4.2 Passion’s Victims

The anguish of passion’s heartbreak can come from two directions. Perhaps the most destructive is the impact on a target of assault by unwanted passion.

Ovid: The Assault and Metamorphosis of Daphne

About 8 BCE, the Roman poet Ovid composed a collection of tales called the Metamorphoses. These poems channeled stories from Greek Myth. The word metamorphosis means transformation. Many of the tales in the collection involve magical transformations of people into animals or plants as a result of interactions with the gods.

Many of these tales also involve obsessive, destructive sexual passions. Often, they portray the quasi-human deities of the Greek pantheon lusting after beautiful mortals. As is common in Greek myths, quarrelsome gods determine the fates of humans or of less powerful deities. The sun god Phoebus (Greek name: Apollo) spats with Cupid (Greek name: Eros), son of Venus (Greek name Aphrodite), goddess of love. Cupid decides to teach Phoebus a lesson with his arrow of love:

Ovid. (c 8 CE). The Metamorphoses. from “The Tale of Daphne and Phoebus”

Daphne, daughter of a River God was first beloved by Phoebus great God of glorious light. ‘Twas … out of Cupid’s vengeful spite that she was fated to torment the lord of light.

For Phoebus … beheld that impish god of Love upon a time when he was bending his diminished bow, and voicing his contempt in anger said; “What, wanton boy, are mighty arms to thee, great weapons suited to the needs of war? The bow is only for … those large deities of heaven whose strength may deal mortal wounds to savage beasts of prey; and who courageous overcome their foes. …. Content thee with the flames thy torch enkindles … and leave to me the glory that is mine.”

Undaunted, Venus’s son replied, “O Phoebus, thou canst conquer all the world with thy strong bow and arrows, but with this small arrow I shall pierce thy vaunting breast!” … From his quiver he plucked arrows twain,[1] one love exciting, one repelling love. The dart of love was glittering, gold and sharp; the other had a blunted tip of lead; and with that dull lead dart he shot the Nymph[2] (Daphne), but with the keen point of the golden dart he pierced the bone … of the God.

Immediately the one with love was filled, the other … rejoiced in the deep shadow of the woods. … The virgin Daphne… denied the love of man. Beloved and wooed she wandered silent paths, for never could her modesty endure the glance of man or listen to his love. Her grieving (River God) father spoke to her, “Alas, my daughter, I have wished a son in law, and now you owe a grandchild to the joy of my old age.” But Daphne[3] only hung her head to hide her shame. The nuptial torch seemed criminal to her. … “My dearest father let me live a virgin always.” …

[1] Arrows twain: i.e. a pair of arrows

[2] Nymph: in Greek mythology, a minor female deity who personifies some aspect of nature

[3] Daphne: a nymph associated with freshwater rivers and springs

Two arrows, one of gold, one of lead. The first strikes loving passion into the heart of the target. The other fills its target with loathing. Now you know where those valentines with Cupid’s arrows come from!

OK, let’s slow down a bit. We have a complex Plot structure to deal with. First, we have conflict (Agon) between two Greek gods, Phoebus (Apollo) and Cupid (Eros). Out of that conflict arises the predatory pursuit of a young woman by a powerful male.

Phoebus when he saw her waxed distraught and, filled with wonder his sick fancy raised delusive hopes, and his own oracles deceived him. As the stubble in the field flares up, … so was the bosom of the god consumed, and desire flamed in his stricken heart. …

Swift as the wind from his pursuing feet the virgin fled, and neither stopped nor heeded as he called; “O Nymph! O Daphne! I entreat thee stay, it is no enemy that follows thee. … I am not a churl—I am no mountain dweller of rude caves, nor clown compelled to watch the sheep and goats. … My immortal sire is Jupiter.[4] The present, past and future are through me in sacred oracles revealed to man, and from my harp the harmonies of sound are borrowed by their bards to praise the Gods. … The art of medicine is my invention, and the power of herbs; but though the world declare my useful works there is no herb to medicate my wound.” …

The Nymph with timid footsteps fled from his approach, and left him to his murmurs and his pain. Lovely the virgin seemed as the soft wind exposed her limbs, and as the zephyrs fond fluttered amid her garments, and the breeze fanned lightly in her flowing hair. She seemed most lovely … and mad with love he followed … and silent hastened his increasing speed. As when the greyhound sees the frightened hare flit over the plain:—With eager nose outstretched, impetuous, he rushes on his prey, and gains upon her till he treads her feet, and almost fastens in her side his fangs. … So was it with the god and virgin: one with hope pursued, the other fled in fear.

[4] Jupiter: Roman name for the Greek god Zeus, king of the gods on Mt. Olympus

We’ve seen this movie, right? Powerful predator male pursues and overpowers a woman with no interest in his advances. Daphne escapes, right? Well let’s see.

Her strength spent, pale and faint, with pleading eyes she gazed upon her father’s waves and prayed, “Help me my father, if thy flowing streams have virtue! Cover me, O mother Earth! Destroy the beauty that has injured me, or change the body that destroys my life.” Before her prayer was ended, torpor seized on all her body, and a thin bark closed around her gentle bosom, and her hair became as moving leaves; her arms were changed to waving branches, and her active feet as clinging roots were fastened to the ground— her face was hidden with encircling leaves.—

Phoebus admired and loved the graceful tree. … He clung to trunk and branch as though to twine his form with hers, and fondly kissed the wood that shrank from every kiss. … “Although thou canst not be my bride, thou shalt be called my chosen tree, and thy green leaves, O Laurel! shall forever crown my brows, be wreathed around my quiver and my lyre; Roman heroes shall be crowned with thee, … and as my youthful head is never shorn, so, shalt thou ever bear thy leaves unchanging to thy glory.”

Here the God, Phoebus Apollo, ended his lament, and unto him the Laurel bent her boughs, so lately fashioned; and it seemed to him her graceful nod gave answer to his love.

On the one hand, we can read this tale as an Origin Story, a tale whose narrative logic provides an explanation for some aspect of the world. Can you spot the aspect of the natural world whose existence is accounted for by this story?

On the other hand, it dramatizes the all-too-human dynamics of the dark side of sexual passion. Indeed, we could see it as an attempted rape, thwarted only by a magic which kills Daphne’s personhood. Can you see these dynamics in the relationships around you, or even in your own experience? Narrative traditions in many cultures explore themes of desire, loss, and the costs of failed love.

|

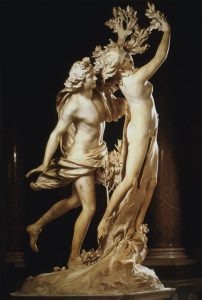

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini. (1622-1624) of Daphne’s transformation. Marble. |

The climactic moment of Ovid’s tale is captured by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, a master artist of Baroque Italy. Bernini’s marble figure repays close inspection. Unfortunately, the photograph captures only one view—there is nothing like walking around this or any other sculpture in person. Even in the photograph, however, the dynamic energy rising from inert marble is remarkable: Phoebus’ striving, Daphne’s desperate resistance, and then the shimmering emergence of magical energy as Daphne’s fingers begin to sprout leaves. Formally, the elegant, sweeping lines curve in rising, diagonal uplift. It’s an astonishing vision.

King David’s Lethal Passion

We have seen David’s great glory in ascending to the throne of Israel. Under David’s leadership, the ancient Kingdom of Israel reached an unprecedented political prominence in the region. In the biblical accounts of his career, he is celebrated as a virtuous hero, a “man after God’s heart.” Many of the Psalms which lead the faithful in worship are attributed to him.

But David was also a great sinner. In the passage below, see David being led into genuine evil—lust, adultery, and murder—by the passion of a voyeur looking upon a woman’s body.

David’s Great Sin: 2nd Samuel, 11.2-12.24

Late one afternoon, when David rose from his couch and was walking about on the roof of the king’s house, that he saw from the roof a woman bathing; the woman was very beautiful. When David inquired about the woman, it was reported, “This is Bathsheba daughter of Eliam, the wife of Uriah the Hittite.” So David sent messengers to get her, and she came to him, and he lay with her. … The woman conceived; and she sent and told David, “I am pregnant.”

So David sent word to Joab, “Send me Uriah the Hittite.” And Joab sent Uriah to David. … David said to Uriah, “Go down to your house, and wash your feet.” Uriah went out of the king’s house …but slept at the entrance of the king’s house … and did not go to his house.

When they told David, “Uriah did not go down to his house,” David said to Uriah, “You have just come from a journey. Why did you not go down to your house?” Uriah said to David, “The ark and Israel and Judah remain in booths, and my lord Joab and the servants of my lord are camping in the open field; shall I then go to my house, to eat and to drink, and to lie with my wife? As you live, and as your soul lives, I will not do such a thing.”

Then David said to Uriah, “Remain here today also, and tomorrow I will send you back.” … The next day, David invited him to eat and drink in his presence and made him drunk; and in the evening he went out to lie on his couch, … but he did not go down to his house.

In the morning David wrote a letter to Joab: … “Set Uriah in the forefront of the hardest fighting, and then draw back from him, so that he may be struck down and die.” … The men of the city came out and fought and some of the servants of David … fell. Uriah the Hittite was killed as well. … When the wife of Uriah heard that her husband was dead, she made lamentation. When the mourning was over, David sent and brought her to his house, and she became his wife, and bore him a son.

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi. (c.1640). David and Bathsheba. Oil on canvas. |

During the Italian Renaissance, the image of David ogling Bathsheba in her bath inspired many a painter who wished to dramatize a biblical scene while gratifying the male hunger for the female form. Artemesia Gentileschi’s more complex, restrained interpretation of the moment reflects a woman’s viewpoint. As we will see in a later chapter, Gentileschi brought to conventional subjects of the day the perspective of a woman who had herself experience the horror and shame of rape. It’s a powerful image, eh?

As we know all too well today, the sins of the great and powerful often go unpunished. But Uriah and Bathsheba had a champion—the prophet Nathan.

But the thing that David had done displeased the Lord, and the Lord sent [the prophet] Nathan to David. He came to him, and said to him,

There were two men in a certain city, the one rich and the other poor. The rich man had many flocks and herds; but the poor man had nothing but one little ewe lamb, which he had bought. He brought it up, and it grew up with him and with his children; it used to eat of his meager fare, and drink from his cup, and lie in his bosom, and it was like a daughter to him. Now there came a traveler to the rich man, and he was loath to take one of his own flock or herd to prepare for the wayfarer who had come to him, but he took the poor man’s lamb, and prepared that for the guest who had come to him.

Then David’s anger was greatly kindled against the man. He said to Nathan, “As the Lord lives, the man who has done this deserves to die; he shall restore the lamb fourfold, because he did this thing, and because he had no pity.”

Nathan said to David, “You are the man! Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: I anointed you king over Israel, and I rescued you from the hand of Saul; I gave you your master’s house, and your master’s wives into your bosom, and gave you the house of Israel and of Judah; and if that had been too little, I would have added as much more. Why have you despised the word of the Lord, to do what is evil in his sight? …Now therefore the sword shall never depart from your house, for you have despised me, and have taken the wife of Uriah the Hittite to be your wife.

Thus says the Lord: I will raise up trouble against you from within your own house; and I will take your wives before your eyes, and give them to your neighbor, and he shall lie with your wives in the sight of the sun. For you did it secretly; but I will do this thing before all Israel, and before the sun.

Reading this chapter in David’s story can be sobering. The Torah is careful to display the vices of its heroes as well as their virtues. The story goes on to chronicle the devastating effects of David’s sin on his family and Jewish history.

The portrait of David’s dark side also has a powerful Didactic purpose. David’s sin is great, but the repentance modeled in his penitential Psalm 51 has comforted and inspired sinners for centuries. The Psalm is also a masterful poetic expression. Can you trace those figures of speech we discussed last week: Anaphora and Parallelism?

King David. Psalm 51, a prayer of repentance

Have mercy on me, O God,

according to your steadfast love;

according to your abundant mercy

blot out my transgressions.

Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity,

and cleanse me from my sin.

For I know my transgressions,

and my sin is ever before me. …

Indeed, I was born guilty,

a sinner when my mother conceived me.

You desire truth in the inward being;

therefore teach me wisdom in my heart.

Purge me with hyssop,[1] and I shall be clean;

wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.

Let me hear joy and gladness;

let the bones that you have crushed rejoice.

Hide your face from my sins,

and blot out all my iniquities.

Create in me a clean heart, O God,

and put a new and right spirit within me.

Do not cast me away from your presence,

and do not take your holy spirit from me.

Restore to me the joy of your salvation,

and sustain in me a willing spirit.

Then I will teach transgressors your ways,

and sinners will return to you. …

O Lord, open my lips,

and my mouth will declare your praise.

For you have no delight in sacrifice;

if I were to give a burnt offering, you would not be pleased.

The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.

[1] Hyssop: a plant used by the Israelites in purification rituals

Vital Questions

Context

Tales of hearts broken by love can be found in narrative traditions from all times and places. We have sampled two from a pair of cultural legacies that were of immense influence on the development of European culture and its art: the biblical and classical traditions that we will explore more closely in later chapters.

For now, let’s just notice that we have illustrated tales found in Ovid and the Bible with works by two masters from the Renaissance and Baroque eras of European art. At the time of their composition and today, viewers of the pieces by Bernini and Gentileschi need to know something of the story sources that the artists are dramatizing.

Content

This is a good moment to recognize that visual art often tells stories. Before the time of cinema, it was limited to static, unmoving images. Yet, in frozen moments of time, snapshots of action, great artists can capture multiple dimensions of story: setting, the flow of action, character intentions, and deep emotions.

Bernini’s figures are driven by passion, the Sun God’s desire and Daphne’s desperation. The figures rise in aspiration even as those emerging leaves initiate the nymph’s metamorphosis into the static life of a laurel tree. Similarly, Gentileschi shares with us the innocence of a chaste wife bathing while a dark menace looms overhead. Visual art does many things. Often, it tells stories.

Form

There is much to say of the formal effectiveness and elegance of these compositions. As we go along, we will be laying the groundwork for closer insights. For now, let’s simply notice Gentileschi’s handling of two elements of visual design: light and space. And let’s recognize their thematic significance.

Bathsheba and her handmaidens occupy the foreground. They are well lit from the upper right, bathing Bethsheba in a glow of innocence. The upper register of the composition is set back in the distance, David’s figure contracted by the distance. He and the walls of his palace are sunk in the gloom of shadow, a looming, barely perceived menace that will change the lives of Bathsheba, her husband, and the people of Israel.

References

Bernini, G. (1622-1624). Apollo and Daphne [Sculpture]. Rome: Galleria Borghese. https://www.collezionegalleriaborghese.it/en/opere/apollo-and-daphne

Gentileschi, A. (c 1640). David and Bathsheba [Painting]. Columbus OH: Museum of Art. https://5095.sydneyplus.com/final/Portal/Default.aspx?lang=en-US

Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version. (2021). Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-Revised-Standard-Version-Anglicised-NRSVA-Bible/#booklist

Ovid.. (8 CE). Daphne and Phoebus [Apollo]. Metamorphoses. I.452-524. Trans. Brookes More. Boston: Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Retrieved from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0028%3Abook%3D1%3Acard%3D452.

organically rooted in a culture’s heritage, a connected web of narratives, rituals, and art that illuminate origins, shape beliefs, map the world, and guide members of the culture in proper values, behavior and navigation of the environment

a meaningful sequencing of story events that builds suspense through conflict and rising tension culminating in a climactic resolution

a narrative’s central conflict driving the story’s mysteries and actions

a mythic tale which provides a framework for comprehending the development of some aspect of the heavens, the world, or human ways of living. Often presented as the birth of a people.

a quality of art that instructs its audience on information, ways of life, or social, moral, religious, or political principles

a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses: e.g. “I have a dream …” phrase repeated in Dr. Mar-tin Luther King’s speech, (8/28/1963).

a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms