2.4 Epic Form

In the sections above, we have explored the formal techniques by which visual art composes its images and designs. Well, what of literary form?

You may be surprised to hear that ancient literature almost always begins in verse. Derived from oral traditions, it uses repetitive rhythms to aid bards in memorizing long texts and in maintaining the interest of an audience. Gilgamesh is composed in verse.

Of course, this verse is pretty different from modern ideas of poetry. And since we are dependent on translations, we can’t really look for Rhyme Scheme, Meter, or stanzaic forms.

So what does it mean to say that the text is written in verse? Well, the essence of poetry is always patterned rhythm. Do you recognize any pattern in this description of Enkidu, the great friend and rival of Gilgamesh?

He is the mightiest in the land,

his strength is as mighty as the meteorite(?) of Anu!

He continually goes over the mountains,

he continually jostles at the watering place with the animals,

he continually plants his feet opposite the watering place.

I was afraid, so I did not go up to him.

He filled in the pits that I had dug,

wrenched out my traps that I had spread,

released from my grasp the wild animals.

He does not let me make my rounds in the wilderness!”

We can recognize patterns in this passage even in translation from a written language that doesn’t necessarily share our ideas of sentences or syntax. The list of Enkidu’s acts of power use three common rhythmical patterns:

Anaphora: a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses

Catalogue: a rhetorical figure that rhythmically lists examples of a category to build intensity and emphasis

Parallelism: a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms

Gilgamesh abounds in catalogues like this one, many of them much longer. All combine to powerfully emphasize a characterization of actors in the story. These patterns are examples of figurative language:

Figure of Speech: a form of expression in which language departs from conventional norms in its patterns (Scheme) or meaning (Trope) for maximum rhetorical effect

Scheme: repeated patterns of expression that enhance the rhetorical effect of the text: e.g. alliteration, anaphora, catalogue, parallelism

The same figures we find in Gilgamesh have been used by poets and orators throughout the ages to make an impact on their audiences. Does your pastor excel at preaching? Pay attention to the rhythms of her expression. She almost certainly uses parallel rhythms, anaphora, and catalogues of reiteration to nail down her points.

Shamash and the Code of Hammurabi

Early Sumerian dominance was replaced by other Mesopotamian cultures in an ongoing cycle of dominance. A series of peoples shared Semitic language roots: Akkadians. Assyrians. Israelites. Despite their ethnic and linguistic differences, all of these peoples used cuneiform tablets and treasured the story of Gilgamesh.

A later version of Gilgamesh was recorded in Babylon,[1] the capital of two periods of imperial power. Hammurabi reined in the 1st Babylonian dynasty, long before the neo-Babylonian empire that conquered the Israelite kingdom of Judah in 605 BCE (relevant Hebrew scriptures: Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Lamentations and more).

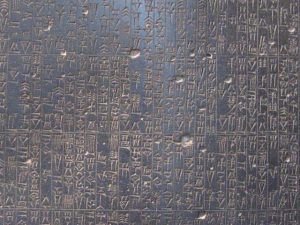

Hammurabi’s glory is commemorated in a basalt stele (or stela), a monument that affirms the king’s authority by portraying him in supplication before Shamash, a Babylonian god (see the detail). Steles were often set up by powerful rulers to affirm their authority, to delineate a realm’s boundaries of a realm, or to commemorate military triumph. But this one has a remarkable feature.

|

|

|

| Stele of Hammurabi (c 1792-1750 BCE) | Detail: Hammurabi and Shamash. | Detail: sample text. |

Mythic art generally provides guidance to behavior proper to members of a culture. Hammurabi’s stele pioneers a new level of explicit regulation of behavior. Below the image, one of the world’s first legal codes is inscribed in the basalt. The code prescribes behavior and specifies penalties for transgressions. Remarkably, a large proportion of the rules and regulations instruct farmers in proper maintenance of the irrigation canals that were crucial for Mesopotamian survival and prosperity.

[1] Babylon: today, the city of Hillel in Iraq.

Vital Questions:

So, what have we learned from our quick glance at Gilgamesh and Hammurabi? For one thing, we see that, in ancient art, visual and narrative art are closely intertwined. That linkage sets up our course interests in visual and literary art: prose and poetry.

Context

We know a great deal more about the context of the ancient Fertile Crescent than we did about Ice Age artists. Mesopotamian people throve by growing crops in the rich soil of the Tigris and Euphrates flood plain. Their abundance led to the opportunities of trade and the storage of surplus. To manage both, they developed the cuneiform system of writing on clay tablets. This accounting technology quickly evolved into literary recordings of their myths.

Content

Our encounter with Gilgamesh engaged two closely related arts concepts:

- Myth: a connected web of narratives and art that illuminate origins, shape beliefs, map the world, and guide members of the culture in proper values and behavior

- Epic: an extended narrative that celebrates heroic deeds exemplifying cultural values

As we will see next week, there is much to be said about narrative structure and heroes’ journeys. For now, we’ll notice two main dimensions of the Gilgamesh cultural myth:

- The communal ideal: Gilgamesh as the personification of civic achievement and the mediator between the people and the patron god, Inanna/Ishtar

- The spiritual journey: the epic’s probing of the human problem of mortality and the mysterious human inwardness that yearns to transcend life & death and connect with forces of creation

Form

We have noted that, like most ancient epics, Gilgamesh is composed in verse rhythms that draw on core figures of speech:

- Anaphora: a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses

- Figures of speech—Scheme: language which departs from conventional rhythms and patterns for maximum rhetorical effect

- Parallelism: a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms:

- Personification: a trope in which an idea, value, group or situation is represented in art as a person: e.g. Gilgamesh representing the community of Uruk

We noted that these patterns and figures are found in literature and oratory throughout the world. We will be meeting with them again!

References

Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh, fragment [Cuneiform tablet]. (15th C BCE). Jerusalem, IS: Israel Museum. https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/394521-0

Cuneiform Tablet. (19th C BCE). Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre, inv. 19658. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010124400

Epic of Gilgamesh. (c 2750 BCE). Kovacs, M. G, [Trans. Electronic Edition (I998). Academy of Ancient Texts, http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/

Gilgamesh and Enkidu Killing Humbaba, Guardian of the Cedar Forest [Terracotta relief]. (2nd millennium, BCE). Berlin, GE: Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. AN VA 7246. Amin, O. S. M. July 20, 2019). Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gilgamesh_and_Enkidu_slaying_Humbaba_at_the_Cedar_Forest._From_Iraq;_purchase._19th-17th_century_BCE._Vorderasiatisches_Museum,_Berlin.jpg

Lilith/Enanna/Ishtar [Relief]. (c 2025-1763 BCE.) Babylonian, Isin-Larsa period. London: UK: Norman Colville Collection, British Museum. RN 2003,0718.1. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_2003-0718-1

Ninsun, goddess mother of Gilgamesh [Fragmentary relief]. (c 2150 BCE). Neo-Sumerian period. Paris, FR. Musée du Louvre. AO 2761. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010151898

Stele of Hammurabi [Sculpture]. (c 1792-1750 BCE). Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre, SB 8; AS 6064. PEZARD ET POTTIER 8. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010174436

Shamash protecting King Nabu-apla-iddina {Clay relief]. (860 BCE). Shamash Temple. London, UK: British Museum. AN 91001. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1881-0701-3422

within a poem, a repeated pattern of sounds that end lines, defining stanzaic boundaries and shaping a poem’s themes. Designated for analysis by letters: e.g. a-b-a-b, in which a-lines and b-lines end in rhyming words.

a disciplined pattern of sound units throughout the lines of a poem. In English verse, meter is found in the number and a pattern of stressed and un-stressed syllables in a line