1.4 Art of Hindu Devotion

Shiva as Lord of the Dance. (500-1000 CE).

Shiva as Lord of the Dance. (500-1000 CE).

Hindu art is the product of one of the world’s great religions. … Their art is primarily devotional, encouraging them to acknowledge the presence of a god or gods. … Almost all Indian art has, until recently, been religious in inspiration (Blurton, 1993, pp 9-10).

Another great tradition of art from the ancient world is that of the Hindu civilization which arose around 3,500 years ago. Blurton stresses that Hindu art focuses almost exclusively on the faith that thrives today in India and many other regions of the world.

Let me confess. When I approach Hindu art, I bring very little knowledge of Context to the table. I need to follow our process:

Approaching Unfamiliar Art

- Hold one’s initial responses loosely, opening to fresh perspectives.

- Notice indicators of cultural gaps: might that feature mean something else in the culture of origin?

- Gather whatever background information is available.

- See the works afresh in light of what has learned.

- Make an honest assessment of how you wish to respond.

Let’s draw on Richard Blurton’s expertise and try to make sense of what we see.

Earth, Temple, Ritual

Hindu art offers an interesting comparison with the ancient Egyptian tradition. Both are focused intensely on religious themes. However, while Egyptian art was absorbed with the journey of the deceased into the afterlife, Hindu art, as noted by Blurton, is primarily devotional, encouraging personal prayer and worship. The word bhakti refers to the Hindu commitment to devotion, expressed in pilgrimage and worship in shrines (Blurton, p. 36).

The fascinating intersection of religion, art, and architecture in temples and churches is beyond our scope for the course. I personally love to explore the tradition of great churches, especially in the Gothic era. But a brief peek at Hindu temples can point up the close linkage between art and ideology.

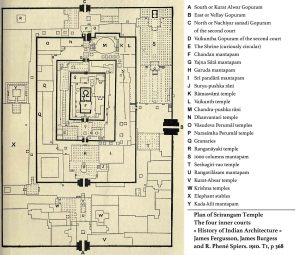

As is true in many ancient cultures, the Hindu temple was thought to be the residence of the god. It was also a place designed to guide worshipers in their devotional rituals. Holy texts called shastras prescribed the design of the temple and the practices of the ritual (Blurton, 44).

|

|

|

| Chaturbhuj Temple. (16th C BCE). Orchha, Madhya Pradesh, India | Plan of Hindu Temple. (1910). | Mandala of Vairocana. (11th C). Alchi Buddhist Monastery Complex. Ladakh, Jammu, and Kashmir State, India. |

Rituals and temples are designed to represent the cosmography of the faith. On a two-dimensional, domestic level, the mandala design represents the universe, with the god residing at the center. The temple is conceived as a three-dimensional, large-scale Representation of the faith cosmography (Blurton, pp. 47-48).

Avatars and Attributes

Like most ancient religious traditions, Hindu faith worshiped a wide array of deities. The theology is made even more complicated by the notion of avatars, incarnations or “forms of the god manifesting themselves (‘descending’) to mankind at times of great need” (Blurton, p. 34). The major deities, Shiva, Vishnu, and Devi have been represented and worshipped in many forms.

The Hindu worshiper, therefore, faces a devotional challenge in keeping it all straight. Hindu visual art functions as a theological reference resource. One who views Hindu art, whatever one’s faith perspective, faces the challenge of grasping the Conventional Signification of an ideological system:

Icon: an image which signifies specific religious content for devotion and ritual

Iconography: a system of significations that are conventionally associated with designated symbols that link figures with detailed attributes

Attribute: a detail of appearance or associated possession that conventionally identifies a saint, deity, or other exalted personage in an iconography

Our ever so brief look at Hindu iconography can also serve as an object lesson in how to approach similar conventional systems from other religions. As we begin, let’s just note the attribute of the multiple arms and hands of the gods, a convention signifying the manifold and superhuman powers of the divine.

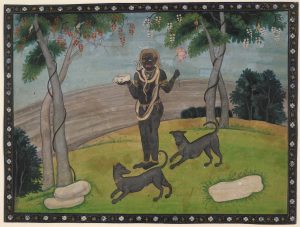

Shiva

Shiva, a popular and powerful deity, combines a variety of characteristics: playful and outrageous, yet pious and ascetic. Wed to Devi, the Great Goddess, he represents the force that gives life. Shiva’s fertility is characterized as a divine dance that leads the rituals and arts of Hindu devotion.

|

|

| Shiva as Lord of the Dance. (500-1000 CE). | Shiva as Bhairava. (c 1820). |

Shiva’s incarnation as Bhairava both aligns with and challenges Christian tradition. Shiva is associated with the ascetic life of the mendicant holy men who renounced the world and sought truth. Thus, his image often bears ascetic attributes: emaciated skin darkened by ashes, wild, uncombed hair, ritual beads around the neck, and the skull that holy men used as a begging bowl for alms (Blurton, pp. 87-88). Of course, the Christian tradition is familiar with the lives of mendicant ascetics, but the monastic tradition was committed to celibacy, not fertility.

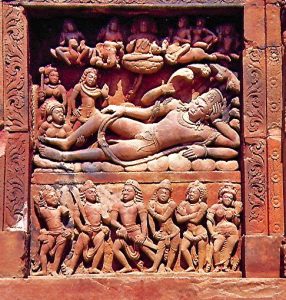

Vishnu

Blurton characterizes Vishnu as a mediating force preserving the ordered world, the home, domestic order and affections, and the cosmic “intervening time that stretches between the Beginning and the End” (pp. 111ff). He lists as conventional Attributes a regal crown, contrasting with Shiva’s ascetic hair, and four hands holding a lotus flower, a conch shell, and two weapons, a club and a chakra, or discus (p. 115).

|

|

|

| Vishnu. (c 10th-11th Century CE). Gilt-copper alloy. | Vishnu Dreaming upon the serpent-bed of Shesha. (6th C CE). Dashavatara Temple. | Krishna lifting up Mount Govardhan. (c 1690). Gouache painting on paper. |

As the ground on which the current world is supported, Vishnu is thought to sustain reality through a divine dream. Shesha, the serpent who bears the planets and heavens persists in Vishnu’s dream. Krishna, one of Vishnu’s many avatars, is said to have lifted Mount Govardhan and held it over the people’s heads to protect them from the wrath of the god Indra.

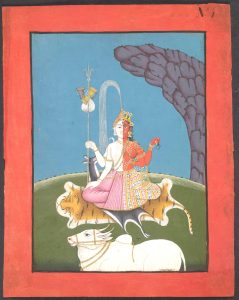

Devi, the Great Goddess

Devi, the Great Goddess of Hindu faith, embodies the union of water and soil which bring forth life. As Parvati, the consort of Shiva, she represents the fertility of the family. Shive and Devi/Parvati are often pictured together or even fused into one being, Ardhanarishvara.

|

|

| Shiva and Parvati. (c 800 CE). Relief. | Ardhanarīśvara. (1790-1810). |

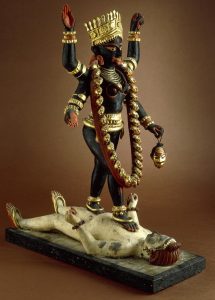

In her numerous avatars, Devi represents action. She is associated with “blood, alcohol, and fertility.” “Fickle and dangerous,” says Blurton, “she inflicts harm and yet also protects from it” (p. 165). As Durga, she slays the Buffalo Demon and other evils. Her attributes as Kali include a necklace of skulls and a tongue red with sacrificial blood (Blurton, p. 173). The common image of a ferocious Kali standing above a recumbent Shiva remembers an incident in which the Lord of the Dance lay down in surrender to lead her back from a lethal rage in which she had killed many demons.

|

|

| Devi Uma Parameshvari. (c 950 CE). | Kali standing over recumbent Shiva. (19th Century CE). |

Clearly, the Hindu concept of the female has many dimensions, some which seem to be Paradoxes of nurture and destruction. The testimony of world art tells us that women have fulfilled many roles not necessarily recognized in European and American tradition.

Vital Questions

Context

We have, of course, sampled the merest fraction of the Hindu tradition. Like the Christian and unlike the ancient Egyptian, that tradition remains vibrant and productive today, a treasured form of expression for a faith shared by millions world-wide. Thousands of Americans share that tradition, and it may be that some are members of this class.

By sampling this tradition, we learn a great deal about art in general and religious art in particular. We see that the Museum Function forms only a small and recent share of world artistic history. Parietal art. Ancient Egyptian art. Hindu art. Each of these traditions is committed to Spiritual goals which must at least be roughly comprehended if one is to understand.

The Hindu tradition can also lay down a conceptual foundation for exploring Christian art. As we shall see, Christian Icons depict saints and martyrs, each identified with distinctive Attributes.

Content

While we can recognize parallels between Egyptian, Hindu, and Christian artistic Conventions, we can also see differences. Like Christian Icons, Hindu art is emphatically devotional, seeking union with the divine. Yet Christians find the multiple gods and avatars confusing and contrary to the Christian belief in a single God. Nevertheless, the Content of both traditions shares a similar Function: Representations of human figures and associated Attributes hold Significations that are shaped by firm religious Convention.

Form

We will consider the Styles and Forms of Christian art later. For now, let’s just note the difference between Egyptian and Hindu style. Egyptian art was largely static, Stylized, fixing human figures in timeless poses split between profile and face on Perspectives. Hindu art is more fluid, more active. Its sweeping, curvilinear forms have a robust liveliness that Egyptian figures lack. As a living art form, Hindu tradition has evolved and developed, contemporary compositions investing the traditional doctrines into forms that seem at home in our world today. As we go forward, let’s continue to distinguish between expressive Content and Aesthetic Form.

References

Ardhanarīśvara [Painting]. (1790-1810). London, UK: British Museum. Accession 1880,0.2166 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1880-0-2166

Bahsoli School. (17th Century CE). Holy Man Prostrated before Krishna/Vishnu [Ink Drawing]. (17th C). Virtual Museum of Images & Sounds. https://vmis.in/ArchiveCategories/collection_gallery_zoom?id=491&search=1&index=30919&searchstring=krishna/vishnu

Blurton, T. R. (1993). Hindu Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chaturbhuj Temple. (16th C BCE). Orchha, Madhya Pradesh, IN: Welch, S. (December 13, 2021). Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:0121321_Chaturbhuj_Temple,_Orchha_Madhya_Pradesh_002.jpg

Devi Uma Parameshvari [Sculpture]. (c 950). Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1984.2

Kali standing over recumbent Shiva [Sculpture]. (c 19th C.) London, UK: British Museum. Accession 299965001. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1894-0216-10

Krishna lifting up Mount Govardhan [Painting.] (c 1690). London, UK: British Museum, AN 1960,0716,0.16 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1960-0716-0-16

Mandala of Vairocana. (11th C). Alchi Buddhist Monastery Complex. Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir State, IN: John C. and Susan L. Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art. https://dsal.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/huntington/show_detail.py?ObjectID=30023563

Plan of Temple [Print illustration]. (1910). Fergusson, J., Burgess, J. and Spiers, R.R. and R. P. Spiers. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, p. 368. Ismoon. (2/1/2017). Jpeg file. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plan_of_Srirangam_Temple._Burgess,1910.jpg

Plan of Temple [Print illustration]. (1910). Fergusson, J., Burgess, J. and Spiers, R.R. and R. P. Spiers. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, p. 368. Ismoon. (2/1/2017). Jpeg file. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plan_of_Srirangam_Temple._Burgess,1910.jpg

Shiva as Lord of the Dance [Sculpture]. (500-1000 CE). Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Accession number M.75.1. https://unframed.lacma.org/2015/03/02/collection-shiva-lord-dance

Shiva as Bhairava [Painting]. (c 1820). London, UK: British Museum. Accession 1925,1016,0.16 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1925-1016-0-16

Shiva and Parvati [Relief]. (c. 800 CE). London, UK: British Museum. Accession 2017,3050.1. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_2017-3050-1 Sculpted slab of green chlorite depicting standing three-headed Shiva (Maheshvara) and his consort, Parvati; they are both haloed.

Vishnu [Sculpture]. (c 10th-11th Century CE). Nepal: Thakuri period. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. AN 38326. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/38326

Vishnu Dreaming upon the serpent-bed of Shesha [Relief]. (6th Century CE). Deogarh, India: Dashavatara Temple. King, B. [Photograph]. (29 November 2007). Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anantasayi_Vishnu_Deogarh.jpg

the situation of a work of art in a cultural, historical, or personal setting which shapes media, materials, techniques, and meanings for the artist and also the audience

an aspect of art which is expected and understood by the audience in a particular tradition

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

A conventional system of significations that associate details of appearance with particular religious figures

a detail of appearance or associated possession that conventionally identifies a saint, deity, or other exalted personage in an iconography

a trope in which two terms in a statement seem contradictory but suggest an elusive point: e.g.: “the child is father of the man (William Wordsworth, “My Heart Leaps Up, 1802).

the assumption that paintings and sculptures are intended to be displayed for public reflective viewing by people who seek beauty, ideas, and interesting experiments in vision

1) an image which signifies a holy figure for worship or devotion. 2) a Christian image of Jesus or saints which focuses worship and prayer. 3) a Byzantine genre of holy mosaics and paintings that depicts holy figures according to a conventional style. 4) In contemporary scholarship, an image that signifies a conventional meaning recognized by an audience despite the absence of any visual resemblance.

the material projected by art for the reader’s mind and imagination. Content can consist of an immediate Subject—e.g. a figure in a painting or a story in a narrative—and Signification, a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature

the intended role which a work of art was designed to play and its influence on that work’s form

a function of visual art which seeks to emulate a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

a standard feature of art in a given genre that is expected and understood in the context of origin: e.g. a content, a style, a signification, a theme

a consistent pattern of choices regarding form and technique that comprise an identity for an artistic tradition, movement, or individual vision

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

a representational technique that depicts the idea of a visual subject through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis

in visual art, the illusion of 3-dimensional forms and spaces in 2-dimensional compositions by aligning and scaling forms to suggest depth and distance.

the dimension of an artistic experience that appeals to or challenges an au-dience’s sense of taste and experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A response distinct from “interested” concerns such as ideology, sexuality, social conflict or economics