3 Module 3: Psychological and Developmental Theories

Module 3 Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner will be able to:

- Define Developmental Theories

Explain what developmental theories are and how they help us understand human growth across the lifespan, including their strengths and weaknesses. - Compare Key Psychoanalytic and Psychosocial Theories

Summarize Freud’s psychosexual theory and Erikson’s psychosocial stages, identifying their significance, real-life applications, and limitations in understanding psychology and human growth. - Explore Behavioral and Social Learning Theories

Describe the principles of classical and operant conditioning, as well as Bandura’s social learning theory, using real-life examples of how behaviors are shaped and modeled. - Analyze Cognitive and Sociocultural Development

Compare Piaget’s stages of cognitive development with Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, emphasizing their importance in understanding how learning and interaction with others contribute to human growth. - Examine Motivation Theories

Describe and compare key motivational theories, such as the theory of planned behavior, locus of control, SMART goal-setting, stages of change, and terror management theory, and analyze their relevance to understanding behavior in healthcare and other settings. - Apply Ecological Systems and Family Systems Theories

Describe Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model and family systems theory, analyzing how direct and indirect environmental influences shape an individual’s development and behavior. - Explore Evolutionary Perspectives

Explain the principles of evolutionary psychology, including how adaptations have shaped universal behaviors, and their relevance to understanding lifespan development. - Discuss Behavioral Genetics

Explain gene-environment interactions, including range of reaction, genetic-environmental correlation, and epigenetics, and analyze examples from behavioral genetics research to understand the interplay of nature and nurture. - Understand the Role of Hormones in Behavior

Describe the structure and function of the endocrine system, including major glands and hormones, and their influence on behavior and regulation of bodily functions. - Evaluate Strengths and Limitations of Theories

Compare and contrast key psychological and developmental theories, highlighting their significance in understanding psychology and human growth, as well as their limitations. - Examine Contextual Influences on Development

Analyze how cultural, environmental, and societal factors interact with biological and psychological processes to shape behavior and development. - Interpret Applications in Healthcare

Use developmental and motivational theories to analyze and interpret behaviors relevant to healthcare settings, such as patient adherence, coping strategies, and wellness planning.

Introduction

In this chapter, we will start to examine theories of human development. As discussed in chapter one, human development describes the growth throughout their lifespan, from conception to death. Psychologists strive to understand and explain how and why people change throughout life. We will see that different theories cover different aspects of growth — like how we think, process and remember information changes across the lifespan. Much of what is covered in developmental theory is what expected, typical growth is. Some of the theories presented in this chapter are considered classic theories that have now been debated. They are still taught for historical purposes, and each holds important underlying concepts to understanding others. We will first cover the basics of what a theory is and then review several major theories in human development.

What is a Theory?

Students sometimes feel intimidated by theory; even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories . . .” is met with blank stares and other indications that the audience is now lost. However, theories are valuable tools for understanding human behavior; in fact, they are proposed explanations for the “how” and “whys” of development. Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3-year-old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders rejected by their classmates?” Theories can help explain these and other occurrences. Developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time and the kinds of influences that impact development.

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other objects that required assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more quickly than if trial and error are used.

Theories can be developed using induction in which several single cases are observed, and after patterns or similarities are noted, the theorist develops ideas based on these examples. Established theories are then tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are difficult to test but are still useful in stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical application. Keep in mind that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them.

We will start with the earlier theories of development and work our way to newer ones.

What lies beneath: Psychoanalytic theories

Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

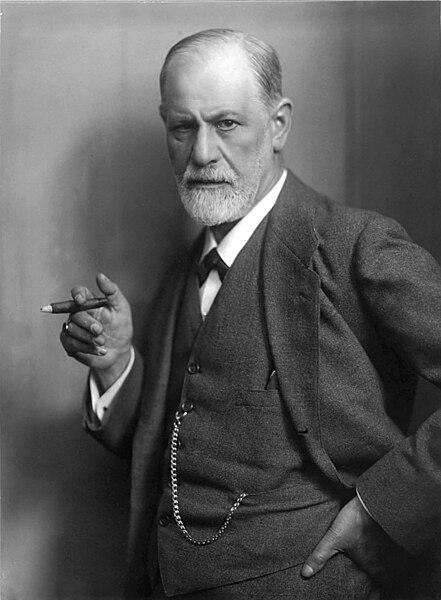

Let’s begin with the often-controversial figure, Sigmund Freud. Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was a Viennese M. D. who was trained in neurology and asked to work with patients suffering from hysteria, a condition marked by uncontrollable emotional outbursts, fears, and anxiety that had puzzled physicians for centuries. Freud began working with hysterical patients and discovered that when they began to talk about some of their life experiences, particularly those that took place in early childhood, their symptoms disappeared. This led him to suggest the first purely psychological explanation for physical problems and mental illness. What he proposed was that unconscious motives and desires, fears and anxieties drive our actions.

His assumptions about development were that personality forms during the first few years of life and that how parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resiliency in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady & Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Most psychologists do not agree with all, or even most, of Freud’s theory but do agree that our early experiences can provide a foundation for how we approach later experiences.

Freud’s theory of self

Freud’s theory of self suggests that there are three parts of the self.

The id is the part of the self that is inborn. It responds to biological urges without pause and is guided by the principle of pleasure: if it feels good, it is the thing to do. A newborn is all id. The newborn cries when hungry, defecates when the urge strikes.

The ego develops through interaction with others and is guided by logic or the reality principle. It has the ability to delay gratification. It knows that urges have to be managed. It mediates between the id and superego using logic and reality to calm the other parts of the self.

The superego represents society’s demands for its members. It is guided by a sense of guilt. Values, morals, and the conscience are all part of the superego.

READ THIS if you are interested for a more in-depth overview of the components of Freud’s theory.

Psychosexual Stages

Freud’s psychosexual stages of development are presented below. At any of these stages, the child might become “stuck” or fixated if a caregiver either overly indulges or neglects the child’s needs. A fixated adult will continue to try and resolve this later in life. Examples of fixation are given after the presentation of each stage.

Table: Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory |

|

|

Name of Stage |

Descriptions of Stage |

|

Oral Stage |

The oral stage lasts from birth until around age 2. At this stage all stimulation and comfort is focused on the mouth and is based on the reflex of sucking. Too much indulgence or too little stimulation may lead to fixation. |

|

Anal Stage |

The anal stage coincides with potty training or learning to manage biological urges. Anal fixation may result in a person who is compulsively clean and organized or one who is sloppy and lacks self-control. |

|

Phallic Stage |

The phallic stage occurs in early childhood and marks the development a sense of masculinity or femininity as culture dictates. |

|

Latency |

Latency occurs during middle childhood when a child’s urges quiet down and friendships become the focus. The child learns how to cooperate and negotiate with others. |

|

Genital Stage |

The genital stage begins with puberty and continues through adulthood. Now the preoccupation is that of sex and reproduction. |

For about the first year of life, the infant is in the oral stage of psychosexual development. The infant meets needs primarily through oral gratification. A baby wishes to suck or chew on any object that comes close to the mouth. Babies explore the world through the mouth and find comfort and stimulation as well. Psychologically, the infant is all Id. The infant seeks immediate gratification of needs such as comfort, warmth, food, and stimulation. If the caregiver meets oral needs consistently, the child will move away from this stage and progress further. However, if the caregiver is inconsistent or neglectful, the person may stay stuck in the oral stage. As an adult, the person might not feel good unless involved in some oral activity such as eating, drinking, smoking, nail-biting, or compulsive talking. These actions bring comfort and security when the person feels insecure, afraid, or bored.

During the anal stage which coincides with toddlerhood or mobility and potty-training, the child is taught that some urges must be contained and some actions postponed. There are rules about certain functions and when and where they are to be carried out. The child is learning a sense of self-control. The ego is being developed. If the caregiver is extremely controlling about potty training (stands over the child waiting for the smallest indication that the child might need to go to the potty and immediately scoops the child up and places him on the potty chair, for example), the child may grow up fearing losing control. He may become fixated in this stage or “anal retentive”-fearful of letting go. Such a person might be extremely neat and clean, organized, reliable, and controlling of others. If the caregiver neglects to teach the child to control urges, he may grow up to be “anal expulsive” or an adult who is messy, irresponsible, and disorganized.

The Phallic stage occurs during the preschool years (ages 3-5) when the child has a new biological challenge to face. Freud believed that the child becomes sexually attracted to his or her opposite sexed parent. Boys experience the “Oedipal Complex” in which they become sexually attracted to their mothers but realize that Father is in the way. He is much more powerful. For awhile, the boy fears that if he pursues his mother, father may castrate him (castration anxiety). So rather than risking losing his penis, he gives up his affections for his mother and instead learns to become more like his father, imitating his actions and mannerisms and thereby learns the role of males in his society. From this experience, the boy learns a sense of masculinity. He also learns what society thinks he should do and experiences guilt if he does not comply. In this way, the superego develops. If he does not resolve this successfully, he may become a “phallic male” or a man who constantly tries to prove his masculinity (about which he is insecure) by seducing women and beating up men! A little girl experiences the “Electra Complex” in which she develops an attraction for her father but realizes that she cannot compete with mother and so gives up that affection and learns to become more like her mother. This is not without some regret, however. Freud believed that the girl feels inferior because she does not have a penis (experiences “penis envy”). But she must resign herself to the fact that she is female and will just have to learn her inferior role in society as a female. However, if she does not resolve this conflict successfully, she may have a weak sense of femininity and grow up to be a “castrating female” who tries to compete with men in the workplace or in other areas of life.

During middle childhood (6-11), the child enters the latent stage focusing his or her attention outside the family and toward friendships. The biological drives are temporarily quieted (latent) and the child can direct attention to a larger world of friends. If the child is able to make friends, he or she will gain a sense of confidence. If not, the child may continue to be a loner or shy away from others, even as an adult.

The final stage of psychosexual development is referred to as the genital stage. From adolescence throughout adulthood a person is preoccupied with sex and reproduction. The adolescent experiences rising hormone levels and the sex drive and hunger drives become very strong. Ideally, the adolescent will rely on the ego to help think logically through these urges without taking actions that might be damaging. An adolescent might learn to redirect their sexual urges into safer activity such as running, for example. Quieting the Id with the Superego can lead to feeling overly self-conscious and guilty about these urges. Hopefully, it is the ego that is strengthened during this stage and the adolescent uses reason to manage urges.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is challenging to test scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature and suggests that much of what determines our actions is unknown to us. So why do we study Freud? As mentioned above, despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework from which elaborates and modifies subsequent theories of development. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, were challenges to Freud’s views.

What motivates growth: Psychosocial theory

Now, let’s turn to a less controversial psychodynamic theorist, the father of developmental psychology, Erik Erikson.

Erik Erikson (1902-1994) was a student of Freud’s and expanded on his theory of psychosexual development by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968). He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the Id. We make conscious choices in life, and these choices focus on meeting specific social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems. Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages. In each stage, we have a primary psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living.

Psychosocial Stages

Erikson described eight stages, each with a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our life span as we face these challenges. We will discuss each of these stages in greater detail when we discuss each of these life stages throughout the course. Here is an overview of each stage:

Trust vs. Mistrust (Hope)—From birth to 12 months of age, infants must learn that adults can be trusted. This occurs when adults meet a child’s basic needs for survival. Infants are dependent upon their caregivers, so caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust; their baby will see the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can engender feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust; their baby may see the world as unpredictable. If infants are treated cruelly or their needs are not met appropriately, they will likely grow up with a sense of mistrust for people in the world.

Autonomy vs. Shame (Will)—As toddlers (ages 1–3 years) begin to explore their world, they learn that they can control their actions and act on their environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy vs. shame and doubt by working to establish independence. This is the “me do it” stage. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a 2-year-old child who wants to choose her clothes and dress herself. Although her outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, her input in such basic decisions has an effect on her sense of independence. If denied the opportunity to act on her environment, she may begin to doubt her abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.

Initiative vs. Guilt (Purpose)—Once children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. According to Erikson, preschool children must resolve the task of initiative vs. guilt. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master this task. Initiative, a sense of ambition and responsibility, occurs when parents allow a child to explore within limits and then support the child’s choice. These children will develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage—with their initiative misfiring or stifled by over-controlling parents—may develop feelings of guilt.

Industry vs. Inferiority (Competence)—During the elementary school stage (ages 7–12), children face the task of industry vs. inferiority. Children begin to compare themselves with their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate because they feel that they don’t measure up. If children do not learn to get along with others or have negative experiences at home or with peers, an inferiority complex might develop into adolescence and adulthood.

Identity vs. Role Confusion (Fidelity)—In adolescence (ages 12–18), children face the task of identity vs. role confusion. According to Erikson, an adolescent’s main task is developing a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit; they explore various roles and ideas, set goals, and attempt to discover their adult selves. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. When adolescents are apathetic, do not make a conscious search for identity, or are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future, they may develop a weak sense of self and experience role confusion. They will be unsure of their identity and confused about the future. Teenagers who struggle to adopt a positive role will likely struggle to find themselves as adults.

Intimacy vs. Isolation (Love)—People in early adulthood (20s through early 40s) are concerned with intimacy vs. isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, we are ready to share our life with others. However, if other stages have not been successfully resolved, young adults may have trouble developing and maintaining successful relationships with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before we can develop successful intimate relationships. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

Generativity vs. Stagnation (Care)—When people reach their 40s, they enter the time known as middle adulthood, which extends to the mid-60s. The social task of middle adulthood is generativity vs. stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. During this stage, middle-aged adults begin contributing to the next generation, often through caring for others; they also engage in meaningful and productive work which contributes positively to society. Those who do not master this task may experience stagnation and feel as though they are not leaving a mark on the world in a meaningful way; they may have little connection with others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.

Integrity vs. Despair (Wisdom)—From the mid-60s to the end of life, we are in the period of development known as late adulthood. Erikson’s task at this stage is called integrity vs. despair. He said that people in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity, and they can look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” and “could have” been. They may face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.

|

Stage |

Approximate Age (years) |

Virtue: Developmental Task |

Description |

|

1 |

0–1 |

Hope: Trust vs. Mistrust |

Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

|

2 |

1–3 |

Will: Autonomy vs. Shame |

Sense of independence in many tasks develops |

|

3 |

3–6 |

Purpose: Initiative vs. Guilt |

Take initiative on some activities, may develop guilt when success not met or boundaries overstepped |

|

4 |

7–11 |

Competence: Industry vs. Inferiority |

Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

|

5 |

12–18 |

Fidelity: Identity vs. Role Confusion |

Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

|

6 |

19–39 |

Love: Intimacy vs. Isolation |

Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

|

7 |

40–64 |

Care: Generativity vs. Stagnation |

Contribute to society and be part of a family |

|

8 |

65+ |

Wisdom: Integrity vs. Despair |

Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Strengths and weaknesses of Erikson’s theory

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is prerequisite for the next crisis of development. Like Freud’s theory, it has been criticized for focusing more on men than women and also for its vagueness, making it difficult to test rigorously. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices.

WATCH THIS video below or view online to learn more about Erikson’s stages:

What we do: Behavioral Theories

Behaviorism

While Freud and Erikson looked at what was going on in the mind, behaviorism rejected any reference to mind and viewed overt and observable behavior as the proper subject matter of psychology. Through the scientific study of behavior, it was hoped that laws of learning could be derived that would promote the prediction and control of behavior.

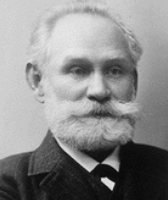

Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Pavlov (1880-1937) was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they actually began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. “This,” he thought, “is not natural!” One would expect a dog to automatically salivate when food hit their palate, but BEFORE the food comes? Of course, what had happened was . . . you tell me. That’s right! The dogs knew that the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The key word here is “learned”. A learned response is called a “conditioned” response.

Pavlov began to experiment with this concept of classical conditioning. He began to ring a bell, for instance, prior to introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell. Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus. The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon, a conditioned response. Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned) and one is learned (conditioned).

Let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist, John B. Watson.

John B. Watson

John B. Watson (1878-1958) believed that most of our fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He had gained a good deal of popularity in the 1920s with his expert advice on parenting offered to the public.

He tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18-month-old boy named “Little Albert”. Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to him: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. But Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears is the fear of loud noises so he proceeded to make a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favorites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise several times paired with the rat, Albert soon came to fear the rat and began to cry when it was introduced. Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any outcomes they desired, if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and in magazines and gained a lot of popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order.

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, looks at the way the consequences of a behavior increase or decrease the likelihood of a behavior occurring again. So let’s look at this a bit more.

B.F. Skinner and Operant Conditioning

B. F. Skinner (1904-1990), who brought us the principles of operant conditioning, suggested that reinforcement is a more effective means of encouraging a behavior than is criticism or punishment. By focusing on strengthening desirable behavior, we have a greater impact than if we emphasize what is undesirable. Reinforcement is anything that an organism desires and is motivated to obtain.

A reinforcer is something that encourages or promotes a behavior. Some things are natural rewards. They are considered intrinsic or primary because their value is easily understood. Think of what kinds of things babies or animals such as puppies find rewarding.

Extrinsic or secondary reinforcers are things that have a value not immediately understood. Their value is indirect. They can be traded in for what is ultimately desired.

The use of positive reinforcement involves adding something to a situation in order to encourage a behavior. For example, if I give a child a cookie for cleaning a room, the addition of the cookie makes cleaning more likely in the future. Think of ways in which you positively reinforce others.

Negative reinforcement occurs when taking something unpleasant away from a situation encourages behavior. For example, I have an alarm clock that makes a very unpleasant, loud sound when it goes off in the morning. As a result, I get up and turn it off. By removing the noise, I am reinforced for getting up. How do you negatively reinforce others?

Punishment is an effort to stop a behavior. It means to follow an action with something unpleasant or painful. Punishment is often less effective than reinforcement for several reasons. It doesn’t indicate the desired behavior, it may result in suppressing rather than stopping a behavior, (in other words, the person may not do what is being punished when you’re around, but may do it often when you leave), and a focus on punishment can result in not noticing when the person does well. Not all behaviors are learned through association or reinforcement. Many of the things we do are learned by watching others. This is addressed in social learning theory.

Many people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment in operant conditioning, but they are two very different mechanisms. Remember that reinforcement, even when it is negative, always increases a behavior. In contrast, punishment always decreases a behavior. In positive punishment, you add an undesirable stimulus to decrease a behavior. An example of positive punishment is scolding a student to get the student to stop texting in class. In this case, a stimulus (the reprimand) is added in order to decrease the behavior (texting in class). In negative punishment, you remove a pleasant stimulus to decrease a behavior. For example, taking away a video game or placing a child in a time out for fighting with their sibling is negative punishment; you remove something the child likes (games, attention) to decrease the undesirable behavior (fighting).

Punishment, especially when it is immediate, is one way to decrease undesirable behavior. For example, imagine your four-year-old son, Brandon, runs into the busy street to get his ball. You give him a time-out (negative punishment) and tell him never to go into the street again. Chances are he won’t repeat this behavior. While strategies like time-outs are common today, in the past children were often subject to physical punishment, such as spanking. It’s important to be aware of some of the drawbacks in using physical punishment on children. First, punishment may teach fear. If you spanked Brandon and caused pain to him when he ran in the street, Brandon may become fearful of the street, but he also may become fearful of the person who delivered the punishment—you, his parent. Similarly, children who are physically punished by teachers may come to fear the teacher and try to avoid school (Gershoff et al., 2010). Consequently, most schools in the United States have banned corporal punishment. Second, physical punishment may cause children to become more aggressive and prone to antisocial behavior and delinquency (Gershoff, 2002). They see their parents resort to spanking when they become angry and frustrated, so, in turn, they may act out this same behavior when they become angry and frustrated. For example, because you spank Brenda when you are angry with her for her misbehavior, she might start hitting her friends when they won’t share their toys.

While punishment can be effective, and needed, in some cases, Skinner suggested that the use of punishment should be weighed against the possible negative effects. Today’s psychologists and parenting experts favor reinforcement over punishment—they recommend that you catch your child doing something good and reward her for it.

Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura (1925-2021) is a leading contributor to social learning theory. He calls our attention to the ways in which many of our actions are not learned through conditioning; rather, they are learned by watching others (1977). Young children frequently learn behaviors through imitation.

Sometimes, particularly when we do not know what else to do, we learn by modeling or copying the behavior of others. A kindergartner on his or her first day of school might eagerly look at how others are acting and try to act the same way to fit in more quickly. Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to act as role-models. Sometimes we do things because we’ve seen it pay off for someone else. They were operantly conditioned, but we engage in the behavior because we hope it will pay off for us as well. This is referred to as vicarious reinforcement (Bandura, Ross and Ross, 1963).

Bandura (1986) suggests that there is interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings, rather we influence our surroundings. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently with their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along they have very different expectations both of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us and we create our environment.

Bandura and the Bobo Doll Experiment & Today’s Children and the Media

Bandura (et al. 1963) began a series of studies to look at the impact of television, particularly commercials, on the behavior of children. Are children more likely to act out aggressively when they see this behavior modeled? What if they see it being reinforced? Bandura began by conducting an experiment in which he showed children a film of a woman hitting an inflatable clown or “bobo” doll. Then the children were allowed in the room where they found the doll and immediately began to hit it. This was without any reinforcement whatsoever. Not only that, but they found new ways to behave aggressively. It’s as if they learned an aggressive role.

Children view far more television today than in the 1960s; so much, in fact, that they have been referred to as Generation M (media). The amount of screen time varies by age. As of 2017, children 0-8 spend an average of 2 hours and 19 minutes. Children 8-12 years of age spend almost 6 hours a day on screen media. And 13- to 18-year-olds spend an average of just under 9 hours a day in entertainment media use.

The prevalence of violence, sexual content, and messages promoting foods high in fat and sugar in the media are certainly cause for concern and the subjects of ongoing research and policy review. Many children spend even more time on the computer viewing content from the internet. The amount of time spent connected to the internet continues to increase with the use of smartphones that essentially serve as mini-computers. And the ways children and adolescents interact with the media continues to change. The popularity of YouTube and the various social media platforms are examples of this.

What might be the implications of this?

What We Think: Cognitive Theories

Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

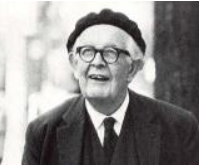

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) is one of the most influential cognitive theorists. Piaget was inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out the ways in which children’s thought differs from that of adults. His interest in this area began when he was asked to test the IQ of children and began to notice that there was a pattern in their wrong answers. He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time through maturation. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Piaget believed our desire to understand the world comes from a need for cognitive equilibrium. This is an agreement or balance between what we sense in the outside world and what we know in our minds. If we experience something that we cannot understand, we try to restore the balance by either changing our thoughts or by altering the experience to fit into what we do understand. Perhaps you meet someone who is very different from anyone you know. How do you make sense of this person? You might use them to establish a new category of people in your mind or you might think about how they are similar to someone else.

A schema or schemes are categories of knowledge. They are like mental boxes of concepts. A child has to learn many concepts. They may have a scheme for “under” and “soft” or “running” and “sour”. All of these are schema. Our efforts to understand the world around us lead us to develop new schema and to modify old ones.

One way to make sense of new experiences is to focus on how they are similar to what we already know. This is assimilation. The person we meet who is very different may be understood as being “sort of like my brother” or “his voice sounds a lot like yours.” Or a new food may be assimilated when we determine that it tastes like chicken!

Another way to make sense of the world is to change our mind. We can make a cognitive accommodation to this new experience by adding new schema. This food is unlike anything I’ve tasted before. I now have a new category of foods that are bitter-sweet in flavor, for instance. This is accommodation. Do you accommodate or assimilate more frequently? Children accommodate more frequently as they build new schema. Adults tend to look for similarity in their experience and assimilate. They may be less inclined to think “outside the box.” Piaget suggested different ways of understanding that are associated with maturation. He divided this into four stages:

Table: Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development |

|

|

Name of Stage |

Description of Stage |

|

Sensorimotor Stage |

During the sensorimotor stage children rely on use of the senses and motor skills. From birth until about age 2, the infant knows by tasting, smelling, touching, hearing, and moving objects around. This is a real hands on type of knowledge. |

|

Preoperational Stage |

In the preoperational stage, children from ages 2 to 7, become able to think about the world using symbols. A symbol is something that stands for something else. The use of language, whether it is in the form of words or gestures, facilitates knowing and communicating about the world. This is the hallmark of preoperational intelligence and occurs in early childhood. However, these children are preoperational or pre-logical. They still do not understand how the physical world operates. They may, for instance, fear that they will go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub, even though they are too big. |

|

Concrete Operational |

Children in the concrete operational stage, ages 7 to 11, develop the ability to think logically about the physical world. Middle childhood is a time of understanding concepts such as size, distance, and constancy of matter, and cause and effect relationships. A child knows that a scrambled egg is still an egg and that 8 ounces of water is still 8 ounces no matter what shape of glass contains it. |

|

Formal Operational |

During the formal operational stage children, at about age 12, acquire the ability to think logically about concrete and abstract events. The teenager who has reached this stage is able to consider possibilities and to contemplate ideas about situations that have never been directly encountered. More abstract understanding of religious ideas or morals or ethics and abstract principles such as freedom and dignity can be considered. |

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget has been criticized for overemphasizing the role that physical maturation plays in cognitive development and in underestimating the role that culture and interaction (or experience) plays in cognitive development. Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children are able to do at various ages. Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances.

Lev Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s. Vygotsky differed with Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development. His belief was that development occurred first through children’s immediate social interactions, and then moved to the individual level as they began to internalize their learning.

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you all through the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do-you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen demonstrated throughout the world. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern day educators.

Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky

Vygotsky concentrated more on the child’s immediate social and cultural environment and his or her interactions with adults and peers. While Piaget saw the child as actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it, Vygotsky saw the child as more of an apprentice, learning through a social environment of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities.

Psychological Theories of Motivation and Behavior Important in Healthcare

Theory of Planned Behavior

An individual’s intentions to voluntarily behave in a particular way are most immediately determined by their intentions to do so. For example, getting someone to meditate will, at a bare minimum, require them to intend to meditate. One key issue within persuasion is therefore to determine what influences behavioral intentions. The Theory of Reasoned Action, and its extension the Theory of Planned Behavior, are commonly used theories of persuasion that explain what variables predict behavioral intentions.

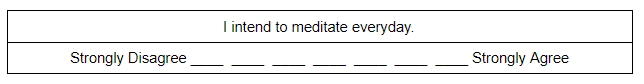

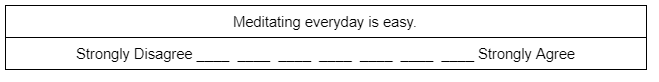

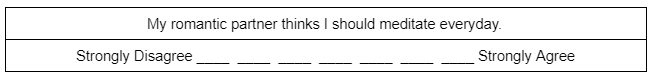

The Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) posits that behavior is directly determined by an individual’s behavioral intentions. In other words, as an individual’s intentions to perform a behavior increase, they are more likely to actually perform the behavior. Behavioral intentions are oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

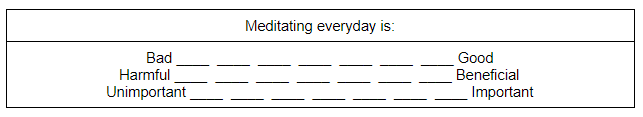

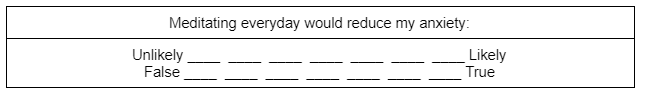

The Theory of Reasoned Action posits that intentions are directly predicted by (1) an individual’s attitude towards the behavior and (2) subjective norms. An attitude is defined as an individual’s evaluation of a given behavior. Someone might have a positive, negative, or neutral attitude about a given behavior. As an individual’s attitude becomes more positive, their intentions to perform a behavior will increase. Attitudes are oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

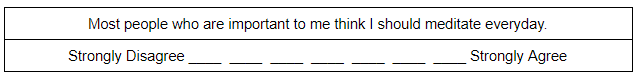

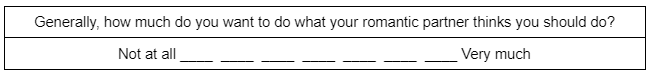

Subjective norms are defined as an individual’s beliefs about the importance others place on them performing a given behavior. In other words, it is the degree to which an individual perceives that other people want them to engage in the behavior. As an individual’s subjective norms increase, their intentions to perform a behavior will increase. Subjective norms are oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

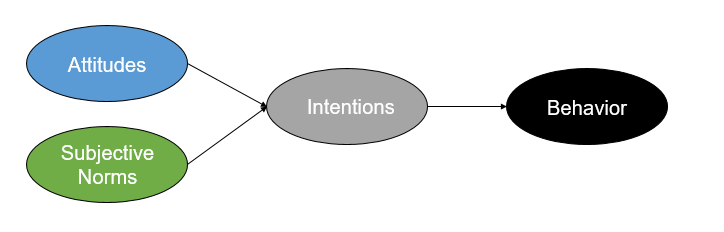

The Theory of Reasoned Action is depicted below:

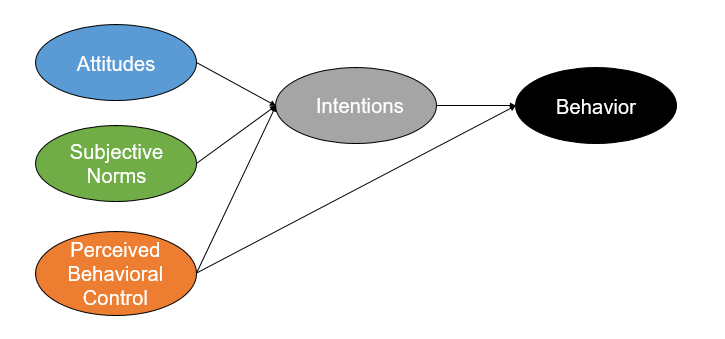

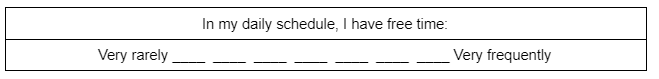

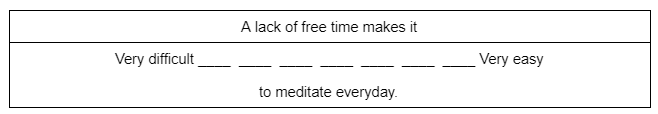

The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1988, 1991) extends the Theory of Reasoned Action by including perceived behavioral control. The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that a behavior is directly determined by an individual’s intentions and perceived behavioral control. Perceived behavioral control, also referred to as self-efficacy, encompasses the extent to which an individual believes they have control over performing that behavior. Intentions, in turn, are directly predicted by (1) an individual’s attitude towards the behavior, (2) subjective norms, and (3) perceived behavioral control. Perceived behavioral control is oftentimes assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

The Theory of Planned Behavior is depicted below:

How are the predictors weighted in the Theory of Planned Behavior?

Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control do not always contribute equally to predicting intentions. Sometimes, an individual’s intentions may be determined largely by attitudes, and subjective norms may have little or no influence. Other times, an individual’s intentions may be determined largely by subjective norms, and attitudes may have little or no influence. For example, college students’ intentions to meditate may largely be driven by their attitudes that meditating everyday is good, beneficial, and important; whether or not other people think they should meditate may not influence their intentions as strongly. The only way to determine the relative importance of (or weighting) of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control on intentions is to measure these variables across a group of study participants and run a statistical analysis.

What influences the relationship between intentions and behavior?

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that intentions lead to behavior; however, intentions do not always guarantee behavior. For example, someone might intend to meditate everyday but not follow through. There are several factors that influence the strength of the relationship between intentions and behavior.

First, the Theory of Planned Behavior underscores a principle of specificity. This means that in order to best predict behavior, the attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control beliefs must relate to specific intentions and a subsequent specific behavior. These frameworks note that any given behavior includes an action, target, context and time period. For example, a goal might be “to meditate for 20 minutes before bed each day in the upcoming month.” In this example, “meditating” is the action, “20 minutes” is the target, “before bed each day” is the context, and “in the upcoming month” is the time period. As the specificity of the behavior increases, intentions become a better predictor of behavior.

Additionally, the temporal stability of intentions influences the strength of the relationship between intentions and behavior. If an individual’s intentions fluctuate over time (e.g., some days I intend to meditate, and other days I do not), then intentions measured at one particular time might not predict subsequent behavior (e.g., Rhodes & Dickau, 2013). As the stability of an individual’s intentions increases over time, intentions become a better predictor of behavior.

What additional predictors have been examined in the Theory of Planned Behavior?

The Theory of Planned Behavior focuses on rational reasoning and excludes the role of emotional and subconscious influences (see, e.g., Sniehotta, Presseau, & Araújo-Soares, 2014). Scholars have argued for the importance of these variables and have therefore suggested that anticipated emotions and past, habitual behaviors should be added to the Theory of Planned Behavior to better predict intentions and subsequent behavior.

People anticipate the emotions they will experience after performing a particular behavior — for example, an individual might anticipate feeling regret, guilt, or pride if they do or do not perform a given behavior. Anticipated emotions can therefore shape and motivate behaviors as people strive to avoid negative feelings and attain positive feelings (Baumeister, Vohs, DeWall, & Zhan 2007; O’Keefe, 2065). Past research has found that anticipated emotions have added to the explanatory power of the Theory of Planned Behavior for predicting, for example, cancer screening (McGilligan, McClenahan, & Adamnson, 2009), vaccination (Gallagher & Povey, 2006), seat belt use (Şimşekoğlu & Lajunen), caregiving behaviors (Tracy & Robins, 2004), bone marrow donation (Lindsey, Yun, & Hill, 2007), and organ donor registration (Wang, 2011).

Specific anticipated emotions that have been studied include anticipated regret, guilt, and pride. For example, one meta-analysis found that anticipated regret added significantly and independently to the prediction of both intentions and prospective behavior over and above Theory of Planned Behavior variables (Sandberg & Conner, 2008). Past research also notes that people will avoid actions that they anticipate will make them feel guilty. Thus anticipated guilt serves as an important predictor of intentions (O’Keefe, 2002). Finally, anticipated pride can impact intentions and behaviors, specifically for behaviors that conform to social standards and prosocial behaviors (Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007; Tracey & Robins, 2004).

Past behavior can have a significant influence on future behavior, specifically when the past behavior is habitual or routine (Ouellette & Wood, 1998; Sniehotta, 2014). This habitual behavior is oftentimes automatic instead of fully intentional and thus can influence intentions themselves or directly influence behavior by sidestepping intentions. As the behavior becomes more habitual, the relationship between past behavior and future behavior increases. Past research has found this to be the case for, for example, cancer screening (Norman & Cooper, 2011), riding a bicycle (de Bruijn & Gardner, 2011), eating behaviors (de Bruijn, 2010; de Bruijn, Kroeze, Oenema, & Brug, 2008), exercise (de Bruijn & Rhodes, 2010), and alcohol consumption (Norman & Conner, 2006).

How can the Theory of Planned Behavior be used to create persuasive messages?

The Theory of Planned Behavior specifies that it is possible to change someone’s intentions by influencing one or more of the three determinants of intentions (attitudes, subjective norms, and/or perceived behavioral control).

Attitudes

An individual’s attitude towards a given behavior could be influenced in a number of different ways. The Theory of Planned Behavior specifies the determinants of attitudes, which are useful to identify specific strategies to do so.

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that an individual’s attitudes towards a given behavior are a joint function of their evaluation of each belief about the behavior and the strength with which each belief is held. The strength of a belief can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

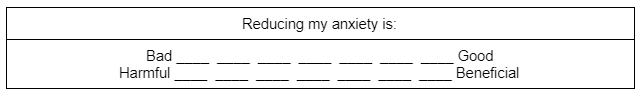

The evaluation of each belief can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

Changing an individual’s attitudes could therefore be achieved by changing the evaluation of an existing salient belief. This might involve increasing the salience of an existing negative belief (e.g., “You probably already know that anxiety can be harmful, but you may not realize just how consequential it really can be””) or decreasing the salience of an existing positive belief (e.g., “Maybe you think your anxiety helps motivate you to complete your work, but there are other ways to accomplish your tasks”).

Changing an individual’s attitudes could also be achieved by changing the strength of an existing salient belief. This might involve increasing the belief strength of an existing positive belief (e.g, “You probably already know that meditation can reduce anxiety, but maybe you don’t realize just how likely it is to decrease”) or decreasing the belief strength of an existing positive belief (e.g., “Anxiety won’t actually motivate you to complete your work”).

Finally, changing an individual’s attitudes could be achieved by adding a new salient belief. This can be accomplished by providing the individual with additional information about the behavior and outcome of interest (e.g., “You might not realize that anxiety can increase your risk of heart disease”).

Subjective Norms

An individual’s subjective norms about a given behavior could be influenced in a number of different ways. The Theory of Planned Behavior specifies the determinants of subjective norms, which are useful to identify specific strategies to do so.

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that an individual’s subjective norms about a given behavior are a joint function of their evaluation of normative beliefs that they ascribe to important others and their motivation to comply with those others. An individual’s normative beliefs can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

The motivation to comply with those important others can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

Changing an individual’s subjective norms could therefore be accomplished by increasing the salience of a particular referent (e.g., “Have you considered whether your girlfriend thinks it is important for you to decrease your anxiety and meditate everyday?”), changing the normative belief associated with a specific reference (e.g., “You’re actually wrong – I talked to your girlfriend, and she thinks you should meditate everyday to decrease your anxiety”), or altering the motivation to comply with a current referent (e.g., “You should really consider what she thinks about this”).

Perceived Behavioral Control

An individual’s perceived behavioral control for a given behavior could be influenced in a number of different ways. The Theory of Planned Behavior specifies the determinants of perceived behavioral control, which are useful to identify specific strategies to do so.

The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that an individual’s perceived behavioral control for a given behavior are a joint function of their assessment of the likelihood or frequency that a specific control factor will occur and the potential for the control factor to impede or facilitate the behavior. An individual’s assessment of the likelihood or frequency that a given control factor will occur can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

The potential for the control factor to impede or facilitate the behavior can be assessed with a questionnaire. An example is shown here:

Changing an individual’s perceived behavioral control can be accomplished in many ways. The persuader could directly remove the obstacle, create the opportunity for successful performance of the given behavior (e.g., “I’ve done it before, so I can do it again”), provide examples of others who have successfully performed the behavior (e.g., “If they can do it, I can do it”), or provide verbal encouragement (e.g., “You can do it!”; O’Keefe, 2016). Any of these strategies individually, or concurrently, could influence an individual’s assessment of the control factor, thus positively influencing their perceived behavioral control.

Transtheoretical Model (Stages of Change)

The transtheoretical model of behavior change, developed by Prochaska and DiClemente, assesses an individual’s readiness to implement a healthier behavior, and provides insight into the decision making process that leads to action. For many people, changing or modifying a behavior that is unhealthy or potentially harmful can be quite challenging. Here are the stages that lead to behavior change:

Precontemplation (Not Ready) – You are not intending to take action in the foreseeable future, and can be unaware that your behavior is problematic

Contemplation (Getting Ready) – You are beginning to recognize that your behavior is problematic, and start to look at the pros and cons of your continued actions

Preparation (Ready) – You are intending to take action in the immediate future, and may begin taking small steps toward behavior change

Action – You are making actual changes to your problem behavior by incorporating healthy choices/behaviors into your life

Maintenance – You have been able to sustain action for at least six months and are working to prevent relapse into previous unhealthy behaviors

WATCH THIS video below or view online with captions to review the main concepts of the Transtheoretical Model:

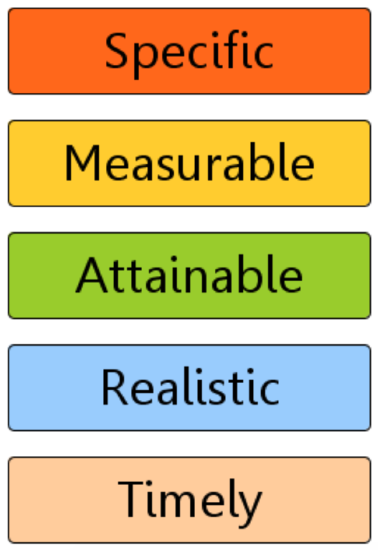

SMART Goal Setting

Have you ever said to yourself that you need to “eat healthier” or “exercise more” to improve your overall health? How well did that work for you? In most cases, probably not very well. That’s because these statements are too vague and do not give us any direction for what truly needs to be done to achieve such goals. To have a better chance at being successful, try using the SMART acronym for setting your goals (S= Specific, M= Measurable, A=Attainable, R= Realistic, T= Time-oriented):

Specific – Create a goal that has a focused and clear path for what you actually need to do. Examples:

I will drink 8 ounces of water 3 times per day

I will walk briskly for 30 minutes, 5 times per week

I will reduce my soda intake to no more than 2 cans of soda per week

Do you see how that is more helpful than just saying you will eat healthier or exercise more? It gives you direction.

Measurable – This enables you to track your progress, and ties in with the “specific” component. The above examples all have actual numbers associated with the behavior change that let you know whether or not it has been met.

Attainable – Make sure that your goal is within your capabilities and not too far out of reach. For example, if you have not been physically active for a number of years, it would be highly unlikely that you would be able to achieve a goal of running a marathon within the next month.

Realistic – Try to ensure that your goal is something you will be able to continue doing and incorporate as part of your regular routine/lifestyle. For example, if you made a goal to kayak 2 times each week, but don’t have the financial resources to purchase or rent the equipment, no way to transport it, or are not close enough to a body of water in which to partake in kayaking, then this is not going to be feasible.

Time-oriented – Give yourself a target date or deadline in which the goal needs to be met. This will keep you on track and motivated to reach the goal, while also evaluating your progress.

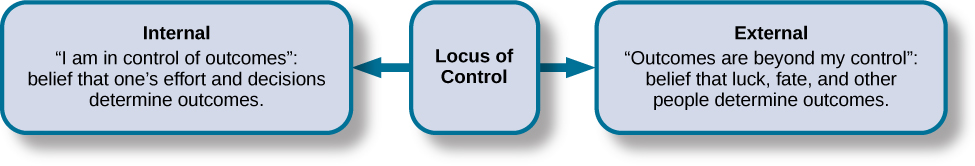

Locus of Control

Julian Rotter (1966) proposed the concept of locus of control, another cognitive factor that affects learning and personality development. Distinct from self-efficacy, which involves our belief in our own abilities, locus of control refers to our beliefs about the power we have over our lives. In Rotter’s view, people possess either an internal or an external locus of control. Those of us with an internal locus of control (“internals”) tend to believe that most of our outcomes are the direct result of our efforts. Those of us with an external locus of control (“externals”) tend to believe that our outcomes are outside of our control. Externals see their lives as being controlled by other people, luck, or chance. For example, say you didn’t spend much time studying for your psychology test and went out to dinner with friends instead. When you receive your test score, you see that you earned a D. If you possess an internal locus of control, you would most likely admit that you failed because you didn’t spend enough time studying and decide to study more for the next test. On the other hand, if you possess an external locus of control, you might conclude that the test was too hard and not bother studying for the next test, because you figure you will fail it anyway. Researchers have found that people with an internal locus of control perform better academically, achieve more in their careers, are more independent, are healthier, are better able to cope, and are less depressed than people who have an external locus of control (Benassi, Sweeney, & Durfour, 1988; Lefcourt, 1982; Maltby, Day, & Macaskill, 2007; Whyte, 1977, 1978, 1980).

TAKE THIS If you are interested, you can take the Locus of Control questionnaire. Scores range from 0 to 13. A low score on this questionnaire indicates an internal locus of control, and a high score indicates an external locus of control.

Terror Management Theory

READ THIS article by Psychologyfanatic.com to learn about Terror Management Theory

Contextual Theories: Going beyond the Individual

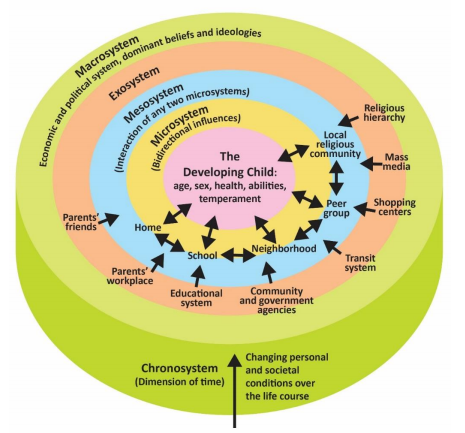

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development. Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all of those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model explains the direct and indirect influences on an individual’s development.

Table: Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model |

|

|

Name of System |

Description of System |

|

Microsystems |

Microsystems impact a child directly. These are the people with whom the child interacts such as parents, peers, and teachers. The relationship between individuals and those around them need to be considered. For example, to appreciate what is going on with a student in math, the relationship between the student and teacher should be known. |

|

Mesosystems |

Mesosystems are interactions between those surrounding the individual. The relationship between parents and schools, for example will indirectly affect the child. |

|

Exosystem |

Larger institutions such as the mass media or the healthcare system are referred to as the exosystem. These have an impact on families and peers and schools who operate under policies and regulations found in these institutions. |

|

Macrosystems |

We find cultural values and beliefs at the level of macrosystems. These larger ideals and expectations inform institutions that will ultimately impact the individual. |

|

Chronosystem |

All of this happens in an historical context referred to as the chronosystem. Cultural values change over time, as do policies of educational institutions or governments in certain political climates. Development occurs at a point in time. |

For example, in order to understand a student in math, we can’t simply look at that individual and what challenges they face directly with the subject. We have to look at the interactions that occur between teacher and child. Perhaps the teacher needs to make modifications as well. The teacher may be responding to regulations made by the school, such as new expectations for students in math or constraints on time that interfere with the teacher’s ability to instruct. These new demands may be a response to national efforts to promote math and science deemed important by political leaders in response to relations with other countries at a particular time in history.

Family as Social Context: Family Systems Theory

The family system is a powerful source of environmental influence to consider.

Family forms a context for a great deal of human development—it is a site where individuals learn behaviors through operant conditioning (reinforcement and punishment of their behaviors) and observational learning (behavioral models), as well as become socialized into their culture, social norms, and social roles. The physical environment established by a family can also influence development and behavior through constraints and opportunities provided to individuals. Family social relationships influence a person’s motivation for social conformity or deviance, as well. Family can be a source of stress or a source of resilience and protective factors.

Family Systems Theory claims that the family is understood best by conceptualizing it as a complex, dynamic, and changing collection of parts, subsystems and family members. Much like a mechanic would interface with the computer system of a broken-down car to diagnose which systems are broken (transmission, electric, fuel, etc.) to repair it, a therapist or researcher would interact with family members to diagnose how and where the systems of the family are working and where they are in need of repair or intervention.

In the article entitled, “Understanding Families: Applying Family Systems Theory to Early Childhood Practice” by Linda Garris Christian, she states that family systems theory can explain why members of a family behave the way they do in a given situation. She identifies the six characteristics that make up the theory collectively.

The six characteristics are:

Boundaries – relates to limit, togetherness and separateness—what or who is “in” or “out of” the family.

Roles – in all families individuals members have roles, those roles may include – peacemaker, clown, rescuer, victim, these roles can be carried over into work, school, and social settings.

Rules – a set of standards, laws, or traditions that tell us how-to live-in relation to each other, they are often embedded in a cultural context; therefore, they can contribute to the feeling of cultural discontinuity that some children experience at school.

Hierarchy – this refers to who holds the decision making, control, and power in the family, each time the family composition changes, there is a shift in where family members are in their hierarchy.

Climate – this is about the emotional and physical environment of the family.

Equilibrium – the refers to the balance or imbalance that exists in the family, consistency in families can be difficult to maintain, but it is critical to children’s development that they have a sense of security and trust to maintain healthy development

Below is more information about Family Systems Theory and how families impact development and behavior.

The family is a system embedded in other, larger social systems. Just as we saw the individual embedded in micro- to macro-level systems in the social ecological framework, family systems also are embedded in progressively larger social systems. We cannot hope to understand families or their behavior, functioning, and development without understanding their interactions with their ecological contexts—the influences of extended family, neighborhood, social institutions, culture, society, and large-scale political, economic, and historical trends. Individuals are not only a product of (and influence on) interactions with the nuclear family but also of the family’s interactions with extended family—how might extended kin relationships impact the behaviors of an individual family member?

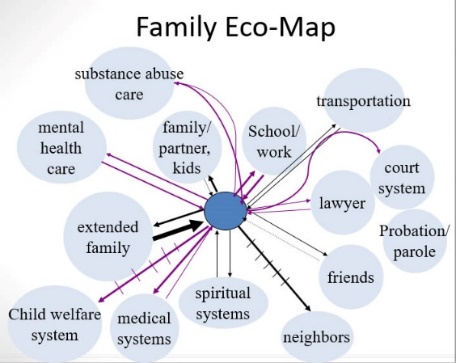

An eco-map is a visual assessment tool (originally described by Dr. Ann Hartmann) used in social work to help families identify and express the nature and quality of their interactions with the surrounding systems—what is supportive and what is detrimental, where the energy, emotional, and resource “costs” to the family are excessive compared to what is gained, and where the “gains” are more favorable than the costs. In some cases, a family eco-map may appear overly sparse, leaving the family under-resourced and socially isolated. At the other extreme, a family’s eco-map may be overly saturated with formal institutions that serve the family but at a high “cost” in effort and energy. Even if the amount and types of ecological relationships may be reasonably balanced, the qualitative picture may be heavily conflict-ridden as opposed to working peacefully or harmoniously. For example, when a family member engages in substance misuse involvement with criminal justice, child welfare, housing, and health care systems may occur, much of which is demanding despite possibly providing needed resources. All of this relates to the degree of stress which the family system is under in its day-to-day existence.

2. The family system is greater than the sum of its parts. “The family” has meaning to its members separate from what each individual family member might mean. A family has an identity and “life” of its own. In many instances, family members act to further the family’s interests, even at individual expense.

3. Family systems are comprised of subsystems. Family systems do not always operate as a whole; many interactions, roles, and functions are enacted within subsystems of the larger family system. These might include a couple subsystem, parent-child subsystems, or sibling subsystems. The possible variants are numerous especially when ex-partner, step-parent, step-/half-sibling, and extended family subsystems are involved.

4. Change in any part of the system affects the entire system. Family systems are dynamic, changing over time as recognized in the chromosphere aspect of the social ecological model—past, present, and future look different because families are not static or stagnant. It is important to remember that all change—positive and negative in nature—are experienced as stressful, challenging the family system’s hard-earned balance. Consider, for example, how stressful happy family development events like marriage, childbirth, and retirement can be for the system; this adaptive pressure might bewilder families who only expected to be stressed by negative changes such as divorce or the death of a family member. Family system changes are a response to pressures from the outside (contexts), family membership, internal subsystems, and changes in individuals. Some pressures are developmental in nature—the dynamics of parenting young children may be very different from parenting adolescents, for example. It is the nature of systems that change in any part of the family system reverberates throughout the entire family system, sending ripples throughout the system.

Evolutionary and Biological Theories: Inside the Individual

Evolutionary Psychology

Evolutionary psychology focuses on how universal patterns of behavior and cognitive processes have evolved over time. Variations in cognition and behavior would make individuals more or less successful in reproducing and passing those genes to their offspring. Evolutionary psychologists study a variety of psychological phenomena that may have evolved as adaptations, including the fear response, food preferences, mate selection, and cooperative behaviors (Confer et al., 2010).

Many think of evolution as the development of traits and behaviors that allow us to survive this “dog-eat-dog” world, like strong leg muscles to run fast, or fists to punch and defend ourselves. However, physical survival is only important if it eventually contributes to successful reproduction. That is, even if you live to be 100 years old, if you fail to mate and produce children, your genes will die with your body. Thus, reproductive success, not survival success, is the engine of evolution by natural selection.

Charles Darwin describes this process in the theory of evolution by natural selection. In simple terms, the theory states that organisms that are better suited for their environment will survive and reproduce, while those that are poorly suited for their environment will die off. There is a growing interest in applying the principles of evolutionary psychology to better understand lifespan development in humans.

Lifespan Development and Evolutionary Psychology

As we consider development from conception through the lifespan, there will be many opportunities to understand how evolutionary psychology enhances our understanding of development. For instance, women and men do differ in their preferences for a few key qualities in long-term mating, because of somewhat distinct adaptive concerns. Modern women have inherited the evolutionary trait to desire mates who possess resources, have qualities linked with acquiring resources (e.g., ambition, wealth, industriousness), and are willing to share those resources with them. On the other hand, men more strongly desire youth and health in women, as both are cues to fertility. These male and female differences have historically been universal in humans.

Just because a psychological adaptation was advantageous in our history, doesn’t mean it’s still useful today. For example, even though women may have preferred men with resources in previous generations, our modern society has advanced such that these preferences are no longer necessary. Nonetheless, it’s important to consider how our evolutionary history has shaped our automatic or “instinctual” desires and reflexes of today so that we can better shape them for the future ahead.

As we follow the journey of life, from conception to death, think about how the theory of natural selection and the concepts of evolutionary psychology can enlighten our understanding of why some automatic reflexes or instinctual desires are more common than others. Remember that the end product of the theory of evolution by natural selection is successful survival and reproduction. Can you think of some ways that the ultimate goal of reproductive success affects our selection of a mate, how we parent young children, why we are motivated to achieve certain goals, or what differentiates families with traditionally longer lifespans? In order to achieve reproductive success, the theory of evolution by natural selection states that organisms should be suited to their environment. Think about how different environments or cultures require different traits for successful survival and reproduction. Can you think of some ways that we may be changing to be better suited to our changing culture?

WATCH THIS David Buss is one of the leading researchers in evolutionary psychology. Watch his TED TALK below or online with captions where he explains several theories related to the selection of sexual partners, mating preferences, and infidelity:

Behavioral Genetics

Behavioral geneticists study how individual differences arise, in the present, through the interaction of genes and the environment. When studying human behavior, behavioral geneticists often employ twin and adoption studies to research questions of interest. Twin studies compare the rates that a given behavioral trait is shared among identical and fraternal twins; adoption studies compare those rates among biologically related relatives and adopted relatives. Both approaches provide some insight into the relative importance of genes and environment for the expression of a given trait.

Nature or Nurture?

For decades, scholars have carried on the “nature/nurture” debate. For any particular feature, those on the “nature” side would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. Those on the “nurture” side would argue that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we are. This debate continues in questions about what makes us masculine or feminine (Lippa, 2002), concerns about vision (Mutti, Kadnik, & Adams, 1996), and many other developmental issues.

Most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behavior as a result solely of nature or nurture, and most scholars believe that even determining the extent to which nature or nurture impacts a human feature is difficult to answer. In fact, almost all human features are polygenic (a result of many genes) and multifactorial (a result of many factors, both genetic and environmental). It is as if one’s genetic make-up sets up a range of possibilities, which may or may not be realized depending upon one’s environmental experiences. For instance, a person might be genetically predisposed to develop diabetes, but the person’s lifestyle may help bring about the disease.

Gene-Environment Interactions

Three views of gene-environment interactions that we will study are:

Range of reaction

Genetic environmental correlation

Epigenetics

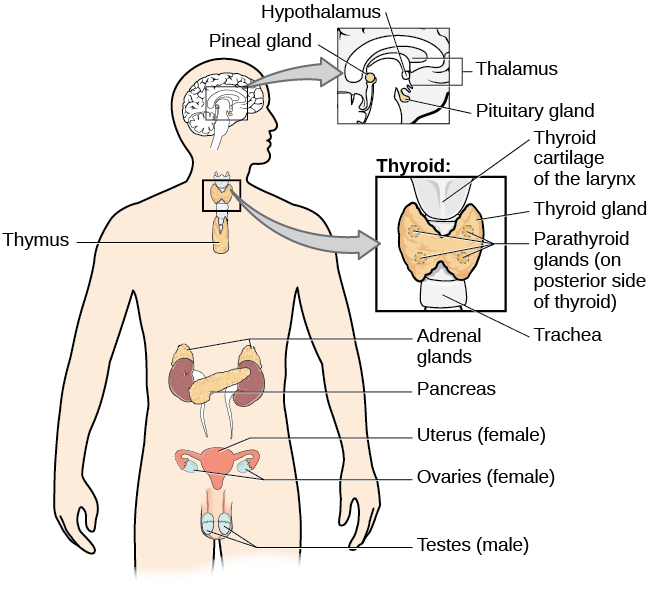

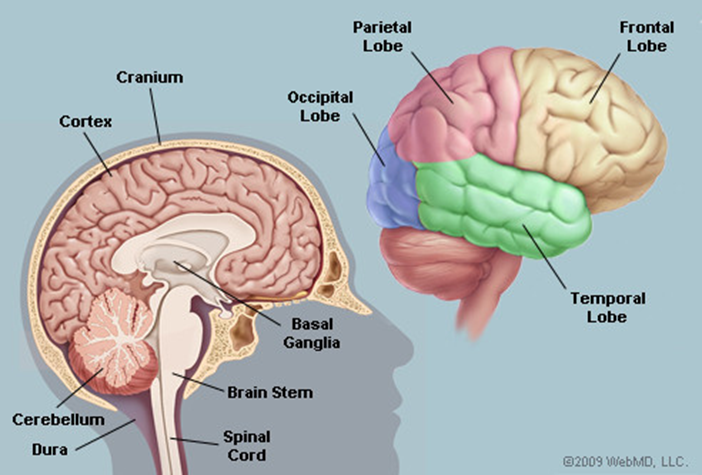

Range of Reaction