3.2 The One Story: a Hero’s Journey

OK. I get it. This story seems kind of interesting. But it is over 4,000 years old. Do we really need to read it?

Granted, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a bit of a stretch. And this is our second sampling. We have already we explored the contextual link between the Sumerian tradition and the Mesopotamian roots of Hebrew culture. Let’s expand our vision and explore the roots that the tale shares with mythic narratives around the world.

Think about it. A master warrior who slays monsters and prevails over a transcendently powerful rival? A questing hero who endures long, perilous journeys? Haven’t we seen those movies before?

Joseph Campbell studied cultures in all times and places. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, (1968) Campbell traced in hundreds of tales, rituals, dreams and visions a universal narrative structure: the monomyth or “universal mythic formula of the adventure of the hero”:

The Hero’s Journey

a hero ventures forth from the world of the common day into a world of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive battle won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow men[1] (p. 30).

[1] Fellow men … and, presumably, women. Like many of the myths and rituals he analyzed, Campbell was by no means free of patriarchal bias.

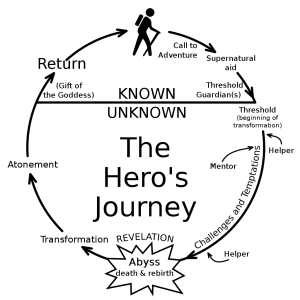

Campbell charts the universal story as a cyclical sojourn There and Back Again.[2] He identifies seventeen stages of the journey grouped in three phases:

- Departure: call to adventure, refusal of the call, crossing of the threshold into a dark, unknown, dangerous realm

- Initiation: road of trials, alliances with mentors and helpers, engagement with guardians, climactic abyss of conflict, death and rebirth, redemption and a precious gift

- Return: re-crossing of the threshold to the common world bearing a gift

|

| The Hero’s Journey. (N.D.). Graphic plot of Joseph Cambell’s theory of the archetype on which narratives are based. |

[2] There and Back Again: the subtitle of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

Campbell’s work was inspired by the psychoanalyst Carl Jung who saw in diverse cultures and the depths of the individual mind shared archetypes: common features and structures found in art, myth, folklore, literature, ritual, and dreams across times and cultures. Recently, the work of Jung and Campbell has been criticized and it is probably an exaggeration to say that all stories reduce to one. Yet his formulation aligns pretty well with many, many stories.

Indeed, Campbell has influenced generations of story tellers. Having read Campbell, George Lucas composed the original Star Wars (1977) as a myth for a time without myths. In 1992, Christopher Vogler, a Hollywood script writer, began circulating among writers of films, dramas, and fiction a summary of Campbell’s narrative template. Think of the scores of heroes in stories you have read or viewed who were called to an adventurous journey, underwent trials and temptations, and achieved wondrous triumphs before returning to normalcy.

Vital Questions

When we are wrapped up in the unfolding of a tale, we don’t reflect on much besides the fundamental question: what happens next? Yet our minds do often stray, don’t they? Watching an action hero movie, don’t you find yourself thinking about similar scenes and plot twists in other examples of the genre?

Thinking about story-telling, we do well to recognize the roots and branches of the ancient, global narrative tree that binds the human imagination together. Not all stories take heroes on journeys of adventure. But many do. It’s worth thinking about the structural web shared by ancient heroes like Achilles and Aeneas, Shakespearian heroes like Hamlet and Macbeth, and the heroes of our own day, Frodo Baggins, Harry Potter, Ironman, and Katniss Everdeen.

Context

The essence of a myth lies in its roots within the culture of origin. There is much to learn about Mesopotamian cultures and the myths that reflect their social, conceptual, and ideological frameworks.

But the point about archetypes is that they display dimensions shared by all cultures. Campbell’s idea of the monomyth is that all human cultures express themselves within a shared structural paradigm. The Hero’s Journey is rooted in every culture’s sense of home and away, us and them, safety and danger, the well-lit safety of the known and the simultaneously dreadful and intriguing realms of darkness.

Content

As a hero’s tale, Gilgamesh contains conventional ingredients. Heroes, allies, and monsters. Legendary battles, triumphs, and casualties, generally suffered by the hero’s companion, not the hero. It raises questions of value, competing ways of life, and mortality. And it reflects a people’s idea of glory.

Form

We will have more to say this week about narrative form. For now, Campbell’s notion of a cyclical journey is a good one to take with us. One way or another, heroes are called to go out in some sort of enterprise, to face dangers and conflicts, to be broken and approach despair, and then to win through to return home, often bringing a boon for themselves and for their people. It’s a venerable form that has held up for thousands of years and continues to enthrall readers and movie goers in our own day.

References

Campbell, J. (1968). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Epic of Gilgamesh. (c 2750 BCE). Kovacs, M. G, [Trans. Electronic Edition (I998). Academy of Ancient Texts, http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/

Hero’s Journey [Diagram]. (N.D.) Graphic plot of Joseph Cambell’s theory of the archetype on which narratives are based. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hero%27s_journey#

a single core narrative form that drives and shapes multiple story genres in all times and cultures. Campbell’s formula: “the universal mythic formula of the adventure of the hero” (1968, p. 21).

an immensely widespread narrative template in which a protagonist is called from ordinary life to an adventure in a challenging or dangerous realm and returns bearing a treasure of some kind