7 Module 7: Middle Childhood Development

Module 7 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Describe Physical Growth

Explain the physical growth patterns in middle childhood, including the development of gross and fine motor skills. - Understand Cognitive Advances

Discuss Piaget’s concrete operational stage and how it supports logical thinking and problem-solving in middle childhood. - Examine Information Processing

Explain how memory and attention improve during middle childhood and their role in learning and critical thinking. - Explore Language Development

Describe the growth of vocabulary, grammar, and the ability to use language for humor and complex communication. - Understand Health Challenges

Identify common health issues, including childhood obesity and malnutrition, and strategies to promote wellness. - Analyze the Role of Play and Sports

Discuss the benefits and challenges of organized sports and physical activities during middle childhood. - Evaluate Peer Relationships

Explain the importance of friendships, peer acceptance, and social skills in middle childhood development. - Discuss Self-Concept and Self-Esteem

Analyze how children’s self-awareness and self-evaluations evolve during this stage. - Understand Family Dynamics

Examine the roles of family relationships, including parenting styles and the effects of divorce on children. - Apply Erikson’s Stage of Industry vs. Inferiority

Explain how this psychosocial stage influences children’s sense of competence and their motivation to succeed. - Recognize Learning Challenges

Identify common learning disabilities, such as dyslexia and ADHD, and their impact on academic and social development. - Analyze Theories of Intelligence

Compare Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences and Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence, and discuss their implications for understanding diverse abilities in children. - Address Issues of Sexual Abuse

Describe the impact of sexual abuse on children’s physical, emotional, and social development, and the importance of prevention and support. - Analyze Cultural and Environmental Influences

Discuss how cultural and environmental factors shape children’s experiences in schools and communities during middle childhood.

Introduction

Children in middle childhood go through tremendous changes in the growth and development of their brain. During this period of development children’s bodies are not only growing, but they are becoming more coordinated and physically capable. Children enter middle childhood still looking very young, and end the stage on the cusp of adolescence. Most children have gone through a growth spurt that makes them look rather grown-up. The obvious physical changes are accompanied by changes in the brain. While we don’t see the actual brain changing, we can see the effects of the brain changes in the way that children in middle childhood play sports, write, and play games. These children are more mindful of their greater abilities in school and are becoming more responsible for their health and diet. Some children may be challenged with physical or mental health concerns. It’s important to know what typical development looks like in order to identify and to help those that are struggling with health concerns.

Physical Development

Growth Rates and Motor Skills

Rates of growth generally slow during middle childhood. Typically, a child will gain about 5-7 pounds a year and grow about 2 inches per year. Many girls and boys experience a prepubescent growth spurt, but this growth spurt tends to happen earlier in girls (around age 9-10) than it does in boys (around age 11-12). Because of this, girls are often taller than boys at the end of middle childhood. Children in middle childhood tend to slim down and gain muscle strength and lung capacity making it possible to engage in strenuous physical activity for long periods of time.

The brain reaches its adult size at about age 7. That is not to say, however, that the brain is fully developed by age 7. The brain continues to develop for many years after it has attained its adult size. The school-aged child is better able to plan, coordinate activity using both left and right hemispheres of the brain, and to control emotional outbursts. Paying attention is also improved as the prefrontal cortex matures. As the myelin continues to develop throughout middle childhood, the child’s reaction time improves as well.

During middle childhood, physical growth slows down. One result of the slower rate of growth is an improvement in motor skills. Children of this age tend to sharpen their abilities to perform both gross motor skills such as riding a bike and fine motor skills such as cutting their fingernails.

Losing Primary Teeth

Deciduous teeth, commonly known as milk teeth, baby teeth, primary teeth, and temporary teeth, are the first set of teeth in the growth development of humans. The primary teeth are important for the development of the mouth, development of the child’s speech, for the child’s smile, and play a role in chewing of food. Most children lose their first tooth around age 6, then continue to lose teeth for the next 6 years. In general, children lose the teeth in the middle of the mouth first and then lose the teeth next to those in sequence over the 6-year span. By age 12, generally all of the teeth are permanent teeth, however, it is not extremely rare for one or more primary teeth to be retained beyond this age, sometimes well into adulthood, often because the secondary tooth fails to develop.

Health Risks: Childhood Obesity

Nearly 20 percent of school-aged American children are obese. This is defined as being at least 20 percent over their ideal weight. The percentage of obesity in school aged children has increased substantially since the 1960s, and it continues to increase. This is true in part because of the introduction of a steady diet of television and other sedentary activities. In addition, we have come to emphasize high fat, fast foods as a culture. Pizza, hamburgers, chicken nuggets and “lunchables” with soda have replaced more nutritious foods as staples.

One consequence of childhood obesity is that children who are overweight tend to be ridiculed and teased by others. This can certainly be damaging to their self-image and popularity. In addition, obese children run the risk of suffering orthopedic problems such as knee injuries, and an increased risk of heart disease and stroke in adulthood. It may be difficult for a child who is obese to become a non-obese adult. In addition, the number of cases of pediatric diabetes has risen dramatically in recent years.

Dieting is not really the solution to childhood obesity. If you diet, your basal metabolic rate tends to decrease thereby making the body burn even fewer calories in order to maintain the weight. Increased activity is much more effective in lowering the weight and improving the child’s health and psychological well-being. Exercise reduces stress and being an overweight child, subjected to the ridicule of others can certainly be stressful. Parents should take caution against emphasizing diet alone to avoid the development of any obsession about dieting that can lead to eating disorders as teens. Again, increasing a child’s activity level is most helpful.

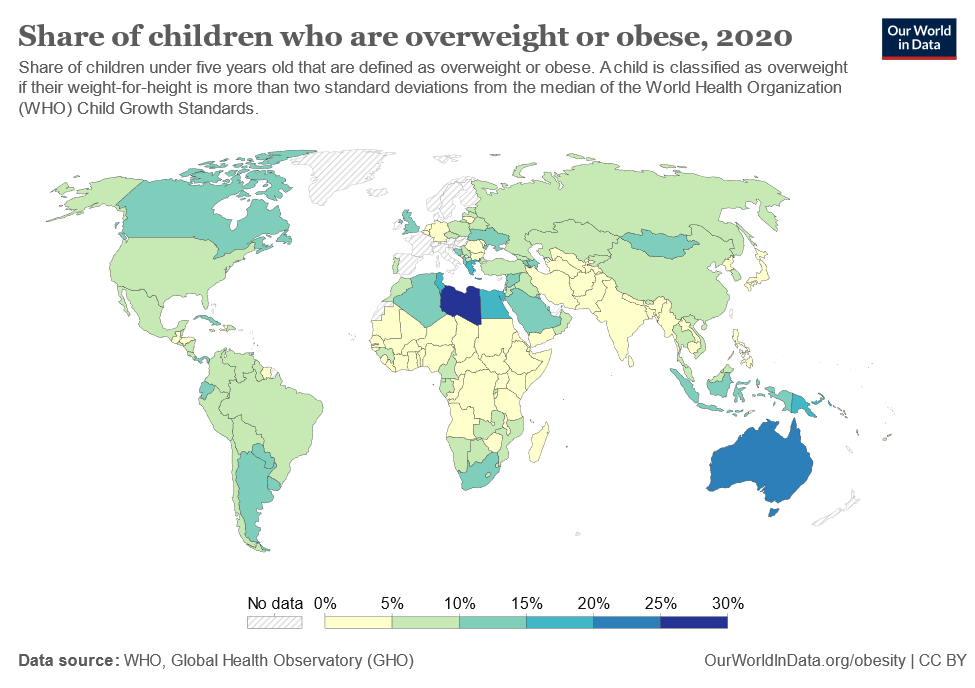

The graph below shows the percentage of children who are overweight or obese in the world during the year 2020.

CLICK THIS: You can view a time lapse and explore the data set further at the Our World in Data website.

School Lunch Programs

Many school-age children eat breakfast, snacks, and lunch at their schools. Therefore, it is important for schools to provide meals that are nutritionally sound. In the United States, more than thirty-one million children from low-income families are given meals provided by the National School Lunch Program. This federally funded program offers low-cost or free breakfast, snacks, and lunches to school facilities. School districts that take part receive subsidies from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for every meal they serve that must meet the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.Knowing that many children in the United States buy or receive free lunches in the school cafeteria, it might be worthwhile to look at the nutritional content of school lunches. You can obtain this information through your local school district’s website. An example of a school menu from a school district in north-central Texas is a meal consisting of pasta alfredo, breadstick, peach cup, tomato soup, a brownie, and 2% milk which is in compliance with Federal Nutritional Guidelines. Consider another menu from an elementary school in the state of Washington. This sample meal consists of chicken burger, tater tots, fruit, veggies, and 1% or nonfat milk. This meal is also in compliance with Federal Nutrition Guidelines but has about 300 fewer calories than the menu in Texas. This is a big difference in calories and nutritional value of these prepared lunches that are chosen and approved by officials on behalf of children in these districts.

Healthy School Lunch Campaigns helps to promote children’s health. This is done by educating government officials, school officials, food-service workers, and parents and is sponsored by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. They educate and encourage schools to offer low-fat, cholesterol-free options in school cafeterias and in vending machines and work to improve the food served to children at school. Unfortunately, many school districts in the nation allow students to purchase chips, cookies, and ice cream along with their meals. These districts rely on the sale of these items in the lunchrooms to earn additional revenues. Not only are they making money off of children and families with junk food, but they are also adding additional empty calories to their daily intake. These districts need to look at the menus and determine the rationale for offering additional snacks and desserts for children at their schools. Whether children receive free lunches, buy their own, or bring their lunch from home, quality nutrition is what is best for these growing bodies and minds.

Children and Malnutrition

Many may not know that malnutrition is a problem that many children face, in both developing nations and the developed world. Even with the wealth of food in North America, many children grow up malnourished, or even hungry. The US Census Bureau characterizes households into the following groups:

- food secure

- food insecure without hunger

- food insecure with moderate hunger

- food insecure with severe hunger

Millions of children grow up in food-insecure households with inadequate diets due to both the amount of available food and the quality of food. In the United States, about 20 percent of households with children are food insecure to some degree. In half of those, only adults experience food insecurity, while in the other half both adults and children are considered to be food insecure, which means that children did not have access to adequate, nutritious meals at times.

Growing up in a food-insecure household can lead to a number of problems. Deficiencies in iron, zinc, protein, and vitamin A can result in stunted growth, illness, and limited development. Federal programs, such as the National School Lunch Program, the School Breakfast Program, and Summer Feeding Programs, work to address the risk of hunger and malnutrition in school-aged children. They help to fill the gaps and provide children living in food-insecure households with greater access to nutritious meals.

Exercise, physical fitness and sports

Recess and Physical Education

Recess is a time for free play and Physical Education (PE) is a structured program that teaches skills, rules, and games. They’re a big part of physical fitness for school-age children. For many children, PE and recess are the key components in introducing children to sports. After years of schools cutting back on recess and PE programs, there has been a turnaround, prompted by concerns over childhood obesity and the related health issues. Despite these changes, currently, only the state of Oregon and the District of Columbia meet PE guidelines of a minimum of 150 minutes per week of physical activity in elementary school and 225 minutes in middle school (SPARC, 2016).

Organized sports

Middle childhood seems to be a great time to introduce children to organized sports. And in fact, many parents do. Nearly 3 million children play soccer in the United States. This activity promises to help children build social skills, improve athletically, and learn a sense of competition. It has been suggested, however, that the emphasis on competition and athletic skill can be counterproductive and lead children to grow tired of the game and want to quit. In many respects, it appears that children’s activities are no longer children’s activities once adults become involved and approach the games as adults rather than children. The U.S. Soccer Federation recently advised coaches to reduce the amount of drilling engaged in during practice and to allow children to play more freely and to choose their own positions. The hope is that this will build on their love of the game and foster their natural talents.

Sports are important for children. Children’s participation in sports has been linked to:

- Higher levels of satisfaction with family and overall quality of life in children

- Improved physical and emotional development

- Better academic performance

Yet, a study on children’s sports in the United States (Sabo & Veliz, 2008) has found that gender, poverty, location, ethnicity, and disability can limit opportunities to engage in sports. Girls were more likely to have never participated in any type of sport.

This study also found that fathers may not be providing their daughters as much support as they do their sons. While boys rated their fathers as their biggest mentor who taught them the most about sports, girls rated coaches and physical education teachers as their key mentors. Sabo and Veliz also found that children in suburban neighborhoods had a much higher participation in sports than boys and girls living in rural or urban centers. In addition, Caucasian girls and boys participated in organized sports at higher rates than children from minoritized groups.

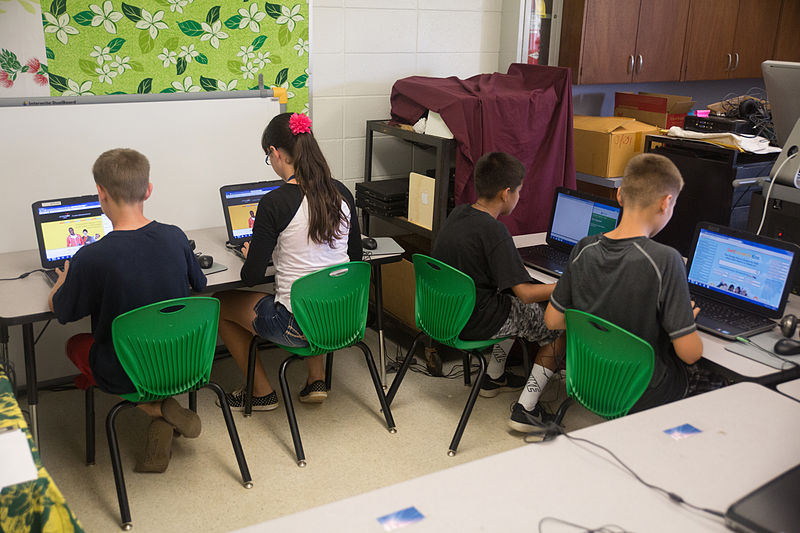

Welcome to the World of E-Sports

The recent Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (2016) report on the “State of Play” in the United States highlights a disturbing trend. One in four children between the ages of 5 and 16 rate playing computer games with their friends as a form of exercise. In addition, e-sports, which as SPARC writes is about as much a sport as poker, involves children watching other children play video games. Over half of males, and about 20% of females, aged 12-19, say they are fans of e-sports. Play is an important part of childhood and physical activity has been proven to help children develop and grow. Adults and caregivers should look at what children are doing within their day to prioritize the activities that should be focused on.

Cognitive Development

Children in middle childhood are beginning a new experience—that of formal education. In the United States, formal education begins at a time when children are beginning to think in new and more sophisticated ways. According to Piaget, the child is entering a new stage of cognitive development where they are improving their logical skills. During middle childhood, children also make improvements in short-term and long-term memory.

Concrete Operational Thought

According to Piaget, children in early childhood are in the preoperational stage of development in which they learn to think symbolically about the world. From ages 7 to 11, the school-aged child continues to develop in what Piaget referred to as the concrete operational stage of cognitive development. This involves mastering the use of logic in concrete ways. The child can use logic to solve problems tied to their own direct experience but has trouble solving hypothetical problems or considering more abstract problems. The child uses inductive reasoning, which means thinking that the world reflects one’s own personal experience. For example, a child has one friend who is rude, another friend who is also rude, and the same is true for a third friend. Using inductive reasoning, the child may conclude that friends are rude. (We will see that this way of thinking tends to change during adolescence as children begin to use deductive reasoning effectively.)

The word concrete refers to that which is tangible; that which can be seen or touched or experienced directly. The concrete operational child is able to make use of logical principles in solving problems involving the physical world. For example, the child can understand the principles of cause and effect, size, and distance.

As children’s experiences and vocabularies grow, they build schema and are able to classify objects in many different ways. Classification can include new ways of arranging information, categorizing information, or creating classes of information. Many psychological theorists, including Piaget, believe that classification involves a hierarchical structure, such that information is organized from very broad categories to very specific items.

One feature of concrete operational thought is the understanding that objects have an identity or qualities that do not change even if the object is altered in some way. For instance, the mass of an object does not change by rearranging it. A piece of chalk is still chalk even when the piece is broken in two.

During middle childhood, children also understand the concept of reversibility, or that some things that have been changed can be returned to their original state. Water can be frozen and then thawed to become liquid again. But eggs cannot be unscrambled. Arithmetic operations are reversible as well: 2 + 3 = 5 and 5 – 3 = 2. Many of these cognitive skills are incorporated into the school’s curriculum through mathematical problems and in worksheets about which situations are reversible or irreversible. (If you have access to children’s school papers, look for examples of these.)

Remember from early childhood, children thinking that a tall beaker filled with 8 ounces of water was “more” than a short, wide bowl filled with 8 ounces of water? Concrete operational children can understand the concept of reciprocity which means that changing one quality (in this example, height or water level) can be compensated for by changes in another quality (width). So, there is the same amount of water in each container although one is taller and narrower and the other is shorter and wider. These new cognitive skills increase the child’s understanding of the physical world. Operational or logical thought about the abstract world comes later.

Learning, memory and problem-solving

During middle childhood, children are able to learn and remember due to an improvement in the ways they attend to and store information. As children enter school and learn more about the world, they develop more categories for concepts and learn more efficient strategies for storing and retrieving information. One significant reason is that they continue to have more experiences on which to tie new information. New experiences are similar to old ones or remind the child of something else about which they know. This helps them file away new experiences more easily.

Children in middle childhood also have a better understanding of how well they are performing on a task and the level of difficulty of a task. As they become more realistic about their abilities, they can adapt studying strategies to meet those needs. While preschoolers may spend as much time on an unimportant aspect of a problem as they do on the main point, school-aged children start to learn to prioritize and gauge what is significant and what is not. They develop metacognition or the ability to understand the best way to figure out a problem. They gain more tools and strategies (such as “i before e except after c” so they know that “receive” is correct but “recieve” is not.)

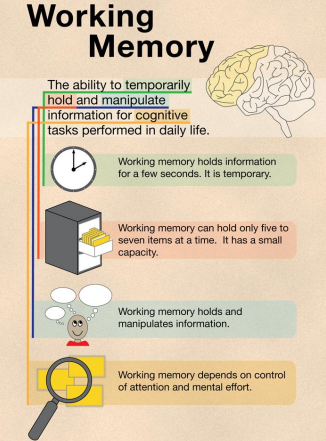

During middle and late childhood children make strides in several areas of cognitive function including the capacity of working memory, their ability to pay attention, and their use of memory strategies. Both changes in the brain and experience foster these abilities. In this section, we will look at how children process information, think and learn, allowing them to increase their ability to learn and remember due to an improvement in the ways they attend to, store information, and problem solve.

Information Processing Theory

Information processing theory is a classic theory of memory that compares the way in which the mind works to computer storing, processing and retrieving information. According to the theory, there are three levels of memory:

1) Sensory memory: Information first enters our sensory memory (sometimes called sensory register). Stop reading and look around the room very quickly. (Yes, really. Do it!) Okay. What do you remember? Chances are, not much, even though EVERYTHING you saw and heard entered into your sensory memory. And although you might have heard yourself sigh, caught a glimpse of your dog walking across the room, and smelled the soup on the stove, you may not have registered those sensations. Sensations are continuously coming into our brains, and yet most of these sensations are never really perceived or stored in our minds. They are lost after a few seconds because they were immediately filtered out as irrelevant. If the information is not perceived or stored, it is discarded quickly.

2) Working memory (short-term memory): The capacity of working memory expands during middle and late childhood, research has suggested that both an increase in processing speed and the ability to inhibit irrelevant information from entering memory are contributing to the greater efficiency of working memory during this age (de Ribaupierre, 2002). Changes in myelination and synaptic pruning in the cortex are likely behind the increase in processing speed and ability to filter out irrelevant stimuli (Kail, McBride-Chang, Ferrer, Cho, & Shu, 2013).

If information is meaningful (either because it reminds us of something else or because we must remember it for something like a history test we will be taking in 5 minutes), it moves from sensory memory into our working memory. The process by which this happens is not entirely clear. Working memory consists of information that we are immediately and consciously aware of. All of the things on your mind at this moment are part of your working memory.

There is a limited amount of information that can be kept in the working memory at any given time. For most people, this is somewhere around 7 + or – 2 pieces or chunks of information. If you are given too much information at a time, you may lose some of it. (Have you ever been writing down notes in a class and the instructor speaks too quickly for you to get it all in your notes? You are trying to get it down and out of your working memory to make room for new information and if you cannot “dump” that information onto your paper and out of your mind quickly enough, you lose what has been said.)

Rehearsal can help you maintain information in your working memory, but the process by which information moves from working memory into long term memory seems to rely on more than simple rehearsal. Information in our working memory must be stored in an effective way in order to be accessible to us for later use. It is stored in our long-term memory or knowledge base.

3) Long-term memory (knowledge base): This level of memory has an unlimited capacity and stores information for days, months or years. It consists of things that we know of or can remember if asked. This is where you want the information to ultimately be stored. The important thing to remember about storage is that it must be done in a meaningful or effective way. In other words, if you simply try to repeat something several times in order to remember it, you may only be able to remember the sound of the word rather than the meaning of the concept. So if you are asked to explain the meaning of the word or to apply a concept in some way, you will be lost. Studying involves organizing information in a meaningful way for later retrieval. Passively reading a text is usually inadequate and should be thought of as the first step in learning material. Writing keywords, thinking of examples to illustrate their meaning, and considering ways that concepts are related are all techniques helpful for organizing information for effective storage and later retrieval.

Attention

As noted above, the ability to inhibit irrelevant information improves during this age group, with there being a sharp improvement in selective attention from age six into adolescence (Vakil, Blachstein, Sheinman, & Greenstein, 2009). Children also improve in their ability to shift their attention between tasks or different features of a task (Carlson, Zelazo, & Faja, 2013). A younger child who is asked to sort objects into piles based on the type of object, car versus animal, or color of the object, red versus blue, would likely have no trouble doing so. But if you ask them to switch from sorting based on type to now having them sort based on color, they would struggle because this requires them to suppress the prior sorting rule. An older child has less difficulty making the switch, meaning there is greater flexibility in their intentional skills. These changes in attention and working memory contribute to children having more strategic approaches to challenging tasks.

Memory Strategies

Bjorklund (2005) describes a developmental progression in the acquisition and use of memory strategies. Such strategies are often lacking in younger children, but increase in frequency as children progress through elementary school. Examples of memory strategies include rehearsing information you wish to recall, visualizing and organizing information, creating rhymes, such as “i” before “e” except after “c”, or inventing acronyms, such as “roygbiv” to remember the colors of the rainbow. Schneider, Kron-Sperl, and Hünnerkopf (2009) reported a steady increase in the use of memory strategies from ages six to ten in their longitudinal study. Moreover, by age ten many children were using two or more memory strategies to help them recall information. Schneider and colleagues found that there were considerable individual differences at each age in the use of strategies and that children who utilized more strategies had better memory performance than their same-aged peers.

As children enter school and learn more about the world, they develop more categories for concepts and learn more efficient strategies for storing and retrieving information. One significant reason is that they continue to have more experiences on which to tie new information. In other words, their knowledge base, knowledge in particular areas that makes learning new information easier, expands (Berger, 2014).

Metacognition refers to the knowledge we have about our own thinking and our ability to use this awareness to regulate our own cognitive processes (Bruning, Schraw, Norby, & Ronning, 2004). Children in this developmental stage also have a better understanding of how well they are performing a task and the level of difficulty of a task. As they become more realistic about their abilities, they can adapt studying strategies to meet those needs. Young children spend as much time on an unimportant aspect of a problem as they do on the main point, while older children start to learn to prioritize and gauge what is significant and what is not. As a result, they develop metacognition.

Critical thinking, or a detailed examination of beliefs, courses of action, and evidence, involves teaching children how to think. The purpose of critical thinking is to evaluate information in ways that help us make informed decisions. Critical thinking involves better understanding a problem through gathering, evaluating, and selecting information, and also by considering many possible solutions. Ennis (1987) identified several skills useful in critical thinking. These include: Analyzing arguments, clarifying information, judging the credibility of a source, making value judgments, and deciding on an action. Metacognition is essential to critical thinking because it allows us to reflect on the information as we make decisions.

Language Development

Vocabulary

One of the reasons that children can classify objects in so many ways is that they have acquired a vocabulary to do so. By 5th grade, a child’s vocabulary has grown to 40,000 words. It grows at the rate of 20 words per day, a rate that exceeds that of preschoolers. This language explosion, however, differs from that of preschoolers because it is facilitated by being able to associate new words with those already known (fast-mapping) and because it is accompanied by a more sophisticated understanding of the meanings of a word.

A child in middle childhood is also able to think of objects in less literal ways. For example, if asked for the first word that comes to mind when one hears the word “pizza”, the preschooler is likely to say “eat” or some word that describes what is done with a pizza. However, the school-aged child is more likely to place pizza in the appropriate category and say “food” or “carbohydrate”.

This sophistication of vocabulary is also evidenced in the fact that school-aged children are able to tell jokes and delight in doing so. They may use jokes that involve plays on words such as “knock-knock” jokes or jokes with punch lines. Preschoolers do not understand plays on words and rely on telling “jokes” that are literal or slapstick such as “A man fell down in the mud! Isn’t that funny?”

Grammar and Flexibility

School-aged children are also able to learn new rules of grammar with more flexibility. While preschoolers are likely to be reluctant to give up saying “I goed there”, school-aged children will learn this rather quickly along with other rules of grammar.

While the preschool years might be a good time to learn a second language (being able to understand and speak the language), the school years may be the best time to be taught a second language (the rules of grammar).

Educational Issues during Middle Childhood

When Should School Begin?

In the United States, children generally begin school around age 5 or 6. In fact, most Western countries follow this model. But WHY do we begin school at 5 or 6? For the most part, this age was chosen as a matter of convenience. In countries where the mother is expected to work, the age at which children begin school tends to be younger. That said, research does not support that children should begin formal education so early. Many research studies suggest age 7 is the most appropriate age to begin formalized school. Before age 7, children learn best through play. By age 7, most children are capable of learning in a more formal academic-forward setting.

Testing in Schools

Children’s academic performance is often measured with the use of standardized tests. Achievement tests are used to measure what a child has already learned. Achievement tests are often used as measures of teaching effectiveness within a school setting and as a method to make schools that receive tax dollars (such as public schools, charter schools, and private schools that receive vouchers) accountable to the government for their performance. In 2001, President George W. Bush signed into effect the No Child Left Behind Act mandating that schools administer achievement tests to students and publish those results so that parents have an idea of their children’s performance and the government has information on the gaps in educational achievement between children from various social class, racial, and ethnic groups. Schools that show significant gaps in these levels of performance are to work toward narrowing these gaps. Educators have criticized the policy for focusing too much on testing as the only indication of performance levels.

Aptitude tests are designed to measure a student’s ability to learn or to determine if a person has potential in a particular program. These are often used at the beginning of a course of study or as part of college entrance requirements. The Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test (PSAT) are perhaps the most familiar aptitude tests to students in grades 6 and above. Learning test-taking skills and preparing for SATs has become part of the training that some students in these grades receive as part of their pre-college preparation. Other aptitude tests include the MCAT (Medical College Admission Test), the LSAT (Law School Admission Test), and the GRE (Graduate Record Examination). Intelligence tests are also a form of aptitude tests which are designed to measure a person’s ability to learn.

Theories of Intelligence

Intelligence tests and psychological definitions of intelligence have been heavily criticized since the 1970s for being biased in favor of Anglo-American, middle-class respondents and for being inadequate tools for measuring non-academic types of intelligence or talent. Intelligence changes with experience and intelligence quotients or scores do not reflect that ability to change. What is considered smart varies culturally as well and most intelligence tests do not take this variation into account. For example, in the West, being smart is associated with being quick. A person who answers a question the fastest is seen as the smartest. But in some cultures, being smart is associated with considering an idea thoroughly before giving an answer. A well-thought-out and contemplative answer is the best answer.

WATCH THIS video below or online to learn more about the history behind intelligence testing. You can view the transcript for “Does IQ Really Measure How Smart You Are?” here.

Multiple Intelligences

Howard Gardner (1983, 1998, 1999) suggests that there are not one, but nine domains of intelligence. His theory is known as the theory of multiple intelligences. The first three are skills that can be measured by IQ tests:

- Logical-mathematical: the ability to solve mathematical problems; problems of logic, numerical patterns

- Linguistic: vocabulary, reading comprehension, function of language

- Spatial: visual accuracy, ability to read maps, understand space and distance

The next six represent skills that are not measured in standard IQ tests but are talents or abilities that can also be important for success in a variety of fields: These are:

- Musical: ability to understand patterns in music, hear pitches, recognize rhythms and melodies

- Bodily-kinesthetic: motor coordination, grace of movement, agility, strength

- Naturalistic: knowledge of plants, animals, minerals, climate, weather

- Interpersonal: understand the emotion, mood, motivation of others; able to communicate effectively

- Intrapersonal: understanding of the self, mood, motivation, temperament, realistic knowledge of strengths, weaknesses

- Existential: concern about and understanding of life’s larger questions, meaning of life, or spiritual matters

Gardner contends that these are also forms of intelligence. A high IQ does not always ensure success in life or necessarily indicate that a person has common sense, good interpersonal skills or other abilities important for success.

Triarchic Theory of Intelligence

Another alternative view of intelligence is presented by Sternberg (1997; 1999). Sternberg offers three types of intelligences, known as the triarchic theory of intelligence. Sternberg was concerned that there was too much emphasis placed on aptitude test scores and believed that there were other, less easily measured, qualities necessary for success in a higher education and in the world of work. Aptitude test scores indicate the first type of intelligence—academic, or analytical.

- Analytical (componential): includes the ability to solve problems of logic, verbal comprehension, vocabulary, and spatial abilities.

Sternberg noted that students who have high academic abilities may still not have what is required to be a successful graduate student or a competent professional. To do well as a graduate student, he noted, the person needs to be creative. The second type of intelligence emphasizes this quality.

- Creative (experiential): the ability to apply newly found skills to novel situations.

A potential graduate student might be strong academically and have creative ideas, but still be lacking in the social skills required to work effectively with others or to practice good judgment in a variety of situations. This common sense is the third type of intelligence.

- Practical (contextual): the ability to use common sense and to know what is called for in a situation.

This type of intelligence helps a person know when problems need to be solved. Practical intelligence can help a person know how to act and what to wear for job interviews, when to get out of problematic relationships, how to get along with others at work, and when to make changes to reduce stress.

The World of School

Remember Urie Brofenbrenner’s ecological systems model we learned about when we first examined theories of development? This model helps us understand an individual by examining the contexts in which the person lives and the direct and indirect influences on that person’s life. School becomes a very important component of children’s lives during middle childhood and one way to understand children is to look at the world of school. We have discussed educational policies that impact the curriculum in schools above. Now let’s focus on the school experience from the standpoint of the student, the teacher and parent relationship, and the cultural messages or hidden curriculum taught in school in the United States.

Parents vary in their level of involvement with their children’s schools. Teachers often complain that they have difficulty getting parents to participate in their child’s education and devise a variety of techniques to keep parents in touch with daily and overall progress. For example, parents may be required to sign a behavior chart each evening to be returned to school or may be given information about the school’s events through websites and newsletters. There are other factors that need to be considered when looking at parental involvement. To explore these, first ask yourself if all parents who enter the school with concerns about their child are received in the same way? If not, what would make a teacher or principal more likely to consider the parent’s concerns? What would make this less likely?

Lareau and Horvat (2004) found that teachers seek a particular type of involvement from particular types of parents. While teachers thought they were open and neutral in their responses to parental involvement, in reality teachers were most receptive to support, praise and agreement coming from parents who were most similar in race and social class with the teachers. Parents who criticized the school or its policies were less likely to be given voice. Parents who have higher levels of income, occupational status, and other qualities favored in society have family capital. This is a form of power that can be used to improve a child’s education. Parents who do not have these qualities may find it more difficult to be effectively involved. Lareau and Horvat (2004) offer three cases of African-American parents who were each concerned about discrimination in the schools. Despite evidence that such discrimination existed, their children’s white, middle-class teachers were reluctant to address the situation directly. Note the variation in approaches and outcomes for these three families:

The Williams family: This working-class, African-American couple, a minister and a hair stylist, voiced direct complaints about discrimination in the schools. Their claims were thought to undermine the authority of the school and as a result, their daughter was kept in a lower reading class. However, her grade was boosted to “avoid a scene” and the parents were not told of this grade change.

The Irving family: This middle class, African-American couple was concerned that the school was discriminating against black students. They fought against it without using direct confrontation by staying actively involved in their daughter’s schooling and making frequent visits to the school to make sure that discrimination could not occur. They also talked with other African-American teachers and parents about their concerns.

Ms. Caldron: This poor, single-parent was concerned about discrimination in the school. She was a recovering drug addict receiving welfare. She did not discuss her concerns with other parents because she did not know the other parents and did not monitor her child’s progress or get involved with the school. She felt that her concerns would not receive attention. She requested spelling lists from the teacher on several occasions but did not receive them. The teacher complained that Ms. Caldron did not sign forms that were sent home for her signature.

Working within the system without direct confrontation seemed to yield better results for the Irvings, although the issue of discrimination in the school was not completely addressed. Ms. Caldron was the least involved and felt powerless in the school setting. Her lack of family capital and lack of knowledge and confidence keep her from addressing her concerns with the teachers. What do you think would happen if she directly addressed the teachers and complained about discrimination? Chances are, she would be dismissed as undermining the authority of the school, just as the Masons, and might be thought to lack credibility because of her poverty and drug addiction. The authors of this study suggest that teachers closely examine their biases against parents. Schools may also need to examine their ability to dialogue with parents about school policies in more open ways. What happens when parents have concerns over school policy or view student problems as arising from flaws in the educational system? How are parents who are critical of the school treated? And are their children treated fairly even when the school is being criticized? Certainly, any efforts to improve effective parental involvement should address these concerns.

Student Perspectives

Imagine being a 3rd-grader for one day in public school. What would the daily routine involve? To what extent would the institution dictate the activities of the day and how much of the day would you spend on those activities? Would you always be on task? What would you say if someone asked you how your day went? or “What happened in school today?” Chances are, you would be more inclined to talk about whom you sat at lunch with or who brought a puppy to class than to describe how fractions are added.

Ethnographer and Professor of Education Peter McLaren (1999) describes the student’s typical day as filled with constrictive and unnecessary ritual that has a damaging effect on the desire to learn. Students move between various states as they negotiate the demands of the school system and their own personal interests. The majority of the day (298 minutes) takes place in the student state. This state is one in which the student focuses on a task or tries to stay focused on a task, is passive, compliant, and often frustrated. Long pauses before getting out the next book or finding materials sometimes indicate that frustration. The street corner state is one in which the child is playful, energetic, excited, and expresses personal opinions, feelings, and beliefs. About 66 minutes a day take place in this state. Children try to maximize this by going slowly to assemblies or when getting a hall pass-always eager to say ‘hello’ to a friend or to wave if one of their classmates is in another room. This is the state in which friends talk and play. In fact, teachers sometimes reward students with opportunities to move freely or to talk or to be themselves. But when students initiate the street corner state on their own, they risk losing recess time, getting extra homework, or being ridiculed in front of their peers. The home state occurs when parents or siblings visit the school. Children in this state may enjoy special privileges such as going home early or being exempt from certain school rules in the mother’s presence, or it can be difficult if the parent is there to discuss trouble at school with a staff member. The sanctity state is a time in which the child is contemplative, quiet, or prayerful. Typically, the sanctity state is a very brief part of the day.

Since students seem to have so much enthusiasm and energy in street corner states, what would happen if the student and street corner states could be combined? Would it be possible? Many educators feel concern about the level of stress children experience in school. Some stress can be attributed to problems in friendship. And some can be a result of the emphasis on testing and grades, as reflected in a Newsweek article entitled “The New First Grade: Are Kids Getting Pushed Too Fast Too Soon?” (Tyre, 2006). This article reports concerns of a principal who worries that students begin to burn out as early as 3rd grade. In the book, The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing, Kohn (2006) argues that neither research nor experience support claims that homework reinforces learning and builds responsibility. Why do schools assign homework so frequently? A look at cultural influences on education may provide some answers.

Cultural Influences

Another way to examine the world of school is to look at the cultural values, concepts, behaviors and roles that are part of the school experience but are not part of the formal curriculum. These are part of the hidden curriculum but are nevertheless very powerful messages. The hidden curriculum includes ideas of patriotism, gender roles, the ranking of occupations and classes, competition, and other values. Teachers, counselors, and other students specify and make known what is considered appropriate for girls and boys. The gender curriculum continues into high school, college, and professional school. Students learn a ranking system of occupations and social classes as well. Students in gifted programs or those moving toward college preparation classes may be viewed as superior to those who are receiving tutoring.

Gracy (2004) suggests that cultural training occurs early. Kindergarten is an “academic boot camp” in which students are prepared for their future student role-that of complying with an adult imposed structure and routine designed to produce docile, obedient, children who do not question meaningless tasks that will become so much of their future lives as students. A typical day is filled with structure, ritual, and routine that allows for little creativity or direct, hands-on contact. “Kindergarten, therefore, can be seen as preparing children not only for participation in the bureaucratic organization of large modern school systems, but also for the large-scale occupational bureaucracies of modern society.” (Gracy, 2004, p. 148)

Emphasizing math and reading in preschool and kindergarten classes is becoming more common in some school districts. It is not without controversy, however. Some suggest that emphasis is warranted in order to help students learn math and reading skills that will be needed throughout school and in the world of work. This will also help school districts improve their accountability through test performance. Others argue that learning is becoming too structured to be enjoyable or effective and that students are being taught only to focus on performance and test-taking. Students learn student incivility or lack of sincere concern for politeness and consideration of others is taught in kindergarten through 12th grades through the “what is on the test” mentality modeled by teachers. Students are taught to accept routinized, meaningless information in order to perform well on tests. And they are experiencing the stress felt by teachers and school districts focused on test scores and taught that their worth comes from their test scores. Genuine interest, an appreciation of the process of learning, and valuing others are important components of success in the workplace that are not part of the hidden curriculum in today’s schools.

Across the world, by the time a child is entering middle childhood, they are being educated in some form or fashion. In western society, most children are enrolled in a formal education program by the time they are in middle childhood. That said, what children learn within that formal education program varies greatly across cultures. Further, most programs are set-up for typically developing children, but they may not be set-up to handle children who are accelerated learners or children with learning disabilities. In this section, we’ll take a look at some of these educational differences and developments, as well as struggles and learning difficulties during middle childhood.

Children’s cognitive and social skills are evaluated as they enter and progress through school. Sometimes this evaluation indicates that a child needs special assistance with language or in learning how to interact with others. Evaluation and diagnosis of a child can be the first step in helping to provide that child with the type of instruction and resources needed. But diagnosis and labeling also have social implications. It is important to consider that children can be misdiagnosed and that once a child has received a diagnostic label, the child, teachers and family members may tend to interpret actions of the child through that label. The label can also influence the child’s self-concept. Consider, for example, a child who is misdiagnosed as learning disabled. That child may expect to have difficulties in school, lack confidence, and out of these expectations, have trouble indeed. This self-fulfilling prophecy, or tendency to act in such a way as to make what you predict will happen, comes true, and calls our attention to the power that labels can have whether or not they are accurately applied.

It is also important to consider that children’s difficulties can change over time; a child who has problems in school may improve later or may live under circumstances as an adult where the problem (such as a delay in math skills or reading skills) is no longer relevant. That person, however, will still have a label as learning disabled. It should be recognized that the distinction between abnormal and normal behavior is not always clear; some abnormal behavior in children is fairly common. Misdiagnosis may be more of a concern when evaluating learning difficulties than in cases of autism spectrum disorder where unusual behaviors are clear and consistent.

Keeping these cautionary considerations in mind, let’s turn our attention to some developmental and learning difficulties.

Developmental and Learning Difficulties

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Diego is always active, from the time he wakes up in the morning until the time he goes to bed at night. His mother reports that he came out the womb kicking and screaming, and he has not stopped moving since. He has a sweet disposition, but always seems to be in trouble with his teachers, parents, and after-school program counselors. Diego seems to accidentally break things constantly, he lost his jacket three times last winter, and he never seems to sit still. His teachers believe Diego is a smart child, but he never finishes anything he starts and is so impulsive that he does not seem to learn much in school.

Diego likely has attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The symptoms of this disorder were first described by Hans Hoffman in the 1920s. While taking care of his son while his wife was in the hospital giving birth to a second child, Hoffman noticed that the boy had trouble concentrating on his homework, had a short attention span, and had to repeatedly go over easy homework to learn the material. Later, it was discovered that many hyperactive children—those who are fidgety, restless, socially disruptive, and have trouble with impulse control—also display short attention spans, problems with concentration, and distractibility. By the 1970s, it had become clear that many children who display attention problems often also exhibit signs of hyperactivity. In recognition of such findings, the DSM-3 (published in 1980) included a new disorder: attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity, now known as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

A child with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) shows a constant pattern of inattention and/or hyperactive and impulsive behavior that interferes with normal functioning (APA, 2013). Some of the signs of inattention include great difficulty with and avoidance of tasks that require sustained attention (such as conversations or reading), failure to follow instructions (often resulting in failure to complete schoolwork and other duties), disorganization (difficulty keeping things in order, poor time management, and sloppy and messy work), lack of attention to detail, becoming easily distracted, and forgetfulness. Hyperactivity is characterized by excessive movement and includes fidgeting or squirming, leaving one’s seat in situations when remaining seated is expected, having trouble sitting still (e.g., in a restaurant), running about and climbing on things, blurting out responses before another person’s question or statement has been completed, difficulty waiting one’s turn for something, and interrupting and intruding on others. Frequently, the hyperactive child comes across as noisy and boisterous. The child’s behavior is hasty, impulsive, and seems to occur without much forethought; these characteristics may explain why adolescents and young adults diagnosed with ADHD receive more traffic tickets and have more automobile accidents than do others (Thompson, Molina, Pelham, & Gnagy, 2007).

ADHD occurs in about 5% of children (APA, 2013). On the average, boys are three times more likely to have ADHD than are girls; however, such findings might reflect the greater propensity of boys to engage in aggressive and antisocial behavior and thus incur a greater likelihood of being referred to psychological clinics (Barkley, 2006). This may also be reflective of bias in failing to appropriately diagnose girls and women who show symptoms. Children with ADHD face severe academic and social challenges. Compared to their non-ADHD counterparts, children with ADHD have lower grades and standardized test scores and higher rates of expulsion, grade retention, and dropping out (Loe & Feldman, 2007). They also are less well-liked and more often rejected by their peers (Hoza et al., 2005).

Previously, ADHD was thought to fade away by adolescence. However, longitudinal studies have suggested that ADHD is a chronic problem, one that can persist into adolescence and adulthood (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2002). A recent study found that 29.3% of adults who had been diagnosed with ADHD decades earlier still showed symptoms (Barbaresi et al., 2013). Somewhat troubling, this study also reported that nearly 81% of those whose ADHD persisted into adulthood had experienced at least one other comorbid disorder compared to 47% of those whose ADHD did not persist.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is considered a neurological and behavioral disorder in which a person has difficulty staying on task, screening out distractions, and inhibiting behavioral outbursts. The most commonly recommended treatment involves the use of medication, structuring the classroom environment to keep distractions at a minimum, tutoring, and teaching parents how to set limits and encourage age-appropriate behavior (NINDS, 2006). Some people say that the term Attention Deficit is a misnomer because people who suffer from ADHD actually have great difficulty tuning things out. They are bombarded with information… their brains are trying to pay attention to everything. They do not have a deficit of attention- they are trying to pay attention to too many things at once, so everything suffers.

Life Problems from ADHD

Children diagnosed with ADHD face considerably worse long-term outcomes than do those children who do not receive such a diagnosis. In one investigation, 135 adults who had been identified as having ADHD symptoms in the 1970s were contacted decades later and interviewed. Compared to a control sample of 136 participants who had never been diagnosed with ADHD, those who were diagnosed as children

- had worse educational attainment (more likely to have dropped out of high school and less likely to have earned a bachelor’s degree);

- had lower SES;

- held less prestigious occupational positions;

- were more likely to be unemployed;

- made considerably less in salary;

- scored worse on a measure of occupational functioning, indicating, for example, lower job satisfaction, poorer work relationships, and more firings;

- scored worse on a measure of social functioning, indicating, for example, fewer friendships and less involvement in social activities;

- were more likely to be divorced; and

- were more likely to have non-alcohol-related substance abuse problems

Longitudinal studies also show that children diagnosed with ADHD are at higher risk for substance abuse problems. One study reported that childhood ADHD predicted later drinking problems, daily smoking, and use of marijuana and other illicit drugs. The risk of substance abuse problems appears to be even greater for those with ADHD who also exhibit antisocial tendencies.

Causes of ADHD

Family and twin studies indicate that genetics play a significant role in the development of ADHD. Burt (2009), in a review of 26 studies, reported that the median rate of concordance for identical twins was 0.66 (one study reported a rate of 0.90), whereas the median concordance rate for fraternal twins was 0.20. This study also found that the median concordance rate for unrelated (adoptive) siblings was 0.09; although this number is small, it is greater than zero, thus suggesting that the environment may have at least some influence. Another review of studies concluded that the heritability of inattention and hyperactivity were 71% and 73%, respectively (Nikolas & Burt, 2010).

The specific genes involved in ADHD are thought to include at least two that are important in the regulation of the neurotransmitter dopamine (Gizer, Ficks, & Waldman, 2009), suggesting that dopamine may be important in ADHD. Indeed, medications used in the treatment of ADHD, such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) and amphetamine with dextroamphetamine (Adderall), have stimulant qualities and elevate dopamine activity. People with ADHD show less dopamine activity in key regions of the brain, especially those associated with motivation and reward (Volkow et al., 2009), which provides support to the theory that dopamine deficits may be a vital factor in the development this disorder (Swanson et al., 2007).

Brain imaging studies have shown that children with ADHD exhibit abnormalities in their frontal lobes, an area in which dopamine is in abundance. Compared to children without ADHD, those with ADHD appear to have smaller frontal lobe volume, and they show less frontal lobe activation when performing mental tasks. Recall that one of the functions of the frontal lobes is to inhibit our behavior. Thus, abnormalities in this region may go a long way toward explaining the hyperactive, uncontrolled behavior of ADHD.

By the 1970s, many had become aware of the connection between nutritional factors and childhood behavior. At the time, much of the public believed that hyperactivity was caused by sugar and food additives, such as artificial coloring and flavoring. Undoubtedly, part of the appeal of this hypothesis was that it provided a simple explanation of (and treatment for) behavioral problems in children. A statistical review of 16 studies, however, concluded that sugar consumption has no effect at all on the behavioral and cognitive performance of children (Wolraich, Wilson, & White, 1995).

Additionally, although food additives have been shown to increase hyperactivity in non-ADHD children, the effect is rather small (McCann et al., 2007). Numerous studies, however, have shown a significant relationship between exposure to nicotine in cigarette smoke during the prenatal period and ADHD (Linnet et al., 2003). Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with the development of more severe symptoms of the disorder (Thakur et al., 2013).

Is ADHD caused by poor parenting? Not likely. Remember, the genetics studies discussed above suggested that the family environment does not seem to play much of a role in the development of this disorder; if it did, we would expect the concordance rates to be higher for fraternal twins and adoptive siblings than has been demonstrated. All things considered, the evidence seems to point to the conclusion that ADHD is triggered more by genetic and neurological factors and less by social or environmental ones.

READ THIS How is ADHD diagnosed? The DSM-V lists the criteria that must be present in order for a diagnosis to be made and an official diagnosis must be made by a qualified mental health professional. It is also important to note that the term ADD is an older term that has been phased out in the newer versions of the DSM. Review the criteria for ADHD. Do you think that making a diagnosis would be difficult? Why or why not?

Treatment of ADHD

The management of ADHD typically involves psychotherapy or medications either alone or in combination. While treatment may improve long-term outcomes, it does not get rid of negative outcomes entirely. Stimulant medications are the pharmaceutical treatment of choice. Stimulants have at least some effect on symptoms: in the short term, in about 80% of people. While this may seem counter-intuitive (why give a hyperactive child a stimulant?), when you understand the neurological processes involved, it makes a lot of sense. There are two ways that stimulants may work to help people with ADHD focus. Some researchers have found that the stimulants activate the underdeveloped parts of the brain (prefontal cortex and frontal lobe) thereby making these brain areas function more as they should. This allows the child or adult to focus properly. Other researchers suspect that the stimulants affect the way the neurotransmitters function in these brain areas, leading to better function in those areas. ADHD stimulants also improve persistence and task performance in children with ADHD.

There is still a lot of controversy about medicating children with ADHD. While there is clear evidence that medication works to control the negative effects of ADHD, there are also negative side effects that must be dealt with including problems sleeping, changes in appetite, headaches, and more. Further, the long-term effects of medicating young children are not well understood. For these reasons, many parents prefer an intervention that does not involve medication. Psychological therapies used include the following: psychoeducational input, behavior therapy, CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy, family therapy, school-based interventions, social skills training, behavioral peer intervention, organization training, parent management training, and neurofeedback. Training in social skills, behavioral modification, and medication may have some limited beneficial effects. The most important factor in reducing later psychological problems, such as major depression, criminality, school failure, and substance use disorders, is the formation of friendships with people who are not involved in delinquent activities.

The most common non-pharmaceutical intervention for ADHD is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). CBT works by helping children to become aware of their thought processes, and then to learn to change those thought processes to be more beneficial or positive. CBT can also help by educating parents about ways to help their children learn about self-control and discipline. There is very good evidence that CBT is an effective strategy in treating ADHD. Indeed, in some studies, children treated with CBT have better long-term outcomes than children treated with medication.

Some studies show that a combination of medication and CBT is most beneficial because the medication helps with behavior change more quickly, allowing for the child to learn through CBT more quickly. The CBT then helps with longer-term behavior change so that the child can stop taking medications and deal effectively with their ADHD symptoms based on what they have learned through CBT.

Regular physical exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, is an effective add-on treatment for ADHD in children and adults, particularly when combined with stimulant medication, although the best intensity and type of aerobic exercise for improving symptoms are not currently known. In particular, the long-term effects of regular aerobic exercise in ADHD individuals include better behavior and motor abilities, improved executive functions (including attention, inhibitory control, and planning, among other cognitive domains), faster information processing speed, and better memory. Parent-teacher ratings of behavioral and socio-emotional outcomes in response to regular aerobic exercise include better overall function, reduced ADHD symptoms, better self-esteem, reduced levels of anxiety and depression, fewer somatic complaints, better academic and classroom behavior, and improved social behavior.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder is a neurodevelopmental disorder in which severity differs from person to person and affects communication and behavior. The estimate published by the Center for Disease Control (2018) is that about 1 out of every 54 children in the United States has been diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), which covers a wide variety of ranges in ability, from those with milder forms (formerly known as Asperger’s Syndrome) to more severe deficits in communication. ASD is four times more prevalent in males than females.

READ THIS Learn more about Autism Spectrum Disorders at the Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

A person with autism often has difficulty with language. An autistic child may respond to a question by repeating the question or might rarely speak. Sometimes autistic children learn more difficult words before simple words or can complete complicated tasks before they are able to complete easier ones. A child with ASD may have difficulty reading social cues such as the meanings of non-verbal gestures such as a wave of the hand or the emotion associated with a frown. Intense sensitivity to touch or visual stimulation may also be experienced. They often have poor social skills and are often unable to communicate with others or empathize with others emotionally. People with autism often view the world differently and learn differently than people who do not have an autism spectrum disorder. Children with autism tend to prefer routines and patterns and become upset when routines are altered. For example, moving the furniture or changing the daily schedule can be very upsetting. Because it is a spectrum disorder, some people with ASD are very functional and have good-to-excellent language skills. Many of these people do not feel that they suffer from a disorder and instead believe that they just process information differently.

Many children with ASD are not identified until they reach school age, although the ability to diagnose children earlier continues to improve. In the 2017-2018 school year, about 710,000 children on the spectrum received special education through public schools. These disorders are found in all racial and ethnic groups and have been thought to be more common in boys than in girls, though new research is evolving. All of these disorders are marked by difficulty in social interactions, problems in various areas of communication, and in difficulty with altering patterns or daily routines.

There is no single cause of ASD and the causes of these disorders are to a large extent, unknown. In cases involving identical twins, if one twin has autism, the other also has ASD about 75 percent of the time. Rubella, fragile X syndrome and PKU that has been untreated are some of the medical conditions associated with the risks of autism. At a general level, ASD is thought to be a disease of “incorrect” wiring. Accordingly, brains of some ASD patients lack the same level of synaptic pruning that occurs in non-affected people. There has been some unsubstantiated controversy linking vaccinations and autism. In the 1990s, a research paper linked autism to a common vaccine given to children. This paper was retracted when it was discovered that the author falsified data; follow-up studies showed no connection between vaccines and autism.

Some individuals benefit from medications that alleviate some of the symptoms of ASD, but the most effective treatments involve behavioral intervention and teaching techniques used to promote the development of language and social skills. Children also excel when they are in structured learning environments that accommodate the needs of children on the spectrum.

WATCH THIS video below or online to learn more about how better diagnosis and awareness are behind the increased rates of autism, rather than vaccines:

Neurodiversity

The autism rights movement promotes the concept of neurodiversity, which views autism as a natural variation of the brain rather than a disorder to be cured. In response to the rising idea that autism (and other similar disorders) are an epidemic, the concept of neurodiversity shines a new perspective on the subject.

Coined in 1998 by Australian sociologist Judy Singer, who helped popularize the concept along with American journalist Harvey Blume, neurodiversity emerged as a challenge to prevailing views that certain neurodevelopmental disorders are inherently pathological and instead adopts the social model of disability, in which societal barriers are the main contributing factor that disables people. The term represented a move away from previous “mother-blaming” theories about the cause of autism.

Neurodiversity advocates point out that neurodiverse people often have exceptional abilities alongside their weaknesses. For example, a person with ADHD may hyperfocus on some tasks while struggling to focus on others, or an autistic person may have exceptional memory or even savant skills. In light of these facts, advocates argue for recognition of strengths as well as weaknesses in neurodiverse people, and that a variety of neurological conditions that are currently classified as disorders are better regarded as differences. This view is especially popular within the autism rights movement.

Neurodiversity advocates denounce the framing of autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other neurodevelopmental disorders as requiring medical intervention to “cure” or “fix” them and instead promote support systems, such as inclusion-focused services, accommodations, communication, and assistive technologies, occupational training, and independent living support. The intention is for individuals to receive support that honors authentic forms of human diversity, self-expression, and being, rather than treatment that coerces or forces them to adopt normative ideas of normality or to conform to a clinical ideal. Proponents of neurodiversity strive to reconceptualize autism and related conditions in society by the following measures: acknowledging that neurodiversity does not require a cure; changing the language from the current “condition, disease, disorder, or illness”-based nomenclature, and “broaden[ing] the understanding of healthy or independent living”; acknowledging new types of autonomy; and giving non-neurotypical individuals more control over their treatment, including the type, timing, and whether there should be treatment at all.

However, the neurodiversity paradigm has been controversial among disability advocates, with opponents saying that its conceptualization doesn’t reflect the realities of individuals who have high-support needs.

Learning Disabilities

What is a learning disability? If a child has an intellectual disability, or intellectual development disorder, they will have significant impairment in intellectual and adaptive functioning, generally defined by an IQ under 70 (two standard deviations below the median), in addition to deficits in two or more adaptive behaviors that affect everyday, general living. A child with intellectual development disorder typically learns slowly in all areas of learning.

However, a child with a learning disability has problems in a specific area or with a specific task or type of activity related to education. It should be pointed out that learning disabilities are not the same thing as intellectual disabilities. Learning disabilities are considered specific neurological impairments rather than global intellectual or developmental disabilities. These are identified in the Diagnostic and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as a specific learning disorder. A learning difficulty refers to a deficit in a child’s ability to perform an expected academic skill (Berger, 2005). These difficulties are identified in school because this is when children’s academic abilities are being tested, compared, and measured. Consequently, once academic testing is no longer essential in that person’s life (as when they are working rather than going to school) these disabilities may no longer be noticed or relevant, depending on the person’s job and the extent of the disability.

Dyslexia

Dyslexia, sometimes called reading disorder, is the most common learning disability; of all students with specific learning disabilities, 70–80% have deficits in reading. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. The term developmental dyslexia is often used as a catch-all term, but researchers assert that dyslexia is just one of several types of reading disabilities. A reading disability can affect any part of the reading process, including word recognition, word decoding, reading speed, prosody (oral reading with expression), and reading comprehension. For example, a child may reverse letters, may have difficulty reading from left to right, or may have problems associating letters with sounds. Dyslexia appears to be rooted in some neurological problems involving the parts of the brain active in recognizing letters, verbally responding, or being able to manipulate sounds (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2006). Treatment typically involves altering teaching methods to accommodate the person’s particular problematic area.

WATCH THIS video below or online where reading expert Margie Gillis explains dyslexia. You can view the transcript for “What Is Dyslexia? | Dyslexia Explained” here.

TRY THIS short Dyslexia simulation below or online with captions meant to show some of the ways dyslexia can present:

Dyscalculia

Dyscalculia is a form of math-related disability that involves difficulties with learning math-related concepts (such as quantity, place value, and time), memorizing math-related facts, organizing numbers, and understanding how problems are organized on the page. People with this dyscalculia are often referred to as having poor “number sense.”

Dysgraphia

The term dysgraphia is often used as an overarching term for all disorders of written expression. Individuals with dysgraphia typically show multiple writing-related deficiencies, such as grammatical and punctuation errors within sentences, poor paragraph organization, multiple spelling errors, and excessively poor penmanship.

Social Development

Now let’s turn our attention to concerns related to social development, self-concept, the world of friendships, and family life. During middle childhood, children are likely to show more independence from their parents and family, think more about the future, understand more about their place in the world, pay more attention to friendships, and want to be accepted by their peers.

Freud’s Psychosexual Development: The Latency Stage

Remember that Freud’s theory of psychosexual development suggests that children develop their personality through a series of psychosexual stages. In each stage, the erogenous zone is the source of the libidinal energy. So far we have seen the oral stage (ages birth – 18 months), the anal stage (ages 18 months – 3 years), and the phallic stage (ages 3 years – 6 years).

During middle childhood (6-11), the child enters the latency stage, focusing their attention outside the family and toward friendships. Freud’s fourth stage of psychosexual development is the latency stage. This stage begins around age 6 and lasts until puberty. The biological drives are temporarily quieted (latent) and the child can direct attention to a larger world of friends. If the child is able to make friends, they will gain a sense of confidence. If not, the child may continue to be a loner or shy away from others, even as an adult.

In the latency stage, children are actually doing very little psychosexual developing according to Freud. Where pleasure and development occurred through erogenous zones in the first 3 stages, in the latency stage all pleasure from erogenous zones is repressed. In other words, it is latent—hence the stage’s name. Freud believed that in the latency stage all development and stimulation come from secondary sources since the erogenous forces are repressed. These secondary sources can include education, forming various social relationships, and hobbies.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Development: Industry vs. Inferiority

As we have seen in previous modules, Erikson believes that children’s greatest source of personality development comes from their social relationships. So far, we have seen 3 psychosocial stages: trust versus mistrust (ages birth – 18 months), autonomy versus shame and doubt (ages 18 months – 3 years), and initiative versus guilt (ages 3 years – around 6 years).