4.4 Songs of Broken Hearts

Singing Stories: Ballads

Exalted literature often concerns itself with the experiences of the aristocratic elite. Lyric poetry like “The Lady of Shallot” channels stories that stretch beyond their narrow boundaries.

Another Genre of poetry that tells stories is that of the Ballad. Unlike the lyric, a ballad tells a more or less complete story. Traditionally, Folk Ballads were sung where common folk gather and the characters represented lower rungs on the social ladder. For centuries, ballads were composed, sung, and revised by bards singing in taverns and inns. No one wrote them down, and bards felt free to express their poetic talents in their own versions of popular standards. Thus, no one version could be “authoritative.”

|

| Thomas Rowlandson. (19th Century). The Ballad Singers. Drawing & Watercolor. |

In the 16th Century, printers sold books to the learned but experimented with other genres for a commonplace audience. A Broadside Ballad fixed a particular version of a previously oral ballad on a large, single sheet of paper. Some of these continue to be sung today by folk singers. Many tell stories of love’s heartbreak, often the grief of one lamenting the oldest heartbreak on earth: a lover’s mortality.

For a long time, traditional folk tales and ballads were despised as common and inferior by the highly educated literary world. However, as we saw in Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott,” 19th Century poets began to embrace folk traditions such as the ballad.

The Unquiet Grave

Ballads were sung and eventually published throughout Ireland, Scotland, England, and Wales. These folk songs crossed the Atlantic with emigrants to the British colonies and formed the spine of folk and bluegrass music among Scotch Irish and Celtic North Americans. Even today, you can walk into a Celtic pub and enjoy the wail of fiddles and the crooning of modern bards conferring their own takes on traditional ballads. You might hear a bard singing “The Unquiet Grave.”

“The Unquiet Grave” (15th Century?)

The wind doth blow today, my love,

And a few small drops of rain;

I never had but one true-love,

In cold grave she was lain.

I’ll do as much for my true-love

As any young man may;

I’ll sit and mourn all at her grave

For a twelvemonth and a day.

The twelvemonth and a day being up,

The dead began to speak:

“Oh who sits weeping on my grave,

And will not let me sleep?”

“’T is I, my love, sits on your grave,

And will not let you sleep;

For I crave one kiss of your clay-cold lips,

And that is all I seek.”

“You crave one kiss of my clay-cold lips,

But my breath smells earthy strong;

If you have one kiss of my clay-cold lips,

Your time will not be long.

“’T is down in yonder garden green,

Love, where we used to walk,

The finest flower that e’re was seen

Is withered to a stalk.

“The stalk is withered dry, my love,

So will our hearts decay;

So make yourself content, my love,

Till God calls you away.”

Listen to Luke Kelly’s performance of the ballad

“The Unquiet Grave” illustrates themes common to traditional ballads. Such songs celebrate heroic ideals of true love, but the challenge in them is very often the perpetual human enemy, death. In such ballads, lovers are separated by death, but the living lover remains perennially faithful, often loitering about by a gravesite haunted by the spectral voice of the beloved.

Ballad of Frankie and Johnny

Are you a folkie? Or do you prefer American music with African American roots? In slavery-haunted America, Black musicians exorcised their people’s demons with songs that dealt with the violence of the world they inhabit. Many of the resulting songs were ballads telling stories of heartbreak.

In 1899, a woman named Frankie Baker shot and killed her unfaithful lover, Allen Britt, in St. Louis. Within a year, the ballad “Frankie Killed Allen” had been composed by Bill Dooley and published by Hughie Cannon.

More popularly titled “Frankie and Johnny,” the song has been sung by scores of artists and dramatized in several films. Thus, despite the original publication, there is no authoritative version. All, however, share variants of the haunting refrain that speaks for millions of women in many ages and cultures: “He was my man, and he done me wrong.”

|

| Mississippi John Hurt in the Library of Congress Recording Laboratory. (March 17, 1964). |

The 1929 version by Mississippi John Hurt shines as an example of Delta-style Blues. Here is the text of Hurt’s version of the ballad.

Mississippi John Hurt (1928) “Frankie and Johnny”

Frankie and Johnny was sweethearts, O Lord how did they love.

Swore to be true to each other, true as the stars above.

He was her man, he wouldn’t do her wrong

Frankie went down to the corner, just for a bucket of beer.

She said “Mr. Bartender, has my lovin’ Johnny been here?

He’s my man, he wouldn’t do me wrong.”

“I don’t want to cause you no trouble, I ain’t gonna tell you no lie.

I saw your lover an hour ago with a girl named Nellie Bly.

He was your man, but he’s doin’ you wrong.”

Frankie looked over the transom, she saw to her surprise:

There on a cot sat Johnny, makin’ love to Nellie Bly.

“He’s my man, and he’s doin’ me wrong.”

Frankie drew back her kimona, she took out a little .44.

Rooty-toot-toot three times she shot right through that hardwood door.

Shot her man; he was doin’ her wrong.

“Bring out the rubber-tired buggies, bring out the rubber-tire hack.

I’m takin’ my man to the graveyard, but I ain’t gonna bring him back.

Lord, he was my man, and he done me wrong.”

“Bring out a thousand policemen, bring ’em around today.

Then lock me down in the dungeon cell and throw that key away.

I shot my man, he was doin’ me wrong.”

Frankie said to the warden, “What are they going to do?”

The warden said to Frankie “It’s electric chair for you,

‘Cause you shot your man, he was doin’ you wrong.”

This story has no moral, this story has no end.

This story just goes to show that there ain’t no good in men.

He was her man, and he done her wrong.

This version of the ballad raises interesting issues of Point of View. Remember that a Narrative is a telling of a story. The Narration is the voice (or movie camera) which presents the story and shapes our view of it.

In this ballad, the Persona, or narrating voice, is that of a Third Person Narrator who stands. Nevertheless, Frankie, the primary character (protagonist?) is given a great deal of text to speak from her perspective. The contrast between her passions and convictions and the world weary Irony of the Narrator is striking.

The Point of View dynamic alters significantly in Lena Horne’s 1955 recording of the song. In this obnhighly produced and lushly orchestrated version, the entire song is presented in First Person Narration, that is, in Frankie’s voice: “He was my man, but he done me wrong.” This perspective fuses the Persona with the main character, heightening the Pathos of the ballad while reducing the Irony of an observing but detached Narrator.

Singin’ Da Blues

The American songbook has been deeply influenced by African American musical and literary traditions. Early American folklore and songs blended Euro-American idioms with the rhythms of Africans forcibly imported as slaves. By the early 20th Century, African American music was beginning to establish an astonishing level of influence over all of American pop music. Not surprisingly, the music of a people enslaved and then denied full citizenship is full of heartbreak.

African American musicians, as slaves and as “freedmen,”[1] developed three traditions of startlingly innovative composition. “Negro spirituals” were sung in churches and on concert stages around the world. Jazz music was developed to entertain patrons of brothels and evolved into a transcendent form wedding individual expression with mutually supportive partnership. And, to ease the breaking heart, the Blues were sung in shabby juke joints where Black laborers gathered on Saturday nights to release the tensions of long work weeks and subservience to oppressive masters.

from Howlin’ Wolf’s “I asked her for water” (1956).

Oh, I asked her for water, oh, she brought me gasoline.

That’s the troublingest woman//That I ever seen.

[1] Freedmen: the term used after the Civil War for slaves liberated by the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The most pervasive traditions of American music today—rock and roll, rhythm and blues, reggae, hip hop, and many dimensions of contemporary country—descend at least in part from the blues.

Rick Darnell and Roy Hawkins (1969) “The Thrill is Gone”

The thrill is gone

The thrill is gone away

The thrill is gone baby

The thrill is gone away

You know you done me wrong baby

And you’ll be sorry someday

The thrill is gone

It’s gone away from me

The thrill is gone baby

The thrill is gone away from me

Although, I’ll still live on

But so lonely I’ll be

The thrill is gone

It’s gone away for good

The thrill is gone baby

It’s gone away for good

Someday I know I’ll be open armed baby

Just like I know a good man should

You know I’m free, free now baby

I’m free from your spell

Oh I’m free, free, free now

I’m free from your spell

And now that it’s all over

All I can do is wish you well.

Listen to the performance by the great B. B. King.

|

| Heinrich Klaffs. (1971). B. B. King at Audimax, University of Hamburg. Photograph. |

Thematically, notice that the lamentation in this blues arises from the death of passion, the other side of passion’s coin. Initially, it seems so powerful in its promise of euphoria. But, it doesn’t seem to last. And as lovers learn generation after generation, it doesn’t offer much as a foundation for a lasting relationship. “The thrill is gone.”

Like Hebrew verse, a blues stanza uses repetition for emphasis, memory, and developing elucidation. Line 2 more or less repeats line 1. Line 3 takes things further. And line 4 resolves the tension. In this case, the stanza carries the repetition over 4 rather than 2 lines. Repeated blues lines linger like the throbbing pulses of heartbreak.

Torch Songs

It is difficult to empathize with the frustration felt by Ovid’s Phoebus lusting after Daphne or King David’s power play against a married woman. But the all-too-common outcome of passion, invoked over the centuries by many artists, is the heartbreak of unrequited love.

Torch Song: derived from the phrase “to carry a torch” for someone, a song lamenting the pain of lost love. Often a ballad which dramatizes the despair of a woman in thrall to a no-good man, though the gender roles can be reversed. The lamenting lover suffers from infidelity, neglect, or even violence

Scores of popular songs from the 20th Century qualify as torch songs, often sung by women: “Body and Soul,” “Stormy Weather,” “I Got it Bad (and that Ain’t Good),” “Can’t help Lovin’ Dat Man,” “Am I Blue” and many more. In “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” a song from the 1933 musical Roberta, passion burns to smoke and ash.

Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach. (1933) “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”

They asked me how I knew,

My true love was true,

Oh-oh-oh-oh, I, of course, replied,

“Something here inside,

Cannot be denied.”

They said, “Someday you’ll find,

All who love are blind.

Oh-oh-oh-oh, when your heart’s on fire,

You must realize,

Smoke gets in your eyes.”

So I chaffed them,

And I gaily laughed,

To think they could doubt my love.

Yet today, my love has flown away.

I am without my love.

Now, laughing friends deride,

Tears I cannot hide.

Oh-oh-oh-oh, so I smile and say,

“When a lovely flame dies,

Smoke gets in your eyes.”

Smoke gets in your eyes.

Listen to the great Sarah Vaughn’s performance of the song.

|

| W. P. Gottlieb, W. P. (August 1946) Portrait of Sarah Vaughan. Café Society. Photograph. |

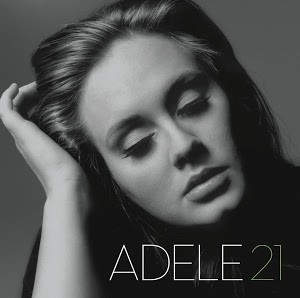

Torch songs maintain their appeal into more recent times. In 2011, Adele recorded a monster hit that poignantly captures the heartbreak and weary resolution of a left-behind lover encountering the lost beloved.

|

| Adele. (2011). 21. Album Cover. |

Adele and Dan Wilson, D. (2011). “Someone like You.”

I heard that you’re settled down

That you found a girl and you’re married now

I heard that your dreams came true

Guess she gave you things I didn’t give to you.

Old friend, why are you so shy?

It ain’t like you to hold back or hide from the lie

I hate to turn up out of the blue uninvited

But I couldn’t stay away, I couldn’t fight it

I hoped you’d see my face & that you’d be reminded

That for me, it isn’t over.

Never mind, I’ll find someone like you

I wish nothing but the best for you two

Don’t forget me, I beg, I remember you said:

“Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead”

Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead, yeah.

You’d know how the time flies

Only yesterday was the time of our lives

We were born and raised in a summery haze

Bound by the surprise of our glory days.

I hate to turn up out of the blue uninvited

But I couldn’t stay away, I couldn’t fight it

I hoped you’d see my face & that you’d be reminded

That for me, it isn’t over yet.

Never mind, I’ll find someone like you

I wish nothing but the best for you two

Don’t forget me, I beg, I remember you said:

“Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead”, yay.

Nothing compares, no worries or cares

Regrets and mistakes they’re memories made

Who would have known how bittersweet this would taste?

Never mind, I’ll find someone like you

I wish nothing but the best for you two

Don’t forget me, I beg, I remembered you said:

“Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead.”

Never mind, I’ll find someone like you

I wish nothing but the best for you two

Don’t forget me, I beg, I remembered you said:

“Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead”

Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead, yeah.

It probably isn’t difficult to process the themes and dynamics of these two lyrics. Using our approach to poetry, we can read the plain sense of the words and fairly quickly determine who is speaking to whom. The first song reflects, perhaps inwardly, perhaps to an unidentified listener, the musings of one whose confident trust has been shattered. The second dramatizes an encounter between two one-time lovers, unnamed, but deftly realized.

About now, however, you should be in a position to track the poetic structures of the songs. Our old friends, Parallelism, Anaphora, and sheer poetic repetition are here. But notice also the Rhyme Scheme and triple beat lyrics in “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” The patterns are looser in “Someone like You,” but don’t miss the occasional rhymes that provide thematic emphasis.

The Spent Passions of Crazy Jane

In his later years, William Butler Yeats’ composed spare, hard-hitting verse that packed the punch of both disillusionment and wisdom, doubt and enduring hope. In 1932, Yeats published Words for Music Perhaps, exploring the link between literary verse and song lyrics. In that collection, he composed a series of poems expressing the jaded life view of Crazy Jane, a woman who has walked the path of life from passionate youth to sterile old age. “Crazy Jane and the Bishop” is no torch song. But it profoundly probes the bitter ashes of broken love.

William Butler Yeats. (1932). “Crazy Jane and the Bishop”

I met the Bishop on the road

And much said he and I.

`Those breasts are flat and fallen now

Those veins must soon be dry;

Live in a heavenly mansion,

Not in some foul sty.’

“Fair and foul are near of kin,

And fair needs foul,” I cried.

“My friends are gone, but that’s a truth

Nor grave nor bed denied,

Learned in bodily lowliness

And in the heart’s pride.

“A woman can be proud and stiff

When on love intent;

But Love has pitched his mansion in

The place of excrement;

For nothing can be sole or whole

That has not been rent.”

In her dialogue with the Bishop, Jane deals with the smug superiority of a religious prude who glories in her physical decay, chiding her for having trusted (he imagines without knowing) the power of her physical beauty. But Jane knows that the world is more complex, more paradoxical than narrow, graceless piety will allow. Where does love “pitch his tent”?

Vital Questions

Context

Passion’s heartbreak is probably universal to every human context. In our sampling of heartbreak’s songbook, however, we can distinguish between two broadly understood contexts.

- “High” literature: traditions associated with cultural elites and steeped in academic knowledge

- Folk traditions: songs and ballads that directly the language and experience of non-aristocratic people who have limited access to academic knowledge

Of course, this opposition is largely nonsense. Shakespeare for example was a jobbing actor from a middling background who composed one of the world’s greatest bodies of writing drawing on a very limited degree of schooling. High literature that becomes lost in arcane snobbery soon descends into banal insignificance. And many an unschooled lyricist achieves breathtaking levels of poetic expression.

Still, tensions between the two poetic worlds are worthy of notice. Sometimes, authors on one side or the other express disdain for the opposition. And the forms of the writing do differ in fascinating ways.

Content

One way or another, all our songs of heartbreak tell stories. Lyrics suggest narrative backgrounds for their reflections. Dramas, epics, and ballads tell complete tales. And all mourn for the failure of love, either through the loved one’s indifference, betrayal, or mortality. Love stories share a narrative core.

But these narratives also raise thematic questions. Is love’s potential heartbreak worth risking? Is heartbreak a good reason to retreat into despairing isolation? How does one deal with a lover’s betrayal? How does one continue to live after one’s beloved passes away?

Form

By now, you should be getting clear on core terms: lyric, epic, ballad, drama. Hopefully, you are becoming skilled in hearing poetic rhythms. Tennyson’s “Lady of Shallot,” for example, has a fascinating stanzaic form: can you hear the rhymes? Can you sense the rollicking rhythms of the meter? (We’ll nail that concept down as we go along.) Remember—approaching a poem:

1. Read the poem out loud, listening for and feeling its rhythms and patterns of sound.

2. Read the plain sense of the poem: who is talking to whom about what?

3. Track patterns of sense and meaning that suggest deeper signification: i.e. themes.

References

Adele and Wilson, D. (2011). “Someone like You.” On 21. New York: Columbia Records. https://lyricstranslate.com/en/Adele-someone-you-lyrics.html

Bluesman Mississippi John Hurt in the Library of Congress Recording Laboratory [Photograph]. (March 17, 1964). Washington DC: Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/folklife/guide/nationalproject.html

Gottlieb, W. P. (c August 1946) Portrait of Sarah Vaughan, Café Society [Photograph]. Washington DC: Library of Congress. LC-GLB23- 0882. https://loc.gov/item/gottlieb.08821

Horne, L. (1955). Frankie and Johnny. On It’s Love. New York: RCA Victor Records. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UVHNX8SUp30

Hurt, J. (1929). “Frankie and Johnny.” https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/27238655/Mississippi+John+Hurt

Hurt, J. (1929). “Frankie and Johnny.” [Audio Recording]. On Beyond Patina Jazz Masters. Beyond Patina Records. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtxyjOFLXSg

Jerome, K. and Harbach, O. (1933) “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” In Roberta. https://www.lyricsplayground.com/alpha/songs/s/smokegetsinyoureyes.html

Kelly, L. (c 1970). The Unquiet Grave [Musical Recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jyqBA_Qr3qs

Klaffs, Heinrich. (1971). B. B. King at Audimax, University of Hamburg [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:B.B._King_3011710048.jpg

Rowlandson, T. (18th-19th Century). The Ballad Singers [Watercolor print]. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for British Art. AN B1977.14.367. https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:5755

The Unquiet Grave [Poem]. (15th Century?). Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50403/the-unquiet-grave#poem

Vaughn, S. (1958). “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” [Audio Recording]. On No Count Sarah. Em Arcy Records. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AybhBOqyQHQ

Yeats, William Butler. (1932). “Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop.” In Words for Music, Perhaps. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43295/crazy-jane-talks-with-the-bishop

a relatively short poem which expresses the deep reflections and poignant emotions of the poetic voice. Origin: the portion of ancient Greek dramas sung to the accompaniment of a lyre (harp).

a particular type of composition marked by expected, conventional features: e.g. Japanese haiku, Chinese landscape painting, Renaissance sonnet

a poem or song that tells a story. Traditionally, oral poetic genres compiled anonymously within folklore traditions for audiences with limited literary education

a traditional story in song or verse composed, adapted, and performed over a long time by bards and their audiences. Folk ballads reflect the life of common people, often marked by themes of grief and loss.

a printing of a traditional Folk Ballad which 18th and 19th Century people could purchase affordably. By printing one of many versions of a traditional ballad, a Broadside tended to fix the song and establish a semi-official version.

the viewpoint of a work of art’s content imposed on an audience by its structure and composition. In Narrative, the perspective of the narration. In a painting or photograph, the angle and scale from which the subject is depicted.

a telling of a story using some medium: prose, poetry, cinema, painting, etc.

the “voice” which conveys a story to its audience: a dictating voice, a cinematic camera, a dramatic painting, etc.

the voice, identity, and point of view to which we attribute a literary text. In ancient Greek, the mask worn by actors on stage.

a narrative told from the point of view of a character who stands outside the action, never participating in story events. Third person narration avoids us-ng I or We to refer directly to its persona, but it frequently invites the read-er to identify with a character's point of view by sharing the character's inner thoughts and feelings.

(or Hero) the rival in a story’s agon (central conflict) with whom we positively identify and sympathize

an often wryly humorous, indirect mode of communication that asks the reader to compare what is said with some known or signified reference. Frequently used to puncture false pretentions, especially of the social elite. E.g. a standup comedian who relies on the audience to draw on what it knows about a celebrity to get the joke.

the identity to whom we attribute a narrating voice and the point of view from which the story is told and understood. Note, single narratives can be told by multiple narrators: e.g. Emily Brontë (1847) Wuthering Heights; Wilkie Collins (1868) The Moonstone.

a narrative orientation in which the narrator’s voice is attributed to a char-acter within the story, a significant actor, an observer, or both.

the Greek term for emotion. In ancient Greek art, the emulation of human emotion and experience within the appearance of human figures

a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms

a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses: e.g. “I have a dream …” phrase repeated in Dr. Mar-tin Luther King’s speech, (8/28/1963).

within a poem, a repeated pattern of sounds that end lines, defining stanzaic boundaries and shaping a poem’s themes. Designated for analysis by letters: e.g. a-b-a-b, in which a-lines and b-lines end in rhyming words.