5.2 Asian Classical Traditions

In the lead section of this chapter, we argued that many dominant social groups develop Classical aesthetic traditions that reflect their claims to cultural superiority. These claims may be open to question or even offensive to groups within the society. Yet the dominance of the group confers an authority to the classical tradition that can pervade the culture.

In our first week, we explored a stable artistic style that dominated Egypt for roughly 2,000 years. The permanence of that style conferred authority on dynasties that rose and fell over the centuries. Some had foreign origin and others reflected social collapse and the rise to prominence of lower social orders. Yet all adopted that classical Egyptian style of art to affirm the perpetual blessing of the gods and the annual flood of the Nile. We can find similar affirmations of social prominence in Asian cultures.

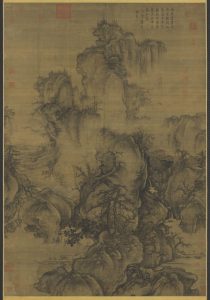

Chinese Landscape Painting

What Genres of painting can you think of? Portraits? History paintings? Religious Icons? What about Landscape? Do you like images that reflect the beauty of a picturesque vista? Did you know that landscapes were rare until Li Ch’eng pioneered the form during the Song Dynasty?

|

||

| Li Ch’eng. (10th C.) Solitary Temple amid Clearing Peaks. Ink on silk. | Xi Guo. (11th C CE). Early spring . Ink on Silk Scroll | Tang Yin. (c. 1510). Seeing Off a Guest on a Mountain Path. |

Take a moment to look at these paintings. They share quite a few features, don’t they? By comparing them, we can recognize the force of an artistic genre: a conventional type of art that features shared contents and styles which a familiar audience will expect and understand. What conventions—shared features—can you find in the images?

Take some time to look. Seriously. Maybe jot some observations down. What features do Ch’eng, Guo, and Yin share?

Observing … Jotting …

Observing … Jotting …

Observing … Jotting …

OK, I know you are compiling a perceptive list. Maybe something like this?

- Elongated rectangular boundaries

- Monochromatic colors: a narrow range of hues, browns and blacks

- Similar visual subjects: mountain, water, human habitation, minimized human figures

- Spatial zones: minimized foreground, looming middle distance, vanishing background

- Zones of negative space, cloudy, mysterious emptiness

We can quickly see that these features are shared within the genre. They include matters of content and of form. But what do these features signify? For that, we need context. You may, as I do, lack a great deal of knowledge about Chinese cultural history. If so, let’s recall what we have said about bridging the Context Gap: when we encounter work from a context we know little about, we should …

- Try to see the works for what they are.

- Hold our initial responses loosely, opening to fresh perspectives.

- Notice indicators of cultural gaps: might that feature mean something else in the culture of origin?

- Gather whatever background information is available.

- See the works afresh in light of what we have learned.

- Make an honest assessment of how we wish to respond.

A “Classical” Chinese Aesthetic

In compiling a list of shared, conventional features, we pretty much cover the first three steps of our process. But the significance of those elevated vistas, those misty, open zones may require a bit of research.

The landscape genre arose during the Song dynasty of imperial rule. Established in 960 CE, Song rule re-established stability after a chaotic period of internal warfare, the so-called Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The Song were conquered by the Mongol Kublai Khan, whose Yuan dynasty ruled China from 1271 to 1368, when the Ming dynasty restored Chinese rule.

At a glance, we can imagine that, throughout this period, the question of cultural identity would arise. What does it mean to be Chinese? Buddhist and Confucian religion, the legacy of bureaucratic organization, and art would all help maintain what we might very loosely term a “classical” cultural tradition.

In a 2017 article, Van Thi Diepp provides a Westerner like me with my minimal knowledge of Chinese cultural a primer on the traditional Chinese aesthetic that guided Ch’eng and others in developing the genre of landscape painting.

The vista of the immaterial

Diep warns Westerners that, to see these paintings from the cultural inside, they must consider landscape from a substantively different perspective. In a landscape by John Constable or Claude Lorrain, we see a close observation of picturesque geographical features. But, says Diep, the core Chinese concept is different.

Mountain and water.

We noticed that our paintings shared visual subjects, especially mountains and water. DO these subjects have special significance? Well, yes: “The Chinese character for valley, gŭ 谷,” explains Diep (p. 81), “is derived pictorially from a flowing River and not as the space between mountains.”

Diep’s observations inform us that Chinese script consists of characters derived from pictograms. In Chinese culture, calligraphy forms the core skill leading to literacy, education, and art. Traditionally, Chinese painters began with calligraphy and developed their techniques using ink and paper. Paintings featuring ink on paper are not surprisingly, often monochromatic (displaying a limited range of colors).

So, mountain and water. What is it about these conventional elements that inspire not only landscape paintings, but the essence that defines the whole idea of a valley? Here is Diep:

Chinese paintings depict landscapes not merely to celebrate natural beauty, but also to evoke spiritual exaltation. These artists invite us to see portals into the infinite. Furthermore, they insert a reflective, enlightened human perspective directly into the scene:

A Scribal culture

You’ll notice that Diep’s discussion of paintings refers to calligraphy, the art of composing manuscript text. Of course, Chinese writing is itself comprised of ideograms which fuse drawn images with abstracted ideas. Chinese painters first learn calligraphy, and the border between image and text is permeable. You’ll notice that verses usually form portions of a Chinese painting.

As we consider the formal features of these landscape paintings, the elongated, rectangular boundaries, the muted colors, we must think of the media: long silk or paper scrolls inscribed with pen and ink. Chinese painting is generally found on scrolls either hung vertically or rolled out horizontally. And the limited color palettes are related to a scribal orientation.

Indeed, traditional Chinese culture was oriented toward scribal discipline. The Confucian tradition was steeped in scribal scholarship and philosophy which were adopted as the tenets of civilization and the bureaucratic basis on which empires and businesses were run. The scribe’s pen gives birth to painting and art inhabits the very nature of Chinese text.

A Classical Genre

Chinese artists have worked in many Media and Genres. Some Chinese traditions of painting focused on depicting the aesthetic splendors of aristocratic life. Others depict mythical realms of action among gods and demons. But the landscape genre turns resolutely away from both the elegant luxuries of the elite and the squalor of poverty. Human perspective is reduced to temples of meditation compressed into a minimized foreground and, occasionally, tiny figures with scholarly or monkish aspirations.

Landscape paintings, then, affirm the highest, Classical ideals of Chinese culture. Buddhism offers enlightenment as the fruit of a pilgrimage out of the self and into the mystery of the transcendent. Confucianism and Taoism both call for the individual to rise above selfish indulgence and surrender to the principles of heaven.

So let’s return to the paintings. We noticed mountains, water, minimized humanity, and open zones of emptied space. Our brief foray into the paintings’ context helps us follow the thematic Signification of these Conventions, doesn’t it? Banal human life, minimized in mere traces of human presence, fades against spectacular natural vistas. Vertical composition lifts our eyes to the heavens and mountaintop elevations into spiritual enlightenment. Mystical voids seem to open out into the mysteries of infinity.

The final step calls us to decide what we will think. I see in these paintings core Aesthetic qualities, beauty, harmony, balance. I do feel the inspiration pictured in those elevated and open spaces. I am touched by the minimized but persevering figures of people toiling toward enlightenment though dwarfed in an enormous world. I feel much of this on a first look while a return to the works armed with some information leads me at least minimally across the contextual bridge to share universal human concerns.

What do you see?

Japanese Samurai Culture

What do you think of when you hear the word Samurai? Well, Japan, for sure. Probably a culture of warfare expressing itself in martial arts and elegant swords. But Samurai culture is more than that. And every aspect of it is infused with art.

In the 12th Century, the Japanese warrior class gained dominance over a society which had been ruled by a traditional aristocracy which considered itself to be classical. Establishing an exclusive right to bear arms, it formed a hereditary caste that ruled the society. As do many ruling elites, the Samurai asserted its right to rule by adopting a code of civilized conduct “regulated by Bushido (Warrior’s Way), a strict code … of loyalty, bravery, and endurance” (Samurai).

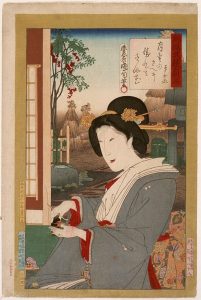

|

|

| Samurai. (1801 – 1806). Color woodcut |

Westerners who have heard the term usually think of Bushido as a matter of warfare. Of course, it is that. Yet samurai culture was far more comprehensive. It sought aesthetic cultural refinement in every area of life.

A “Classical” Japanese Aesthetic

So far, what we are learning about Samurai culture fit in with our notion of classicism. It governs a way of life recognized as superior and civilized to an elite social class claiming authority. But what about art?

The thing is, Japanese culture doesn’t necessarily recognize a distinction between art and the rest of life. In an article on Japanese aesthetics, Ryōsu Ōhashi explains that 3 influences—Chinese Confucianism, Zen Buddhism, and the Shinto religion—coalesced in a commitment to a refined style of life. “Aesthetic egalitarianism,” claims Ōhashi, applied to all areas of life, martial arts, fine arts, and everyday arts: cooking, eating, bathing and entertaining visitors. Even the basest areas of life were raised to elegance through art and ritual.

Japanese aesthetics are deftly expressed in the tea ceremony, a “highly ritualized gathering of people” that sought four Zen principles: “harmony, purity, tranquility, and reverence.” Ritualized conventions govern not only the drinking of the tea, but the utensils that serve it, the architecture of the teahouse, and its connection with formal gardens.

|

|

| Yasuimoku Komuten Company (2001) Facsimile of a Japanese Teahouse | Toyohara Kunichika. (1883). Tea Ceremony. Color Woodblock Print. |

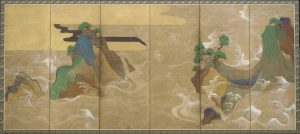

Harmony. Purity. Tranquility. Reverence. Well, the unceasing churn of the seashore is not in itself very tranquil or pure. But Tawaraya Sōatsu’s silkscreen of waves breaking on rocks is fused with the calm that many of us feel when losing ourselves in the sounds of the sea. Sōatsu plays with not necessarily natural colors and forms, blending browns and tans into a warm, soothing span just touched with blue chill and green life.

|

| Tawaraya Sōatsu. (circa 1600-1628). Waves at Matsushima. Right panel of folding screen. |

Haiku: Poetics of Indirection

We have said that a classical aesthetic is often marked by restraint, discipline, and indirect communication. In Japanese culture, civilized refinement lies in one’s ability to communicate with cool restraint, intimating rather than boorishly exclaiming emotions and messages. Turning to a distinctive poetic form, we can see evidence of the preference for “Implication, Suggestion, Imperfection” that Ōhashi attributes to the Japanese sense of beauty haiku.

Now, according to Ueda (2014), classifying haiku as Classical would be tricky. This verse form challenged an earlier classicism, using humor “to liberate poetry from aristocratic court culture.” Yet the genre’s longevity and preference for implication would seem to support our recognition of its classical features.

The Haiku is a short, simple poetic form. Its simplicity commends it to many elementary school curricula, and American school children may recall studying and even writing poems in three lines with precisely seventeen syllables.

Let’s sample the work of master “Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) who, according to Ueda. “elevated haiku to a mature poetic form by setting up high aesthetic ideals.” Now, let’s remember that we are reading translations from a language sharing few phonetic features with English.[1] Here is how our translator conveyed Bashō’s composition:

[1] Translations of poetry are always extremely difficult. In addition to construing the sense of the lines, a translator of verse is faced with the daunting task of devising rhythms and figures of speech that emulate the idioms of the original language.

crow is sitting

his autumn eve.

I know. You like assigned poems that are this short. But there’s a lot to see here. The plain sense of the poem appears to be straightforward. The words visualize a poignant scene: branch, crow, autumn evening. But what about Signification?

Let’s recall the three themes that Ōhashi specifies: “Implication, Suggestion, Imperfection.” And Ueda identifies two haiku ideals:

sabi (loneliness) reinvented by Bashō, as “the pleasure of loneliness” as in “two old men” watching cherry blossoms who have “learned to accept the mutability of life.”

karumi (lightness) which contrasts with the “‘heavy’ beauty” of “a poem dealing with a weighty philosophical theme

“Yet, it is not the opposite of ‘heaviness’” warns Ueda, “rather, it is a dialectical[2] transcendence[3] of it.” Haiku center on images of nature caught in seasonal moments which deftly suggest themes of mortality and the passing nature of time:

A successful haiku does not attempt to describe things in detail. … The writer (or observer) is only half of the process: the reader is the other half. Every haiku is almost asking the reader to be a poet too, by hopefully triggering an emotion or reaction. Haiku do not include the poet’s reaction to what is being observed. They hope to evoke a response in the reader from recorded observations (Ōhashi).

| Matsuo Bashō. (c 1644-1694). Poetry Painting. Ink wash on paper |

Haiku composed by the 17th Century master Matsuo Bashō

An ancient pond!

With a sound from the water

Of the frog as it plunges in.

The cry of the cicada

Gives no sign

that presently it will die.

An ancient pond!

With a sound from the water

Of the frog as it plunges in.

The cry of the cicada

Gives no sign

that presently it will die.

O ye fallen leaves!

There are far more of you

Than ever I saw growing on the trees!

Tis the first snow—

Just enough to bend

The gladiolus leaves!

How did your reading go? Perhaps you had a nice experience of ennui, of somber beauty. Yet this deceptively complex form has complex rhythms, as Ōhashi explains:

The “cutting word” in haiku is often found at the end of the 1st or 2nd line. This rhythmic break encourages us to compare the 1st and 2nd images or themes. Below, the weary traveler’s yearning for rest is crosscut by a sudden vision transcending weariness. Structure and rhythm open up thematic contrasts. Can you see them?

In search of an inn—

Ah! these wisteria flowers!

Vital Questions

Context

Art with classical orientations links to cultural contexts that make some claim to merited authority. They evoke a notion of disciplined, elegant behavior that is thought to be civilized, often in opposition to rival or subordinate social groups who are disdained as primitive or uncouth.

Confronting a classical culture across a wide contextual gap requires us to do a bit of research to get the signification of conventional contents and forms. Doing so, we need to keep in mind the limits of our familiarity. As a compiler of these materials, I enthusiastically confess the limit of my knowledge of Asian cultures. I have tried to be open to my sources and I hope I don’t get too much wrong.

Still, it is perhaps remarkable how much of our experience cross the bridge fairly readily. Chinese landscape painting and Japanese Haiku are perpetually popular among Western audiences. I feel readily able to connect to many of their features and forms. How about you?

Content

These landscapes and short poems help us clearly understand the concept of genre. We have seen that Chinese landscape paintings conventionally contain certain contents: mountain, water, minimized human figures, and blank spaces. Traditional haiku generally place a reader’s reflective mind in a seasonal nature scene.

The significations that arise from these contents are also conventional: the turning of the seasons, human limitations and mortality, the vastness of the world, and the immanence of eternity. These themes arise as stably and profoundly as Christian spirituality arises from church art.

Form

At first glance, the forms of these compositions seem strictly controlled by conventional rules. The scale of human habitation on a vertically looming mountainside with unfilled gaps. Seventeen syllables in three lines with a cutting word marking a thematic shift. Artists and poets have been following these rules for centuries.

And yet, these rules provide a framework for endless creative flexibility. Think of the haiku. Just a few words saturated with suggestive implication. The creative possibilities of such a form are endless. And people are still writing in haiku today.

References

Bashō, M. (17th Century). Selected haiku. Trans. Aston, W. G. (1899). A History of Japanese Literature. London: William Heinemann. Wikisource https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Author:Matsuo_Bash%C5%8D.

Basho, Matsuo. (circa 1644-1694). Poetry Painting. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/57339 Ink wash and color on paper.

Ch’eng, Li. (10th Century). Solitary temple amid clearing peaks [Painting]. Kansas City, MO: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/painting-li-cheng-a-solitary-temple.php Hanging scroll. ink and light color on silk

Diep, V. T. (2017). The landscape of the void: Truth and magic in Chinese landscape painting. Journal of Visual Art Practice, 16(1), 77-86.

https://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=121504878&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Guo, X. (11th C CE). Early spring [Painting]. Taipei, Taiwan: National Palace Museum. https://www.npm.gov.tw/Exhibition-Content.aspx?sno=04011674&l=2#lg=lg0&slide=1 Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guo_Xi_-_Early_Spring-800×1159.jpg

Kinkoku, Yokoi. (after 1799). Portrait of Basho. Hanging scroll, ink and light color on paper. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Museum of Art. ID Number: AAPD 7874. https://umma.umich.edu/objects/portrait-of-the-poet-basho-1968-2-22/

Kunichika, Toyohara. (1883). Tea ceremony (Color woodblock print). In Daily Life of Tokyo Women. CA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Accession number M.74.104.2. https://collections.lacma.org/node/190750

Li, Ch’eng. (10th century). Solitary temple amid clearing peaks [Painting]. Kansas City, MO: Nelson Atkins Museum of Art. https://art.nelson-atkins.org/people/8540/li-cheng/objects

Ōhashi, Ryōsuke,. (2014). Japanese Aesthetics [Article]. Trans Parkes, G. In Kelly, M. Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780195113075.001.0001/acref-9780195113075-e-0302?rskey=WPiZZQ&result=3

Samurai [Color woodcut]. (1801 – 1806). San Francisco, CA: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. ID FASF.23250. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15055293

Sōtatsu, Tawaraya. (circa 1600-1628). Waves at Matsushima. Right panel of folding screen. Washington D.C.: Freer Gallery. Smithsonian National Museum of National Art. Accession number. F1906.231. https://asia.si.edu/explore-art-culture/collections/search/edanmdm:fsg_F1906.231-232/

T’ang, Yin. (1516). Imitation of the Tang people. [Painting]. Retrieved from https://www.wikiart.org/en/tang-yin/-11516.

Tang, Y. (ca. 1505-1510). Seeing off a guest on a mountain path [Painting]. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum. https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/23342

Tea ceremony [Article]. (2004) Keown, Damien, Ed. A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780198605607.001.0001/acref-9780198605607-e-1816

Ueda, Makoto. (2014). Haiku [Article]. [Article]. In Kelly, M. Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. Oxford University Press https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780199747108.001.0001/acref-9780199747108-e-350

Yasuimoku Komuten Company Ltd. (2001). Japanese Teahouse. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. G225 Gallery. Retrieved from https://collections.artsmia.org/art/59614/teahouse-yasuimoku-komuten-company-ltd.

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

a particular type of composition marked by expected, conventional features: e.g. Japanese haiku, Chinese landscape painting, Renaissance sonnet

in visual art, a composition that represents a human subject as an individual, meticulously capturing physical or psychological likenesses

A) an image which signifies specific religious content for devotion and ritual. B) a Christian image of Jesus, Mary, or the saints which in the Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions focuses worship and prayer. C) a Byzantine genre of Christian mosaics and paintings.

a visual composition that represents outdoor scenery that may or may not include human structures. Often an exercise in perspective and depth of field, with receding zones: foreground, middle distance, and deep distance.

the material projected by art for the reader’s mind and imagination. Content can consist of an immediate Subject—e.g. a figure in a painting or a story in a narrative—and Signification, a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

the situation of a work of art in a cultural, historical, or personal setting which shapes media, materials, techniques, and meanings for the artist and also the audience

an uncomfortable clash in perspective between art’s context of origin and the context from which the audience experiences it

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

a standard feature of art in a given genre that is expected and understood in the context of origin: e.g. a content, a style, a signification, a theme

the dimension of an artistic experience that appeals to or challenges an au-dience’s sense of taste and experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A response distinct from “interested” concerns such as ideology, sexuality, social conflict or economics

a Japanese poetical genre in which 17 syllables deftly evoke a poignant, often seasonal nature scene that shifts with a cutting word into a thematic reflection on life