7.4 The Emergence of Space

Vasari’s 2nd stage of the Renaissance era begins with a fusion of art and mathematics that innovates a dimension of painting that had previously been rarely developed.

Virtual Space: in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

Picture Pane: the virtual window glass through which the 2-dimensional surface of a painting’s Medium—fresco, canvas, panel—”looks out” into a projected space

The sense of these terms may come clear in a comparison of three paintings.

|

|

|

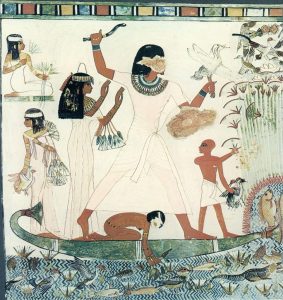

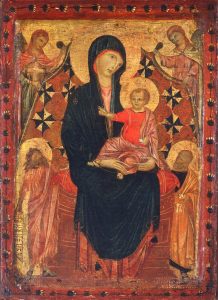

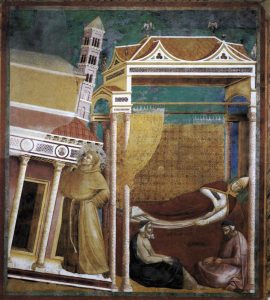

| Hunting scene. (c 1415 B.C.). Tomb of Menna | Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. Tempera. | Giotto di Bondone. (c 1290). Dream of Innocent III. Fresco. |

The Hunting Scene and the Cimabue make minimal use of Virtual Space. The first composes disjointed sections of an actual scene with little regard for their arrangement in visual reality. The Cimabue arranges objects and figures with marginal sense of depth. Both present a Picture Pane with little depth.

By contrast, Giotto composes the illusion of an actual visual scene with what photographers call Depth of Field. The figures align in the foreground, buildings loom behind them, and a landscape stretches away into the deep distance. As a narrator projects figures, objects, and events into an imaginary story world, Giotto projects a Virtual Space receding into illusory depth.

This innovative projection into virtual space formed a core formal dimension of the art of the Renaissance. Giotto’s pioneering experiments are part of his legacy. And yet, as we look at it, don’t we feel that the results are somehow … well, off?

Vasari’s 2nd Renaissance Period: Perspective

The 2nd stage of Vasari’s Renaissance timeline refers to a transitional period in which painters embraced the challenge of projecting virtual space in a 2-dimensional composition and doing so in an authentic fashion matching the way vision actually works.

The Art of Perspective

The art of depicting solid objects on a two-dimensional or shallow surface so as to give the right impression of their height, width, depth, and position in relation to each other. Only certain cultures have embraced perspective, for example, … ancient Egyptians took no account of spatial recession.

Mathematically-based perspective, ordered round a central vanishing point, was … invented by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446), described by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) in his treatise Della Pittura, and is often referred to as Linear Perspective. … The stage-like organization of pictorial space, in which the composition of a picture is conceived as though viewed through a window, remained a central feature of much western art until the later part of the 19th century (Perspective, 2010).

This is the point at which the Renaissance fully embraces the legacies of Classical learning. Brunelleschi, a major architect who designed the Duomo (Cathedral) of Florence, worked out the geometrical formulae which correspond to the function of human vision.

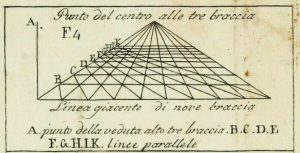

|

|

| Leone Battista Alberti. (1472). Diagram of perspective lines | Detail: Vanishing Point |

Page 178 of Alberti’s Della Pittura (1472) provides diagrams that capture the mathematically precise guidelines followed by Renaissance painters in achieving convincing effects of Linear Perspective. Angled lines converge in a distant Vanishing Point “usually located on the horizon, towards which receding lines such as railway tracks appear to converge when depicted or viewed in linear perspective” (Vanishing Point, 2015).

Masaccio: Pioneer of Perspective

To see the Renaissance emerge before your eyes, visit the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. Look for a niche reaching back into the wall on the left. But wait! The apparent niche is actually a Fresco on a flat wall: Masaccio’s The Holy Trinity, a fresco depicting the three persons of the Christian God: Father, Son, and Spirit. Virtual architectural lines converge in angles that project a vanishing point. Brunelleschi’s formulae guide Masaccio in achieving a precision that perfectly achieves the illusion of depth

|

|

| Masaccio. (1427). The Holy Trinity. (1427). Fresco | Masaccio. (c 1427). The Tribute Money. Fresco |

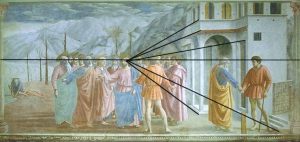

A few blocks over in Florence, Masaccio’s The Tribute Money joins other frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine. This Fresco dramatizes the story of Jesus paying his tax by sending Peter to look for a coin in the mouth of a fish (Matthew 17.24-27). This composition is a bit tricky. It fuses three moments of time in the story: Jesus directing Peter to find coins for tax payment (center), Peter finding the coins in a fish’s mouth (left), and Peter paying the tax collector (right). These separate narrative moments are unified in a visual field unified by perspectival lines.

|

| The Tribute Money with indicated perspectival lines |

Perspective and Foreshortening

The illusion of spatial depth is achieved with several techniques. One figure overlapping another clearly indicates spatial arrangement. So does scale—scale, that is, when composed with an eye to visual illusion. We have seen earlier traditions in which human figures are scaled small or large according to social status. But consider the del Sarto below.

|

|

| Andrea del Sarto. (1513). The Annunciation. Oil on panel. | Andrea Mantegna. (1490). Dead Christ. Tempera on canvas |

In del Sarto’s composition, the figures in the foreground are much larger than the onlookers on the balcony of a building which would be taller if it were closer in the composition’s field.

Foreshortening combines with Linear Perspective to produce the illusion of depth of field. It also plays a key role in achieving precise imitation of the appearance of a visual subject. Mantegna’s innovative version of a Pieta establishes a precisely considered point of view for us, the viewers. We stand at Jesus’ feet and the body stretches back, the size of its anatomical features receding with perfect foreshortening.

Maturing Perspective

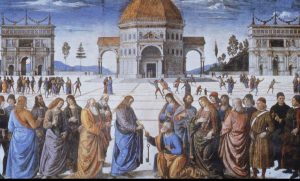

As the 15th Century progressed, artists in Italy developed their techniques for precisely rendering authentic Perspective. With some artists, it became a kind of mania, leading to disconnected themes, especially with biblical compositions. Perugino commemorates Christ giving the keys of heaven to Peter. But the devotional impact of the scene is overshadowed by the sheer exuberance of his depiction of architectural spaces projecting linear perspective.

|

|

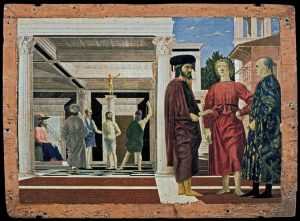

| Pietro Perugino. (1482). Christ Conferring the Keys to St. Peter. Fresco. | Piero della Francesca. (c.1455-60). Flagellation of Christ. Oil and tempera on panel. |

Piero’s famous depiction of the flagellation of Christ prior to His Crucifixion sacrifices devotional pathos to perfect perspectival composition. The perspectival lines of the architecture and the foreshortened scale of the figures are mathematically precise. But Christ and Pilate are too distant to have much impact and the three unknown figures in the foreground dominate our vision without signifying a great deal.

Vital Questions

Context

In Vasari’s 2nd stage of the Renaissance, artists in one context embraced, appropriated, and developed the vision and techniques of a context that had been lost for centuries. In turn they established a model of visual representation that would dominate the artistic tradition into our own day. If you feel more comfortable viewing a del Sarto or Perugino than you do a Cimabue or Giotto, it is because that model has been deeply woven into our conventional values and expectations. As we will see, painters would eventually challenge these conventions, but the very potency of their rebellion draws on the power of Renaissance conviction.

Content

Renaissance painters pioneered an exploration of virtual space and depth of field in two dimensional compositions. They furthermore situated their scenes in realistic settings filled with buildings, natural features, vegetation, and passersby. Their vision embraced a kind of photographic composition of a real world moment in time and space. Their handling of those materials invited viewers to reflect on the anatomy of visual experience.

At the same time, they remained faithful to their Christian context. The vast majority of their compositions were biblical or iconic. They painted Mary, Jesus, biblical scenes and saints. The more we know of the Christian background, the more we can understand of the signification of their visual subjects. This dual nature lies at the core of Christian Humanism.

Form

The formulae and techniques of linear perspective and foreshortening enabled Renaissance painters to reinvigorate the Classical value of Mimesis: precise, naturalistic modeling of subjects that mimics “the real thing.” Painters drew on mathematical formulas and used drawing devices to perfectly capture the subject. They labored to compose authentically detailed figures and objects in alignments that conformed to the laws of perspective. The influence of these techniques would live long after they were gone.

References

Alberti, Leone Battista. (1472). Diagram of perspective lines and vanishing point. In Della Pittura. Milan, Italy: Società tipografica de’Classici italiani. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/dellapitturaedel00albe/page/n4.

Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art. Accession Number 1952.5.60. https://www.nga.gov/artworks/41675-madonna-and-child-saint-john-baptist-saint-peter-and-two-angels

Francesca, Piero della. (c.1455-60). Flagellation of Christ [Painting]. Urbino, Italy: Palazzo Ducale. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/piero-della-francesca/the-flagellation-of-christ-1450-1

Giotto di Bondone. (c 1290). Dream of Innocent III. Panel 6. Legend of St. Francis: [Painting]. Legend of St. Francis. Assisi, IT: Basilica di S. Francesco. Web Gallery of Art https://www.wga.hu/html_m/g/giotto/assisi/upper/legend/franc06.html

Hunting scene [Painting]. (c 1415 B.C.). Thebes, E.G.: Tomb of Menna. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 30.4.48. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548437

Linear perspective. (2009). [Article] In A. M. Colman (Ed.) A Dictionary of Psychology. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100107214.

Mantegna, A. (circa 1490). Dead Christ [Painting]. Milan, Italy: Pinacoteca di Brera. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/andrea-mantegna/the-dead-christ-1478

Masaccio. (1427). The Holy Trinity [Fresco]. Florence, Italy: S. Maria Novella. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/masaccio/the-trinity-1428

Masaccio. (ca. 1427). The Tribute Money [Fresco]. Florence, Italy: Brancacci Chapel. Santa Maria del Carmine. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/masaccio/the-tribute-money-1425

Perugino, Pietro. (1482). Christ Conferring the Keys to St. Peter [Painting]. Rome (Vatican: Sistine Chapel). https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/cappella-sistina/parete-nord/storie-di-cristo/consegna-delle-chiavi.html Fresco

Perspective. (2010). [Article]. In M. Clarke & D. Clarke (Ed.s). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-1292.

del Sarto, A. (1513). The Annunciation. [Painting]. Florence, Italy: Palazzo Pitti. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/andrea-del-sarto/the-annunciation-1513

Vanishing point. (2015). [Article]. Colman, A. [Ed.] A Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199657681.001.0001/acref-9780199657681-e-8726.

the virtual window glass through which the 2-dimensional surface of a painting’s Medium—fresco, canvas, panel—"looks out” into a projected space

in photography, the technique of adjusting the lenses to achieve clear focus on the foreground, the middle distance, the deep distance, or all distances at once (Infinity)

in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

in visual art, the illusion of 3-dimensional forms and spaces in 2-dimensional compositions by aligning and scaling forms to suggest depth and distance.

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

a painting medium in which pigments are applied to wet, freshly applied plaster, which acts as a binding medium as it dries

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate im-ages and actions in time and space

a function of visual art which seeks to emulate a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

an aspect of art which is expected and understood by the audience in a particular tradition

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

A) a 14th Century shift in European culture from a narrow, exclusive focus on scripture and Church interests to a broader interest in cultural traditions, especially those of classical Egypt, Greece and Persia. B) a perspective that values and focuses on the capacities of human beings for knowledge, wisdom, and creativity.

an illusion of depth created by contrasting the sizes of objects on the basis of how near or far they are from the eye of the viewer. E.g. a human figure in the foreground will be larger than a tall building in the distance.

a representational technique in visual art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”