5.6 The Art of the Church

The Year the World Changed

|

| School of Raphael. (1508-1520). Vision of the Cross. Fresco. Detail. |

With its conquests, Rome changed, and was changed by, the worlds it absorbed into its imperial maw. In 312 CE, Constantine, Emperor of the Western realm of the Roman Empire, forged an alliance with Christian Bishops to support his wars with rival emperors. Twelve centuries later, Raphael da Urbino captured the key moment in the legend of Constantine being led by a vision of the Christian cross to victory in the crucial Battle of the Milvian Bridge. The alliance lasted. The Empire changed and was changed by an alliance made by the Emperor Constantine with bishops of a formerly obscure religious faith. Over the next several centuries, the Empire was Christianized and the Christian Church became Imperial. Neither would ever be the same.

Early Church Images

It would be wonderful to dig into the story of the Church and Empire, but our concern is with art. We have seen that the Hebrew tradition never depicted images of its God, Jehovah, as “graven images” would lead to the practice of idolatry which was forbidden by the Law of Moses. Christianity grew out of the Jewish faith. But its theology of Jesus as one of the persons of a unified God who was incarnated in the body of a man opened the door to depictions of the Son of God.

From their earliest days, Christians composed artistic images. Early Christian art reflected the ethos of small churches that met in private homes and tended to the needs of humble people, especially women and slaves. Most frequently, Jesus was depicted in Fresco as a good shepherd (see John 10) on the ceilings or walls of tombs.

|

| Christ as the Good Shepherd. (3rd C CE). Catacomb of Donna Velata. Ceiling Fresco. |

Let’s notice two things. First, the depictions of Christ made by the early church emphasized his humility. Shepherds occupied a very low rung on the social ladder. The image of a lowly shepherd protecting his flock with loving care parallels the gospels’ vision of a great lord who assumed a lowly place to save his children.

Second, notice that the Classical model of art is being left behind. The classical artist analyzed human visual experience to mimetically create the illusion of actual seeing. These images portray the figures of Jesus and the sheep with reduced mimetic detail. The figures are abstracted from any context of time, action, or emotional pathos. They are depicted for purely devotional reasons. Without suggesting any value judgment whatsoever, we can recognize that these images are not conceived according to a classical model of art.

Imperial Church; Imperial Christian Art

The alliance of Christian bishops with Emperors transformed the art of the Mediterranean world and, in time, of Northern Europe. The bishops’ single-minded focus on Christian themes gradually came to monopolize the patronage and practice of artists. On the other hand, the influence of the Empire transformed Christian ideology and its image of the Christ.

At the same time that he was allying with bishops, Constantine moved the imperial capital from Rome to a town called Byzantium which was strategically located on the Bosporus, a narrow strip of water separating the Western (European) and Eastern (Asian) worlds. He moved most of the treasures and art of Rome to the city which was renamed—what else?—Constantinople, the city of Constantine.

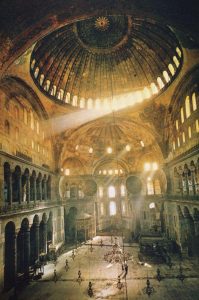

Constantine also began to build churches. Really big churches. Vast basilicas reconceived as public buildings reflecting the glory of the empire. In the 6th Century, the Emperor Justinian rebuilt the Cathedral of Constantinople. Hagia Sophia (The church of Holy Wisdom) was at the time one of the grandest buildings on earth with the largest dome. It testified to God’s grandeur, but even more directly to the power of the Empire that now equated its interests with Christ’s.

|

|

| Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom). (537 CE). Exterior view. | Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom). (537 CE). Interior rotunda. |

The interior of Hagia Sophia was lavished with gorgeous Mosaics. A mosaic is a visual composition comprised of thousands of colored bits of glass, stone, or gems called tesserae.

|

|

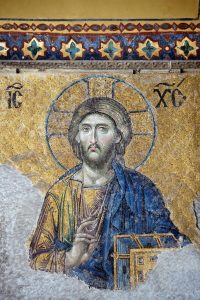

| Christ Pantocrator. (532-537 CE). Mosaic. Hagia Sophia. | Virgin and Child. (532-537 CE). Mosaic. Hagia Sophia. |

In these mosaics we again see a departure from the Classical model of art. Christ and the Virgin Mary are depicted in stylized, simplified form. Their impassive faces betray no reaction to any particular event and their bodies are posed in a timeless, abstracted stasis. We could see it as heaven or simply as an ideological formulation. We are clear on what we are seeing: figures we recognize for conventional reasons and theological signification. But we are not led to think about an act of seeing actual visual subjects in a moment of time and place. Jesus, after all, is frozen into the moment of his infancy in this and countless images into our own day of Mother and Child.

We must also notice the profound transformation of these figures. Jesus the humble shepherd has been reconceived as Christ Pantocrator, the imperial ruler of everything. Mary, the carpenter’s wife, is now enthroned as the Queen of Heaven. Heaven itself has mutated into an imperial court.

The Byzantine Tradition

The term Byzantine is applied to the eastern half of the Roman Empire, centered in Constantinople, formerly named Byzantium. Its Orthodox churches in northern Africa, Asia Minor, Greece, the Balkans, and, in time, Russia continue to this day to form an alternative to the Roman Catholic world.

The Christian Icon

In the Christian tradition, an Icon is a depiction of Jesus, the Virgin and child, or a saint which focuses worship. In the Orthodox and Catholic traditions, icons called the faithful to worship Christ, venerate[1] Saint Mary, confess to a priest, and partake of the Eucharist (communion). They facilitated personal, intercessory prayers to saints who had earned God’s favor and would pass the requests on to the one who could grant them. Icons have been and still are produced in the thousands for devotional display in churches or homes, on jewelry, or in a host of other applications.

| Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Theodore and George. (6th C CE). Encaustic on panel | St. Peter. (7th Century CE). Encaustic on panel |

By the way, let’s clarify the use of the phrase “Virgin and child” for anyone who might be wondering how a mother might be a virgin. While the Bible is by no means clear on this point, later tradition held that Mary was impregnated not by a man but by the intervention of the Holy Spirit.

We should notice a few conventional contents shared among these icons: Mary, Jesus arrested in permanent infancy, and attending angels or saints. The haloes indicate the status of the saint: a person who has died and been sanctified by faith or by notable acts of holiness including martyrdom or a particular holy life. As was true of Hindu art, saints are indicated by attributes: St. Peter is generally shown carrying a set of keys indicating his commission from Jesus (Matthew 16.18-19).

As important as icons were to devotion and intercessory prayer, they also instructed mostly illiterate worshippers in the faith. Attributes which identified the saints served a didactic purpose in reminding worshippers of the story of each saint’s spiritual heroics.

The functions to which icons are directed influence their form and style. The focus on theology and devotion leads to a representational technique that is more stylized than the classical emphasis on mimesis. Figures are abstracted, static and emotionless, devoid of any individuating features. They are frozen in a timeless present and the composition does little to indicate spatial depth. As we saw in Egyptian art, this timeless constancy affirms eternal authority, in this case that of God and the Queen of Heaven.[2]

[1] With little time to explicate the complex issue of veneration of saints, let’s try to summarize it briefly. The Church always condemned worship directed toward anyone but God. However, it encouraged believers to venerate saints who had earned special favor through martyrdom of holy living. Icons (holy images) of the saints and relics from their lives—bones, clothing, possessions—were used for intercessory prayer. The supplicant brought a request to the saint who resided in favor with God in the hope that God would be more likely to grant requests presented by favored saints. Art was deeply involved in these rituals.

[2] The Virgin Mary began to be venerated as the Queen of Heaven as early as the 3rd Century. This designation became a major focus in Medieval Christianity.

Rome and a Disintegrating West

As imperial force and wealth increasingly settled in Constantinople, its authority eroded in the European west. In the 5th and 6th Centuries, Germanic and Hunnish peoples flowed into the power vacuum of what would become Europe and the Western Empire dissolved.

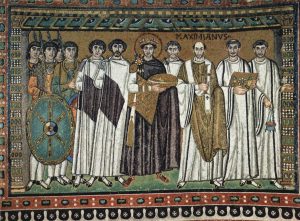

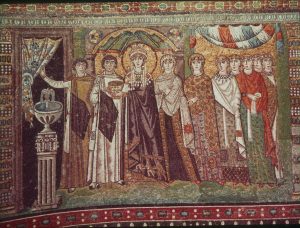

In the 6th Century, Emperor Justinian made a last effort to pull the West back into line. In the regional capital of Ravenna (a town on Italy’s Adriatic Coast) he built a magnificent Basilica with stunning mosaics.

|

|

| Basilica di San Vitale. (548 CE). Interior view | Christ the Redeemer. Apse Vault. Mosaic |

|

|

| Mosaic of the Donors: Justinian and his Court | Mosaic of the Donors: Theodora and her Court |

As you can see, the Byzantine style is persisting. We should note the remarkable distance Christian ideology has moved into an imperial model. Christ is sitting in imperial purple robes on an imperial throne that bestrides the world. Emperor and Empress are flanking the altar as if they convey devotional power in themselves. We might ask, how far has an imperial model of the church led later generations away from the values of the early church?

Despite Justinian’s efforts, Europe in the Middle Ages became increasingly dominated by Germanic cultures that assumed fragmented forms of authority, the so-called Feudal System.[3] These war lords had little interest in the classical tradition of scholarship. So they conceded much of the task of administration to the scholars of the Church of Rome. These scholars used Latin for everything. They read St. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible. They preserved a smattering of classical Latin scholarship. And they conducted the business of kings, dukes, counts and earls in Latin.

[3] Feudal System: Medieval scholars today question whether there ever really a Feudal System was. For our purposes, we can simply note that centralized Imperial authority was fragmented into only loosely associated local fiefs.

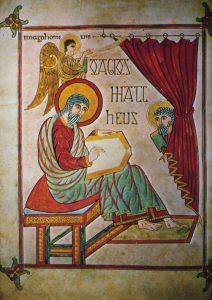

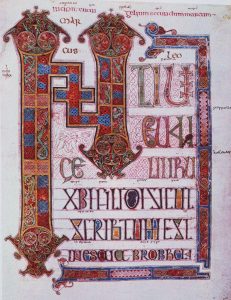

Much of the art produced in these centuries was composed by scribes as illustrations to manuscripts, hand printed copies of texts. Before the printing press, European texts were all inscribed by hand. Some editions of the Bible were lovingly and sumptuously illustrated by monks. The Book of Kells in Ireland and the Northumbrian (Northern England) Lindisfarne Gospels are beautifully preserved examples.

|

|

|

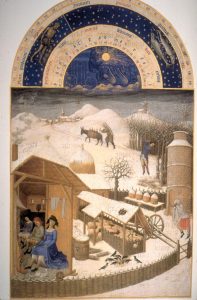

| Linisfarne Gospels. (c 698). Book of Matthew. | Book of Mark | Limbourg Brothers. (1416). February. Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Manuscript Illustration. |

A very small proportion of the population could read and fewer could afford the cost of a manuscript. However, medieval aristocracy often patronized scribes and artists to compose elaborately illustrated books of hours. These were devotional guides for the canonical ours of prayer observed in monasteries. In the sample of the book of hours of the Duc de Berry.

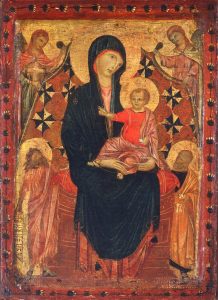

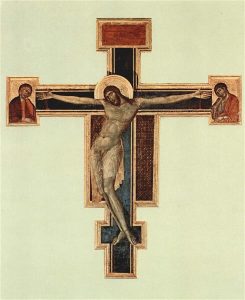

Through nearly 1,000 years, the Church of Rome almost completely dominated Europe’s cultural life. Artists were almost exclusively patronized by the church. Their primary role was to compose icons and devotional art for church architecture, altar pieces, and icons for the home. Through it all, the Byzantine style persisted, as we see in the work of a 13th Century Florentine artist named Cimabue. Can you see Byzantine conventional contents and stylistic orientations in his work?

|

|

|

| Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. (c. 1290). Tempera on panel. | Painted crucifix. (c 1274). | Madonna and Child Enthroned with two Angels 13th C). Tempera on panel. |

Vital Questions

By following the break with classical traditions that marked the emergence of Christian art in the Byzantine era, we must not fall prey to assumptions of value. Byzantine artists broke with the commitments of classical Greek and Roman artists, but they did so not because they regressed in skill or technique. Their idea of art’s function was profoundly different from that of Greek sculptors.

Context

You have probably taken note of the twin commitment of Byzantine art. It serves a didactic purpose in teaching and advocating for Christianity and for Empire. And it is committed to leading the faithful in devotions. These commitments shape its choices of content and of form.

Content

Byzantine art is quite limited in content. It repeats the same format again and again: Christ as world leader, the Virgin and child, noteworthy saints, and angels to convey an attitude of praise.

These contents are intimately intertwined with the significations of Christian theology. The more we know of the Bible and Christian tradition, the more these images make sense. Attributes identifying particular saints, for example, were chosen to instruct people who could not read in how to live by faith.

Form

As we have noted, Byzantine art assumed an ideological approach to the representation of figures. It simplified its forms in a stylized fashion. It fixed them in a flat space and a timeless present. Its formal features were directed to the task of teaching edifying piety.

The Byzantine style lasted a long time. Yet Cimabue trained an artist who was to break the Byzantine line and begin to recover the link to the classical past. We’ll follow this rebirth in the next module.

References

Basilica di San Vitale [Interior Photograph]. (545 CE). Ravenna, IT. bradhostetler (February 121, 2014). Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ravenna,_San_Vitale_-_12521189753.jpg

Book of Mark [Illustration]. (c 698). Lindisfarne Gospel. London, UK: British Museum. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St._Mark_-_Lindisfarne_Gospels_(710-721),_f.93v_-_BL_Cotton_MS_Nero_D_IV.jpg

Book of Matthew [Manuscript Illustration]. (c 698). Lindisfarne Gospel. London, UK: British Museum. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LindisfarneFol27rIncipitMatt.jpg

Bust of Julius Caesar [Sculpture].(1st century BCE). front view. Berlin, Germany: State Museum of Berlin. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caesar-Altes-Museum-Berlin.jpg

Christ as Good Shepherd [Fresco]. (3rd C CE). Rome. IT: Catacomba di Callistus; Crypt of Lucina. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Good_shepherd_02b.jpg

Christ Pantocrator [Mosaic]. (532-537 CE). Istanbul, Turkey. Hagia Sophia. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/byzantine-mosaics/christ-pantocrator-867

Christ the Redeemer [Mosaic]. (548 CE). Apse Vault. Ravenna, Italy: Basilica di San Vitale. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/byzantine-mosaics/st-vitalis-archangel-jesus-christ-second-archangel-and-bishop-of-ravenna-ecclesius-547

Cimabue. (c 1288). Crucifix [Painting]. Florence, IT: Uffizi Gallery. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/cimabue/crucifix-1288Hagia Sophia. (532-537 CE). Istanbul, Turkey. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Ayasofya.

Cimabue. (13th C). Madonna and Child Enthroned with two Angels [Painting]. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/cimabue/virgin-enthroned-with-angels-1295 Tempera on panel.

Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art. Accession Number 1952.5.60. https://www.nga.gov/artworks/41675-madonna-and-child-saint-john-baptist-saint-peter-and-two-angels

Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom). (537 CE). Exterior view. Istanbul, Turkey. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Ayasofya

Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version. (2021). Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-Revised-Standard-Version-Anglicised-NRSVA-Bible/#booklist

Limbourg Brothers. (1416). February. Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry [Manuscript Illustration]. Folio 2v. Chantilly, FR: Chantilly: Museé Condé. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Les_Tr%C3%A8s_Riches_Heures_du_duc_de_Berry_f%C3%A9vrier.jpg

Mosaic of the Donors: Justinian and his Court [Mosaic]. Ravenna, Italy: Basilica di San Vitale. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/byzantine-mosaics/emperor-iustinianus-and-his-suite-547

Mosaic of the Donors: Theodora and her Court [Mosaic]. Ravenna, Italy: Basilica di San Vitale. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/byzantine-mosaics/mosaic-of-theodora-547

Saint Peter with Saints Hermagoras and Fortunatus (Crypt vault fresco). (c. 1180). Basilica Aquileia, Italy. Sailko. (N.D.). Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Basilica_di_aquilieia,_cripta,_affreschi_volta_03.JPG

School of Raphael. (1520-1524). Vision of the Cross (Fresco-Detail). Vatican City: Sala di Costantino, (Raphael Rooms). https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/stanze-di-raffaello/sala-di-costantino/visione-della-croce.html

St. Peter [Icon]. (4th-7th Century CE). Mount Sinai, E.G.: Saint Catherine’s Monastery. WikiArt. https://www.wikiart.org/en/orthodox-icons/saint-peter-550

Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Theodore and George, with Angels [Icon]. (6th C CE). Mount Sinai, Egypt: Monastery of Saint Catherine. WikiArt. https://www.wikiart.org/en/orthodox-icons/virgin-theotokos-and-child-between-saints-theodore-and-george-550

Virgin and Child [Mosaic]. (532-537 CE). Istanbul, Turkey. Hagia Sophia. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/byzantine-mosaics/the-virgin-and-child-theotokos-mosaic-in-the-apse-of-hagia-sophia-867

a painting medium in which pigments are applied to wet, freshly applied plaster, which acts as a binding medium as it dries

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

a wall or floor design composed of 1,000s of chunks of colored clay, stone, or glass (tesserae). Popular in the Greco‐Roman world and in Byzantine art.

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

art styled in the manner of Byzantine icons: depictions of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or saints in a stylized manner—flat, emotionless, timeless, placeless, focused on theological dogma. Common Byzantine media: mosaics, frescoes, paint on panel

1) an image which signifies a holy figure for worship or devotion. 2) a Christian image of Jesus or saints which focuses worship and prayer. 3) a Byzantine genre of holy mosaics and paintings that depicts holy figures according to a conventional style. 4) In contemporary scholarship, an image that signifies a conventional meaning recognized by an audience despite the absence of any visual resemblance.

an aspect of art which is expected and understood by the audience in a particular tradition

a detail of appearance or associated possession that conventionally identifies a saint, deity, or other exalted personage in an iconography

a quality of art that instructs its audience on information, ways of life, or social, moral, religious, or political principles

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

a consistent pattern of choices regarding form and technique that comprise an identity for an artistic tradition, movement, or individual vision

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc

a representational technique that depicts the idea of a visual subject through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis