5.4 Classical Rome

In the last section, we said that many European and American cultural roads lead back to Greece. Yet we have only Roman copies of many works of art. And the fact is that those cultural roads passed through a major detour: Rome.

Beginning in the 3rd Century BCE, Roman military legions and navies began to conquer lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. In the 1st Century BCE. It conquered the two powers that had descended from Alexander’s conquests: the Seleucids in the Aegean and the Ptolemies in Egypt and North Africa. The Greek world was swallowed by the Latin.

Now, a distinctive of Roman rule was its willingness to recognize, tolerate, and in many cases adopt cultural features of its conquered peoples. In the case of Greek heritage, one might almost say that while Rome conquered Greece militarily, Greece conquered Rome culturally. Rome adopted Greek philosophy, science, medicine, architecture, and art to an astonishing degree. Wealthy Roman families hired Greek philosophers to tutor their children.

In the case of art, the influence was immense. While Greek art is often lost to time, it frequently survives in faithful Roman copies. Scholars still debate whether Laocoön is a Greek original or a Roman copy.[1]

|

| Bust of Julius Caesar. (1st century BCE). Green granite and white glass. |

When they weren’t copying Greek models, Roman sculptors often applied mimetic techniques to portraiture, as in this bust of Emperor Julius Caesar. We remember that Greek artists used “realistic” visual techniques to depict an abstracted ideal of the perfect human figure. Roman artists often addressed themselves to an enterprise rare in the ancient world, the depiction of individual human beings with distinctive facial features. In genuine portraiture, the artist captures individuals’ unique appearances and character, recognizable to those who know them. Actual appearances rarely conform to those Greek ideals. A good portrait will encompass the “flaws” that comprise the person, as exemplified here in the powerful Caesar’s balding pate

Roman cultural syncretism—the blending of cultural traditions—can be poignantly seen in the funerary art of Romano-Egypt.[2] For about 3 centuries, northern Africa, centered in Alexandria, provided the grain which fed the Empire. Roman citizens owned plantations which grew the grain using slave labor. Over this time, the cultures fused, as they tend to do in colonial contexts.

[1] The subject matter of Laocoön testifies to the complexity of Greco-Roman cultures. The story of Laocoön is told in the Aeneid, an epic narrative grafted by the Roman poet Virgil onto Homer’s Greek epic the Iliad. Homer sings of the Greek heroes who conquered the city of Troy. Virgil tells of a Trojan warrior who survives the war and goes on an epic journey leading to the founding of Rome. The poem coopts Greek myth to infuse Rome’s origin story in Greek tradition.

[2] The story is very complex, and firm rule was only established by Augustus Caesar after the death of Julius. However, Cleopatra’s alliance with Caesar and then Marc Antony placed the kingdom firmly in the Roman orbit.

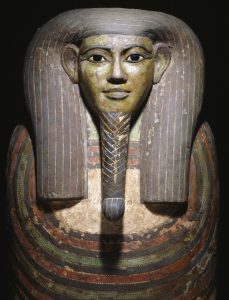

Of course, Egyptian culture is famous for embalming deceased bodies. A mummy was traditionally housed in a sarcophagus with an effigy placed over the face within. These traditional effigies were highly stylized, with little attempt to depict the individual faces of the deceased.

|

|

| Coffin of Horankh. (c. 700 BCE). Wood, paint, bronze. | Coffin of Horankh. Detail |

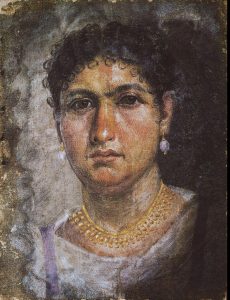

Mummies from the Romano-Egyptian period were transformed by the values of portraiture. In place of the idealized figures of traditional Egyptian coffins and mummies, Romano-Egyptian funerary art remembered the individual appearance and personality of the deceased. These images were composed using encaustic, a solution of pigment in hot wax applied to canvas or, more often, wood.

|

|

| Funerary portrait of the boy Eutyches. (2nd C CE). Encaustic on wood | Funerary portrait of a girl. (2nd C BCE). Encaustic on wood |

|

|

| Funerary portrait of Aline (c 50 CE). Tempera on canvas | Funerary Portrait of Man with Beard. (2nd C BCE). Encaustic on wood. |

| Funerary Portrait of a Girl. (2nd C BCE). Encaustic on wood. |

Egyptian mummies had always sought to preserve life and project it into infinity. Now, mummies preserved for grieving families haunting images of lost loved ones. These faces peer out at us startlingly life-like intensity. They match the poignant memories of our family photo albums today.

References

Bust of Julius Caesar [Sculpture].(1st century BCE). front view. Berlin, Germany: State Museum of Berlin. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caesar-Altes-Museum-Berlin.jpg

Coffin of Horankh [Painting]. (c. 700 B.C.). Dallas, TX: Dallas Museum of Art. https://www.dma.org/art/collection/object/3304922

Funerary portrait of a 4-year-old girl [Painting]. (2nd C Ce). Munich, GE: Egyptian Museum. Captmondo. (November 22, 2014). Photograph. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mummy_of_a_Four_Year-old_Child_-_Roman_Period_-_%C3%84S_1307.jpg

Funerary portrait of Aline [Sarcophagus Painting]. (c 50 CE). Hawara, Egypt. Berlin, Germany: State Museum of Berlin. https://recherche.smb.museum/detail/607538/mumienportr%C3%A4t-der-aline?language=de&question=R%C3%B6misch-%C3%A4gyptische+Mumie&limit=15&sort=relevance&controls=none&conditions=AND%2Btitles%2B&collectionKey=AMP*&collectionKey=AMPAgyptischesMuseum&collectionKey=ANT*&objIdx=8

Funerary portrait of the boy Eutyches [Sarcophagus Painting]. (2nd Century CE). Fayyum, Egypt. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 18.9.2. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547951Funerary Portrait of a Man with a Beard [Painting].

Funerary portrait of a man with a beard [Sarcophagus Painting]. (2nd C CE). Fayyum, Egypt. Windsor, UK: Myers Collection, Eton College. Forget, Y. (N.D.).). Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Homme_avec_barbe,_portrait_fun%C3%A9raire,_Fayoum,_%C3%89gypte.jpg

Funerary portrait of a girl [Sarcophagus Painting]. (2nd Century CE). Fayyum, Egypt. Frankfurth am Main, GE: Liebieghaus. https://liebieghaus.de/en/antike/mummy-portrait-girl