8.2 The Vernacular Renaissance

The six poets in Vasari’s painting had something in common. Something apparently banal. They wrote great literary verse … in Italian. No surprise, right?

And yet, in Dante’s time, this was shocking. Throughout Europe, almost everything was written in Latin, the language of church scholarship. Serious poetry had to be written in Latin. Folk tales and popular ballads were told and sung in the languages of the people, but nobody took that peasant fare seriously.

But what language did the people, very, very few of whom could speak or write Latin, speak? “Italy” did not exist as a country. The peninsula was divided into separate feudal states and republics. Each spoke a closely related but distinct vernacular dialect. But then Dante came along.

After the 14th Century, we can speak of Italian literature. Dante and those that followed him composed major poetic works in the Florentine dialect which became the basis for formal modern Italian.

Doing so, they established a precedent for other European literatures which were increasingly composed in the vernacular. Want to be a poet in a Euro-American language today? You don’t have to learn Latin first. You can achieve a literary reputation in the language you speak every day. You have Dante to thank for that.

Dante Alighieri

Dante was born in 1265 in the city of Florence, already a financial and political power and patronage center for scholarship. One day, a nine-year-old Dante looked across the church and fell desperately in love with a lovely eight-year-old named Beatrice. Despite Dante’s claim to have often spotted her from afar, the two virtually never spoke. For the rest of his life, however, the vision of Beatrice haunted Dante’s mind and heart as a holy incarnation of ideal Christian spirit

|

|

| Luca Signorelli. (c 1500). Dante Reading. Cathedral Fresco | Dante Gabriel Rosetti. (1870). Beatta Beatrix. (Dante’s Beatrice) |

The vision of Beatrice inspired Dante’s outpouring of verses written in the Florentine dialect and reveling in love’s ideal passions. In Chapter 3, we touched briefly on a tradition that Dante helped to establish:

Dante’s lyrics are perpetually inspired by his anguished love for Beatrice. Then, in 1290, the woman scholars identify with Dante’s Beatrice died. In that same year he penned a heartbroken lyric which was translated by the English poet and Painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

“Upon a day, came Sorrow in to me” (June 9, 1290)

Translated by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1861)

Upon a day, came Sorrow in to me,

Saying, ‘I’ve come to stay with thee a while’;

And I perceived that she had ushered Bile

And Pain into my house for company.

Wherefore I said, ‘Go forth – away with thee!’

But like a Greek she answered, full of guile,

And went on arguing in an easy style.

Then, looking, I saw Love come silently,

Habited in black raiment, smooth and new,

Having a black hat set upon his hair;

And certainly the tears he shed were true.

So that I asked, ‘What ails thee, trifler?’

Answering, he said: ‘A grief to be gone through;

For our own lady’s dying, brother dear.’

The Divine Comedy

How would you like a detailed account of the thorny papal politics that divided Italy and pitted one faction in Florence against another? Not so much? OK. Let’s leave it at this.

Dante fought on the losing side in a Florentine civil war. In 1302, he was driven into exile from his beloved city. For the rest of his life, Dante was haunted by fever dreams of the dead Beatrice and of the prospect of returning to Florence in triumph.

|

| Domenico di Michelino,. (1465). The Divine Comedy of Dante. Florence, Italy: Cathedral Fresco. |

Somehow, however, Dante transmuted his depression into one of the world’s greatest texts, The Divine Comedy. This massive poem, three books of 33 cantos each, begins with a confession of something a great deal like mental illness. We’ll be sampling the 1814 translation by H. F. Cary which, though dated, has two virtues. It is public domain (no fees!) and it is graced by the wonderful illustrations by the German artist Gustav Dore. (I actually prefer the John Ciardi translation, 1954 to 1970, which is outside our price range.)

from Inferno

from Canto I

In the midway of this our mortal life,

I found me in a gloomy wood, astray

Gone from the path direct: and e’en to tell

It were no easy task, how savage wild

That Forest, how robust and rough its growth,

Which to remember only, my dismay

Renews, in bitterness not far from death. …

How first I enter’d it I scarce can say,

Such sleepy dullness in that instant weigh’d

My senses down, when the true path I left. …

Dante’s imagines his life’s path beset with dangers leading him to despair and destruction. Then he sees a ghostly figure who calls him to a Hero’s Journey. The voice turns out to be the soul of Virgil, the Roman poet whom Dante idolizes. He has been sent by Beatrice, residing in heaven, to lead Dante to faith and life.

Virgil offers Dante a path to salvation, but the way leads first into the gloom and despair of hell—yes, hell, which Dante imagines reaching into the bowels of the earth.

That thou mayst follow me, and I thy guide

Will lead thee hence through an eternal space,

Where thou shalt hear despairing shrieks, and see

Spirits of old tormented, who invoke

A second death; and those next view, who dwell

Content in fire, for that they hope to come,

Whene’er the time may be, among the blest,

Into whose regions if thou then desire

T’ ascend, a spirit worthier than I

Must lead thee, in whose charge, when I depart.”

from Canto III

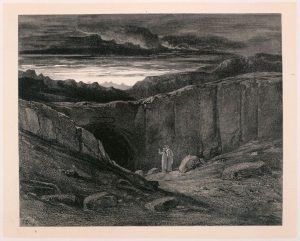

The long dead Virgil resides in what Dante imagines as the first circle of hell, a quiet, relatively painless, but perpetually sad abode of pagans who led virtuous lives but can never find salvation because they were not baptized into Christ’s redemption. Virgil leads Dante into a valley and through gates which warn that those who enter will suffer eternal torments: abandon hope, all ye who enter here.

Through me you pass into eternal pain:

Through me among the people lost for aye.

Justice the founder of my fabric mov’d:

To rear me was the task of power divine,

Supremest wisdom, and primeval love.

Before me things create were none, save things

Eternal, and eternal I endure.

|

| Gustave Dore (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Inferno 1 The Gates of Hell. |

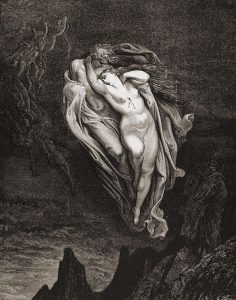

Dante’s conception of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven is an impossibly dense fusion of Classical myth and philosophy, Roman Catholic tradition, and contemporary history. His hell is divided into nine circles, each associated with a particular sin. Souls are tormented according to a concept called contrapasso, a punishment fiendishly designed to appropriately fit a particular sin. The second circle is the realm of those whose lives have been blown apart by the chaotic winds of lust.

from Canto V

I understood that to this torment sad

The carnal sinners are condemn’d, in whom

Reason by lust is sway’d. As in large troops

And multitudinous, when winter reigns,

The starlings on their wings are borne abroad;

So bears the tyrannous gust those evil souls.

On this side and on that, above, below,

It drives them: hope of rest to solace them

Is none, nor e’en of milder pang. …

so I beheld

Spirits, who came loud wailing, hurried on

By their dire doom. …

|

| Gustave Dore. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Inferno V Hurricane Tormenting the Lustful. |

Dante is instructed by Virgil’s wisdom and by interviews with sinners lost in despair. The shades of Francesca Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, two adulterers slain in a husband’s revenge, speak of the danger of lust which has doomed them to forever embrace, forever denied any satisfaction.

Entangled him by that fair form, from me

Ta’en in such cruel sort, as grieves me still:

Love, that denial takes from none belov’d,

Caught me with pleasing him so passing well,

That, as thou see’st, he yet deserts me not.”

|

| Gustave Dore. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Inferno V Paolo and Francesca. |

from Purgatorio, Canto X

Descending through the nine levels of hell, confronting sinners of greater and greater evil, Dante and Virgil pass through an aperture into Purgatory. According to Catholic tradition, baptized souls who will ultimately reach heaven must be purified by residual sin through agonizing. Purgatory is seen as a mountain rising through levels associated, as were the circles of Hell, with particular sins.

As they near the top of the mountain, Virgil takes his leave of Dante: having never been baptized, he can go no further. But Dante is consoled by the appearance of his beloved, Beatrice, who stills his tears:

“Dante, weep not, that Virgil leaves thee: nay,

Weep thou not yet: behooves thee feel the edge

Of other sword, and thou shalt weep for that.” …

I saw, …

The virgin station’d, who before appeared

Veil’d in that festive shower angelical. …

“Observe me well. I am, in sooth, I am

Beatrice. What! and hast thou deign’d at last

Approach the mountain? knewest not, O man!

Thy happiness is whole?”

|

| Gustave Dore. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Paradiso XXI Contemplating Beatrice. |

Let’s be careful here. “The virgin” here is not Mary, but rather Beatrice, whom Dante sees as a the ideal of human faithfulness. Beatrice explains that she has been watching Dante’s anguish and has planned this journey to lead him through despair and into salvation.

from Paradiso, Canto XXXIII

Having reached the summit of Purgatory, Beatrice and Dante pass through a purifying fire and begin to ascend through levels of the heavens. These are firmly located in the astronomical models of the day, leading deeper and deeper into Dante’s vision of the core spiritual reality of God.

Wondering I gaz’d; and admiration still

Was kindled, as I gazed. …

In that abyss

Of radiance, clear and lofty, seemed methought,

Three orbs of triple hue clipped in one bound:

And, from another, one reflected seemed,

As rainbow is from rainbow: and the third

seemed fire, breathed equally from both. …

Oh eternal light!

Sole in thyself that dwellest; and of thyself

Sole understood, past, present, or to come! …

Here vigor failed the towering fantasy:

But yet the will rolled onward, like a wheel

In even motion, by the Love impelled,

That moves the sun in heaven and all the stars.

|

| Gustave Dore. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Paradiso XXXIII The Empyrean. |

So Dante’s vision ends in an ecstatic, mystical union with the divine light. Paradiso ends, as do Inferno and Purgatorio, with edifying, uplifting visions of the stars.

Francesco Petrarch

|

| Andrea Castagno. (1448). Francesco Petrarca. Fresco. |

Like Dante, Francesco Petrarch was Tuscan scholar and poet who wrote verse in the vernacular of the region. Like Dante he was inspired by an idealized woman named Laura to whom he addressed many Courtly Love lyrics. Among those collected in Il Canzonieri (1327-1374) were some that pioneered a poetic form which would have immense influence over the centuries.

Petrarch. (1368). Sonnet VII, Il Canzonieri

Those eyes, ’neath which my passionate rapture rose,

The arms, hands, feet, the beauty that erewhile

Could my own soul from its own self beguile

And in a separate world of dreams enclose,

The hair’s bright tresses, full of golden glows

And the soft lightning of the angelic smile

That changed this earth to some celestial isle,

Are now but dust, poor dust, that nothing knows.

And yet I live! Myself I grieve and scorn,

Left dark without the light I loved in vain,

Adrift in tempest on a bark forlorn;

Dead is the source of all my amorous strain,

Dry is the channel of my thoughts outworn,

And my sad harp can sound but notes of pain.

The Sonnet. Surely you have heard of this Genre? Did you know that it has a form as precisely defined as the Haiku? See if you can work it out.

- Which lines rhyme with each other?

- How do the rhymes define stanzas, chunks of material that function like paragraphs?

- What themes do the stanzas develop?

- Where do the themes shift suddenly and sharply?

- How and why does the poet’s anguish intensify in the latter section of the lyric?

Does it help if we isolate these two lines? How do they clarify the poem’s dynamics and themes?

And yet I live! Myself I grieve and scorn, …

Vital Questions

Context

The context of the literary Renaissance in Italy is more or less the same as that of the artists we have been exploring. Now, writers like Dante and Petrarch were more directly engaged in scholarship per se, but again we find the fusion of Classical and Christian traditions that fueled so much Renaissance art.

Content

Apart from the allusions to Classical and Christian traditions, the content worth stressing is that of courtly love. Remember that this genre reveled in a passion that was idealized, in a sense consecrated by its celibacy. Beatrice and Laura were unapproachable, separate from the lives of the married Dante and the ex-priest Petrarch. This lifted the vision of beauty out of the realm of sexual aspiration and filled it with transcendent, spiritual signification.

Form

In some ways, The Divine Comedy is structured as a narrative, and it is certainly inspired by the Roman epic of Virgil. However, it does not really aspire to fit Aristotle’s formulation of the genre. The composition in vernacular dialect is noteworthy, but beyond the grasp of non-linguists.

Petrarch’s innovative poetic form, the sonnet, is far more accessible. We’ll be exploring it more fully in the rich tradition of English sonnets which would follow.

References

Castagno, Andrea. (1448). Francesco Petrarca [Fresco]. Legnaia, IT. Villa Carducci-Pandolfini. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14494700

Dante Alighieri. (June 6, 1290). “Upon a day, came Sorrow into me.” Trans. Rossetti, D. G. (1861). Rossetti Archive https://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/35d-1861.raw.html

Dante Alighieri. (1321). The Divine Comedy. Trans Cary, H. F. (1814). Project Gutenberg https://www.gutenberg.org/files/8800/8800-h/8800-h.htm

Dore, Gustave. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Inferno 1 The Gates of Hell [Illustration]. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15716690

Dore, Gustave. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Inferno V Hurricane Tormenting the Lustful [Illustration]. The World of Dante Gallery

Dore, Gustave. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Inferno V Paolo and Francesca [Illustration]. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13711922

Dore, Gustave. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Paradiso XXI Contemplating Beatrice [Illustration]. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13704472

Dore, Gustave. (1861-1868). Divine Comedy: Paradiso XXXIII The Empyrean [Illustration]. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13562759

Michelino, Domenico di. (1465). The Divine Comedy of Dante [Painting].] Florence, IT: Duomo. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dante_Domenico_di_Michelino_Duomo_Florence.jpg

Petrarch, F. (1368). Sonnet VII T. W. Higginson [Trans.]. In T. W. Higginson (Ed.) Fifteen Sonnets of Petrarch. New York: Houghton Mifflin & Company, 1903. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/50307/50307-h/50307-h.htm.

Petrarch. (c. 1420-1430). Il Canzoniere. Folio #: fol. 001r. [Manuscript Illustration]. Oxford, UK: Bodleian Library. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/BODLEIAN_10310369599.

Picone, M. (2002). Petrarch, Francesco. In P. Hainsworth & D. Robey (Ed.s), The Oxford Companion to Italian Literature. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198183327.001.0001/acref-9780198183327-e-2435.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. (1864-1870). Beata Beatrix [Painting]. London, UK: Tate Britain AN 1279 https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rossetti-beata-beatrix-n01279

Signorelli, Luca. (c 1500). Dante Reading [Painting]. Orvieto, IT: Duomo di Orvieto. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14500355

a Medieval poetic tradition deriving from Arab verse and 12th Century French troubadours in which a poetic voice proclaims a spiritually exalted, chaste love for an unattainable beloved, often the wife of the lover’s liege lord (feu-dal master). A conception of transcendent sexual love that remains influential in modern culture and its arts.

a 14-line lyric poem that explores a theme in stanzas with a thematic turn either between lines 8 and 9 (Petrarchan/Italian Sonnet) or between lines 12 and 13 (Shakespearian/English Sonnet).

a particular type of composition marked by expected, conventional features: e.g. Japanese haiku, Chinese landscape painting, Renaissance sonnet

a Japanese poetical genre in which 17 syllables deftly evoke a poignant, often seasonal nature scene that shifts with a cutting word into a thematic reflection on life

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

a telling of a story using some medium: prose, poetry, cinema, painting, etc.

an extended, mythic narrative celebrating the trials and triumphs of heroes exemplifying a culture’s treasured values and orienting its origins