7.9 The Renaissance Model

OK. You’ve heard the word Renaissance, and you’ve heard of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt. But the Renaissance as a whole? The Baroque era? That’s all really something, eh? I wonder if your head is buzzing. Can you keep it all straight? Do you need to? Well, ask yourself a question:

What IS painting?

I mean, what makes it up? What is it supposed to do? How do we know if it is any good? If you walk around in a museum, what do you look for?

Your answers, of course, are your own. Still, many, many people share a fundamental set of assumptions about paintings that descends from the materials we have explored in this chapter. Let’s review what we might call a Renaissance model of painting. As we do so, ask yourself if, possibly despite having never thought about it, you have just assumed that this is what painting is.

A Window on the World

Two master metaphors are often used to characterize the Renaissance conception of a painting. We can think of a painting as a proscenium arch framing the stage for an audience in a theater. Or we can think of it as a window. Both metaphors share a framework opening onto a visual scene extending deeply into space.

As we have seen, before the Renaissance era, a painting was rarely seen as a composition of visual space with the illusion of depth. By the Baroque era, European artists assumed that they had to create Virtual Space with convincing depth and Perspective. Within that space, visual subjects should be composed with precisely modeled and scaled Mimetic detail. All this, it came to be assumed, was what a “good” artist did.

The notion of a painting as a window on the world, emulating our vision of a moment in time and space, was so strong that Renaissance painters placed windows in the walls behind subjects of portraits. We see this Convention, the Veduta, in Leonardo’s Madonna of the Creation. Behind the mother are windows opening onto a landscape with distant mountains. Look for them and you will see the Veduta in hundreds of Renaissance compositions.

|

|

|

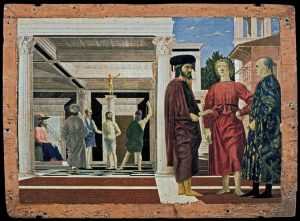

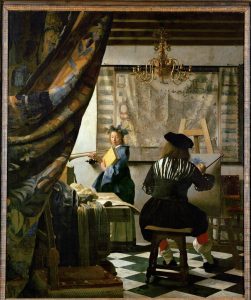

| Madonna of the Carnation. ( 1478). Oil on canvas. | Piero della Francesca. (1470). Flagellation of Christ. Oil, tempera, panel. | Jan Vermeer. The Artist’s Studio. (1665). Oil on Canvas. |

Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ dramatizes a key moment from the gospels. But the work’s focus is on Classical style and technique. Christ’s suffering is recessed and eclipsed in our awareness by sumptuous classical architecture and the elegant Greek column to which he is bound. Prominent Linear Perspective breaks a moment of vision down into zones of depth: foreground, middle distance, deep distance—precisely the concerns that challenge photographers today. The right half of the image is dominated by three contemporary, enigmatic men standing in the foreground, apparently disinterested in the drama.[1]

In his The Artist’s Studio, Vermeer playfully takes things much further. A theatrical curtain defines the picture pane, a framework for the canvas through which we see the scene of the studio. This firm point of view directs our eyes to a pair of virtual acts of perception. The model gazes downward at fabrics on a table. The artist gazes at the model. Simultaneously, we see the hand and brush bringing into being a doubled representation of the model on a virtual canvas, a secondary window frame. Finally, a map covers the back wall, yet another window on the world.[2]

[1] The identity and significance of the three men has been a topic of scholarly contention for a long time

[2] The map has political and historical significance. It defiantly represents the Protestant provinces of the Netherlands during a time of conflict and war with the Catholic Holy Roman Empire.

The Primacy of the Illusion

Classical Greek artists concerned themselves with the structure and function of vision in the world. They sought to compose accurate representations of the human body captured in moments of time. Renaissance artists recaptured this commitment to Mimesis. They tackled religious subjects and portraits and innovated new contents such as landscapes and domestic scenes. But whatever subjects they chose, they felt compelled to achieve mimetic authenticity.

Following in the tradition of the ancient Greek painter Zeuxis who wanted to paint accurately enough to fool birds, the values of the Renaissance craft of painting were deeply committed to the task of achieving the illusion of beholding “the real thing.” While they face different compositional tasks than linear perspective, Renaissance sculptors shared that mimetic commitment. The grip of Illusionism on people’s expectations of art would last a long time.

How about you? Do you value illusions of seeing through a window above all else?

References

Leonardo da Vinci (circa 1478). Madonna of the Carnation [Painting]. Munich: Alte Pinakothek. https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/en/artwork/Y0GR916LRX

Francesca, Piero della. (c.1455-60). Flagellation of Christ [Painting]. Urbino, Italy: Palazzo Ducale. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/piero-della-francesca/the-flagellation-of-christ-1450-1

Vermeer, J. (c 1668) The Art of Painting [Painting]. Vienna, Austria: Kunsthistorisches Museum. https://www.khm.at/en/artworks/the-art-of-painting-2574-1

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate im-ages and actions in time and space

the 17th Century artistic tradition that followed the Renaissance, characterized by gritty social realism, dramatic action, depth of characterization, closed compositions, and intense contrasts between light and shadow. More broadly, any art emulating the values of the Baroque

in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

in visual art, the illusion of 3-dimensional forms and spaces in 2-dimensional compositions by aligning and scaling forms to suggest depth and distance.

art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

common in the Italian Renaissance, an interior portrait scene with a window in the back wall opening onto a landscape in the distance

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

a representational technique in visual art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”