7.3 Emerging Humanism

Vasari’s 1st Renaissance Period

On Giotto

Giotto di Bondone, Florentine painter and architect, is regarded as the founder of the central tradition of Western painting because his work broke away decisively from the stylizations of Byzantine art, introducing new ideals of naturalism and creating a convincing sense of pictorial space. His momentous achievement was recognized by his contemporaries: … in about 1400 Cennino Cennini wrote that “Giotto translated the art of painting from Greek into Latin and made it modern.” He was the first artist since antiquity to achieve widespread fame (Giotto di Bondone, 2004).

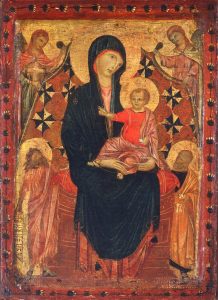

Breaking away from Byzantine style. Let’s return to our comparison challenge. You’ve already noted that Byzantine art almost always portrayed Christ, the Virgin and child, or saints as inert, impassive residents of a timeless theological realm in which nothing happened. This reflects the Medieval Church’s near monopoly on art and its fixation on sin and the afterlife. The current world was systematically dismissed as sin’s playground.

|

|

| Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. Tempera on panel. | Giotto di Bondone. (ca. 1304). Pieta. Fresco. |

By contrast, Giotto chooses to dramatize a narrative scene from the Bible in which the faithful are doing something, i.e. mourning the death of their Lord. The image presents, not a timeless theology, but actions of the faithful in this world. It embraces living human beings and a natural setting as worthy of note.

St. Francis: Humanized Faith

In the 13th Century, the Church of Rome was in serious trouble. Its profound levels of corruption and predatory financial practices were turning people away and feeding disillusion. Grasping abbots and bishops squeezed profits out of their lands and demanded tithes from desperately poor parishioners. They practiced arcane, incomprehensible rituals and theologies that bewildered and alienated the needy.

Then came Francis, a mendicant friar from Assisi in Umbria (Italy). Francise renounced his father’s wealth, assumed a life of wandering poverty, and helped to develop a form of Christianity that addressed the current world as God’s beloved quotation.

St. Francis of Assisi. (c 1294). Canticle[1] of Brother Sun and Sister Moon (Canticle of the Creatures)

Most High, all-powerful, good Lord,

Yours are the praises, the glory, and the honor, and all blessing,

To You alone, Most High, do they belong,

and no human is worthy to mention Your name.

Praised be You, my Lord, with all Your creatures, especially Sir Brother Sun,

Who is the day and through whom You give us light.

And he is beautiful and radiant with great splendor;

and bears a likeness of You, Most High One.

Praised be You, my Lord, through Sister Moon and the stars,

in heaven You formed them clear and precious and beautiful.

Praised be You, my Lord, through Brother Wind,

and through the air, cloudy and serene, and every kind of weather,

through whom You give sustenance to Your creatures.

Praised be You, my Lord, through Sister Water,

who is very useful and humble and precious and chaste.

Praised be You, my Lord, through Brother Fire,

through whom You light the night,

and he is beautiful and playful and robust and strong.

Praised be You, my Lord, through our Sister Mother Earth,

who sustains and governs us,

and who produces various fruit with colored flowers and herbs.

Praised be You, my Lord,

through those who give pardon for Your love, and bear infirmity and tribulation.

Blessed are those who endure in peace

for by You, Most High, shall they be crowned.

Praised be You, my Lord, through our Sister Bodily Death,

from whom no one living can escape.

Woe to those who die in mortal sin.

Blessed are those whom death will find in Your most holy will,

for the second death shall do them no harm.

Praise and bless my Lord and give Him thanks and serve Him with great humility.

[1] Canticle: i.e. a holy song of praise or hymn

The spiritual themes are obvious: humility, praise, faithfulness. From an artist’s perspective, however, consider the expanded field of possibilities for subject matter. Francis embraces sun, moon, earth, water, plants, animals and even the tribulations and experiences of people in this world. Possibilities for art abound.

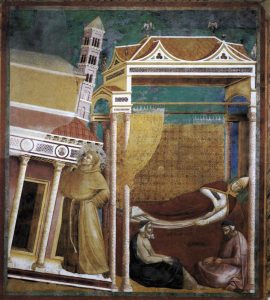

Giotto’s Legend of St. Francis

Giotto helped expand the range of subjects that became common in ecclesiastical art. His Pieta was an example of emerging genres of scenes depicting actions of the biblical faithful. But what of the centuries that followed? Byzantine icons had always celebrated the saints, but they were pictured in that inert, timeless heaven. What of their actual lives of faith?

Giotto made a special practice of focusing on the life of Francis. He did so in numerous venues, but especially in the upper story of the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi. The Legend of St. Francis series of frescoed bays lines the aisles of the nave.[1] Each presents a scene demonstrating Francis’s life of self-deprecating faith.

[1] Nave: the central portion of a church in which the laity stands or sits.

|

|

| Legend of St. Francis: (1290) Panel 5. Francis renouncing wealth. Fresco. | Legend of St. Francis: (1290) Panel 6. Dream of Innocent III. Fresco |

|

|

| Legend of St. Francis: (1290) Panel 15. Sermon to the Birds. Fresco | St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata. (c 1300). Tempera on Panel. |

Let’s notice a couple of contextual points. Francis was born into wealth but felt compelled to renounce his father’s life of luxury. The influence of his order of mendicant friars—i.e. monastic brothers who took vows of poverty and did not take official orders—rekindled an appreciation of Christianity throughout the Italian peninsula. The reform pope Innocent III (there’s a story!) claimed to have had a dream that Francis would help prop up the collapsing influence of the church.

Panel 15 illustrates Francis’s loving brotherhood with all creatures, accompanied by St. Clare, his associate. The final image shows Francis receiving from the spirit of Christ the stigmata, permanent marks indicating the five wounds of the crucifixion on hands, feet, and side.

Venues and Media

You’ll notice that our captions routinely make notes of the medium used for the work. Medium is related to venue: how and where an image is displayed. Most ecclesiastical art was used in one of four venues: manuscript illustrations, architectural icons (sadly, we have no time!) altar pieces, and wall illustrations.

Tempera: a paint medium that fixes pigment in egg yolk

Fresco: a painting medium in which tempera pigments are applied to wet, freshly applied plaster, which acts as a binding medium as it dries

Whether working in wet plaster (Fresco) or on wooden panels, most European painters worked in “egg tempera, in which the pigments of the paint are mixed (or ‘tempered’) with egg yolks.” Tempera provided a “vivid and luminous” effect but was limited in color options” (Tempera, 2005). It also dried fast, restricting brushwork and texture.

Matters of Form are always related to Medium. Tempera and Fresco shared two stylistic results. Colors were muted, especially in fresco, and details were often limited. In Section 7.5, we will see the results of a significant development in painting media.

Vital Questions

Context

Giotto played a transitional role in the emergence of the Renaissance. He reflects an emerging emphasis on the Human: the human dimensions of Christian faith and the natural world in which human beings live. While he does not yet channel a high degree of Greco-Roman learning, these interests do approximate the Classical interest in picturing the natural world.

Content

Three aspects of Giotto’s content are worthy of note:

Individualized human figures with increasingly precise detail

Dramatic action and human feeling

Situation of a scene in a natural setting with receding background space

Stay tuned.

Form

We have noted the significance of the media—especially fresco and tempera on panel—in which Giotto worked. Can you see how these materials affected the results?

References

Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art. Accession Number 1952.5.60. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.41675.html

Ferguson, G. (1961). Signs and Symbols in Christian Art. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Giotto di Bondone [Article]. (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Chilvers, I. (Ed.). Oxford UK: Oxford University Press https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-1431?rskey=jRfZmD&result=2

Giotto di Bondone. (ca. 1304). Pieta [Fresco]. Padua, Italy: Scrovegni Chapel. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.11661917

Giotto di Bondone. (c 1300). St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata [Painting]. Paris, FRL Musée du Louvre, INV. 309. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18119718 https://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18119718 Tempera on panel.

Giotto di Bondone. (c 1290). Legend of St. Francis: Panel 5. St. Francis renouncing worldly possessions. [Painting]. Assisi, IT: Basilica di S. Francesco. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13575227

Giotto di Bondone. (c 1290). Legend of St. Francis: Panel 6. Dream of Innocent III. [Painting]. Legend of St. Francis. Assisi, IT: Basilica di S. Francesco. Web Gallery of Art https://www.wga.hu/html_m/g/giotto/assisi/upper/legend/franc06.html

Giotto di Bondone. (c 1290). Legend of St. Francis: Panel 15. Sermon to the Birds. [Painting]. Legend of St. Francis. Assisi, IT: Basilica di S. Francesco. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.11662131

Giotto di Bondone. (ca. 1305). Annunciation to Mary [Fresco]. Padua, Italy: Capella degli Scrovegni. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13601600

Giotto di Bondone. (ca. 1305). Angel of the Annunciation [Fresco]. Padua, Italy: Capella degli Scrovegni. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13601600

Tempera [Article]. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Campbell, G. (Ed.). Oxford UK: Oxford University Press https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-3461?rskey=1loeWV&result=1

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative

a paint medium that fixes pigment in egg yolk to produce vivid effects. Popular in Europe before the development of oil paint, tempera dries quickly, compelling the painter to work rapidly and limiting the possible effects.

a painting medium in which pigments are applied to wet, freshly applied plaster, which acts as a binding medium as it dries

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate im-ages and actions in time and space