13.3 Deconstruction in Montmartre

As we have seen, Academic Art conceived of a painting as a window on the world and a painter’s task as the meticulous imitation of subjects in perspective. That model was challenged by Impressionist atmospheric and subjective media through which subjects were viewed. But while the values of technique had changed, Impressionists still saw their task as capturing a moment of vision within an artistic window frame.

|

| Le Bateaux-Lavoir. (c. 1910). Anonymous Photograph. |

In 1900, laborers and farm workers lived and worked in Montmartre, a semi-rural hill just north of Paris. Among them was a disparate group of artists, many living and painting in le Bateaux-Lavoir, a derelict factory space with cheap rent and space for painting but no running water. The artists who lived and worked there drank in taverns such as the Lapin Agile and shattered the post-Renaissance window altogether. Buckle your seatbelts!

Henri Matisse and Fauvism

At the Autumn Salon of 1905, art critic Louis Vauxcelles was appalled to see a Renaissance sculpture standing among a group of avant-garde paintings: “Donatello au milieu des fauves,” i.e. “Donatello among the wild beasts.” The name stuck and Andre Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Henri Matisse were labelled Fauvists, the beasts. Are you appalled?

|

|

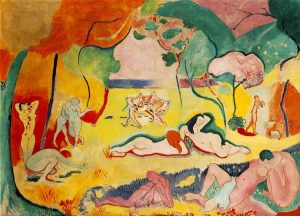

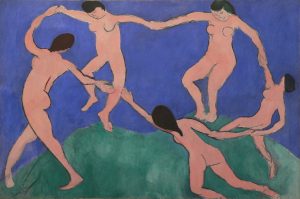

| Le Bonheur de Vivre (The Joy of Life). (1906) Oil on canvas | La Danse (first version). (1909). Oil on canvas |

Taking his cue especially from Cézanne, Matisse radically challenged the Renaissance idea that a painting functioned as a window on the world. Rejecting the rules of linear perspective and precise modeling, he plays a different game. What appear to be its values?

We find them in Formal Elements such as Line. The organic curves of human and vegetal forms of The Joy of Life blossom exuberantly in a celebration of Organic Form. La Danse depicts lively women. But they dance outside of time on a shapeless, dislocated green space. Figures are rendered with a few deft sketch lines and sheer colors dominate. Above all, Color is chosen not to imitate natural hues, but for its expressive energies. In a 1908 article, Matisse detailed his commitment to the value of Expression over Illusionism:

What I am after, above all, is expression. … The entire arrangement of my picture is expressive: the place occupied by the figures, the empty spaces around them, the proportions.

Both harmonies and dissonances of color can produce agreeable effects.

By removing oneself from the literal representation of movement one attains greater beauty and grandeur. … I cannot copy nature in a servile way.

The chief function of color should be to serve expression as well as possible. … To paint an autumn landscape I will not try to remember what colors suit this season.

What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, an art which could be … a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair.

“I cannot copy nature in a servile way.” This is the Modern artist’s great cry of insurrection against a perceived bondage to Illusionism, the Mimetic emulation of “realistic” appearance. Matisse declared independence from any responsibility choose colors that match “the real thing.” He also boldly chose colors that might make us feel squeamish, e.g. the greens in the depiction of the boy with the butterfly net.

|

|

|

| Boy with Butterfly Net. (1907). Oil on canvas. | The Red Studio. (1911). Oil on canvas. | Conversation. (1912) Oil on canvas. |

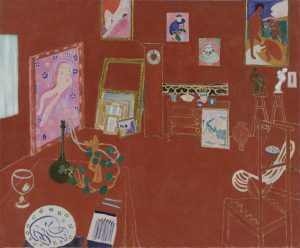

We spent considerable time establishing the significance of Linear Perspective and Virtual Space. Matisse gleefully collapses his interiors into flat planes, figures, objects, and the dimensions of the room pressed into the Picture Pane. Matisse is playing with the techniques and conventions of the Renaissance Model of painting while denying viewers the satisfaction of having their expectations met.

|

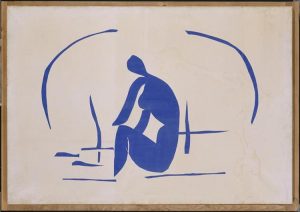

| Baigneuse dans les roseaux (Bather in the Reeds). (1952). Oil on canvas. |

In his later years, weakened by cancer, Matisse drew in the horizons of his ambition. In Bather in the Reeds, the elements of the composition have shrunk to minimalist proportions. A single blue against a neutral background. Ten elegantly simple, organically curved lines. A featureless profile of a figure with limbs that hover between Line and Shape. How much he deftly captures in a few brushstrokes. How elegant the result.

A composition like the Bather in the Reeds probably does not shock us much today. We are well accustomed to simple, Stylized figures in commercial design, advertising, and hotel room art. Matisse was one of the pioneers who broke the bonds of Illusionism.

Picasso’s Deconstructed Images

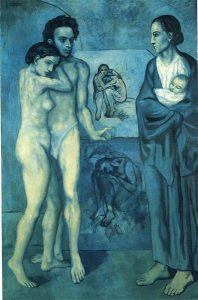

Barcelona native Pablo Picasso first visited Paris in 1900, settling into le Bateaux-Lavoir. Few artists trigger as much adulation and revulsion. Picasso is the master many love to detest. However, looking only at the Blue Period, one might ask what all the fuss was about. The long, lean figures are austere but elegant, quiet celebrations of the lives of the working poor. The cool blues are expressive rather than naturalistic, but not as jarring as Matisse can be.

|

|

|

| Woman Ironing. (1904). Oil on canvas. | La Vie. (i.e. Life) (1904) Oil on canvas. | Old Guitarist. (1904). Oil on panel. |

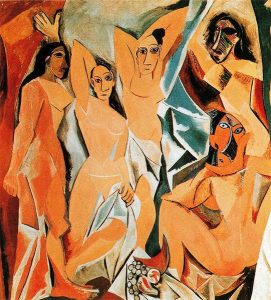

Around 1905, Picasso began a year’s work on a large canvas that he showed to no one until it was finished. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was not received well initially, even by friends and collaborators. It also transformed the world of art.

|

| Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. (1907) Oil on canvas. |

OK, how do we meet the challenge? First, what can we recognize? Human figures—women of a brothel in Montmartre. Fragments of drapery. And fruit, suggesting a conventional Still Life.

But those human figures seem odd. Obviously, they are intensely stylized. Less obvious are the traditions they evoke. The faces of the two central women are stylized in the traditional manner of Spanish folk art. But what of those other faces? We recognize eyes, noses, mouths. But they are rendered in chunks of geometric form, distorted for expressive purposes.

|

|

|

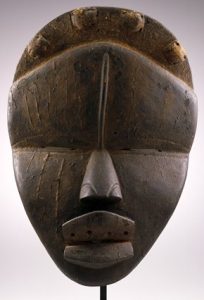

| Dan People. (N.D.) Kagle Mask. Wood, metal | Pende People (20th C.) Mbuyu (Mask). Wood, raffia. | Pende People. (N.D.). Mbangu Mask. |

In the early 20th Century, traditional art of African peoples was becoming popular among artists and sophisticated patrons in European and American cities. A stylish New York apartment might be decorated with Art Deco flourishes and African masks. Picasso embraced the conventions of the African mask, the Geometrical Forms and the freedom to distort them.

| Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Detail. |

Let’s recall that Cézanne broke landscape into formal planes. Picasso similarly deconstructs the human figure into geometrical shapes. He follows African models in two of the faces and more radically deconstructs the women’s bodies into planes of form and color.

The face in the lower right carries these distortions to an extreme, foregrounding pure color and geometric form. The distortions begin to make sense when we realize that we see the case from multiple perspectives at once. The technique remains startlingly provocative even today, yet we should remember that Egyptian painters routinely challenged us to process an image combining profiles of heads, legs and feet with face-on views of torsos and eyes.

Georges Braque & Cubism

Remember Cézanne’s notion that what we see can be broken down into component Geometrical Forms? Georges Braque took up that concept and innovated a deconstructive form of Representation. Cubism analyzed the visual subject, breaking it down into fragmented forms. They then reassembled the fragments into layered, densely interwoven compositions. The muted, narrow color palette focuses the eye on forms and composition that obscure the subject.

|

|

| Georges Braque. (1911). Man with a Guitar. Oil and sawdust on canvas. | Georges Braque. (1911). Woman Reading. Oil on canvas. |

Pablo Picasso collaborated closely with Braque, producing canvases with extremely similar subjects, color palettes, and technique. For a decade or two, Cubism dominated the world of avant-garde art, passing through a number of stages of development. In Picasso’s 1913 composition, we see an example of Synthetic Cubism, fusing paint and canvas with other materials. Collages like this have since become a major tradition in the world of fine art.

|

|

| Pablo Picasso. (1907). Ma Jolie (Femme a la guitare). Oil on canvas. | Pablo Picasso. (1913). Woman with Guitar Charcoal, collage, oil, canvas |

So how do we deal with a Cubist composition? I would suggest that we divide our response. Our What is it? instinct is appropriate here: the titles instruct us on what figures to look for. But if we expect a comfortable experience of Illusionism, we will be deeply disappointed. We can take the composition as a visual puzzle, and there can be pleasure in that. If you take that path, keep in mind that multiple perspectives are simultaneously displayed. One must accept the challenge of seeing from several vantage points at once.

If we look for a satisfying Aesthetic experience, we probably need to let the whole project of Illusionism go. We can see the compositions as intricately interwoven Formal designs: Line, Shape, Monochromatic color, assembled in fascinating, rhythmic patterns. One really can get lost in an exploration of pure design elements.

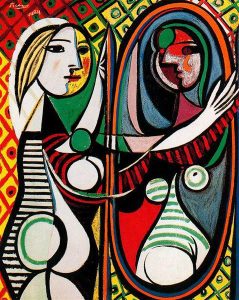

After leaving Cubism behind, Picasso went on to experiment with an astonishing array of Representational techniques and Styles. Some were more uncomfortably experimental than others. Picasso found hundreds of interesting ways to deconstruct the image. Consider this provocative interrogation of multiple perspectives, mirror images, and stylized depiction of forms.

|

| Girl in Front of Mirror. (1932). Oil on canvas. |

If you have the patience, you will find some interesting interplays between elements. Notice that the girl’s faces can be viewed in profile or from face on. Analogous Colors tie the two halves of the figure together. Strong Contour Lines define elegantly elongated body parts. The composition hovers between Representation and pure Aesthetic Form.

Vital Questions

Context

The essence of the Modern mindset is an impatience with tradition and a rushing advance into something new, something that shocks old sensibilities. We have seen that many artistic traditions revere and preserve esteemed Conventions, often suppressing the individuality and creativity of artists. Since the Renaissance, artists had gained prominence and were rewarded for innovation but within the framework of tradition.

The Modern artist felt compelled to do something radically innovative, to deconstruct conventional Content and technique and confront an audience with disorienting uncertainty. From this point forward, a dizzying array of styles and isms would proliferate into our own day. The first decades of the 20th Century flung a door wide open to a lurching, careening future.

Content

At its core, the Modern questions the Content of a work of art. We have explored ways that art has Represented visual subjects, a scene, a human figure, a fragment of a story, a symbolic Signification. The Forms and Media project the subject which dominates an audience’s interest. The Modern artist fractures the projected content and pulls our attention back to the Aesthetic surface of the Medium. In Cubism, extensive obstacles limit our experience of, say, the woman with a guitar, and arrest our eyes in sheer design: Color, Line, Shape. The Modern subordinates Content to Form.

Form

This section’s discussion of paintings has drawn our attention to the Formal Elements of visual art with greater intensity than we needed looking at other traditions. Line. Shape. Form. Color. Texture. Medium. Composition. In a traditional painting, these are means to an end, Illusionism‘s Representation of the subject. In a Matisse, Braque, or Picasso they shoulder their way into the forefront of our awareness. At this point, a tension remains between the advancing forms and the represented subject which is still there, albeit problematically. As we go forward, we will see what happens when pure form erases the represented subject altogether.

References

Braque, G. (1911). Man with a Guitar [Painting]. New York City, NY: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79048?artist_id=744&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

Braque, G. (Autumn 1911). Woman Reading [Painting]. Private collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/georges-braque/woman-reading-1911

Fauvist Movement, The [Article]. (N.D.). Austin Artists Market. https://www.austinartistsmarket.com/fauvist-movement/

Dan People (N.D.). “Kagle” mask. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/113448/kagle-mask-dan

Le Bateau-Lavoir [Photograph] (c. 1910). Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bateau-Lavoir#/media/File:Le_Bateau-Lavoir,_circa_1910.jpg.

Matisse, H. (1952). Baigneuse dans les roseaux (Bather in the Reeds) [Painting]. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/henri-matisse/bather-in-the-reeds-1952

Matisse, H. (1906). Le Bonheur de Vivre (The Joy of Life) [Painting]. Philadelphia, PA: Barnes Foundation. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/henri-matisse/the-joy-of-life-1906

Matisse, H. (1907). Boy with Butterfly Net [Painting]. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1162/boy-with-butterfly-net-henri-matisse

Matisse, H. (1912).Conversation [Painting]. Saint Petersburg, Russia: Hermitage Museum. https://www.hermitagemuseum.org/digital-collection/28401?lng=en

Matisse, H. (1909). La Danse (first version). [Painting]. New York City: The Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79124?artist_id=3832&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

Matisse, H. (1908). Notes of a Painter. Grande Revue. Austin Community College https://www.austincc.edu/noel/writings/matisse%20-%20notes%20of%20a%20painter.pdf

Matisse, H. (Fall 1911). The Red Studio [Painting]. New York: Museum of Modern Art. AN 8.1949. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78389?artist_id=3832&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

Matisse, H. (1947). Two Girls, Red and Green Background [Painting]. Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Museum of Art. AN 1950. https://collection.artbma.org/objects/37506/two-girls-red-and-green-background?ctx=002fd4648624dbb75b87bdea8cfcbcf3b3e547c0&idx=84

Pende People. (N.D.). Mbangu Mask. Terburen, Belgium: Africa Museum. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mbangu_mask_-_Central_Pende,_Southern_Bandundu,_DRC_-_Royal_Museum_for_Central_Africa_-_DSC06657.JPG

Pende People. (20th C.) Mbuyu (Mask). Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/55429/mask-pende

Picasso, P. (1907). Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [Painting] New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79766?artist_id=4609&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

Picasso, P. (1932). Girl in Front of Mirror [Painting]. New York: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78311

Picasso, P. (1937). Guernica [Painting]. Madrid, Spain: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/guernica-1937.

Picasso, P. (1903). Le vieux guitarriste aveugle (The Old, Blind Guitarist) [Painting]. Chicago, IL: The Art Institute of Chicago. Reference number 1926. 253. https://www.artic.edu/artists/36198/pablo-picasso

Picasso, P. (1904). La Vie [Painting]. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1945.24

Picasso, P. (1907). Ma Jolie (Femme a la guitare) [Painting]. New York: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79051

Picasso, P. (1927). Woman in an Armchair [Painting]. Minneapolis MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1517/woman-in-an-armchair-pablo-picasso

Picasso, P. (1913). Woman with a Guitar [Painting]. New York: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79646

Picasso, P. (1904). Woman Ironing [Painting]. New York, NY: Thannhauser Collection, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Accession 78.2514.41. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/3417.

art that follows explicit rules established by a tradition, institution, academy, or school. Sometimes dismissed by the avant-garde art world as overly cautious, derivative, or unoriginal.

a technique of representation that seeks to capture, not the “real thing,” but rather one’s subjective experience of the subject

in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any representation of a visual subject: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement

in visual art, a 2-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth. Line may be straight or curved, directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

in visual art, an irregular form such as a cloud or rocky terrain that suggests natural origin distinct from human artifice

content in art that projects the artist’s inner vision outward, often distorting the subject in “unrealistic” ways

the conviction that a painting or sculpture’s most important task is to imitate the appearance of nature as naturalistically as possible

art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

the virtual window glass through which the 2-dimensional surface of a painting’s Medium—fresco, canvas, panel—"looks out” into a projected space

the conventional values and expectations of painting that derived from the Renaissance tradition: a conception of painting as a window on the world projecting visual space with foreshortening, linear perspective, and accurate mimesis

in visual art, a two-dimensional figure with a more or less defined border displaying only height and width

a representational technique that depicts the idea of a visual subject through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis

a genre of painting, drawing, or photograph arranging inanimate objects such as fruit, flowers, pottery or furniture, usually in an interior scene

in visual art, a form suggesting human artifice in precise, smooth lines, shapes, and forms such as triangles, rectangles, pyramids or cylinders

in visual art, the illusion of 3-dimensional forms and spaces in 2-dimensional compositions by aligning and scaling forms to suggest depth and distance.

a technique which analyzes the visual subject, deconstructing it into fragmented, often geometrical forms that are reassembled into a densely inter-woven composition. A muted, narrow color palette focuses the eye on forms and composition that obscure the subject, depicted from several viewpoints at once

the dimension of an artistic experience that appeals to or challenges an au-dience’s sense of taste and experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A response distinct from “interested” concerns such as ideology, sexuality, social conflict or economics

in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any subject or signification: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement

a restrictive color palette which features only a very few closely related colors

closely related hues on the color wheel that create a harmonious effect

the boundary line that defines a shape or form in a visual composition. A contour line can be directly drawn or achieved merely through contrast be-tween the colors of the subject and the background.

a function of visual art which seeks to emulate a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

a style in the arts associated with the early 20th Century that emphasized formal design and the surface of the medium over any represented or narrated subject

a standard feature of art in a given genre that is expected and understood in the context of origin: e.g. a content, a style, a signification, a theme

the material projected by art for the reader’s mind and imagination. Content can consist of an immediate Subject—e.g. a figure in a painting or a story in a narrative—and Signification, a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative