7.5 Botticelli’s Dual Vision

Sandro Botticelli was born in 1445 in the wealthy city of Florence. He quickly found patronage at the hands of the powerful Medici family. In his luminous work we behold the dual vision of Christian Humanism.

Ecclesiastical Iconography

We have seen that a response to Egyptian or Hindu art requires some knowledge of the religious signification of its features. In the same way, a viewer of European Catholic art must know something of its Conventions and Iconography:

Iconography: a system of significations that are conventionally associated with designated symbols that link figures with detailed attributes

Genre: a particular type of composition marked by expected, conventional features

Attributes: a detail of appearance or associated possession that conventionally identifies a saint, deity, or other exalted personage in an iconography

As Catholic art developed, it established conventional genres of art based on popular biblical scenes. Keep in mind that a major didactic function of this work was to educate the massive majority of the Church faithful who could not read. Each of these genres has been composed by hundreds or thousands of artists over many centuries. Let’s look at some of Botticelli’s versions of six of the most common genres.

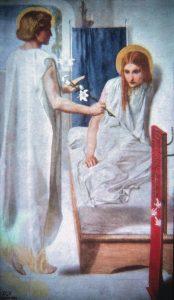

| The Annunciation: the angel informing Mary that she will bear the Christ | The Adoration of the Shepherds and Magi (Wise Men) at Jesus’ birth | Nativity: birth of Christ, with traditional ox and donkey |

|

|

|

| Annunciation. (1495) Tempera on panel. | Adoration of the Magi. (c 1476) Tempera on panel. | The Nativity. (c 1475). Fresco transferred to canvas |

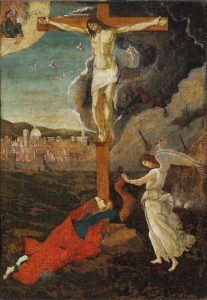

| Madonna and child: the Virgin Mary & baby Jesus, often with cousin John the Baptist | The Crucifixion: the dolorous scene of Christ upon the cross | Pieta: the grief of Mary and the Disciples over Jesus death |

|

|

|

| Madonna of the Rosebush. (1468). Tempera and oil on panel. | Mystic Crucifixion. (1495). Tempera on panel. | Pieta. (1495)Tempera on panel. |

As we have seen, Christian Icons depicted images of Saints, heroic souls of those who lived and died in the faith. These images include symbolic details that signify spiritual principles and references to the legendary lives of specific saints. Here are just a few among hundreds of conventional symbols (see Ferguson, 1961):

Halo, or Nimbus: a glow circling the head of the saint

Palm leaves: the Greco-Roman sign of victory, a symbolic references to Christ’s triumph over death and a Christian martyr’s faithful triumph over the death of the body

Fountain: a symbol of the Virgin Mary as the vessel through which eternal life in Christ flowed

Human heart: when carried by a saint, a symbol of love and piety; a “heart pierced by an arrow symbolizes contrition, deep repentance, and devotion under conditions of extreme trial” (Ferguson, 48-49).

Figures of specific saints are identified by Attributes: conventional remembrances of the saint’s life or death story. E.g. St. Lucy’s soul in heaven is traditionally shown holding a pair of eyes, referring to her sacrifice in tearing out her own eyes to alleviate the temptation experienced by a man haunted by them (Ferguson, 130).

|

|

| Francesco del Cossa, (c 1474). St. Lucy. Tempera on panel. | Sandro Botticelli. (1474). St. Sebastian. Oil on panel. |

Stories of martyrdom often include miraculous elements which at least temporarily delay the efforts of the persecutor. St. Sebastian is shown pierced with arrows, recalling his initial survival of Emperor Diocletian’s order that he be executed by archers. We need not, or course, understand all of these significations, but Christian icons will mean more as we know more of the lore.

Botticelli’s Mythography

Like other Renaissance painters, Botticelli composed scenes in sharply delineated times and places. But by the late 15th Century, time and space were becoming complicated.

|

|

|

| Adoration of the Magi. Detail: Medici Donors | Adoration of the Magi. (1478). Tempera | Adoration of the Magi. Detail: Painter. |

Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi fuses a religious scene with the contemporary landscapes and modes of dress of his day. This practice was becoming more and more popular, and it could be seen in devotional terms, the injection of biblical inspiration into the lives of believers.

But who are those people on the lower left? They are members of the Medici family, Botticelli’s patrons. And the lower gith figure gazing out at us? That’s a self-portrait of Botticelli.

|

|

| Masaccio. (1427). The Holy Trinity. Fresco. | Jan van Eyck. (1435). Madonna with Chancellor Rolin. Oil on panel |

As Christian art became more and more commonly sponsored by wealthy patrons, the practice of inserting portraits of the donors became more common. Masaccio’s donors are poised in the lower left and right, pulled back out of the plane of the Trinity. van Eyck’s Chancelor Rolin is depicted in his own palace sitting directly opposite the Virgin, enjoying the privileges of equal scale and the comfort of sitting.

The step from inclusion in a biblical scene to a dedicated portrait is a short one. The wealthy patrons of Renaissance art were happy to pay large sums of money to immortalize the images of themselves and their families. Botticelli was in great demand for portraits.

|

|

|

| Portrait of Woman (c 1462). | Portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici. (1480). Tempera on Wood | Portrait of Man Wearing a Medal of Cosimo the Elder. (1474). Tempera on Wood. |

Notice the focus on the Medici family, Botticelli’s patrons. An unidentified man holds a badge bearing the Medici emblem. Giuliano de’ Medici was killed in an assassination attempt aimed at his brother, Lorenzo the Magnificent, a great patron of the arts.

In a time when portraiture by a famous artist was staggeringly costly, art became a major weapon in mythologizing power. Palace art made competitive power statements that were intertwined with murderous political conflict. For the Medici, a major aspect of their aura was their sponsorship of Humanistic learning.

Thus Botticelli was often commissioned to compose, not biblical scenes, but scenes from Classical mythology. Medici sponsors knew their Ovid and other sources, and they embraced scenes like Pallas and the Centaur. A Centaur was a mythological creature that was half man, half horse. In Botticelli’s images, the beast is tamed and brought to peace and reason by Pallas Athena, Greek god of wisdom.

|

|

| Pallas and the Centaur. (1482). Tempera on Canvas. | La Primavera. [1] [Allegory of Spring]. (1478). Tempera on Wood |

Similarly, La Primavera depicts, not a biblical scene, but a seasonal transformation from Classical myth. The woman in the center is not the Madonna, but Venus, Roman name for Aphrodite, Greek goddess of love. Her son, Cupid (Eros) hovers above her while Mercury[2] looks skyward and the Three Graces[3] celebrate new life. To the right, a mythic miracle unfolds. The blue figure is Zephyrus, personification of the West Wind. His pursuing breath transforms Chloris, an incarnation of winter, into Flora, goddess of vegetation.

[1] Primavera is Italian for “First Green,” i.e. spring.

[2] Mercury: Roman name for Hermes, messenger of the gods, always shown with wings.

[3] Three Graces: in Greek mythology, goddesses representing charm, nature, beauty, goodwill, and fertility.

Botticelli’s Style

Botticelli maintains a treasured place in the hearts of lovers of European art. A major reason for this is his style. One can recognize a Botticelli figure at a glance: the elongated elegance, the impassive faces, the flawless features. His figures are meticulously drawn in mimetic fashion, but they also partake of the Greeks’ love of the human ideal of beauty.

|

|

| Madonna of the Rosebush. (1468). Tempera and oil on panel. | Dante Gabriel Rossetti. (1850). Ecce ancilla Domini! (Behold the handmaiden of the Lord!) |

Think about your ideals of human beauty. I’ll bet you see them in Botticelli’s figures. Four centuries after his time, the English painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti was still finding inspiration in the Florentine master.

References

Botticelli, S. (1475). The Adoration of the Magi. [Painting]. Florence: Uffizi Gallery. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/boticelli-adoration-lami

Botticelli, S. (1490). Annunciation [Painting]. Florence, Italy: Uffizi Gallery. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/annunciation-d9604d56-89bb-414c-ba3c-fd71f4d28eec Tempera on panel.

Botticelli, S. (1468). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist. [Painting]. Private collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/sandro-botticelli/the-madonna-and-child-with-the-infant-saint-john-the-baptist

Botticelli, S. (1474). Portrait of Man Wearing a Medal of Cosimo the Elder. [Painting]. Florence, Italy: Uffizi Gallery. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/sandro-botticelli/portrait-of-a-man-with-the-medal-of-cosimo-1474

Botticelli, S. (c 1495). Lamentation of Christ with Saints Jerome, John, Paul, Peter and the Three Marys [Painting]. Munich, Germany: Alte Pinakothek. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/sandro-botticelli/pity-1490

Botticelli, S. (1478) La Primavera. (The Allegory of Spring). [Painting]. Florence, Italy: Uffizi Gallery. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/botticelli-spring

Botticelli, Sandro. (1468). Madonna of the Rosebush [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée du Louvre. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010064999 tempera on panel

Botticelli, S. (c 1500). Mystic Crucifixion [Painting]. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Art Museums. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/sandro-botticelli/crucifixion Tempera and oil oncanvas.

Botticelli, S. (c 1475). Nativity [Painting]. Columbia, SC: Columbia Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Botticelli_Nativity.jpg

Botticelli, S. (c 1495). Pieta [Painting]. Munich, DE: Die Pinakotheken, AN 1075. https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/en/artwork/Y0GRlo7xRX

Botticelli, S. (1480). Portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici [Painting]. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/artworks/41671-giuliano-de-medici

Botticelli, S. (c 1485). Portrait of a Young Woman [Painting]. Florence, IT: Uffizi Gallery. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/sandro-botticelli

Botticelli, S. (c 1480). Pallas and the Centaur [Painting]. Florence, Italy: Uffizi Gallery. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/pallas-and-the-centaur

Botticelli. S. (1474). Portrait of Man Wearing a Medal of Cosimo the Elder [Painting]. Florence, IT: Uffizi Gallery. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/sandro-botticelli/portrait-of-a-man-with-the-medal-of-cosimo-1474 Tempera on wood

Botticelli, S. (c 1500). Saint Sebastian [Painting]. Berlin, Germany: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. AN 1128. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/sandro-botticelli/sebastian Oil on panel

del Cossa, Frncesca. (c 1474). Saint Lucy [Painting]. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, AN 1939.1.228. https://www.nga.gov/artworks/369-saint-lucy

Ferguson, G. (1961). Signs and Symbols in Christian Art. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Masaccio. (1427). The Holy Trinity [Fresco]. Florence, Italy: S. Maria Novella. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/masaccio/the-trinity-1428

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. (1850). Ecce ancilla Domini! (Behold the handmaiden of the Lord!) [Painting]. London, UK: Tate Gallery. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rossetti-ecce-ancilla-domini-the-annunciation-n01210

van Eyck, J. (1435). Madonna with the Chancellor Rolin [Painting]. Paris, FR: Louvre Museum. INV 1271; MR 705 https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010061856

a standard feature of art in a given genre that is expected and understood in the context of origin: e.g. a content, a style, a signification, a theme

A conventional system of significations that associate details of appearance with particular religious figures

a detail of appearance or associated possession that conventionally identifies a saint, deity, or other exalted personage in an iconography