8.3 The Renaissance in England

Have you ever wondered about this English language we are reading and writing in? Where did it come from? Why does it seem to share a lot of vocabulary with German and French? Why are its verb forms so inconsistent? Why is its spelling so appallingly erratic?

Without taxing your patience too far (I hope!) we can mention the 5th and the 11th Centuries. As Roman legions withdrew from Britain in the 5th Century, Germanic peoples invaded or migrated (?) across the North Sea. As they gained control, the dialect of the Angles and Saxons—Anglo=Saxon—gained dominance.

Then, in 1066, the Norman French Duke William invaded and wrested control from the Anglo-Saxons. For 300 years, aristocrats spoke French, the common people spoke Anglo-Saxon, and the learned wrote and spoke Latin. Mix the languages and you get Early Modern English, the language we all strive to master. You can see the heritage of German, French, Latin, and a little Greek. Consider “silent gh” words: brought, night, weight, height, and many more. All are descended from German which would have voiced the “ckhhh” sound.

Early Modern English settled in during the 15th Century, just in time for the 1st glory days of English Literature. In England, the Renaissance was late and it was primarily a matter of writing.

The literary flowering known as the English Renaissance occurred during the realm of Queen Elizabeth I, daughter of the infamous Henry XII whose Tudor dynasty was subject to question after the Wars of the Roses. Elizabeth returned England to the Protestant Church of England that was established by her father, making herself the enemy of all of Catholic Europe. So, let’s see: Questionable dynasty. Protest. And, of course, a woman in a world in which women did not rule. Can you see some vulnerabilities?

The Shakespearian Stage

|

| William Shakespeare. (1623) To the Reader. Frontispiece, 1st Folio. |

Elizabethan literature blossomed primarily on stage. Companies of players toured from one country estate to another and always back to town—London—to perform masterpieces of Elizabethan drama. Leading lights of the Elizabethan stage included Ben Jonson, Christopher Marlowe, and Thomas Kydd. But of course, we think of William Shakespeare, the great light of English or perhaps world literature. Shakespeare acted, directed, and managed a company and the London Globe theater. He also wrote some scripts.

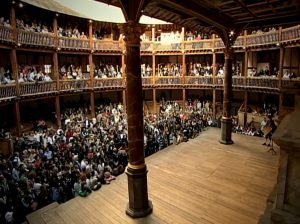

|

| Modern Globe Theater. (2007). Film still from Othello. |

Shakespeare is thought to have written 37 plays. These dramas fit surprisingly well into Aristotle’s categories in Poetics. Let’s briefly sample key speeches from three characteristic Shakespearian dramas.

Epic Histories

For Aristotle, the Epic is a long, episodic narrative far too expansive for the stage. However, if we think of Homer’s epics as patriotic chronicles of the Greek peoples’ destiny, Shakespeare’s histories seem to fit.

In the 15th Century, artists and writers required sponsorship from an aristocratic or royal patron. Given the vulnerabilities of Elizabeth’s court, you can imagine the importance of a patriotic orientation. Shakespeare’s eleven histories chronicle a succession of British monarchies. They roughly support the Tudor claims to authority. And they do much, much more.

A series of 3 plays—Henry IV, part 1, Henry IV, part 2, and Henry V—explore a tumultuous time in British history: the struggles between the Norman French kings of England and the French kings in Paris for control of France. Henry V follows young Prince Hal as he overcomes youthful follies and leads an army into France at the opening of the Hundred Years War.

The play reaches its climax in the Battle of Agincourt in which Henry’s small army routed a massive force of heavily armored French knights. English yeomen, common soldiers and experts with the long bow, cut down the highborn French knights from afar. To this day, the British revere the victory at Agincourt.

As the battle began, however, things looked bad for the small British army. Henry’s stirring speech inspires his soldiers and continues to inspire soldiers and athletes even today. Every time you see the phrase “band of brothers,” Shakespeare’s words live on.

from Henry V, Act 4, Scene 3

HENRY If we are marked to die, we are enough

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honor.

God’s will, I pray thee wish not one man more. …

Rather proclaim it, Westmoreland, through my host,

That he which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart. His passport shall be made,

And crowns[1] for convoy put into his purse.

We would not die in that man’s company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

This day is called the feast of Crispian.[2]

He that outlives this day and comes safe home

Will stand o’ tiptoe when this day is named

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall see this day, and live old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbors

And say “Tomorrow is Saint Crispian.”

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day. Then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words,

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester,

Be in their flowing cups freshly remembered.

This story shall the good man teach his son,

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be rememberèd—

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,[3]

This day shall gentle his condition;[4]

And gentlemen in England now abed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

[1] Crowns: i.e. royally endorsed coins of high value

[2] Crispin’s day: the calendar of the medieval church listed many holy days (holidays) that honored various saints. Crispin and Crispian were Christians martyred during the 3rd Century persecutions of Diocletian

[3] Vile: this word refers to social caste—the sense is no matter how low of birth.

[4] Gentle his condition: think of gentleman—the word gentle refers to a rank within the aristocratic upper classes. Henry is saying that veterans of this battle will rise to a higher social caste.

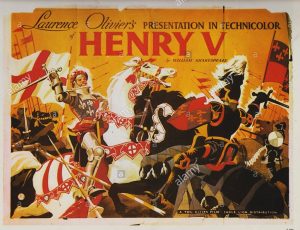

|

| Lawrence Olivier. (1944). Henry V: film poster. |

The play has twice been notably filmed. Lawrence Olivier directed and starred in a 1944 production to rally English spirits during World War II. View this YouTube film clip of Olivier’s brilliant performance.

Eloquent Tragedy

What can you recall of Aristotle’s definition of Tragedy? A Plot in which a Tragic Hero comes to a grievous end through a series of logically connected events driven by the Protagonist’s Tragic Flaw.

Lear is an aging king brought to ruin by fatuous vanity. Thinking to retire, he foolishly divides his kingdom between his three daughters. Two daughters vie with each other to pile on outrageously grandiloquent flattery. When his third daughter, Cordelia, offers simple devotion, Lear angrily disinherits her.

To only Lear’s surprise, the flatterers turn out to be heartless liars who turn him out. In an incandescent scene, a mad Lear wanders onto an open heath during a thunderstorm. Driven mad by impotent rage at his daughters and the crushing storms of fate, Lear howls with rage.

|

| George Frederick Bensell. (19th C). King Lear. Oil on canvas. |

from King Lear, Act 3, Scene 2

LEAR Blow winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drenched our steeples, ⟨drowned⟩ the cocks.[1]

You sulph’rous[2] and thought-executing[3] fires,

Vaunt[4]-couriers of oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head. And thou, all-shaking thunder,

Strike flat the thick rotundity o’ th’ world.

Crack nature’s molds, all germens[5] spill at once

That makes ingrateful man. …

Rumble thy bellyful! Spit, fire! Spout, rain!

Nor rain, wind, thunder, fire are my daughters.

I tax[6] not you, you elements, with unkindness.

I never gave you kingdom, called you children;[7]

You owe me no subscription.[8] Then let fall

Your horrible pleasure. Here I stand your slave,

A poor, infirm, weak, and despised old man.

But yet I call you servile ministers,

That will with two pernicious daughters join

Your high-engendered[9] battles ’gainst a head

So old and white as this. O, ho, ’tis foul!

[1] Cocks: weather vanes on buildings, often shaped as cockerels. The sense is a flood so great that images of cocks would be drowned.

[2] Sulph’rous: that is drenched in the smell of burning sulfur, a stench associated with hell

[3] Thought-executing: i.e. destroying one’s ability to think

[4] Vaunt: i.e. vain, vainglorious

[5] Germens: i.e. germs, minute organisms

[6] Tax: i.e. accuse. The sense is, “I do not accuse you elements of unkindness.”

[7] The contrast here is between the elements and Lear’s unfaithful daughters.

[8] Subscription: i.e. you elements are not responsible to reward the blessings I bestowed on my daughters.

[9] High-engendered: i.e. destined and devised from on high, heaven-ordered fate

The tragedy rolls on for two more acts, ending in deaths deriving from Lear’s folly and the machinations of Edmund, one of Shakespeare’s great villains. I invite you to witness Paul Schofield’s performance of the scene in Peter Brooks’ production of King Lear.

Shakespeare’s Comic Muse

As You Like It, one of Shakespeare’s most popular comedies, follows the formula of farce: romance, disguised identities, interplays between high and low social castes. The character of Jacques matches the role of a Greek chorus, commenting on the activities without participating in any action. In the 2nd act, Jacques builds a comprehensive view of human life on the metaphor of life as the performance of a part on stage.

from As You Like It, Act II, Scene vii

JACQUES All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players.[1]

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling[2] and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then the whining schoolboy with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,[3]

Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,[4]

In fair round belly with good capon[5] lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon[6]

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank,[7] and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans[8] teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

[1] Players: i.e. actors.

[2] Mewling: i.e. whimpering, crying weakly

[3] Pard: or pardoner, a priest who sold indulgences said to purify sinners from their sins

[4] Justice: a metaphorical man of law or magistrate dispensing wisdom with the authority of mature adulthood

[5] Capon: i.e. chicken

[6] Pantaloon: a stock character in folk comedies, a foolish, mean character known for wearing spectacles and tight trousers

[7] Shank: i.e. leg

[8] Sans: French for without

Paul Czinner. (1936). As You Like It [Film poster]. 20th Century Fox. Paul Czinner. (1936). As You Like It [Film poster]. 20th Century Fox. |

| View Leon Quartermaine’s 1936 performance as Jacques delivering the famous speech. |

References

Bensell, George Frederick. (19th C). King Lear [Painting]. The Knoll Collection. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:King_Lear_by_George_Frederick_Bensell.jpg

Czinner, Paul. (1936). As You Like It: Act II, scene vii [Film clip]. 20th Century Fox. Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qk_rPHoSc8w

Czinner, Paul. (1936). As You Like It [Film poster]. 20th Century Fox. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:As_you_like_it_ii.jpg

Modern Globe Theater [Film still]. (2007). Othello. [Film]. Films on Demand. Available at https://fod-infobase-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/p_ViewVideo.aspx?xtid=145211

Olivier, L. (1944). Henry V: Act IV, scene iii [Film clip]. UK: Two Cities Film

Olivier, L. (1944). Henry V: [Film poster]. UK: Two Cities Film. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Henry_V_%E2%80%93_1944_UK_film_poster.jpg

Brook, Peter. (1971) King Lear: Act III, scene ii. Royal Shakespeare Company. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xi0xmaBgjDk

Shakespeare, W. (1597). As You Like It. (B. Mowat, P. Werstine, M. Poston, and R. Niles, eds.). The Folger Shakespeare As You Like It – Act 2, scene 7 | Folger Shakespeare Library

Shakespeare, W. (1597). Henry V. (B. Mowat, P. Werstine, M. Poston, and R. Niles, eds.). The Folger Shakespeare https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/henry-v/read/4/3/

Shakespeare, W. (c 1606). King Lear. (B. Mowat, P. Werstine, M. Poston, and R. Niles, eds.). The Folger Shakespeare https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/king-lear/read/3/2/?q=Crack#line-3.2.1

Shakespeare, W. (1623) To the Reader. [Frontispiece, 1st Folio]. New Haven, CT: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Title_page_William_Shakespeare%27s_First_Folio_1623.jpg

an extended, mythic narrative celebrating the trials and triumphs of heroes exemplifying a culture’s treasured values and orienting its origins

according to Aristotle, a drama which inspires pity and fear when a hero we care about comes to a bitter end that grows out of a tragic flaw (hamartia)

a meaningful sequencing of story events that builds suspense through conflict and rising tension culminating in a climactic resolution

a protagonist who comes to a grievous end because of a tragic flaw which leads logically and inexorably through the events of a plot

(or Hero) the rival in a story’s agon (central conflict) with whom we positively identify and sympathize

the fault of character in an otherwise worthy hero which triggers a chain of events ending in the character’s doom