1.2 Parietal Art

As far as we can tell, all cultures produce art. As they developed domestic technologies such as tools and pottery, cultures from long, long ago applied human instincts of composition and design to their objects. Pottery, for example, has long been decorated with Geometric Form.

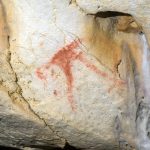

Ancient parietal art corresponds roughly to what people think of today as Fine Art: art that stands separate from practical functions, expressing human design instincts and core ideas. Cultures scattered around the world and often lost in the mists of unrecorded time found themselves incising or painting forms and images on rock formations and the walls of caves.

Ice Age Art

Since the 1870s, stunning, very old images have been found in caves scattered across Europe. Two of the most well-known are in France at Chauvet and Lascaux.

Photographs of art at Chauvet and Lascaux are drawn from these sources unless otherwise noted:

- Chauvet—Open Media Gallery

- Lascaux—Open Media Library

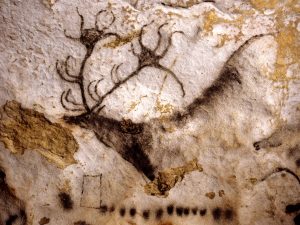

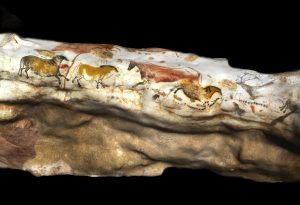

The Lascaux cave was discovered in 1940 and explored initially by the Abbé Henri Breuil, a pioneer scholar of parietal art. Its images are currently dated to circa 18,900 BCE. The French Ministry of Culture has made a glorious virtual tour. Please watch. You’ll be glad you did!

|

|

|

| Lascaux: Black Stag | Lascaux: Brush Painted Horse | Lascaux: Panel of the Beasts |

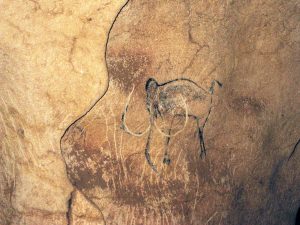

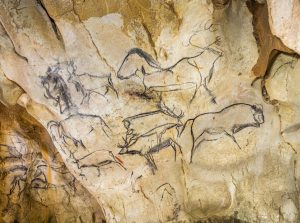

Discovered in 1994, the magnificent art in the cave at Chauvet is currently dated to about 34,000 BCE (The Chauvet-Pont d’Arc Cave, 2015). You can track at your own pace through the cave virtually in a virtual tour.

|

|

|

| Chauvet: Panel of Horses | Chauvet: 3 Small Mammoths | Chauvet: Reindeer Panel |

What do we see?

Encountering unfamiliar art, we begin by simply observing. The Lascaux and Chauvet web sites linked above offer scores of photographic images to explore. The images are dominated by animals, especially birds, predators, game animals—bison, deer, mammoths—and horses. These images are representational:

In contrast to the emphases of later art, images of people are extremely rare. However, we do find scores of handprints, channels to the ghostly afterlife of distant ancestors. These prints are either positive—pigment on the hand is pressed against the wall—or negative—the pigment is blown around the hand.

|

|

|

| Chauvet: Negative Hand | Chauvet: Positive Hand | Chauvet: Hands, Dotted Half Circle |

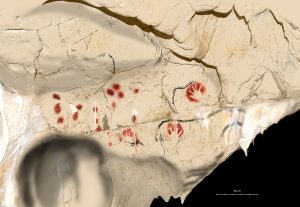

Many of the parietal animal figures are composed with astonishing skill and elegance. Some appeal to our contemporary sensibilities and may seem beautiful. However, von Petzinger cautions that an emphasis on figurative images is misleading: actually, simple, sign-like geometrical forms outnumber the representations of animals by as much as two to one (161). The most common forms include patterns of red dots and incised, usually parallel lines. Note the dotted contour line of the animals in the top right image below.

|

|

|

| Lascaux. Panel of Six Dots | Chauvet: Panel of Red Dots | Chauvet: Dots and Dotted Animal Contours |

|

|

|

| Chauvet: Panel of Red Signs | Lascaux: Incised Cross-Hatch Lines | Chauvet: Ibex or abstract? |

Art that presents design without attempting to actually portray anything is called abstract.

We may be challenged by abstract art: after all, we generally want to ask, but what is it? Yet a great deal of the art produced in human history is abstract. Pottery was decorated with lines and zigzags and geometrical designs thousands of years ago and so is our kitchenware today. Furthermore, the boundary between the abstract and the representational is often blurry. Are these designs on the cave walls abstracts or representations of birds or ibexes (deer-like game animals)?

|

|

|

| Chauvet: Aviform (Bird-like) | Lascaux: “XIII” Lines | Chauvet: Triangular Signs |

Or are they signs? Have images become abstracted to form graphic symbols, an early form of writing? What is the significance of the “XIII” sign? The “Red Signs”? von Petzinger’s book title—The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World’s Oldest Symbols—suggests her view. These designs might represent the birth of a shared symbol system, although our knowledge of the culture is too fragmentary to allow us to crack the code.

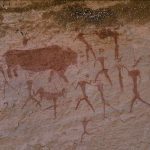

Our observations have drawn us to the verge of contextual questions. We see predatory and game animals and we wonder about their significance. We imagine a hunter-gatherer culture and speculate that these images might be magical charms to facilitate the hunt or ward off danger. Are they totems designating social clans? And what of those abstract, perhaps symbolic signs? Are we seeing the emergence of writing?

Here, remember our caution: as we approach radically unfamiliar art, we need to hold our first impressions loosely. Our responses flow from our own perspectives. We need more information. We need expertise.

Contextual Background: Dating, Media, Technique

Archaeologists situate this art in the Paleolithic era, i.e. the early Stone Age. Dating techniques have evolved as scholars from a variety of disciplines have collaborated. The carbon in organic pigments such as ochre and charcoal decays at a known rate. Geographical analysis dates the rock and, in some caves, limestone layers that form over these pigments can be dated by Uranium-series analysis (von Petzinger 2016, p. 131). Archeologists and anthropologists draw ever more comprehensive maps of human culture: technology, tools, dwelling patterns, and meaning systems. Genetic sequencing has stabilized our ideas of migration patterns and time frames. Through “stylistic dating,” art can date itself (von Petzinger, 2016, p. 132). Comparative analysis of art in various regions and sections of the caves indicates sequences of influence in style and subject matter. Current estimates date the oldest parietal art to 30 to 40,000 years.

So what technology was available to artists that long ago? Scholars have much to tell us about how these images and signs were produced using available media.

The base media for the designs at Chauvet and Lascaux were, of course, the stone walls and ceilings of the caves. Most simply, they were incised in soft rock with tools of stone, bone or antler. von Petzinger (2016, p. 123) acknowledges that it can be difficult to distinguish incised lines from seams in the rock.

Colors were drawn from charcoal or with ochre, a clay compound that gathers yellowish or reddish hues from iron ore. These pigments were applied with hands, fingers, or brushes. In spit-painting, the artist blows powdered pigment from a hand or spits watered color onto the surface (von Petzinger, 2016, p. 121-122).

|

|

|

| Chauvet: Incised (Engraved) horse | Lascaux: Spray Painted Horse | Chauvet: Finger fluted owl |

Finger Fluting, a less common technique, composed forms and figures by drawing fingertips through soft stone or thin layers of clay on cave walls. von Petzinger (2016, p. 127) observes that finger fluting designs were often composed by children between two and fifteen years.

The Venue Question

If you are like me, you’d love to visit Chauvet or Lascaux. But if you do so, you would not actually be visiting the caves. To protect the fragile art and rock faces from hordes of touring visitors, the French Ministry of Culture has supported the development of two painstakingly reproduced facsimiles open to the public:

Grotte Chauvet 2,[1] a precisely modelled, full scale facsimile of the entire cave.

Lascaux IV visitor’s center with facsimiles of two rooms art: the Hall of Bulls and the Axial Recess

These visitor centers function as museums, complete with gift shops and cafeterias. The displays are comfortably arranged, artfully lit, and annotated to accommodate contemporary standards for curated display. Experienced thus, they support our expectations of the museum function of art. And, surely, parietal art must have been made and viewed with similar expectations. People lived in the caves, right? Those horses and lions decorated their lives like prints hanging on our living room walls?

Well, no. von Petzinger explains that people in these cultures tended to live near but not in caves (2016, p. 211). Certainly no one lived in the caves at Chauvet or Lascaux. They remained undiscovered for thousands of years, deeply submerged, accessible only through harrowing, constricted openings that pose ordeals for contemporary visitors equipped with electric lighting, helmets, lifelines, and radio links. These caves were no one’s home and no one strolled comfortably in.

To approach the ancient experience of these caves, we must surrender our ideas of museum art. People journeyed deep through lightless, constricting, forbidding stone passageways lit only by flickering torchlight. Artists worked in darkness and their audience peered through shifting, deeply shadowed torchlight to watch evanescent forms emerge and recede. Lewis-Williams evokes other sense experiences: temperature, dampness, smells, and echoing sounds. Descending into these caverns would have been an immersive and overwhelming sensory experience (p. 220). We can sample the mesmerizing experience of the caves at Chauvet by firelight in The Dawn of Art, a moving virtual tour filmed by Atlas V (February 2020).[2]

So what was this art all about? Why did artists risk their lives to descend into the darkness, inscribing forms rarely viewed by an audience?

[1] Grotte Chauvet 2: i.e. Chauvet Cave 2.

[2] Dawn of Art: On the Meet our Ancestors web page, click into either of the Take the Tour videos in English or French.

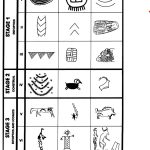

A Map of Ancient Cultural Signs

As famous as they are, Chauvet and Lascaux are far from unique. As of 2016, von Petzinger (p. 163) has counted and explored 368 sites from the Balkans to Spain. As a graduate student, she recognized design patterns shared by cultures separated by thousands of years and scattered in caves across Europe. Focusing not on the lions, horses, and deer but on geometrical, abstract designs, she catalogued similar forms, finding that thousands of signs in 70 sites boiled down to 32 common types.

|

| von Petzinger. (2016) Table: 32 abstract signs common across Europe |

von Petzinger feels that the persistence and commonality of these signs powerfully suggests a system of Signification that was not quite writing but certainly must have been meaningful in multiple cultures that dutifully maintained these traditions. However, because the gap between our culture and those distant ones is so great, she doubts we will ever be able to crack the code.

The San: a living Tradition

Cracking the code of European parietal art faces an insurmountable barrier: the culture died long ago. We really know very little about it. The situation is very different with rock art composed by the San people of southern Africa. The nomadic San of the Kalahari Desert live in direct cultural descent from the oldest human ancestors on earth. Though of course pressured by the modern world,[1] the San maintain the rituals and myths of the extremely distant past. They contribute to parietal art displays carved into rock outcroppings begun many thousands of years ago.

San images below are drawn from …

- Bradshaw Foundation: The Rock Art of Africa gallery

- San Rock Art gallery (with permission): ARADA African Rock Art Digital Archive

- Zamani Project: Game Pass Shelter for text, photos, and 3-D models

[1] San culture: some San languages have died out. However in the late 19th century anthropologist W. H. E. Bleek was able to compile a lexicon of the /Xam language by interviewing Diä!kwain, one of the last surviving speakers (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p. 136).

Lewis-Williams (2002, Chapter 2) reviews stages of perception through which Westerners have viewed the San and their art. For centuries, they were dismissed as primitive, simple, unworthy of study. Then, working in obscurity, a 19th Century linguist named Wilhelm Bleek and his sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd rescued some San people from jail and volunteered to be instructed in their language and culture. In the 1950s, John and Elizabeth Marshall, drew on Bleek and Lloyd to begin viewing San art from the San perspective.

Ethnographies open fresh readings of parietal art. The San are spiritually led by shamans, people who enter trance states that are thought to cross the boundary into the spirit world:

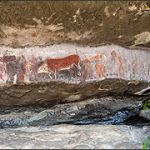

Drawing on testimonies from members of a living culture, Lewis-Williams now read San rock art as expressions of mediated encounters with heavenly spirit worlds. This reading transformed the conventional view of a panel of images under a rock shelter in the Khahlamba-Drakensberg mountains of South Africa. They enhance our perception of the images with a drawing by Stephen T. Basset.

|

|

| Ceiling panel, CHI1 Rock Shelter ceiling. (c 1,000 BCE) uKhahlamba-Drakensberg mountains | Stephen T. Basset. (2009). Drawing enhancing the ancient images. |

Please be sure to click the thumbnails to see the full images. One of the elands raises its head along the line of a seam in the rock. In San religion, the eland is a “connecting element” between “spiritual realms above and the level on which people live” (Witelson, et al. 2021). Through the seam in the rock, the eland’s raised head seems to smell the spirit realm and its mystical rain.

|

|

|

| Linton Panel (N.D.): National Museum, Capetown, S A | Thomas Dowson (1987): Line drawing of the Linton Panel | Shaman Healing Dance (N.D.): (Bradshaw Foundation) |

One of the most comprehensive depictions of curing dances in San art is the so-called Linton Panel, now on display in Cape Town’s National Museum. The images depict a shamanistic ritual with dancers, spirit animals, and one shaman being held underwater in the underworld.

Entoptic Images

|

|

|

|

| David Lewis-Williams (1988, p. 206). | San Dotted Lines (ARADA) | San Grid–Crosshatching (ARADA) | San “Navicular” sign (ARADA) |

OK, so we can see the elands as spirit animals. But what of the abstract designs, similar to von Petzinger’s findings? Lewis-Williams uses the phrase entoptic[1] phenomena for visual images that arise, not from seeing external objects, but from “anywhere within the eye itself and the cortex of the brain” (2002, p. 126). You can easily experience these universal images: simply press your fingers against your closed eyelids.

One can also, according to witnesses, access them in visionary trances. Entoptic forms in the parietal art, Lewis-Williams believes, reflect the shaman’s journey into altered consciousness. Entoptic images are construed, he believes, by hunter-gatherer shamans as the sacred eland whose blood brings rain to arid lands. The arrows represent not only prayers for rain, but also wounds from which the San people sought healing.

Notably, the rain animal is often depicted as bleeding through its nostrils. Shamans often bleed through the nostrils in moments of intense vision, a moment of transition often referred to as “dying,” a hallucinatory merging of shaman with spirit sacred animal that is recorded in art.

|

|

|

| Bamboo Hollow: Capturing the Rain Animal (ARADA) | Game Pass Shelter: Shaman holding tail of dying eland (Zamani) | Game Pass Shelter Diagram (Bradshaw) |

Images composed on the face of the Game Pass Rock Shelter[2] in South Africa’s Drakensberg mountains are seen as a Rosetta Stone[3] of San art. Holding the tail of eland, the human figure can be read as a shaman in the process of metamorphosis, becoming the spirit eland.

[1] Entoptic: in Greek, entoptic would signify within vision, that is an image arising not as a response to the reflection of light by external objects, but internally, from within the individual’s visual system integrating eyes, optic nerves, and brain.

[2] Game Pass Rock Shelter: the images in the rock shelter are not firmly dated, but are thought by some to be 3,500-4,000 years old.

[3] Rosetta Stone: in 1799, a French soldier serving in Egypt discovered a stone with parallel inscriptions in Greek, demotic (everyday, common) Egyptian, and hieroglyphics. Since the first two scripts were known, scholars were able translate the hieroglyphs bearing the same message. This cracked the code for Western scholars in deciphering hieroglyphic texts in general, a task previously held to be impossible. Thus, the phrase Rosetta Stone has come to signify a key to understanding previously elusive materials.

Back to Ice Age Europe

But Lewis-Williams does not stop there. He finds entoptic imagery in the psychological literature on altered states of consciousness: trances, hallucinations, and dreams. He finds it in traditional art forms around the world, in Chumash art of the American Southwest and that of the Coso people of Southern California. If entoptic images are shared across human consciousness, one could expect to see it everywhere.

And, yes, Lewis-Williams finds it in the caves of Ice Age Europe. If his reading is correct, the art deep in an Ice Age cave makes no attempt to portray the “realistic” appearance of actual bison or horses. It would not have been expected to do so. Rather, these ancient artists may have been tracing the phantasms of altered consciousness in trance states. Lewis-Williams invites us to imagine “the rock wall as a membrane between people and the subterranean spirit world” (2002, p. 217). Animal imagery draws the shaman’s visions into the frontier separating the mundane from the spiritual world.

|

|

|

| Chauvet: Negative hand (Chauvet Media Library) | Chauvet: Panel of Positive hands (Chauvet Media Library) | Chauvet: Palm Prints as a Cloud of Dots (Chauvet Media Library) |

Conceiving the rock face of the cave, not as an irregular canvas but as a membrane of the spirit transforms our understanding of those abundant hand images. Lewis-Williams suggests that “the act of making the prints [was] as important as … the resulting shape of a hand” (p. 217). In the case of negative prints, the “hand ‘disappeared’ behind a layer of paint, ‘sealed into’ the wall,” that is into the spirit realm. The image “‘dissolved’ the rock and facilitated intimate contact with the realm behind it” (p. 218). This art is not about emulating the form of the human hand but rather about caressing infinity.

Other Readings

Over several decades, this shamanistic reading has gained increasing influence. However, not everyone agrees. Dederen (2021) questions the Lewis-Williams reading. She feels that San imagery can just as easily be seen as a hunt-oriented people bonding spiritually, as do many hunting cultures, with their game. von Petzinger acknowledges similarities between the signs of San and Ice Age art but draws on her quantitative charting to assess the strength of the hypothesis: “It doesn’t seem like we’ve found a lot of evidence to support the existence of shamanistic practices during Ice Age Europe” (2016, p. 260). She sees in the parietal art an expression of spiritual beliefs, but wonders if it was shamanism, animism, or ancestor worship.

Vital Questions: Our Readings

So. Where do we stand? Let’s consider our vital questions.

Context

Encountering art about as distantly removed from a modern context as is conceivable, we were challenged in our museum function assumptions. This art is not hung on a wall for casual reflection. It has little interest in portraying recognizable visual subjects as realistically as possible within an observed visual scene. The expectation for that sort of art, as we will see, derives from Renaissance models.

Whatever our reaction to the Lewis-Williams reading of parietal art as entoptic images from altered mental states, it seems clear that these artists were participating in ritualized, spiritual encounters of some kind. But what do we mean by spiritual? We will use the term spiritual to refer to one of art’s most universal concerns:

Surely these parietal artists were interested in something like that. People don’t risk their lives crawling through tunnels in the dark to idly reflect on figures and designs. The very acts of delving deep or scaling elevations strongly suggest rituals that probe the transcendent realms above and below us. I am personally arrested by that concept of a hand caressing the surface of rock felt as the membrane of infinity.

Of course, our spiritual orientation may be very different from that of the San or the people of Chauvet and Lascaux. We may even feel put off by features that seem to clash with our values. Still, I think there is a shared humanity to be seen and experienced in this as in all art. I am personally arrested by that concept of a hand caressing the surface of rock felt as the membrane of infinity.

Content

Our contextual information aids us in characterizing the contents of these ghostly images. Animal figures. Handprints. Simple geometric forms. In the case of the San, we can confidently interpret the signification of those spirit elands. The images at Chauvet and Lascaux will probably remain enigmatic.

For now, let’s notice our hunger for signification. Art presents content, and, one way or another, that content pushes us toward meaning. At one level, we simply ask, what is it? Fairly rudimentary parietal designs can be seen as bison or horses or deer, but … are they? Do the designs below signify mammoths? Ibexes? Birds?

|

|

|

| Chauvet: Mammoth with Long Trunk | Chauvet Ibex Sign | Chauvet: Aviform Sign |

After we recognize them, visual subjects can signify stories, ideas, or associations. Obviously, these issues tie back into context. As we shall see, a visual subject can open a deep and wide array of thematic significations.

Form

We will not fully encounter art until we engage the form through which it presents its contents. Form begins with media, technology, and technique. Parietal artists of the distant past used primarily two pigments to achieve color: charcoal and ochre. They incised lines and forms in the rock and used hands, brushes, and breath to apply pigment. We must not forget the contribution made to the effect by their stone surfaces. Each image is applied to a chosen spot within a seamed, pitted, and irregular panel of stone, all of which detail adds to the composition. The textures and temperatures of the walls and ceiling enrich the images and call to all our senses.

So there is much to learn about experiencing art from very old parietal compositions. And, of course, ancient art was not restricted to the San and the European Ice Age. Let’s explore some ancient traditions closer to our contemporary context.

References

African Rock Art Digital Archive (ARADA) [Website]. (2021). Rock Art Research Institute. http://www.sarada.co.za/#/library/San%20rock%20art/images/

Atlas V. (February 2020). The Dawn of Art: a Virtual Journey Inside Chauvet Cave [Video]. Google Arts & Culture. Meet our Ancestors. https://g.co/arts/GBK1AHqSNoqNRjFTA

Basset, S. T. (2009). Ceiling panel, CHI1 Rock Shelter ceiling [Documentary copy]. uKhahlamba-Drakensberg mountains: South Africa. In Witelson, D. M., Lewis-Williams, D. Pearce, D, and Challis, S. (2021). Reimagining Rock Art in Southern Africa. https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/rock-art-south-africa/

Bradshaw Foundation. (N.D.). The Rock Art of Africa [Website Gallery]. https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/africa/index.php

The Dawn of Art [Video] (2020). Meet our Ancestors [Web page]. Google Arts & Culture https://g.co/arts/GBK1AHqSNoqNRjFTA

Dederen, J-M. (2021). Trivial pursuit? Interpreting San rock art in terms of the mystical bond between hunter and prey. Pharos Journal of Theology. 102 (Special Edition 1) 1-17. https://doi.org/10.46222/pharosjot.102.18

Dowson, T. (1987). The Linton Panel [Line drawing]. Archaeology Travel, https://archaeology-travel.com/friday-find/linton-panel/

Game Pass shelter image [Diagram]. (ND) Bradshaw Foundation. https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/south_africa/san_rock_art/index.php

Game Pass shelter image [Photograph]. (ND) Bradshaw Foundation. https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/south_africa/san_rock_art/index.php

Google Arts & Culture. (2020). Meet our Ancestors. [Web page] https://artsandculture.google.com/project/chauvet-cave

The Chauvet-Pont d’Arc Cave [Web site]. (2015). French Ministry of Culture and Communication. https://archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet/en

Chauvet Media Gallery [Photographic Gallery]. (2015). The Chauvet-Pont d’Arc Cave. French Ministry of Culture and Communication https://archeologie.culture.gouv.fr/chauvet/en/mediatheque?combine=

Grotte Chauvet 2 [Web page]. (N.D.). Ardeche, FR: Ardèche Department and the Rhône Alpes Region https://en.grottechauvet2ardeche.com/discover-the-cave-chauvet-2/

Lascaux IV [Web page]. (N.D.). Lascaux: International Center of Parietal Art. https://www.lascaux.fr/en

Lascaux: Open Media Library [Web Page]. (N.D.). France: Ministry of Culture https://archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en/mediatheque

Lewis-Williams, D. (2002). The Mind in the Cave. London: Thames & Hudson.

Lewis-Williams, D. and Dowson, T. A. (1988). The Signs of All Times: Entoptic Art in Upper Paleolithic Art. Current Anthropology, 29(2), 201-245.

Linton Panel [Parietal Art]. (N.D.) Capetown, SA: National Museum https://www.iziko.org.za/collections/archaeology

San people. (c 1,000 BCE). Elands [Photograph]. Witelson, D. M., Lewis-Williams, D. Pearce, D, and Challis, S. (March 31, 2021) Reimagining Rock Art in Southern Africa. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/an-ancient-san-rock-art-mural-in-south-africa-reveals-new-meaning-157177

Shaman Healing Dance in San Rock Art [Photograph]. (N.D.). The Rock Art of South Africa. [Web page]. Bradshaw Foundation https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/south_africa/san_rock_art/index.php

von Petzinger, G. (2016). The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World’s Oldest Symbols. New York: Atria.

von Petzinger, G. (Nov.2015). Why are these 32 symbols found in ancient caves all over Europe? [Video]. Ted Talks https://www.ted.com/talks/genevieve_von_petzinger_why_are_these_32_symbols_found_in_ancient_caves_all_over_europe

Witelson, D. M., Lewis-Williams, D. Pearce, D, and Challis, S. (May 11, 2021) Reimagining Rock Art in Southern Africa. Sapiens Anthropology Magazine. https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/rock-art-south-africa/

Zamani Project. (2020). Game Pass Shelter: The “Rosetta Stone” of South Africa. https://www.zamaniproject.org/site-south-africa-drankensberg-gamepass.html#next

in visual art, a form suggesting human artifice in precise, smooth lines, shapes, and forms such as triangles, rectangles, pyramids or cylinders

art that is designed to create complex aesthetic experiences rather than to achieve a practical or didactic purpose. Often opposed to Decorative Art or Commercial Design. A conceptual distinction that arose in the 18th Century and remains influential, though subject to increasing criticism

a visual or textual representation that is understood within a context to stand for some other thing or meaning

a technique of composing forms and figures by drawing fingertips through soft stone or thin layers of clay on cave walls

the assumption that paintings and sculptures are intended to be displayed for public reflective viewing by people who seek beauty, ideas, and interesting experiments in vision

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

visual images that arise, not from seeing external objects, but from “anywhere within the eye itself and the cortex of the brain” (Lewis-Williams, 2002, p. 126).

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values