1.3 Art of the Nile

Ancient art. What comes to your mind? Egypt, right? Pyramids, mummies, and tombs. Pharaoh, King Tut, and Nefertiti. The Mummy, Indiana Jones, and Tomb Raider. When traveling displays of Egyptian artifacts arrive at a museum, lines circle the block.

Let’s try to move beyond the mummy’s curse hype and ask ourselves what we should understand about Egyptian art and what it can teach us about art in general. Our Vital Questions can help.

Dynastic Context

The context of ancient Egypt was defined by the River Nile which conferred a sliver of green abundance on an arid desert landscape. Each year, the river would flood, creating a fertile zone along the banks. This annual gift of life provided the basis for agricultural plenty that supported internal wealth and dominance of international trade. Egypt became one of the great world powers of the day.

Monuments & Steles: Art of Intimidation

Egyptian dominance derived from trade, wealth, and the armies that the Nile’s abundance paid for. It was also supported by a rich artistic tradition. The Narmer Palette proclaimed the achievement and authority of the kings which unified the kingdoms of the Upper and Lower Nile in about 3100 BCE.

|

| Narmer Palette, both sides. (c 3150 BCE). Slate relief. |

Like most ancient steles— a slab that marks a boundary or commemorates the authority, victories, and achievement of a regime—the Narmer Palette performs a Didactic role as a work of art. It teaches a lesson, or rather, three lessons. It proclaims the political power of the king, the cultural dominance of the Naqada people, and the religious lesson of submission to the will of the gods. The faces of the palette are divided into “registers,” or zones. At the top, we see the invocation of a deity, the cow goddess Hathor. In the middle register (obverse face), we see King Narmer smiting an enemy under the gaze of the falcon god Horus.

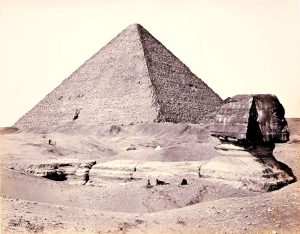

Today, the Naqada society is seen as the precursor to 31 dynasties of royal dominion that endured for over 3,000 years. Generations of Pharaohs used Didactic art to intimidate enemies, allies, trading partners, and citizens. The most famous of these art projects were massive monuments the scale of which were designed to strike dumb members of cultures which lacked Egypt’s economic and technological resources.

|

|

|

| Francis Frith. (1860). The Great Pyramid and Sphinx |

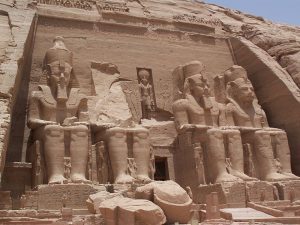

Abu Simbel. (c 1270 BCE). Four Colossi of Ramses II. |

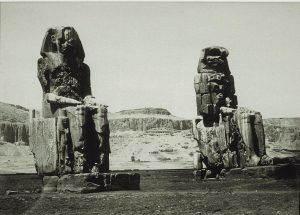

Francis Frith. (1860). Colossi of Memnon. |

From ancient kings to corporations in our age, the powerful erect massive, monumental buildings and art works to intimidate and assert power. Ancient Egyptian architecture and statuary—the pyramids, the Sphinx, the temple compound at Luxor—were erected to project power and affirm the blessing of the gods in opposition to every rival … now and in the future. Colossal statues of pharaohs like Ramses II sought to intimidate generations yet unborn.

Of course, no one beats time. Pharaohs died. The empire was repeatedly defeated, eventually by Greeks and Romans. Monuments crumbled and collapsed. In 1818, English poet Percy Byssche Shelley was intrigued by press drawings of archeological discoveries. Eroding monuments such as the Colossi of Memnon (above), invoked the irony of human aspiration.[1] Shelley wrote a sonnet reflecting with melancholy irony on human mortality.

|

| Curran (1819). Portrait of Shelley. Oil on canvas |

Percy Bysshe Shelley. January 11, 1818. Ozymandias.

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

[1] As quoted in Mikics, Shelly’s poem channels the irony of an ancient Roman historian named Diodorus who quoted an inscription on an Egyptian monument: “King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work.”

Potent Images

Egyptian artisans produced some of the most spectacular art ever made, yet their culture had no word for art and no concept of art for art’s sake. For the Egyptians the activity that we today consider art served a greater purpose: to embody life (Silverman, 1997, p. 212).

“No concept of art for art’s sake”: Silverman leads us across the contextual gap that divides from the ancient Nile. What do “we” expect from art? Even if we know little about the Art for Art’s Sake movement in 19th Century France, we are likely to expect art to explore our perception of visual images and cultivate beautiful formal effects. This is not, Silverman warns, what Egyptian art was intended to do.

|

|

|

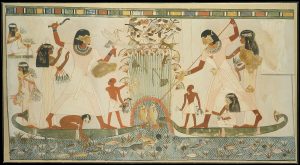

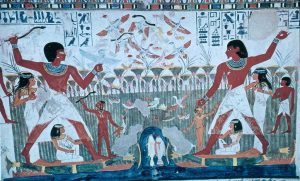

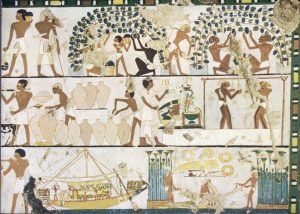

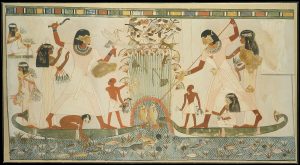

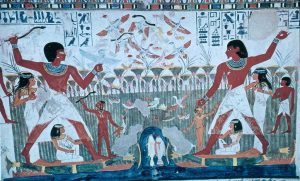

| Hunting Scene. (c 1415 B.C.). Tomb of Menna |

Fowling Scene. (c 1400 BCE). | Grape Harvest. (13th C BCE). |

Clearly, these everyday scenes “embody life.” As a householder today hangs a panorama on the wall, so must these paintings have graced ancient homes. But wait. These images were composed on the walls of tombs. Indeed, the vast majority of ancient Egyptian art, from pyramids to mummies, was focused on death. Images and artifacts symbolically represent life and then are believed to spiritually project them into infinity.

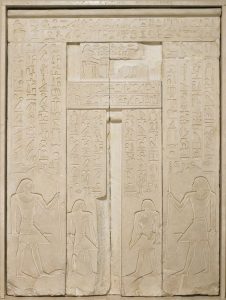

|

|

|

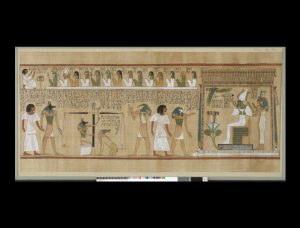

| False Door—Tomb Wall (c 2400 BCE). Relief. |

Hunefer Book of the Dead (c 1317-1285 BCE). Papyrus scroll |

Funerary Model Boat. (c 2100-1780 BCE). Wood and pigment. |

The false door in the tomb wall above provides a portal for the deceased soul to begin the journey into the afterlife. The Book of the Dead instructs the soul in navigating the ordeal of judgment. Models of servants, boats, and other luxuries equip the soul to enjoy an affluent way of life in the hereafter.

Content and Signification

Our second vital question asks about content: what is the work delivering to us? At this point, we should make an important distinction:

In the visual arts, the term Representation refers to a work’s designation of a Visual Subject. Those tomb wall compositions depict for us human figures engaged in hunting or harvests. What is it? No problem.

But what do these images mean? Students sometimes get nervous about levels of meaning beyond the what is it question. And yet, human beings always ask about what things mean. Suppose someone frowns when you speak. You want to know what that frown means, right?

So we see a figure of a well-dressed man hunting while surrounded by other people. It’s not hard to interpret this as a picture of affluence that affirms the stability and prosperity of Egyptian society. The social implications are signified without being directly represented.

Today, the word Icon is used by some scholars to indicate a symbolic form which signifies a meaning which it resembles in no way (in the glossary entry, meaning #4). Thus, the octagonal shape of a stop sign tells us to stop, but only by convention–the shape in no way depicts the act of stopping.

Signifying Scale

Let’s look again at the Narmer Palette and Hunting Scene. What do you notice?

|

|

|

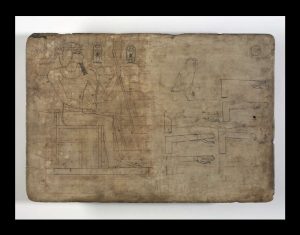

| Narmer Palette, both sides. (c 3150 BCE). Slate relief. |

Hunting Scene. (c 1415 B.C.). Tomb of Menna |

Canon of Proportion. (c 1550-1292 BCE). Drawing board. |

These compositions present human figures with signifying distinctions in scale. On the palette, the king is larger than the figures of conquered warriors and slaves. Similarly, the hunter is larger than wife, servants, and slaves, each allocated to a social caste by their decreasing size.

In many ancient societies, figures are by Convention scaled according to social status. Notice how the drawing board shown above provides draftsmen with guidelines for scaling figures according to a canon[1] designating appropriate ratios of height.

[1] Canon: in this cases, the word refers to a standard by which an image is measured and assessed.

Convention and Attribute

Sometimes, represented subjects pose visual puzzles. Many of the human figures depicted in Egyptian art are strange, hybrid forms topped with heads from animals. What do these signify? This is where Context comes back into play. Every culture teems with signs and symbols which are processed instantly and without thinking by its members. For millions of people in Euro-American societies, a Christian cross immediately signifies a great deal more than what it visually depicts.

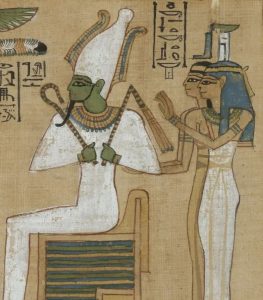

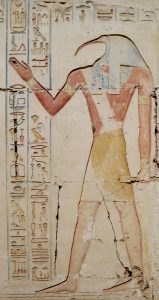

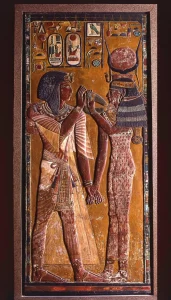

While we may today be puzzled by those Egyptian hybrid figures, they would have been clear in their day. The hybrid figures depict the deities of the Egyptian canon. A conventional code identifies each deity with a standard attribute, i.e. a feature, action, or possession that members of the culture understand to be stably associated with the deity.

|

|

|

|

| Nut and Geb. (11th C BCE). Papyrus. | Osiris with Isis. (c 1300). Wall relief. | Isis. (c 570-526). Statue. | |

| Deity | Nut: god of the sky

Geb: god of the earth |

Osiris: brother of Isis, resurrected from the dead, lord of underworld | Isis: rescuer of her brother from death |

| Attribute | Nut conventionally shown arcing over a reclining Geb | A crown suggesting authority | 1) a throne symbol or 2) the horn and solar disc of her daughter Hathor |

|

|

|

|

| Anubis. (c 1478-1458). Sculpture | Thoth (c 1300 BCE). Wall Relief | Hathor offers Menat necklace to Seti I (1200s BCE). Wall relief. | |

| Deity | God who leads the dead to the afterlife | God of scribes and writing | Daughter of Isis |

| Attribute | The head of a jackal | The head of an ibis | Cow’s horns cradling a solar disk |

Form

OK. So a representational work of art depicts a visual subject. The question is, how?

That Nile Style

Style: a consistent pattern of choices regarding form and technique that comprise an identity for an artistic tradition, movement, or individual vision.

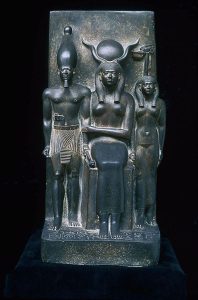

Statues of Pharaohs and their Queens were intended to do more than commemorate. They also served as receptacles for the ka, or life spirit of the individual. The figures below represent Pharaoh Menkaura with his wife and with patron deities. Now how do they do that. What do you notice about the style?

|

|

| Menkaura, Hathor, Hare. (26th C. BCE). | King Menkaura & queen. |

Well, we see figures standing erect, feet flat with one advanced, the king’s arms straight with fists clenched. The faces are impassive and impersonal, capturing no emotion or individuality. Are you surprised? Probably not. The idiosyncratic Egyptian style is so widely known that, in 1986, a pop group called the Bangles had a minor hit with a tuned called “Walk like an Egyptian.”

This distinctive style can be seen in thousands of works of art. Remarkably, it remained all but unchanged for 2,500 years. Dynasty after dynasty, generation after generation, Egyptian artists made consistent choices about the long lean bodies of the their figures and how they should stand or sit. Clothing, facial features, and demeanors are interchangeable with little indication of the individual. These are not portraits, but, rather, Conventional depictions of a generic idea of “the Pharaoh.”

Again we run up against the cultural gap. What is wrong with these artists? 2,500 years and no one thought to try a little innovation, show a little creativity?

But those are our values, right? These days, artists make names for themselves by innovating “original” styles. That’s what Silverman was warning against. The role of the Egyptian artist was not to innovate forms or to express personal vision. It was to support the ideology of a powerful state and to preserve the current way of life, of life itself from the destructive forces of time. Pharaohs came and went, but the image and concept of The Pharaoh lived on through the ages. A stable, unchanging style embodied the ideological heart of a people.

To Imitate or to Stylize?

So representational art depicts visual subjects. Obviously, it does so by emulating the appearance of the subject. We depict a human figure with two arms, legs, eyes, and a mouth.

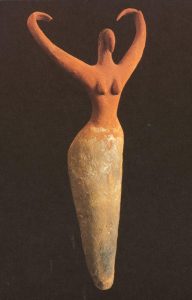

But how much detail do we need? How perfectly must the representation match the dimensions, the textures, the colors of the “real thing”? Consider these examples of Predynastic art before the Pharaohs.

|

|

|

| Figurine of a man. (c 3650-3450 BCE). Elephant ivory | Woman with Upraised Arms. (c 3650-3300 BCE). Terracotta with white paint. | Figurine of a Bearded Man (c 3200-3100 BCE). Breccia composite. |

Well, we can “see” the intended subjects, right? Features in the figurines clearly designate enough human features to evoke a face or a profile. But the level of detail is pretty low, eh? And the proportions, the textures, the colors … not very natural, are they? Let’s make a distinction:

Spectrum of Representational Technique

Imitative depiction:representation that strives to emulate the appearance of the visual subject |

<—-> |

Stylized depiction:representation that simplifies or distorts the appearance of the visual subject and relies on conventional association rather than imitative precision |

Let’s be clear: this distinction is a spectrum, not a choice between distinct alternatives. Images can be more or less imitative and more or less stylized. Indeed, all representational images combine the two forms of effect. And let’s not fall into the trap of labeling Predynastic art as “primitive.” Technologies may evolve, but as we saw in those Ice Age caves, art from distant cultures can be far more richly meaningful than they might appear to outsiders.

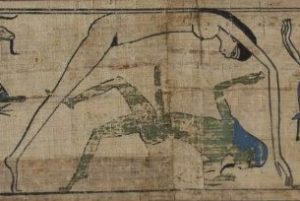

Still, the conventional style of the dynastic periods is considerably more elaborate than the earlier forms. Details, proportions, colors and forms in paintings of the dynastic periods are sophisticated and naturalistic. But there is something a bit odd there. Consider the figures of the two hunters:

Fowling Scene. (c 1400 BCE). Fowling Scene. (c 1400 BCE). |

What is it about those profiles that seems somehow “off,” at least to our eyes? Look especially at the shoulders in comparison with the feet. And what about those eyes?

The issue here is not a matter of ill-developed drawing technique. Rather, these painters established a conventional solution to the problem of showing three dimensions in a two-dimensional format. Figures are shown in profile, i.e. from the side. But shoulders, chests, and eyes are shown face-on. These hybrid points of view are skillfully integrated into elegant unities of form.

Pure Form

At this point, let’s try to clarify what we mean by form, a term that, like many others in in the arts, can be used in different ways. We have been exploring Egyptian art as a representation of visual subjects and as a signifier of contextually grounded meaning. But art can be viewed on a more elemental level.

Form (generic): in the arts, a term referring to the elements, patterns, and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

Formal elements: in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any representation of a visual subject: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement

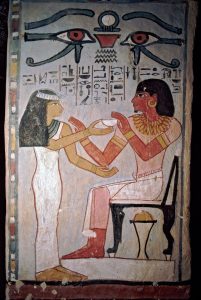

Let’s look at the painting of Meryt conferring authority on Sennufer. And let’s ignore the people, the history, the culture, the cultural significance. Indeed, let’s forget that we are looking at the depiction of human figures. What visual features do we see disconnected from any other thoughts?

Meryt offers cup to Sennufer. (c 1410 BCE). Wall painting. Meryt offers cup to Sennufer. (c 1410 BCE). Wall painting. |

In the upper register, we see two of visual art’s most elemental features: line and color. Curved—curvilinear—lines stretch across the frame of the painting and form another formal element: shapes, including oval-circle combinations that we read as eyes but are in themselves geometrical shapes common to many cultural traditions. The human figures are shaped with elegantly stretched, curvilinear contour lines. These forms feature a limited color palette of black and earth tones, muted yellow and red formed from ochre.

Looked at from this formal perspective, representational issues fade in significance. Legs, ankles, and feet are not particularly detailed, but they flow elegantly into the columnar assembly of rectangular and triangular shapes. If we step back from the What is it? question, we can experience these formal elements as an integrated visual composition. Whether or not we realize it, formal elements such as Line, Shape, Color, Texture, and Composition contribute seminally to our sense of beauty.

References

Abu Simbel. Temple of Ramses II. (c 1270 BCE). Facade: Four Colossi of Ramses II. Delso, Diego. (April 2, 2022). Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Templo_de_Rams%C3%A9s_II,_Abu_Simbel,_Egipto,_2022-04-02,_DD_03.jpg

Anubis [Statue]. (7th C BCE). Minneapolis , MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. 16.35 https://collections.artsmia.org/art/90/figure-of-god-anubis-egypt Bronze

Book of the Dead of Hunefer [Papyrus Scroll]. (c 1300 BCE). London, UK: British Museum: EA9901,3 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA9901-3

Canon of Proportion [Drawing board]. (c 1550-1292 BCE). London, UK: British Museum, AN EA5601. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA5601

Curran, A. (c 1820). Portrait of Percy B. Shelley [Painting]. London, UK: National Portrait Gallery. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw05763/Percy-Bysshe-Shelley?LinkID=mp06843&search=sas&sText=Amelia+Curran&role=art&rNo=0

False Door—Tomb Wall [Relief]. (c 2400 BCE). Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of art https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1230/false-door-ancient-egyptian

Figurine of a Bearded Man (c 3200-3100 BCE). Rama. [Photograph]. (April 19, 2011). Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Predynastic_bearded_man-MGR_Lyon-IMG_9928.jpg Breccia composite

Figurine of a man. (c 3650-3450 BCE). New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. AN 54.28.2. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547233 Elephant ivory

Fowling Scene [Painting]. (c 1400 BCE). Luxor, E.G.: Tomb of Nakht. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548578 Tempera on Paper

Frith, F. (1860). Statues of Memon, First View [Photograph, Albumen Print]. New York, NY: New York Public Library Digital Collections https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/16ff9dc0-c6e1-012f-1c1d-58d385a7bc34#/?uuid=510d47d9-5c7a-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Frith, F. (1860). The Great Pyramid and Sphinx [Photograph, Albumen Print]. Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. AN 1998.42.3.17. https://www.clarkart.edu/ArtPiece/Detail/The-Great-Pyramid-and-the-Great-Sphinx,-from-the-s

Funerary Model Boat (c 2100-1780 BCE). Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, AN AIC_.1894.241 https://www.artic.edu/artworks/127874/model-of-a-river-boat Wood and pigment

Funerary Papyrus of Tameni. (11th C BCE). London, UK: British Museum: EA10008,3. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA10008-3

Grape Harvest [Wall Painting]. (13th C BCE). Thebes, E.G.: Tomb of Khaemweset, No 261. Wine of Ancient Egypt https://wineofancientegypt.com/upper-egypt/western-thebes-dira-abu-el-naga/tomb-of-khaemwaset

Hathor offers Menat necklace to Seti I [Relief]. (1290-1279 BCE). Florence, IT: National Archaeological Museum of Florence. https://museoarcheologiconazionaledifirenze.wordpress.com/?s=Hathor

Hunting scene [Painting]. (c 1400 B.C.). Thebes, E.G.: Tomb of Menna. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Archive for Research on Archetypal Symbolism. ON 30.4.48. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548437

Isis [Statue]. (c 570-526). Cairo, Egypt: The Egyptian Museum. https://egyptianmuseumcairo.eg/artefacts/greywacke-seated-statue-of-isis/

King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and queen [Sculpture]. (2490-2472 B.C.). Boston, MA: Museum of Fine Arts. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/230/king-menkaura-mycerinus-and-queen?ctx=3672cc6f-0a30-490e-a7f0-41eda054e603&idx=5

King Menkaure (Mycerinus), the goddess Hathor, and the deified Hare nome [Sculpture]. (2532-2510 B.C.). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/138424/king-menkaura-the-goddess-hathor-and-the-deified-hare-nome?ctx=3672cc6f-0a30-490e-a7f0-41eda054e603&idx=6

Meryt offers cup to Sennufer [Wall painting]. (c 1410 BCE). Thebes, E.G.: Tomb of Sennufer. Brodkey, A K. [Photograph. (1979). Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.11893499

Narmer Palette [Slate relief]. (ca. 3150 BCE). Cairo, E.G.: Egyptian Museum. https://egyptianmuseumcairo.eg/artefacts/narmer-palette-collection/

Nut and Geb. [Detail]. (11th C BCE). Funerary Papyrus of Tameni. London, UK: British Museum: EA10008,3. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA10008-3

Osiris with Isis and Nepthys [Detail]. (c 1300). Hunefer Book of the Dead. London, UK: British Museum: EA9901,3 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA9901-3

Shelley, P. (January 11, 1818) “Ozymandias.” London: The Examiner. Retrieved from Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69503/percy-bysshe-shelley-ozymandias#poem

Silverman, D. P. (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thoth [Relief]. (c 1300 BCE}. Abydos, Egypt: Temple of Seti I. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/Thoth/

Woman with Upraised Arms [Figurine]. (c 3650-3300 BCE). Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum of Art. AN 07.447.505 https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/objects/4225 terracotta enlivened with traces of white paint on lower half.

the situation of a work of art in a cultural, historical, or personal setting which shapes media, materials, techniques, and meanings for the artist and also the audience

a slab, usually of stone, that marks a grave or boundary and commemorates the authority, victories, and achievement of a ruler or a regime

a quality of art that instructs its audience on information, ways of life, or social, moral, religious, or political principles

a function of visual art which seeks to emulate a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

in visual art, the figure or scene conveyed by the composition, e.g. a land-scape, an individual in a portrait, a dramatic scene, a person in a portrait

1) an image which signifies a holy figure for worship or devotion. 2) a Christian image of Jesus or saints which focuses worship and prayer. 3) a Byzantine genre of holy mosaics and paintings that depicts holy figures according to a conventional style. 4) In contemporary scholarship, an image that signifies a conventional meaning recognized by an audience despite the absence of any visual resemblance.

a standard feature of art in a given genre that is expected and understood in the context of origin: e.g. a content, a style, a signification, a theme

a detail of appearance or associated possession that conventionally identifies a saint, deity, or other exalted personage in an iconography

a consistent pattern of choices regarding form and technique that comprise an identity for an artistic tradition, movement, or individual vision

an aspect of art which is expected and understood by the audience in a particular tradition

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

in visual art, a 2-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth. Line may be straight or curved, directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

a visual subject’s quality or wavelength of light. Three primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—combine to form secondary hues: orange, green, purple. Complementary colors create enhanced aesthetic resonance when placed against each other. Components of color include Hue, Value, Saturation (intensity) and Temperature.

in visual art, a two-dimensional figure with a more or less defined border displaying only height and width

in visual art, the illusion of surface feel either of A) the represented object (e.g. textures of clothing) or B) of the artifact’s media (e.g. canvas weave, brushstrokes, daubs of paint)

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc