Chapter 11 a Glittering New World

Emily Dickinson. (1891). Poem #383

I like to see it lap the Miles –

And lick the Valleys up –

And stop to feed itself at Tanks –

And then – prodigious step

Around a Pile of Mountains –

And supercilious[1] peer

In Shanties – by the sides of Roads –

And then a Quarry pare

To fit its sides

And crawl between

Complaining all the while

In horrid – hooting stanza –

Then chase itself down Hill –

And neigh like Boanerges – [2]

Then – prompter than a Star

Stop – docile and omnipotent[3]

At its own stable door –

I like to see IT … Wait. What is this IT that laps miles, feeds itself at tanks, steps around mountains, chases itself hooting down hills? Boanerges—Sons of Thunder—a hint?

By the 1850s and 1860s, when Dickinson was writing her best verses, European and American societies, economies, and landscapes had been profoundly transformed by an invention that was sometimes thought to have conquered time itself: the railroad.

|

|

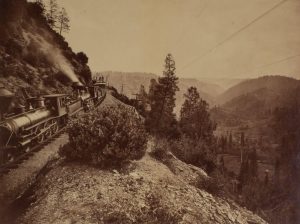

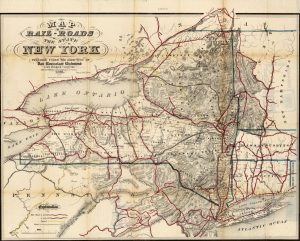

| Carelton Watkins. (c 1876). Rounding Cape Horn, Central Pacific Railroad. | Van Rensselaer Richmond. (1861). Map of New York State railroads. |

|

|

| Claude Monet, C. (1877). The Gare St-Lazare. Oil on canvas. | William Powell Frith. (1862). The Railway Station [Painting]. |

Traditional societies in Europe had for centuries been shaped by a Medieval social structure. Power and wealth were heavily concentrated in a very small, land-owning aristocracy descended from Medieval warriors: the French referred to this as l’ancien régime. Apart from the church, the rest of society was considered to be commoners or peasants, a small percentage of whom throve as traders or in crafts. The vast majority of the society lived poverty-stricken lives, sometimes as unfree serfs whose labor was owned by aristocrats.

By the late 18th Century, science and technology were subverting this traditional society on several levels. Concepts of the world were transformed by natural philosophy (science) which provided rational, measurable ways to understand reality through observation and experiment. These experiments led to new technologies, especially the steam engine which powered mechanical looms and locomotives strong enough to pull strings of cars on rails.

The resulting industrial revolution produced massive income streams from brand new industries, undermined the authority of the traditional aristocracy, and severely challenged the economic survival of the working classes. The new world was thrilling, terrifying, and utterly disconcerting.

As they always do, artists responded. In this chapter, we explore some of the ways that writers and artists reinvented their conventions and techniques to address the world they faced.

Sources

Dickinson, E. (1891). Poem #383. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56019/i-like-to-see-it-lap-the-miles-383

Frith, William Powell. (1862). The Railway Station [Painting]. London, UK: Royal Holloway College, University of London. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Railway_Station

Monet, C. (1877). The Gare St-Lazare [Painting]. London, UK: The National Gallery. AN NG6479 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/claude-monet-the-gare-st-lazare

Richmond, Van Rensselaer. (1861). Map of the railroads of the State of New York. Washington DC: Library of Congress. ON 2015591070. https://www.loc.gov/item/2015591070/

Watkins, Carelton Emmons. (c 1876). Rounding Cape Horn, Central Pacific Railroad, Placer County, California [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:44._Cape_Horn,_C.P.R.R.jpg