8 Module 8: Adolescent Development

Module 8 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Explain Pubertal Changes

Describe the physical, hormonal, and sexual maturity changes that occur during puberty, including differences between genders. - Understand Brain Development

Explain how brain development during adolescence influences cognitive and emotional behavior, including risk-taking and decision-making. - Discuss Identity Formation

Explore the process of identity formation in adolescence, including Erikson’s stage of identity vs. role confusion and Marcia’s identity statuses. - Analyze Cognitive Development

Describe Piaget’s formal operational thought and its role in abstract, hypothetical, and logical reasoning during adolescence. - Examine Social Relationships

Discuss the changes in peer relationships, family dynamics, and the role of peer pressure during adolescence. - Understand Emotional Challenges

Identify common emotional challenges faced by adolescents, such as anxiety, depression, and the influence of body image. - Explore Gender and Sexual Identity

Explain the development of gender identity, sexual orientation, and how adolescents navigate these aspects of self. - Discuss Health and Nutrition

Describe the importance of proper nutrition, the risks of eating disorders, and the influence of body image on adolescent health. - Analyze Risky Behaviors

Identify the factors contributing to substance use, risky sexual behaviors, and their potential long-term impacts. - Examine Adolescent Sleep Patterns

Explain how changes in circadian rhythms affect sleep patterns and the consequences of sleep deprivation in adolescence. - Understand Moral and Ethical Reasoning

Explore the development of moral reasoning and ethical decision-making during adolescence. - Recognize the Role of Cultural and Environmental Factors

Discuss how cultural, societal, and environmental influences shape the experiences and behaviors of adolescents.

Introduction

Adolescence is a socially constructed concept. In pre-industrial society, children were considered adults when they reached physical maturity; however, today we have an extended time between childhood and adulthood known as adolescence. Adolescence is the period of development that begins at puberty and ends at early adulthood or emerging adulthood; the typical age range is from 12 to 18 years, and this stage of development has some predictable milestones.

Media portrayals of adolescents often seem to emphasize the problems that can be a part of adolescence. Gang violence, school shootings, alcohol-related accidents, drug abuse, and suicides involving teens are all too frequently reflected in newspaper headlines and movie plots. In the professional literature, too, adolescence is frequently portrayed as a negative stage of life—a period of storm and stress to be survived or endured (Arnett, 1999). Adolescents are often characterized as impulsive, reckless and emotionally unstable. This tends to be attributed to “raging hormones” or what is now known as the “teen brain.”

With all of the attention given to negative images of adolescents, the positive aspects of adolescence can be overlooked (APA, 2000). Most adolescents in fact succeed in school, are attached to their families and their communities, and emerge from their teen years without experiencing serious problems such as substance abuse or involvement with violence. Recent research suggests that it may be time to lay the stereotype of the “wild teenage brain” to rest. This research posits that brain deficits do not make teens do risky things; lack of experience and a drive to explore the world are the real factors. Evidence supports that risky behavior during adolescence is a normal part of development and reflects a biologically driven need for exploration – a process aimed at acquiring experience and preparing teens for the complex decisions they will need to make as adults (Romer, Reyna, & Satterthwaite, 2017). Furthermore, McNeely & Blanchard (2009) described the adolescent years as a “time of opportunity, not turmoil.”

Second only to infant development, adolescents experience rapid development in a short period of time. During adolescence, children gain 50% of their adult body weight, experience puberty and become capable of reproducing, and experience an astounding transformation in their brains. All of these changes occur in the context of rapidly expanding social spheres. Adolescents begin to learn about adult responsibilities and adult relationships. The details of growing bodies and the rational and irrational thinking of adolescents are covered in this module. As you will learn, although the physical development of adolescents is often completed by age 18, the brain requires many more years to reach maturity. Understanding these changes developmentally can help both adults and adolescents enjoy this second decade of life.

This module will outline changes that occur during adolescence in three domains: physical, cognitive, and psychosocial. Physical changes associated with puberty are triggered by hormones. Cognitive changes include improvements in complex and abstract thought, as well as development that happens at different rates in distinct parts of the brain and increases adolescents’ propensity for risky behavior because increases in sensation-seeking and reward motivation precede increases in cognitive control. Within the psychosocial domain, changes in relationships with parents, peers, and romantic partners will be considered. Adolescents’ relationships with parents go through a period of redefinition in which adolescents become more autonomous, and aspects of parenting, such as distal monitoring and psychological control, become more salient. Peer relationships are important sources of support and companionship during adolescence yet can also promote problem behaviors. Same-sex peer groups evolve into mixed-sex peer groups, and adolescents’ romantic relationships tend to emerge from these groups. Identity formation occurs as adolescents explore and commit to different roles and ideological positions.

No adolescent can truly be understood in separate parts—an adolescent is a “package deal.” Change in one area of development typically leads to, or occurs in conjunction with, changes in other areas. Furthermore, no adolescent can be fully understood outside the context of their family, neighborhood, school, workplace, or community or without considering such factors as gender, race, sexual orientation, disability or chronic illness, and religious beliefs (APA, 2002).

Physical Development

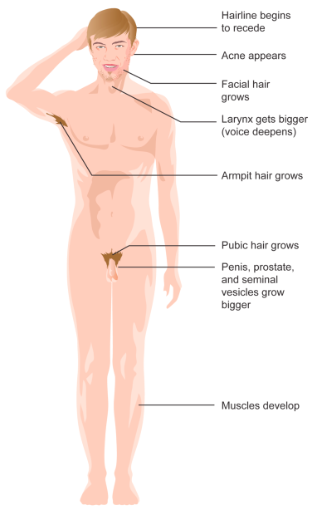

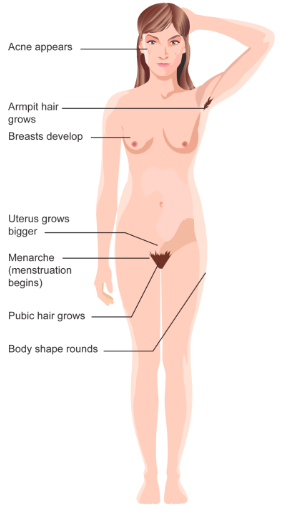

Physical changes of puberty mark the onset of adolescence (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). For both boys and girls, these changes include a growth spurt in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes (e.g., pimples). Boys also experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voice. Girls experience breast development and begin menstruating. These pubertal changes are driven by hormones, particularly an increase in testosterone for boys and estrogen for girls. The physical changes that occur during adolescence are greater than those of any other time of life, with the exception of infancy. In some ways, however, the changes in adolescence are more dramatic than those that occur in infancy—unlike infants, adolescents are aware of the changes that are taking place and of what the changes mean. In this section, you will learn about the pubertal changes in body size, proportions, and sexual maturity, the social and emotional attitudes and reactions toward puberty, and some of the health concerns during adolescence, including eating disorders.

Puberty Begins

Puberty is the period of rapid growth and sexual development that begins in adolescence and starts at some point between ages 8 and 14. While the sequence of physical changes in puberty is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary widely. Every person’s individual timetable for puberty is different and is primarily influenced by heredity; however environmental factors—such as diet and exercise—also exert some influence.

Adolescence has evolved historically, with evidence indicating that this stage is lengthening as individuals start puberty earlier and transition to adulthood later than in the past. Puberty today begins, on average, at age 10–11 years for girls and 11–12 years for boys. This average age of onset has decreased gradually over time since the 19th century by 3–4 months per decade, which has been attributed to a range of factors including better nutrition, obesity, increased father absence, and other environmental factors (Steinberg, 2013). Completion of formal education, financial independence from parents, marriage, and parenthood have all been markers of the end of adolescence and beginning of adulthood, and all of these transitions happen, on average, later now than in the past. In fact, the prolonging of adolescence has prompted the introduction of a new developmental period called emerging adulthood that captures these developmental changes out of adolescence and into adulthood, occurring from approximately ages 18 to 29 (Arnett, 2000). We’ll learn more about this phase in the next module on early adulthood.

Hormonal Changes

Puberty involves distinctive physiological changes in an individual’s height, weight, body composition, and circulatory and respiratory systems, and during this time, both the adrenal glands and sex glands mature. These changes are largely influenced by hormonal activity. Many hormones contribute to the beginning of puberty, but most notably a major rush of estrogen for girls and testosterone for boys. Hormones play an organizational role (priming the body to behave in a certain way once puberty begins) and an activational role (triggering certain behavioral and physical changes). During puberty, the adolescent’s hormonal balance shifts strongly towards an adult state; the process is triggered by the pituitary gland, which secretes a surge of hormonal agents into the blood stream and initiates a chain reaction.

Puberty occurs over two distinct phases, and the first phase, adrenarche, begins at 6 to 8 years of age and involves increased production of adrenal androgens that contribute to a number of pubertal changes—such as skeletal growth. The second phase of puberty, gonadarche, begins several years later and involves increased production of hormones governing physical and sexual maturation.

Sexual Maturation

During puberty, primary and secondary sex characteristics develop and mature. Primary sex characteristics are organs specifically needed for reproduction—the uterus and ovaries in females and testes in males. Secondary sex characteristics are physical signs of sexual maturation that do not directly involve sex organs, such as development of breasts and hips in girls, and development of facial hair, increased muscle and bone mass, and a deepened voice in boys. Both sexes experience development of pubic and underarm hair, as well as increased development of sweat glands.

The male and female gonads are activated by the surge of the hormones discussed earlier, which puts them into a state of rapid growth and development. The testes primarily release testosterone and the ovaries release estrogen; the production of these hormones increases gradually until sexual maturation is met.

For girls, observable changes begin with nipple growth and pubic hair. Then the body increases in height while fat forms particularly on the breasts and hips. The first menstrual period (menarche) is followed by more growth, which is usually completed by four years after the first menstrual period began. Girls experience menarche usually around 12–13 years old. For boys, the usual sequence is growth of the testes, initial pubic-hair growth, growth of the penis, first ejaculation of seminal fluid (spermarche), appearance of facial hair, a peak growth spurt, deepening of the voice, and final pubic-hair growth. (Herman-Giddens et al, 2012). Boys experience spermarche, the first ejaculation, around 13–14 years old.

Physical Growth: The Growth Spurt

During puberty, both sexes experience a rapid increase in height and weight (referred to as a growth spurt) over about 2-3 years resulting from the simultaneous release of growth hormones, thyroid hormones, and androgens. Males experience their growth spurt about two years later than females. For girls the growth spurt begins between 8 and 13 years old (average 10-11), with adult height reached between 10 and 16 years old. Boys begin their growth spurt slightly later, usually between 10 and 16 years old (average 12-13), and reach their adult height between 13 and 17 years old. Both nature (i.e., genes) and nurture (e.g., nutrition, medications, and medical conditions) can influence both height and weight.

Before puberty, there are nearly no differences between males and females in the distribution of fat and muscle. During puberty, males grow muscle much faster than females, and females experience a higher increase in body fat and bones become harder and more brittle. An adolescent’s heart and lungs increase in both size and capacity during puberty; these changes contribute to increased strength and tolerance for exercise.

WATCH THIS video below or online to see a summary of the main biological changes that occur during puberty. You can view the transcript for “Physical development in adolescence | Behavior | MCAT | Khan Academy” here.

Reactions Toward Puberty and Physical Development

The accelerated growth in different body parts happens at different times, but for all adolescents it has a fairly regular sequence. The first places to grow are the extremities (head, hands, and feet), followed by the arms and legs, and later the torso and shoulders. This non-uniform growth is one reason why an adolescent body may seem out of proportion. Additionally, because rates of physical development vary widely among teenagers, puberty can be a source of pride or embarrassment.

Most adolescents want nothing more than to fit in and not be distinguished from their peers in any way, shape or form (Mendle, 2015). So when a child develops earlier or later than their peers, there can be long-lasting effects on mental health. Simply put, beginning puberty earlier than peers presents great challenges, particularly for girls. The picture for early-developing boys isn’t as clear, but evidence suggests that they, too, eventually might suffer ill effects from maturing ahead of their peers. The biggest challenges for boys, however, seem to be more related to late development.

As mentioned in the Khan Academy video about physical development, early maturing boys tend to be stronger, taller, and more athletic than their later maturing peers. They are usually more popular, confident, and independent, but they are also at a greater risk for substance abuse and early sexual activity (Flannery, Rowe, & Gulley, 1993; Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpela, Rissanen, & Rantanen, 2001). Additionally, more recent research found that while early-maturing boys initially had lower levels of depression than later-maturing boys, over time they showed signs of increased anxiety, negative self-image and interpersonal stress. (Rudolph, Troop-Gordon, Lambert, & Natsuaki, 2014).

Early maturing girls may be teased or overtly admired, which can cause them to feel self-conscious about their developing bodies. These girls are at increased risk of a range of psychosocial problems including depression, substance use and early sexual behavior (Graber, 2013). These girls are also at a higher risk for eating disorders, which we will discuss in more detail later in this module (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001; Graber, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Striegel-Moore & Cachelin, 1999).

Late blooming boys and girls (i.e., they develop more slowly than their peers) may feel self-conscious about their lack of physical development. Negative feelings are particularly a problem for late maturing boys, who are at a higher risk for depression and conflict with parents (Graber et al., 1997) and more likely to be bullied (Pollack & Shuster, 2000).

Health During Adolescence

Nutrition

Adequate adolescent nutrition is necessary for optimal growth and development. Dietary choices and habits established during adolescence greatly influence future health, yet many studies report that teens consume few fruits and vegetables and are not receiving the calcium, iron, vitamins, or minerals necessary for healthy development.

One of the reasons for poor nutrition is anxiety about body image, which is a person’s idea of how their body looks. The way adolescents feel about their bodies can affect the way they feel about themselves as a whole. Few adolescents welcome their sudden weight increase, so they may adjust their eating habits to lose weight. Adding to the rapid physical changes, they are simultaneously bombarded by messages, and sometimes teasing, related to body image, appearance, attractiveness, weight, and eating that they encounter in the media, at home, and from their friends/peers (both in person and via social media).

Much research has been conducted on the psychological ramifications of body image on adolescents. Modern day teenagers are exposed to more media on a daily basis than any generation before them. Recent studies have indicated that the average teenager watches roughly 1500 hours of television per year, and 70% use social media multiple times a day. As such, modern day adolescents are exposed to many representations of ideal, societal beauty. The concept of a person being unhappy with their own image or appearance has been defined as “body dissatisfaction.” In teenagers, body dissatisfaction is often associated with body mass, low self-esteem, and atypical eating patterns. Scholars continue to debate the effects of media on body dissatisfaction in teens. What we do know is that two-thirds of U.S. high school girls are trying to lose weight and one-third think they are overweight, while only one-sixth are actually overweight (MMWR, June 10, 2016).

Eating Disorders

Dissatisfaction with body image can explain why many teens, mostly girls, eat erratically or ingest diet pills to lose weight and why boys may take steroids to increase their muscle mass. Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2019). Eating disorders affect both genders, although rates among women are 2½ times greater than among men. Similar to women who have eating disorders, some men also have a distorted sense of body image, including muscle dysmorphia or an extreme concern with becoming more muscular.

Because of the high mortality rate, researchers are looking into the etiology of the disorder and associated risk factors. Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (NIMH, 2019). Eating disorders appear to run in families, and researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Researchers have also found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with healthy women. The main criteria for the most common eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Health Consequences of Eating Disorders

For those suffering from anorexia, health consequences include an abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure, which increase the risk for heart failure. Additionally, there is a reduction in bone density (osteoporosis), muscle loss and weakness, severe dehydration, fainting, fatigue, and overall weakness. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder. Individuals with this disorder may die from complications associated with starvation, while others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders.

The binging and purging cycle of bulimia can affect the digestive system and lead to electrolyte and chemical imbalances that can affect the heart and other major organs. Frequent vomiting can cause inflammation and possible rupture of the esophagus, as well as tooth decay and staining from stomach acids. Lastly, binge eating disorder results in similar health risks to obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol level, heart disease, Type II diabetes, and gall bladder disease (National Eating Disorders Association, 2016).

Eating Disorders Treatment

To treat eating disorders, getting adequate nutrition and stopping inappropriate behaviors, such as purging, are the foundations of treatment. Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and include medical care, nutritional counseling, medications (such as antidepressants), and individual, group, and/or family psychotherapy (NIMH, 2019). For example, the Maudsley Approach has parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa be actively involved their child’s treatment, such as assuming responsibility for feeding their child. To eliminate binge eating and purging behaviors, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) assists sufferers by identifying distorted thinking patterns and changing inaccurate beliefs.

VISIT THIS Visit National Eating Disorders Association to learn more about eating disorders and get help and resources if you or someone you know struggles with one.

Brain Development During Adolescence

The Teen Brain: Six Things to Know

As you learn about brain development during adolescence, consider these six facts from The National Institute of Mental Health:

1. Your brain does not keep getting bigger as you get older

For girls, the brain reaches its largest physical size around 11 years old and for boys, the brain reaches its largest physical size around age 14. Of course, this difference in age does not mean either boys or girls are smarter than one another!

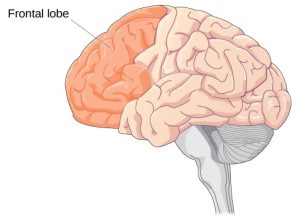

2. But that doesn’t mean your brain is done maturing

For both boys and girls, although your brain may be as large as it will ever be, your brain doesn’t finish developing and maturing until your mid- to late-20s. The front part of the brain, called the prefrontal cortex, is one of the last brain regions to mature. It is the area responsible for planning, prioritizing and controlling impulses.

3. The teen brain is ready to learn and adapt

In a digital world that is constantly changing, the adolescent brain is well prepared to adapt to new technology—and is shaped in return by experience.

4. Many mental disorders appear during adolescence

All the big changes the brain is experiencing may explain why adolescence is the time when many mental disorders—such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders—emerge.

5. The teen brain is resilient

Although adolescence is a vulnerable time for the brain and for teenagers in general, most teens go on to become healthy adults. Some changes in the brain during this important phase of development actually may help protect against long-term mental disorders.

6. Teens need more sleep than children and adults

Although it may seem like teens are lazy, science shows that melatonin levels (or the “sleep hormone” levels) in the blood naturally rise later at night and fall later in the morning than in most children and adults. This may explain why many teens stay up late and struggle with getting up in the morning. Teens should get about 9-10 hours of sleep a night, but most teens don’t get enough sleep. A lack of sleep makes paying attention hard, increases impulsivity and may also increase irritability and depression.

The human brain is not fully developed by the time a person reaches puberty. Between the ages of 10 and 25, the brain undergoes changes that have important implications for behavior. The brain reaches 90% of its adult size by the time a person is six or seven years of age. Thus, the brain does not grow in size much during adolescence. However, the creases in the brain continue to become more complex until the late teens. The biggest changes in the folds of the brain during this time occur in the parts of the cortex that process cognitive and emotional information.

Up until puberty, brain cells continue to bloom in the frontal region. Some of the most developmentally significant changes in the brain occur in the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in decision making and cognitive control, as well as other higher cognitive functions. During adolescence, myelination and synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex increases, improving the efficiency of information processing, and neural connections between the prefrontal cortex and other regions of the brain are strengthened. However, this growth takes time and the growth is uneven.

The limbic system develops years ahead of the prefrontal cortex. Development in the limbic system plays an important role in determining rewards and punishments and processing emotional experience and social information. Pubertal hormones target the amygdala directly and powerful sensations become compelling (Romeo, 2013). Brain scans confirm that cognitive control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement (Hartley & Somerville, 2015). Recall that this area is responsible for judgment, impulse control, and planning, and it is still maturing into early adulthood (Casey, Tottenham, Liston, & Durston, 2005).

Additionally, changes in both the levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin in the limbic system make adolescents more emotional and more responsive to rewards and stress. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter in the brain associated with pleasure and attuning to the environment during decision-making. During adolescence, dopamine levels in the limbic system increase and input of dopamine to the prefrontal cortex increases. The increased dopamine activity in adolescence may have implications for adolescent risk-taking and vulnerability to boredom. Serotonin is involved in the regulation of mood and behavior. It affects the brain in a different way. Known as the “calming chemical,” serotonin eases tension and stress. Serotonin also puts a brake on the excitement and sometimes recklessness that dopamine can produce. If there is a defect in the serotonin processing in the brain, impulsive or violent behavior can result.

When the overall brain chemical system is working well, it seems that these chemicals interact to balance out extreme behaviors. But when stress, arousal or sensations become extreme, the adolescent brain is flooded with impulses that overwhelm the prefrontal cortex, and as a result, adolescents engage in increased risk-taking behaviors and emotional outbursts possibly because the frontal lobes of their brains are still developing.

Later in adolescence, the brain’s cognitive control centers in the prefrontal cortex develop, increasing adolescents’ self-regulation and future orientation. The difference in timing of the development of these different regions of the brain contributes to more risk taking during middle adolescence because adolescents are motivated to seek thrills that sometimes come from risky behavior, such as reckless driving, smoking, or drinking, and have not yet developed the cognitive control to resist impulses or focus equally on the potential risks (Steinberg, 2008). One of the world’s leading experts on adolescent development, Laurence Steinberg, likens this to engaging a powerful engine before the braking system is in place. The result is that adolescents are more prone to risky behaviors than are children or adults.

WATCH THIS video below or online for further explanation and highlights of the key developments in the brain during adolescence. You can view the transcript for “Brain changes during adolescence | Behavior | MCAT | Khan Academy” here.

As mentioned in the introduction to adolescence, too many who have read the research on the teenage brain come to quick conclusions about adolescents as irrational loose cannons. However, adolescents are actually making choices influenced by a very different set of chemical influences than their adult counterparts—a hopped up reward system that can drown out warning signals about risk. Adolescent decisions are not always defined by impulsivity because of lack of brakes, but because of planned and enjoyable pressure to the accelerator. It is helpful to put all of these brain processes in developmental context. Young people need to somewhat enjoy the thrill of risk taking in order to complete the incredibly overwhelming task of growing up.

WATCH THIS video below or online to learn more about research related to brain changes and behavior during adolescence. You can view the transcript for “The Teenage Brain Explained” here.

Sleep

Brain development even affects the way teens sleep. Adolescents’ normal sleep patterns are different from those of children and adults. Teens are often drowsy upon waking, tired during the day, and wakeful at night. See the sixth fact in “The Teen Brain” section above for more details.

According to the National Sleep Foundation (NSF) (2016), adolescents need about 8 to 10 hours of sleep each night to function best. The most recent Sleep in America poll in 2006 indicated that adolescents between sixth and twelfth grade were not getting the recommended amount of sleep. On average adolescents only received 7 1⁄2 hours of sleep per night on school nights with younger adolescents getting more than older ones (8.4 hours for sixth graders and only 6.9 hours for those in twelfth grade). For the older adolescents, only about one in ten (9%) get an optimal amount of sleep, and they are more likely to experience negative consequences the following day. These include feeling too tired or sleepy, being cranky or irritable, falling asleep in school, having a depressed mood, and drinking caffeinated beverages (NSF, 2016). Additionally, they are at risk for substance abuse, car crashes, poor academic performance, obesity, and a weakened immune system (Weintraub, 2016).

Why don’t adolescents get adequate sleep? In addition to known environmental and social factors, including work, homework, media, technology, and socializing, the adolescent brain is also a factor. As adolescent go through puberty, their circadian rhythms change and push back their sleep time until later in the evening (Weintraub, 2016). This biological change not only keeps adolescents awake at night, it makes it difficult for them to get up in the morning. When they are awake too early, their brains do not function optimally. Impairments are noted in attention, behavior, and academic achievement, while increases in tardiness and absenteeism are also demonstrated.

To support adolescents’ later sleeping schedule, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that school not begin any earlier than 8:30 a.m. Unfortunately, over 80% of American schools begin their day earlier than 8:30 a.m. with an average start time of 8:03 a.m. (Weintraub, 2016). Psychologists and other professionals have been advocating for later school times, and they have produced research demonstrating better student outcomes for later start times. More middle and high schools have changed their start times to better reflect the sleep research. However, the logistics of changing start times and bus schedules are proving too difficult for some schools leaving many adolescent vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep deprivation.

REVIEW THIS As research reveals the importance of sleep for teenagers, many people advocate for later high school start times. Read about some of the research at the National Sleep Foundation on school start times or watch this TED talk by Wendy Troxel: “Why Schools Should Start Later for Teens”.

Sexual Development

Developing sexually is an expected and natural part of growing into adulthood. Healthy sexual development involves more than sexual behavior. It is the combination of physical sexual maturation (puberty, age-appropriate sexual behaviors), the formation of a positive sexual identity, and a sense of sexual well-being (discussed more in depth later in this module). During adolescence, teens strive to become comfortable with their changing bodies and to make healthy, safe decisions about which sexual activities, if any, they wish to engage in.

Earlier in the physical development section, we discussed primary and secondary sex characteristics. During puberty, every primary sex organ (the ovaries, uterus, penis, and testes) increases dramatically in size and matures in function. During puberty, reproduction becomes possible. Simultaneously, secondary sex characteristics develop. These characteristics are not required for reproduction, but they do signify masculinity and femininity. At birth, boys and girls have similar body shapes, but during puberty, males widen at the shoulders and females widen at the hips and develop breasts (examples of secondary sex characteristics). Sexual development is impacted by a dynamic mixture of physical and cognitive change coupled with social expectations. With physical maturation, adolescents may become alternately fascinated with and chagrined by their changing bodies, and often compare themselves to the development they notice in their peers or see in the media. For example, many adolescent girls focus on their breast development, hoping their breasts will conform to an ideal body image.

As the sex hormones cause biological changes, they also affect the brain and trigger sexual thoughts. Culture, however, shapes actual sexual behaviors. Emotions regarding sexual experience, like the rest of puberty, are strongly influenced by cultural norms regarding what is expected at what age, with peers being the most influential. Simply put, the most important influence on adolescents’ sexual activity is not their bodies, but their close friends, who have more influence than do sex or ethnic group norms (van de Bongardt et al., 2015).

Sexual interest and interaction are a natural part of adolescence. Sexual fantasy and masturbation episodes increase between the ages of 10 and 13. Masturbation is very ordinary—even young children have been known to engage in this behavior. As the bodies of children mature, powerful sexual feelings begin to develop, and masturbation helps release sexual tension. For adolescents, masturbation is a common way to explore their erotic potential, and this behavior can continue throughout adult life.

Sexual Interactions

Many early social interactions tend to be nonsexual—text messaging, phone calls, email—but by the age of 12 or 13, some young people may pair off and begin dating and experimenting with kissing, touching, and other physical contact, such as oral sex. The vast majority of young adolescents are not prepared emotionally or physically for oral sex and sexual intercourse. If adolescents this young do have sex, they are highly vulnerable for sexual and emotional abuse, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, and early pregnancy. For STIs in particular, adolescents are slower to recognize symptoms, tell partners, and get medical treatment, which puts them at risk of infertility and even death.

VISIT THIS Visit the CDC website to learn more about sexual behavior in adolescence.

Adolescents ages 14 to 16 understand the consequences of unprotected sex and teen parenthood, if properly taught, but cognitively they may lack the skills to integrate this knowledge into everyday situations or consistently to act responsibly in the heat of the moment. By the age of 17, many adolescents have willingly experienced sexual intercourse. Teens who have early sexual intercourse report strong peer pressure as a reason behind their decision. Some adolescents are just curious about sex and want to experience it.

Becoming a sexually healthy adult is a developmental task of adolescence that requires integrating psychological, physical, cultural, spiritual, societal, and educational factors. It is particularly important to understand the adolescent in terms of their physical, emotional, and cognitive stage. Additionally, healthy adult relationships are more likely to develop when adolescent impulses are not shamed or feared. Guidance is certainly needed, but acknowledging that adolescent sexuality development is both normal and positive would allow for more open communication so adolescents can be more receptive to education concerning the risks (Tolman & McClelland, 2011).

Adolescents are receptive to their culture, to the models they see at home, in school, and in the mass media. These observations influence moral reasoning and moral behavior, which we discuss in more detail later in this module. Decisions regarding sexual behavior are influenced by teens’ ability to think and reason, their values, and their educational experience. Helping adolescents recognize all aspects of sexual development encourages them to make informed and healthy decisions about sexual matters.

Drug Use and Abuse

Drug use is, in part, the result of socialization. Adolescents may try drugs when their friends convince them to, and these decisions are based on social norms about the risks and benefits of various drugs. Although young people have experimented with cigarettes, alcohol, and other drugs for many generations, it would be better if they did not. All recreational drug use is associated with at least some risks, and those who begin using drugs earlier are also more likely to use more dangerous drugs. They may develop an addiction or substance abuse problem later on. Additionally, Dr. Mark Willenbring of the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism describes addiction as “a disorder of young people” (2007). He believes that approximately 75% of addiction develops by the age of 25, which roughly corresponds to the age when the pre-frontal cortex in a person’s brain finishes forming. The brain maturation occurring during these years means drug use during adolescence has wider and longer-lasting negative consequences than use during other life stages.

If addiction begins in adolescence, we must question, why that is the case? The answer is that this is the age when our brains are most vulnerable to the effects of drugs, while we are also our most curious and risk-taking selves. The perceived danger of trying drugs is lowest among high school students, and their desire to try novel things is at its peak.

Adolescents experiment with drugs or continue taking them for several reasons, including:

- To fit in: Many teens use drugs “because others are doing it”—or they think others are doing it—and they fear not being accepted in a social circle that includes drug-using peers.

- To feel good: Drugs of abuse interact with the neurochemistry of the brain to produce feelings of pleasure. The intensity of this euphoria differs by the type of drug and how it is used.

- To feel better: Some adolescents suffer from depression, social anxiety, stress-related disorders, and physical pain. Using drugs may be an attempt to lessen these feelings of distress. Stress especially plays a significant role in starting and continuing drug use as well as returning to drug use (relapsing) for those recovering from an addiction.

- To do better: Ours is a very competitive society, in which the pressure to perform athletically and academically can be intense. Some adolescents may turn to certain drugs like illegal or prescription stimulants because they think those substances will enhance or improve their performance.

- To experiment: Adolescents are often motivated to seek new experiences, particularly those they perceive as thrilling or daring.

Rates of substance use

The Monitoring the Future survey is given annually to students in eighth, 10th, and 12th grades who self-report their substance use behaviors over various time periods, such as past 30 days, past 12 months, and lifetime. The survey also documents students’ perception of harm, disapproval of use, and perceived availability of drugs.

The 2023 data continue to document stable or declining trends in the use of illicit drugs among young people over many years. However, importantly, other research has reported a dramatic rise in overdose deaths among teens between 2010 to 2021, which remained elevated well into 2022 according to a NIDA analysis of CDC and Census data. This increase is largely attributed to illicit fentanyl, a potent synthetic drug, contaminating the supply of counterfeit pills made to resemble prescription medications. Taken together, these data suggest that while drug use is not becoming more common among young people, it is becoming more dangerous.

When asked a range of questions about the perceived harmfulness of occasionally taking specific prescription medications (such as OxyContin and Vicodin), or the risk of “narcotics other than heroin” overall, the percentage of students who reported perceiving a “great risk” ranged from 22.9% among eighth graders to 52.9% among 12th graders. The percentage of respondents who reported perceiving a “great risk” associated with taking Adderall occasionally ranged from 28.1% among eighth graders to 39.6% among 12th graders.

“Research has shown that delaying the start of substance use among young people, even by one year, can decrease substance use for the rest of their lives. We may be seeing this play out in real time,” said Nora Volkow, M.D., NIDA director. “This trend is reassuring. Though, it remains crucial to continue to educate young people about the risks and harms of substance use in an open and honest way, emphasizing that illicit pills and other substances may contain deadly fentanyl.”

When breaking down the data by specific drugs, the survey found that adolescents most commonly reported use of alcohol, nicotine vaping, and cannabis in the past year, and levels generally declined from or held steady with the lowered use reported in 2022. Compared to levels reported in 2022, data reported in 2023 show:

- Alcohol use remained stable for eighth and 10th graders, with 15.1% and 30.6% reporting use in the past year respectively, and declined for 12th graders, with 45.7% reporting use in the past year (compared to 51.9% in the previous year).

- Nicotine vaping remained stable for eighth graders, with 11.4% reporting vaping nicotine in the past year. It declined in the older grades, from 20.5% to 17.6% in 10th grade and from 27.3% to 23.2% in 12th grade.

- Cannabis use remained stable for all three grades surveyed, with 8.3% of eighth graders, 17.8% of 10th graders, and 29.0% of 12th graders reporting cannabis use in the past year. Of note, 6.5% of eighth graders, 13.1% of 10th graders, and 19.6% of 12th graders reported vaping cannabis within the past year, reflecting a stable trend among all three grades.

- Delta-8-THC (a psychoactive substance found in the Cannabis sativa plant, of which marijuana and hemp are two varieties) use was measured for the first time in 2023, with 11.4% of 12th graders reporting use in the past year. Beginning in 2024, eighth and 10th graders will also be asked about Delta-8 use.

- Any illicit drug use other than marijuana also remained stable for all three grades surveyed, with 4.6% of eighth graders, 5.1% of 10th graders, and 7.4% of 12th graders reporting any illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past year. These data build on long-term trends documenting low and fairly steady use of illicit substances reported among teenagers – including past-year use of cocaine, heroin, and misuse of prescription drugs, generally.

- Use of narcotics other than heroin (including Vicodin, OxyContin, Percocet, etc.) decreased among 12th graders, with 1.0% reporting use within the past year (matching the all-time low reported in 2021 and down from a high of 9.5% in 2004).

- Abstaining, or not using, marijuana, alcohol, and nicotine increased for 12th graders, with 62.6% reporting abstaining from any use of these substances over the past month. This percentage remained stable for eighth and 10th graders, with 87.0% and 76.9% reporting abstaining from any use of marijuana, alcohol, and nicotine over the past month.

READ THIS: Find out more about the Monitoring the Future study, including past results and data tables, at Monitoringthefuture.org.

Substance Abuse

High-risk substance use is any use by adolescents of substances with a high risk of adverse outcomes (i.e., injury, criminal justice involvement, school dropout, loss of life). This includes misuse of prescription drugs, use of illicit drugs (i.e., cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, inhalants, hallucinogens, or ecstasy), and use of injection drugs which have a high risk of infection of blood-borne diseases such as HIV and hepatitis (CDC, 2022)

The facts (CDC, 2022):

- 15% of high school students reported having ever used select illicit or injection drugs (i.e. cocaine, inhalants, heroin, methamphetamines, hallucinogens, or ecstasy)

- 14% of students reported misusing prescription opioids.

- Injection drug use places youth at direct risk for HIV, and drug use broadly places youth at risk of overdose.

- Youth opioid use is directly linked to sexual risk behaviors.

- Students who report ever using prescription drugs without a doctor’s prescription are more likely than other students to have been the victim of physical or sexual dating violence.

- Drug use is associated with sexual risk behavior, experience of violence, and mental health and suicide risks.

Risk and Protective Factors of Drug Use (CDC, 2022) |

|

| Risk factors for youth high-risk substance use can include:

|

Research has improved our understanding of factors that help buffer youth from a variety of risky behaviors, including substance use. These are known as protective factors. Some protective factors against high risk substance use include: |

|

|

CLICK OR CALL THIS: If you or someone you know if struggling with substance abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration of the US government has a National Helpline that provides free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders. Call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or visit https://findtreatment.gov/.

Cognitive Development

Adolescence is a time of rapid cognitive development. Biological changes in brain structure and connectivity in the brain interact with increased experience, knowledge, and changing social demands to produce rapid cognitive growth. These changes generally begin at puberty or shortly thereafter, and some skills continue to develop as an adolescent ages. Development of executive functions, or cognitive skills that enable the control and coordination of thoughts and behavior, are generally associated with the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. The thoughts, ideas, and concepts developed at this period of life greatly influence one’s future life and play a major role in character and personality formation.

Risk-taking

Because most injuries sustained by adolescents are related to risky behavior (alcohol consumption and drug use, reckless or distracted driving, and unprotected sex), a great deal of research has been done on the cognitive and emotional processes underlying adolescent risk-taking. In addressing this question, it is important to distinguish whether adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behaviors (prevalence), whether they make risk-related decisions similarly or differently than adults (cognitive processing perspective), or whether they use the same processes but value different things and thus arrive at different conclusions. The behavioral decision-making theory proposes that adolescents and adults both weigh the potential rewards and consequences of an action. However, research has shown that adolescents seem to give more weight to rewards, particularly social rewards, than do adults. Adolescents value social warmth and friendship, and their hormones and brains are more attuned to those values than to long-term consequences (Crone & Dahl, 2012).

Some have argued that there may be evolutionary benefits to an increased propensity for risk-taking in adolescence. For example, without a willingness to take risks, teenagers would not have the motivation or confidence necessary to leave their family of origin. In addition, from a population perspective, there is an advantage to having a group of individuals willing to take more risks and try new methods, counterbalancing the more conservative elements more typical of the received knowledge held by older adults.

Perspectives and Advancements in Adolescent Thinking

There are two perspectives on adolescent thinking: constructivist and information-processing. The constructivist perspective, based on the work of Piaget, takes a quantitative, stage-theory approach. This view hypothesizes that adolescents’ cognitive improvement is relatively sudden and drastic. The information-processing perspective derives from the study of artificial intelligence and explains cognitive development in terms of the growth of specific components of the overall process of thinking.

Improvements in basic thinking abilities generally occur in five areas during adolescence:

- Attention. Improvements are seen in selective attention (the process by which one focuses on one stimulus while tuning out another), as well as divided attention (the ability to pay attention to two or more stimuli at the same time).

- Memory. Improvements are seen in working memory and long-term memory.

- Processing Speed. Adolescents think more quickly than children. Processing speed improves sharply between age five and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and does not appear to change between late adolescence and adulthood.

- Organization. Adolescents are more aware of their own thought processes and can use mnemonic devices and other strategies to think and remember information more efficiently.

- Metacognition. Adolescents can think about thinking itself. This often involves monitoring one’s own cognitive activity during the thinking process. Metacognition provides the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action, and provide alternative explanations of events.

Formal Operational Thought

In the last of the Piagetian stages, a child becomes able to reason not only about tangible objects and events, but also about hypothetical or abstract ones. Hence it has the name formal operational stage—the period when the individual can “operate” on “forms” or representations. This allows an individual to think and reason with a wider perspective. This stage of cognitive development, termed by Piaget as formal operational thought, marks a movement from an ability to think and reason from concrete visible events to an ability to think hypothetically and entertain what-if possibilities about the world. An individual can solve problems through abstract concepts and utilize hypothetical and deductive reasoning. Adolescents use trial and error to solve problems, and the ability to systematically solve a problem in a logical and methodical way emerges.

WATCH THIS video below or online explaining some of the cognitive development consistent with formal operational thought. You can view the transcript for “Formal operational stage – Intro to Psychology” here).

Formal Operational Thinking in the Classroom

School is a main contributor in guiding students towards formal operational thought. With students at this level, the teacher can pose hypothetical (or contrary-to-fact) problems: “What if the world had never discovered oil?” or “What if the first European explorers had settled first in California instead of on the East Coast of the United States?” To answer such questions, students must use hypothetical reasoning, meaning that they must manipulate ideas that vary in several ways at once, and do so entirely in their minds.

The hypothetical reasoning that concerned Piaget primarily involved scientific problems. His studies of formal operational thinking therefore often look like problems that middle or high school teachers pose in science classes. In one problem, for example, a young person is presented with a simple pendulum, to which different amounts of weight can be hung (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). The experimenter asks: “What determines how fast the pendulum swings: the length of the string holding it, the weight attached to it, or the distance that it is pulled to the side?” The young person is not allowed to solve this problem by trial-and-error with the materials themselves, but must reason a way to the solution mentally. To do so systematically, they must imagine varying each factor separately, while also imagining the other factors that are held constant. This kind of thinking requires facility at manipulating mental representations of the relevant objects and actions—precisely the skill that defines formal operations.

As you might suspect, students with an ability to think hypothetically have an advantage in many kinds of school work: by definition, they require relatively few “props” to solve problems. In this sense they can in principle be more self-directed than students who rely only on concrete operations—certainly a desirable quality in the opinion of most teachers. Note, though, that formal operational thinking is desirable but not sufficient for school success, and that it is far from being the only way that students achieve educational success. Formal thinking skills do not insure that a student is motivated or well-behaved, for example, nor does it guarantee other desirable skills. The fourth stage in Piaget’s theory is really about a particular kind of formal thinking, the kind needed to solve scientific problems and devise scientific experiments. Since many people do not normally deal with such problems in the normal course of their lives, it should be no surprise that research finds that many people never achieve or use formal thinking fully or consistently, or that they use it only in selected areas with which they are very familiar (Case & Okomato, 1996). For teachers, the limitations of Piaget’s ideas suggest a need for additional theories about development—ones that focus more directly on the social and interpersonal issues of childhood and adolescence.

Hypothetical and abstract thinking

One of the major premises of formal operational thought is the capacity to think of possibility, not just reality. Adolescents’ thinking is less bound to concrete events than that of children; they can contemplate possibilities outside the realm of what currently exists. One manifestation of the adolescent’s increased facility with thinking about possibilities is the improvement of skill in deductive reasoning (also called top-down reasoning), which leads to the development of hypothetical thinking. This provides the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action and to provide alternative explanations of events. It also makes adolescents more skilled debaters, as they can reason against a friend’s or parent’s assumptions. Adolescents also develop a more sophisticated understanding of probability.

This appearance of more systematic, abstract thinking allows adolescents to comprehend the sorts of higher-order abstract logic inherent in puns, proverbs, metaphors, and analogies. Their increased facility permits them to appreciate the ways in which language can be used to convey multiple messages, such as satire, metaphor, and sarcasm. (Children younger than age nine often cannot comprehend sarcasm at all). This also permits the application of advanced reasoning and logical processes to social and ideological matters such as interpersonal relationships, politics, philosophy, religion, morality, friendship, faith, fairness, and honesty.

Metacognition

Metacognition refers to “thinking about thinking.” It is relevant in social cognition as it results in increased introspection, self-consciousness, and intellectualization. Adolescents are much better able to understand that people do not have complete control over their mental activity. Being able to introspect may lead to forms of egocentrism, or self-focus, in adolescence. Adolescent egocentrism is a term that David Elkind used to describe the phenomenon of adolescents’ inability to distinguish between their perception of what others think about them and what people actually think in reality. Elkind’s theory on adolescent egocentrism is drawn from Piaget’s theory on cognitive developmental stages, which argues that formal operations enable adolescents to construct imaginary situations and abstract thinking.

Accordingly, adolescents are able to conceptualize their own thoughts and conceive of other people’s thoughts. However, Elkind pointed out that adolescents tend to focus mostly on their own perceptions, especially on their behaviors and appearance, because of the “physiological metamorphosis” they experience during this period. This leads to adolescents’ belief that other people are as attentive to their behaviors and appearance as they are of themselves. According to Elkind, adolescent egocentrism results in two distinct problems in thinking: the imaginary audience and the personal fable. These likely peak at age fifteen, along with self-consciousness in general.

Imaginary audience is a term that Elkind used to describe the phenomenon that an adolescent anticipates the reactions of other people to them in actual or impending social situations. Elkind argued that this kind of anticipation could be explained by the adolescent’s preoccupation that others are as admiring or as critical of them as they are of themselves. As a result, an audience is created, as the adolescent believes that they will be the focus of attention.

However, more often than not the audience is imaginary because in actual social situations individuals are not usually the sole focus of public attention. Elkind believed that the construction of imaginary audiences would partially account for a wide variety of typical adolescent behaviors and experiences; and imaginary audiences played a role in the self-consciousness that emerges in early adolescence. However, since the audience is usually the adolescent’s own construction, it is privy to their own knowledge of themselves. According to Elkind, the notion of imaginary audience helps to explain why adolescents usually seek privacy and feel reluctant to reveal themselves–it is a reaction to the feeling that one is always on stage and constantly under the critical scrutiny of others.

Elkind also addressed that adolescents have a complex set of beliefs that their own feelings are unique and they are special and immortal. Personal fable is the term Elkind created to describe this notion, which is the complement of the construction of imaginary audience. Since an adolescent usually fails to differentiate their own perceptions and those of others, they tend to believe that they are of importance to so many people (the imaginary audiences) that they come to regard their feelings as something special and unique. They may feel that only they have experienced strong and diverse emotions, and therefore others could never understand how they feel. This uniqueness in one’s emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent’s belief of invincibility, especially to death.

This adolescent belief in personal uniqueness and invincibility becomes an illusion that they can be above some of the rules, disciplines and laws that apply to other people; even consequences such as death (called the invincibility fable). This belief that one is invincible removes any impulse to control one’s behavior (Lin, 2016). Therefore, adolescents will engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences.

Intuitive and Analytic Thinking

Piaget emphasized the sequence of thought throughout four stages. Others suggest that thinking does not develop in sequence, but instead, that advanced logic in adolescence may be influenced by intuition. Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the dual-process model; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Kuhn, 2013.) Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional.

In contrast, analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational (logical). While these systems interact, they are distinct (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier, quicker, and more commonly used in everyday life. As discussed in the adolescent brain development section earlier in this module, the discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults. As adolescents develop, they gain in logic/analytic thinking ability and sometimes regress, with social context, education, and experiences becoming major influences. Simply put, being “smarter” as measured by an intelligence test does not advance cognition as much as having more experience, in school and in life (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014).

Relativistic Thinking

Adolescents are more likely to engage in relativistic thinking—in other words, they are more likely to question others’ assertions and less likely to accept information as absolute truth. Through experience outside the family circle, they learn that rules they were taught as absolute are actually relativistic. They begin to differentiate between rules crafted from common sense (don’t touch a hot stove) and those that are based on culturally relative standards (codes of etiquette). This can lead to a period of questioning authority in all domains.

As we continue through this module, we will discuss how this influences moral reasoning, as well as psychosocial and emotional development. These more abstract developmental dimensions (cognitive, moral, emotional, and social dimensions) are not only subtler and more difficult to measure, but these developmental areas are also difficult to tease apart from one another due to the inter-relationships among them. For instance, our cognitive maturity will influence the way we understand a particular event or circumstance, which will in turn influence our moral judgments about it, and our emotional responses to it. Similarly, our moral code and emotional maturity influence the quality of our social relationships with others.

Psychosocial Development

Identity

Identity development is a stage in the adolescent life cycle. For most, the search for identity begins in the adolescent years. During these years, adolescents are more open to ‘trying on’ different behaviors and appearances to discover who they are. In an attempt to find their identity and discover who they are, adolescents are likely to cycle through a number of identities to find one that suits them best. Developing and maintaining identity (in adolescent years) is a difficult task due to multiple factors such as family life, environment, and social status. Empirical studies suggest that this process might be more accurately described as identity development, rather than formation, but confirms a normative process of change in both content and structure of one’s thoughts about the self.

Self-Concept

Two main aspects of identity development are self-concept and self-esteem. The idea of self-concept is known as the ability of a person to have opinions and beliefs that are defined confidently, consistently and with stability. Early in adolescence, cognitive developments result in greater self-awareness, greater awareness of others and their thoughts and judgments, the ability to think about abstract, future possibilities, and the ability to consider multiple possibilities at once. As a result, adolescents experience a significant shift from the simple, concrete, and global self-descriptions typical of young children; as children they defined themselves by physical traits whereas adolescents define themselves based on their values, thoughts, and opinions.

Adolescents can conceptualize multiple “possible selves” that they could become and long-term possibilities and consequences of their choices. Exploring these possibilities may result in abrupt changes in self-presentation as the adolescent chooses or rejects qualities and behaviors, trying to guide the actual self toward the ideal self (who the adolescent wishes to be) and away from the feared self (who the adolescent does not want to be). For many, these distinctions are uncomfortable, but they also appear to motivate achievement through behavior consistent with the ideal and distinct from the feared possible selves.

Further distinctions in self-concept, called “differentiation,” occur as the adolescent recognizes the contextual influences on their own behavior and the perceptions of others, and begin to qualify their traits when asked to describe themselves. Differentiation appears fully developed by mid-adolescence. Peaking in the 7th-9th grades, the personality traits adolescents use to describe themselves refer to specific contexts, and therefore may contradict one another. The recognition of inconsistent content in the self-concept is a common source of distress in these years, but this distress may benefit adolescents by encouraging structural development.

Self-Esteem

Another aspect of identity formation is self-esteem. Self-esteem is defined as one’s thoughts and feelings about one’s self-concept and identity. Most theories on self-esteem state that there is a grand desire, across all genders and ages, to maintain, protect and enhance their self-esteem. Contrary to popular belief, there is no empirical evidence for a significant drop in self-esteem over the course of adolescence. “Barometric self-esteem” fluctuates rapidly and can cause severe distress and anxiety, but baseline self-esteem remains highly stable across adolescence. The validity of global self-esteem scales has been questioned, and many suggest that more specific scales might reveal more about the adolescent experience. Girls are most likely to enjoy high self-esteem when engaged in supportive relationships with friends, the most important function of friendship to them is having someone who can provide social and moral support. When they fail to win friends’ approval or can’t find someone with whom to share common activities and common interests, in these cases, girls suffer from low self-esteem.

In contrast, boys are more concerned with establishing and asserting their independence and defining their relation to authority. As such, they are more likely to derive high self-esteem from their ability to successfully influence their friends; on the other hand, the lack of romantic competence, for example, failure to win or maintain the affection of another or the same-sex (depending on sexual orientation), is the major contributor to low self-esteem in adolescent boys.

Identity Formation: Who am I?

Adolescents continue to refine their sense of self as they relate to others. Erik Erikson referred to life’s fifth psychosocial task as one of identity versus role confusion when adolescents must work through the complexities of finding one’s own identity. Individuals are influenced by how they resolved all of the previous childhood psychosocial crises and this adolescent stage is a bridge between the past and the future, between childhood and adulthood. Thus, in Erikson’s view, an adolescent’s main questions are “Who am I?” and “Who do I want to be?” Identity formation was highlighted as the primary indicator of successful development during adolescence (in contrast to role confusion, which would be an indicator of not successfully meeting the task of adolescence). This crisis is resolved positively with identity achievement and the gain of fidelity (ability to be faithful) as a new virtue, when adolescents have reconsidered the goals and values of their parents and culture. Some adolescents adopt the values and roles that their parents expect for them. Other teens develop identities that are in opposition to their parents but align with a peer group. This is common as peer relationships become a central focus in adolescents’ lives.

Expanding on Erikson’s theory, Marcia (1966) described identity formation during adolescence as involving both decision points and commitments with respect to ideologies (e.g., religion, politics) and occupations. Foreclosure occurs when an individual commits to an identity without exploring options. Identity confusion/diffusion occurs when adolescents neither explore nor commit to any identities. Moratorium is a state in which adolescents are actively exploring options but have not yet made commitments. As mentioned earlier, individuals who have explored different options, discovered their purpose, and have made identity commitments are in a state of identity achievement.

WATCH THIS video below or online taking a deeper look at Marcia’s theory of identity development and relating the four identity statuses to college students figuring out their major. You can view the transcript for “James Marcia’s Adolescent Identity Development” here.

Developmental psychologists have researched several different areas of identity development and some of the main areas include:

Religious identity: The religious views of teens are often similar to those of their families (Kim-Spoon, Longo, & McCullough, 2012). Most teens may question specific customs, practices, or ideas in the faith of their parents, but few completely reject the religion of their families.

Political identity: An adolescent’s political identity is also influenced by their parents’ political beliefs. A new trend in the 21st century is a decrease in party affiliation among adults. Many adults do not align themselves with either the democratic or republican party and their teenage children reflect their parents’ lack of party affiliation. Although adolescents do tend to be more liberal than their elders, especially on social issues (Taylor, 2014), like other aspects of identity formation, adolescents’ interest in politics is predicted by their parents’ involvement and by current events (Stattin et al., 2017).

Vocational identity: While adolescents in earlier generations envisioned themselves as working in a particular job, and often worked as an apprentice or part-time in such occupations as teenagers, this is rarely the case today. Vocational identity takes longer to develop, as most of today’s occupations require specific skills and knowledge that will require additional education or are acquired on the job itself. In addition, many of the jobs held by teens are not in occupations that most teens will seek as adults.

Vocational identity as a health care professional: Many students reading this text are seeking a career as a healthcare professional. Ensuring a professional identity while working as a health care provider can “prevent burnout, fatigue, mental and physical stress, moral distress, and moral injury; and promote work satisfaction and retention” (Owens and Godfrey, 2022). The International Society for Professional Identity in Nursing has four domains to work within when developing your vocational identity. These are Values and Ethics, Knowledge, Nurse as Leader and Professional Comportment (behavior).

READ THIS Read more about developing a professional identity in nursing in the article “Fostering professional identity in nursing.”

Ethnic identity: Ethnic identity refers to how people come to terms with who they are based on their ethnic or racial ancestry. According to the U.S. Census (2012) more than 40% of Americans under the age of 18 are from historically marginalized ethnoracial groups. For many BIPOC teens, discovering one’s ethnoracial identity is an important part of identity formation. Phinney (1989) proposed a model of ethnic identity development that included stages of unexplored ethnic identity, ethnic identity search, and achieved ethnic identity.

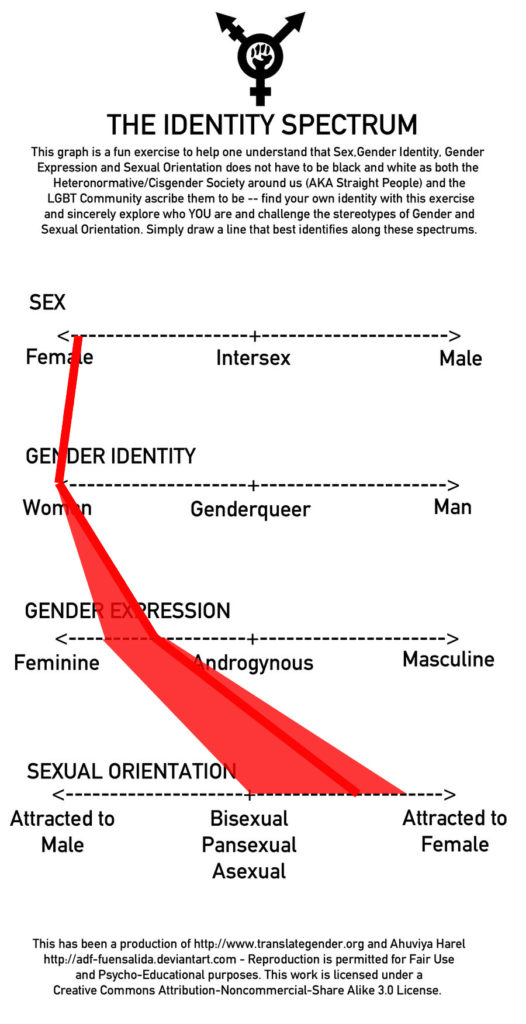

Gender identity: A person’s sex assigned at birth, as determined by their biology, does not always correspond with their gender. Sex (assigned at birth) refers to the biological differences between males and females, such as genitalia and genetic differences. Gender refers to the socially constructed characteristics of women, men, and other genders, such as norms, roles, and relationships between groups of people. Many adolescents use their analytic, hypothetical thinking to question traditional gender roles and expression. If their sex assigned at birth does not line up with their gender identity, they may refer to themselves as transgender, non-binary, or gender-nonconforming.

Gender identity refers to a person’s self-perception as male, female, both, genderqueer, or neither. Cisgender is an umbrella term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their sex assigned at birth, while transgender is a term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Gender expression, or how one demonstrates gender (based on traditional gender role norms related to clothing, behavior, and interactions) can be feminine, masculine, androgynous, or somewhere along a spectrum.

Fluidity and uncertainty regarding sex and gender are especially common during early adolescence, when hormones increase and fluctuate, creating difficulty of self-acceptance and identity achievement (Reisner et al., 2016). Gender identity, like vocational identity, is becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. The roles appropriate for males and females are evolving and some adolescents may foreclose on a gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty by adopting more stereotypic male or female roles (Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013). Those that identify as transgender, queer, or other face even bigger challenges.

Social Development

Parents

It appears that most teens do not experience adolescent “storm and stress” to the degree once famously suggested by G. Stanley Hall, a pioneer in the study of adolescent development. Only small numbers of teens have major conflicts with their parents (Steinberg & Morris, 2001), and most disagreements are minor. For example, in a study of over 1,800 parents of adolescents from various cultural and ethnic groups, Barber (1994) found that conflicts occurred over day-to-day issues such as homework, money, curfews, clothing, chores, and friends. These disputes occur because an adolescent’s drive for independence and autonomy conflicts with the parent’s supervision and control. These types of arguments tend to decrease as teens develop (Galambos & Almeida, 1992).

As adolescents work to form their identities, they pull away from their parents, and the peer group becomes very important (Shanahan, McHale, Osgood, & Crouter, 2007). Despite spending less time with their parents, most teens report positive feelings toward them (Moore, Guzman, Hair, Lippman, & Garrett, 2004). Warm and healthy parent-child relationships have been associated with positive child outcomes, such as better grades and fewer school behavior problems, in the United States as well as in other countries (Hair et al., 2005).

Although peers take on greater importance during adolescence, family relationships remain important too. One of the key changes during adolescence involves a renegotiation of parent–child relationships. As adolescents strive for more independence and autonomy during this time, different aspects of parenting become more salient. For example, parents’ distal supervision and monitoring become more important as adolescents spend more time away from parents and in the presence of peers. Parental monitoring encompasses a wide range of behaviors such as parents’ attempts to set rules and know their adolescents’ friends, activities, and whereabouts, in addition to adolescents’ willingness to disclose information to their parents. (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Psychological control, which involves manipulation and intrusion into adolescents’ emotional and cognitive world through invalidating adolescents’ feelings and pressuring them to think in particular ways is another aspect of parenting that becomes more salient during adolescence and is related to more problematic adolescent adjustment.

Peers

As children become adolescents, they usually begin spending more time with their peers and less time with their families, and these peer interactions are increasingly unsupervised by adults. Children’s notions of friendship often focus on shared activities, whereas adolescents’ notions of friendship increasingly focus on intimate exchanges of thoughts and feelings.