recognize the signs of intimate partner violence and domestic violence.

While domestic violence affects millions, it is rarely mentioned alongside other public health concerns, such as tobacco and alcohol use.

Chronic domestic violence is associated with several types of chronic illness, like diabetes, depression, digestive diseases, and memory loss.

-Gayle Morris, BSN, MSN (Dec, 2022).

READ THIS: Read Gayle Morris’ article on how to recognize and navigate responding to IPV as a nurse.

Gaining Adult Status

Many of the developmental tasks of early adulthood involve becoming part of the adult world and gaining independence. Young adults sometimes complain that they are not treated with respect, especially if they are put in positions of authority over older workers. Consequently, young adults may emphasize their age to gain credibility from those who are even slightly younger. “You’re only 23? I’m 27!” a young adult might exclaim. [Note: This kind of statement is much less likely to come from someone in their 40s!]

The focus of early adulthood is often on the future. Many aspects of life are on hold while people go to school, go to work, and prepare for a brighter future. There may be a belief that the hurried life now lived will improve ‘as soon as I finish school’ or ‘as soon as I get promoted’ or ‘as soon as the children get a little older.’ As a result, time may seem to pass rather quickly. The day consists of meeting many demands that these tasks bring. The incentive for working so hard is that it will all result in a better future.

References and Resources

Listed below are the references and resources used to curate this module:

Carter, Sarah, et al. (2019). Lifespan Development. Lumen Learning. coures.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/.

Falcone, Kelly (n.d.). Introduction to Health 1e. LibreTexts Medicine. med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Health_and_Fitness/Introduction_to_Health_1e_(Falcone).

Morris, Gayle (Dec. 2022). How to Navigate Domestic Violence as a Nurse. NurseJournal. nursejournal.org/articles/how-to-navigate-domestic-violence-as-a-nurse/.

Owens, R.A. (Sept. 2022). Fostering Professional Identity in Nursing. American Nurse. myamericannurse.com/fostering-professional-identity-in-nursing/.

Roghayeh Jafarianamiri, Seyedeh, et al. (Jun. 2022). Investigating the Professional Identity and Resilience in Nursing Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9277752/.

University of Rochester (Sept. 2009). Young Adults Visit Doctors Least at an Age When Risky Behavior Peaks. University of Rochester Medical Center. urmc.rochester.edu/news/story/young-adults-visit-doctors-least-at-an-age-when-risky-behavior-peaks.