7.8 The Baroque

So how do you follow the era of Leonardo and Michaelangelo? Well, you draw on Renaissance skills and techniques, and then you take them on to another level. To get a feel for the so-called Baroque era of art, compare these paintings. What do you see?

|

|

| Andrea del Sarto, A. (1513). The Annunciation. Oil on canvas. | Artemisia Gentileschi. (1619). Judith and her Maidservant. Oil on canvas. |

Let’s apply what we have been learning about spatial composition to the del Sarto. The figures in the foreground are the primary visual subjects who invoke the vast Signification of the Mother of God. But the composition opens out into an architectural middle distance and the Negative Space of the open skies. The composition reaches out into a wider world.

As does del Sarto, Gentileschi focuses on few visual subjects. But what else do we see? Nothing. The composition closes in on dramatically lit Judith and her maidservant who are engulfed in an apparent world of darkness. That is, the Baroque. Well, a certain sort of Baroque.

The Spectacular Baroque

The word baroque can designate “art of any time or place that shows the qualities of vigorous movement and emotional intensity.” In the 17th Century, aristocratic and royal powers in Europe achieved stunning levels of wealth and prestige. The art that they commissioned overflows with a staggering surfeit of spectacle and luxury. The techniques developed during the Renaissance were pushed to the extreme to proclaim to all the glory of God, the Church of Rome, and the authority of nobility and monarchs.

In the ceiling of the Barberini Palace, Pietro da Cortona, composed a vast Allegory celebrating the triumphs of the Papacy in its ongoing campaign to stamp out the Protestant Reformation. The composition centers on a personification of Divine Providence with individual battles between virtues and vices radiating outward. Throughout, it teems with symbolic references to the glories and virtues of the Barberini family.

|

|

| Pietro da Cortona. (1639). The Triumph of Divine Providence and the Fulfilment of its Purposes under Pope Urban VIII. Ceiling Fresco. | Charles Le Brun. (1686). Paintings in the Hall of Mirrors. |

Perhaps the ultimate expression of the Baroque spirit was the overwhelming opulence of the Palace of Versailles, built beginning in 1661 by Louis XIV of France, a monarch so wealthy, so besotted with royal power that he named himself The Sun King, the center around which all life flowed. Versailles is a massive architectural structure surrounded by spectacular formal gardens. The halls drip with luxury, gilt fixtures, neo-classical sculptures, and sumptuous paintings, many composed or overseen by the Baroque painter Charles Le Brun.

Each year, thousands of visitors tour the palace, testifying to the on-going appeal of overwhelming spectacle. And yet, it can be hard to actually engage with it all. Ironically, the specific works of Baroque art most celebrated today embraced a far narrower scope of Composition.

The Moody, Constricted Baroque

Who are the masters of the Baroque era celebrated today with the greatest enthusiasm? Caravaggio. Vermeer. Rembrandt. Gentileschi. These Italian and Dutch painters, developed Renaissance innovations to achieve intense effects: closed composition, internal light and shadow, naturalistic representation, and oil paint technique.

Vermeer: Consecration of Light

In Reformed Holland, the vigorous suppression of Christian Iconography under suspicion of idolatry led to a natural focus on domesticity. Wealthy Portrait subjects like the Arnolfinis showed off their affluence by standing proudly within richly furnished homes. This led to a painterly interest in the home and its inhabitants, including humble servants.

In the work of the Dutch painter Jan Vermeer we see the Genre Painting, a tradition that depicted domestic scenes and elements of daily life. We find little drama or thematic signification in his Woman Reading a Letter. What we do find is a graciously composed interplay of harmonious colors and forms. True to Dutch tradition, Vermeer bathes the scene in sunlight, a quiet, domestic form of consecration.

|

|

| Woman reading a letter at window. (ca. 1659). Oil on canvas. | The Kitchen Maid. (1660). Oil on canvas. |

The subtle interplay of light and shadow is even richer in The Kitchen Maid, a composition long erroneously described as The Milkmaid. (Milkmaids work in dairies not kitchens.) The socially insignificant figure of a servant is consecrated by warm light. Textures of dress, food, and pouring milk are exquisitely rendered and enriched by vibrant, ultramarine blues.

Viewers and artists have long admired the uncanny Mimetic accuracy of Vermeer’s scenes. Although little is known of Vermeer’s life and career, scholars have of late speculated that he used a visual device to achieve results of almost photographic precision.

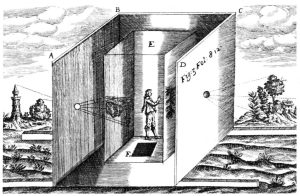

The camera obscura [Latin for dark chamber] had been used since the early Renaissance to facilitate accurate drawing. A Camera Obscura could project an image on a wall or the back of a box. As Albrecht Dürer used drawing machines for precision, so Vermeer apparently used the camera obscura to achieve an astonishing level of naturalistic illusion.

|

| Athanasius Kircher. (1671). Diagram of a Camera Obscura |

Vermeer’s famous Girl with a Pear Earring, however, moves away from the Genre Painting paradigm. While meticulously delineating the play of light, this portrait contracts the field of the composition and surrounds its subject with black negative space. Vermeer was drawing on the heritage of an Italian rogue named Caravaggio.

|

| Girl with a Pearl Earring. (1665). Oil on canvas. |

Caravaggio, the Pope’s Bad Boy

Italian and Dutch painters of the Baroque era were profoundly divided by the religious conflicts of the 17th Century. Lutheran and Reformed churches were opposed by the Counter-Reformation which strove to pull rebellious believers back into the Roman fold. Dutch artists painted domestic scenes; Italians like Caravaggio were commissioned to paint biblical scenes for display in Churches.

Caravaggio willingly took up traditional Christian themes. But he laid aside Renaissance masters’ idealized pursuit of beauty to achieve a gritty realism. His biblical scenes are set in the mean streets of Rome. St. Matthew, the disciple is called away from his tax revenues in a seedy Roman tavern.

Take a moment to consider the composition of this work. The scene is constricted by the tavern’s interior. It is dramatically lit by shafts of light which align with the Eyelines and pointing arms of Jesus and his follower (Peter? John?) and again with Matthew’s bewildered finger: “Who, me?” Notice the diverse responses of faces, some lit and some left in darkness.

|

|

| The Calling of Saint Matthew. (1599-1600). Oil on canvas. | Beheading of John the Baptist. (1608). Oil on canvas. |

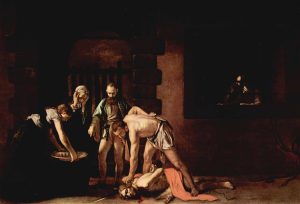

Caravaggio’s Beheading of John the Baptist locates the action in a back alley, witnessed by prisoners behind bars and lit with the skill of a stage designer. Again, the narrative drama of the scene is intensified by dramatically contrasted light and shadow. Caravaggio would lay in a dark background on the canvas, then build up figures and light to spotlight characters as if on a stage.

Intense contrast of light and shadow came to be called Chiaroscuro, Italian for light-dark. Chiaroscuro can be seen in Leonardo (e.g. Virgin of the Rocks) and in Rembrandt (see below). Centuries later, it would play a powerful role in black and white cinematography: German Expressionism in the silent era and what French critics termed Film Noir, i.e. dark cinema, marked by dark themes and dramatically lit visuals.

Chiaroscuro became Caravaggio’s signature technique. In Supper at Emmaus, the resurrected Christ breaks bread with the weathered faces of disciples and serving women (Luke 24.13-49). Again, dramatic lighting enhances drama and psychological depth. But notice how that black background focuses the scene. This closed composition presents five figures … and nothing else. The foreshortening and precise modeling give depth to the foreground and the table suggests linear perspective, but no middle or deep distance open up.

|

| Supper at Emmaus. (c 1606). Oil on canvas. |

Caravaggio’s techniques enhance the drama of his scenes. But his life experiences lend him insights into the human heart that is rare in religious painting. His own struggles with wickedness and redemption equip him to fearlessly explores the flashpoint of sin and grace. His Incredulity of Saint Thomas profoundly humanizes the struggles of the disciple who doubted Jesus’ resurrection.

A week later his disciples were in the house again, and Thomas was with them. … Jesus came and stood among them and … said to Thomas, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.” Thomas said to him, “My Lord and my God!” (John 20.24–29). Caravaggio’s Thomas is all too human, probing Christ’s living tissues beneath a furrowed brow that intensely seeks truth. Doubt, faith’s other side, engenders an intimate encounter with the incarnate Lord.

|

|

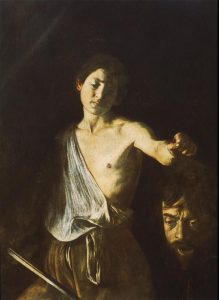

| The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. (ca. 1601-1602). Oil on canvas. | David & Head of Goliath. (1610). Oil on canvas. |

Caravaggio’s life was steeped in human fallibility. After killing a man in a street brawl, Caravaggio was banished from Rome. For years he beseeched the Pope for pardon. As an act of penance, he painted his own face on the head of Goliath held aloft by David. Caravaggio knew how to invest himself in his work!

Gentileschi’s Heroic Women

Artemisia Gentileschi learned two lessons from her painter father’s mentor, Caravaggio: Chiaroscuro and gritty realism. Gentileschi also learned and triumphed over the lessons of a gifted woman striving to thrive in a male-dominated world. She became known for painting women in well-known biblical and mythic scenes but conferring on them a quality of heroic strength missing from male painter’s versions.

Let’s compare two versions of Judith, a Jewish princess, saving her people by beheading the Babylonian general Holofernes in his drunken slumber, (The Book of Judith[1]). How would you compare the characters of these two differently conceived Judiths?

[1] The Book of Judith was included in the Vulgate, St. Jerome’s Latin translation of Hebrew scriptures and the basis for Roman Catholic scripture ever since. In the 17th Century, Protestant translations of the Bible excluded Judith and other so-called “apocryphal” books from the Protestant biblical canon.

|

|

|

| Caravaggio. (1598), Judith Beheading Holofernes (1620). Oil on canvas. | Gentileschi. (1620). Judith Beheading Holofernes. Oil on canvas. | Judith and her Maidservant. (1625). Oil on canvas. |

Caravaggio’s Judith stands back from her gruesome deed, perplexed and horrified. Gentileschi’s Judith is a woman of power untroubled by doubt. She wields her sword with a warrior’s focus. In a pair of supporting compositions, Judith and her servant cooly navigate the threats of the enemy, Judith’s sword resting nonchalantly over a potent shoulder. Artemesia’s Judith is a woman, not a girl displayed for the male gaze.

Gentileschi throve within a tradition of feminism emerging among humanist scholars and female counter-Reformation leaders (Garrard, 1989, 143ff). She boldly inhabited roles monopolized by men: painter, entrepreneur, head of family. In letters to a patron, Don Antonio Ruffo, Artemisia confronts the challenges she faced (Trans. Garrard, 1989, Appendix A):

“You think me pitiful, because a woman’s name raises doubts until her work is seen” (Letter 16).

“You will find the spirit of Caesar in this soul of a woman” (Letter 24).

“If I were a man, I can’t imagine it would have turned out this way”[2] (Letter 25).

[2] Turned out this way: the reference is to a bishop who commissioned a painting, asked for preliminary drawings, then hired someone cheaper to complete the work.

Determined “to compete with topflight male artists” (Garrad, 1989, 6), Gentileschi incorporated avant garde styles and in turn influenced traditional art communities: she is widely recognized for having brought Caravaggio’s techniques to Florence. She mastered prestigious religious and mythic genres while reconfiguring them to reflect a woman’s point of view, what Garrad describes as an “inspired transformation of formal prototypes,” “a special mixture of masculine and feminine elements” (7). In contrast to male painters’ often erotic portrayals of the feminine ideal, her images embraced “ average, imperfect women” with realistic depictions of what are harshly thought of as physical flaws (Barker, 2022, 93, 123).

|

| Artemisia Gentilesch. (1639). Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting Oil on canvas. |

Figures of women were traditionally painted to personify abstract qualities, virtues, vices, or professions. Artemisia’s allegory of Painting—in Italian, Pittura—portrays herself at work, brush hand reaching upward for inspiration, palette hand resting firmly on the horizontal stability of the world (Garrard, 1989, 367). Her gaze peers at and into her subject: her own mirrored image, portal to the inwardness from which her art flows. Perhaps most remarkably, the canvas on which Pittura paints is presented as a negative space rich with the textures of the actual painting’s canvas, a celebration of medium and inspiration.

The Eye and Brush of Rembrandt

In Rembrandt van Rijn, we see a powerful culmination of the developments emerging from the Renaissance. The brushwork. The Chiaroscuro. The Linear Perspective and Foreshortening. And the dramatic intensity that emerged during the Baroque era. There is much to say, for example, about the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, and we will return to it. The scene dramatizes the incident remembered in Matthew 8, Mark 4, and Luke 8 in which Jesus calms a storm terrifying His disciples. Notice how Rembrandt uses zones of light to bring salvation to the men trapped in the darkness of the sea as a destructive element.

|

| Storm on Sea of Galilee. (1633). Oil on canvas |

Rembrandt’s pitiless eye for the truth of a scene can be seen in his many self-portraits. He returns to his own face again and again, not out of egomania, but in a relentless examination of the truth of his countenance, flaws and all, and the depredations of age.

|

|

| Youthful Self-Portrait. (1629). Oil on panel. | Self-Portrait with Beret. (1639). Oil on panel. |

|

|

| Small self-Portrait. (1650s). Oil on panel. | Self-portrait with palette and brushes. (1661). Oil on canvas. |

In Rembrandt, we can see the emergence of texture as a primary Formal feature. The conventional use of oil paint was to achieve a smooth, glassy surface into which paint and brushstrokes largely disappeared. Rembrandt, however, boldly enhanced the Textures of his media. With heavy strokes of a laden brush, he built up layers of pigment that appeal to our touch. At the same time, he would inscribe details with a feathery touch of the brush.

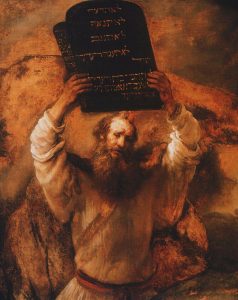

|

| Moses with the Tablets of Law. (1659). Oil on canvas. |

Rembrandt’s masterpiece, “so discolored with dirty varnish that it looked like a night scene,” was long mislabeled The Night Watch. The painting, over 12 by 14 feet, “showed remarkable originality in making a pictorial drama out of an insignificant event,” the mustering of a company of militia. The great canvas repays long study: “[subordinating] individual portraits to the demands of the composition,” Rembrandt injects an overflowing barrel of life into the scene, dozens of figures, prominent and obscure, caught in individual moments of drama.

|

| The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch,. (The Nightwatch). (1642). Oil on canvas. |

Vital Questions

Context

One cannot approach the works of the Northern and Southern Baroque without a sense of the religious conflicts that would torment the 17th Century. The English Civil Wars, the Thirty Years’ War, the slaughter of Protestant Huguenots in France—these conflicts would kill hundreds of thousands of people. Far less destructive but ideologically crucial were the conflicts played out in print and on canvases by theologians, states people, and artists. The spectacular dimensions of Baroque art were driven, especially in Catholic Europe, by a reactionary impulse to reassert the authority and glory of l’ancien régime, the traditional privileges of church and aristocracy.

The Baroque of Caravaggio, Gentileschi, Vermeer, and Rembrandt reflects an introspective impulse shared by the Catholic South and the Protestant North. These masters turned inward, embracing the richness of the soul working through the challenges of dramatic moments and of everyday life.

Content

The Italian Baroque pushed the drama of Christian art to its limits. Caravaggio and Gentileschi achieved unprecedented levels of psychological depth in their conceptions of biblical characters as deeply feeling and thinking human beings.

Meanwhile the Dutch Baroque embraced the everyday world with enthusiastic eyes. In a reduced market for religious works, domestic scenes and land and seascapes began to earn legitimacy and respect that would culminate in later centuries.

Form

Many Baroque compositions shared a flair for dramatic formal intensity. Compositions were enclosed, light and shadow contrasted, and the textured media of the painter began to proclaim itself. The formal innovations of later centuries were just beginning to suggest themselves.

References

Barker, S. (2022). Artemisia Gentileschi. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

Caravaggio, M. (1608). Beheading of John the Baptist [Painting]. Valetta, Malta: St. John’s Co-Cathedral. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13583843

Caravaggio, M. (1599-1600). The Calling of Saint Matthew [Painting]. Rome, IT: San Luigi dei Francesi. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14490796

Caravaggio, M. (1609-1610). David with the Head of Goliath [Painting]. Rome: Galleria Borghese. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14482831

Caravaggio, M. (c 1601-1602). The Incredulity of Saint Thomas [Painting]. Potsdam, Germany: The New Palace. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18114019

Caravaggio, M. (c 1598). Judith Beheading Holofernes [Painting]. Rome, IT: Galleria nazionale d’arte antica. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14496013

Caravaggio, M. (1609-1610). Supper at Emmaus [Painting]. Milan, IT: Pinacoteca di Brera. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14502353

Garrad, M. D. (1989). Artemisia Gentileschi: the Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Gentileschi, A. (1620). Judith Beheading Holofernes [Painting]. Florence, IT: Palazzo Pitti. Jstor. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13603240

Gentileschi, A. (1620). Judith Beheading Holofernes [Painting]. Florence, IT: Uffizi Gallery. Inv. 1890 n. 1567 https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/judith-beheading-holofernes

Gentileschi, A. (169). Judith and her Maidservant [Painting]. Florence, IT: Galleria dell’Accademia. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14503274

Gentileschi, A. (1639). Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting [Painting]. London, UK: Buckingham Palace Royal Collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/artemisia-gentileschi/self-portrait-as-the-allegory-of-painting-1639

Jan Vermeer [Article]. (2004). In The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Chilvers, I. (Ed.). https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-3632

Kircher, Athanasius. (1671). Camera obscura [Diagram]. Ars Magna. Amsterdam. Oxford, UK: Oxford Science Archive.Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.9196304

Portable Camera Obscura [Diagram]. (c 1850). Rochester NY: George Eastman House. JStor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13877478

Langdon, A. (2001). Caravaggio. In Brigstocke, H (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press,. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-464.

Rembrandt. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-2923.

Rembrandt. (1642). The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch, (The Night Watch). [Painting]. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15665282

Rembrandt. (1659). Moses with the Tablets of Law [Painting]. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Reichsmuseum. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13558726

Rembrandt. (1639). Self-portrait with Beret. Florence, IT: Uffizi Gallery. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14480400

Rembrandt. (1661). Self-portrait with palette and brushes. London, UK: Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13601509 https://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13601509

Rembrandt. (1650s). Small Self-Portrait [Painting]. Vienna, AU: Kunsthistorisches Museum.. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18111293

Rembrandt. (1633). Storm on Sea of Galilee [Painting]. Boston, MA: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Stolen—whereabouts unknown. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13579121

Rembrandt. (1629). Youthful Self-Portrait [Painting]. Munich, Germany: Alte Pinakotek. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18116983

Vermeer, J. (c.1665). Girl with a Pearl Earring [Painting]. The Hague: Mauritshuis. ID 670. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13594649

Vermeer, J. (ca. 1660). The Kitchen Maid (Milkmaid) [Painting]. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15654414

Vermeer, J. (ca. 1659). Woman reading a letter at the open window [Painting]. Dresden, Germany: GemΣldegalerie. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18116888

Vermeer, Jan. (1665-1666). The Painter and his Model as Klio. Oil on canvas. Vienna, Austria: Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18120937

Vermeer, Johannes [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-3632.

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

a sector of a visual composition that seems empty, devoid of clearly defined and weighted visual subjects

the 17th Century artistic tradition that followed the Renaissance, characterized by gritty social realism, dramatic action, depth of characterization, closed compositions, and intense contrasts between light and shadow. More broadly, any art emulating the values of the Baroque

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate im-ages and actions in time and space

representation of an abstract concept as a symbol or person, often a personification of the idea

a trope which speaks of an abstract concept as if it is a person. E.g. “Because I could not stop for Death—He kindly stopped for me” (Emily Dickinson)

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc

A conventional system of significations that associate details of appearance with particular religious figures

in visual art, a composition that represents a human subject as an individual, meticulously capturing physical or psychological likenesses

paintings that depict domestic scenes and elements of daily life, associated with 17th-century Dutch artists who were commissioned by house-proud patrons. Disdained by 18th and 19th Century academic artists as a lesser form.

in visual art, the illusion of surface feel either of A) the represented object (e.g. textures of clothing) or B) of the artifact’s media (e.g. canvas weave, brushstrokes, daubs of paint)

art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

a light capturing device which projects the reverse of an image through a pinhole on a rear surface. Since at least the 17th Century, artists have used camera obscuras to create images with precise accuracy.

an implied line defined by the direction stretching from the gaze of a figure in the scene

in Italian, “light/dark,” a style of art that powerfully contrasts light and dark effects. Associated with Baroque painting, but common in the art of the early 20th Century: e.g. German expressionism and film noir cinema

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

an illusion of depth created by contrasting the sizes of objects on the basis of how near or far they are from the eye of the viewer. E.g. a human figure in the foreground will be larger than a tall building in the distance.

in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any subject or signification: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement