15.4 Global Spirituality

Evocation of a mysterious human inwardness …

Yearning to transcend life & death …

And connect with forces of creation

It is the nature of the spiritual to express itself in all times and places and in all the formal and stylistic variety of the human family. As Hopkins found spiritual enlightenment in the flight of a hawk, we can find it in works of art from any context.

And connect with Forces of Creation: Parietal Art

Remember those ghostly images of hands on the walls of deep caves in southern France? We could see them as attempts to depict a Representation of a human hand. But we learned that they occur deep in dark caves requiring a torturous, dangerous journey. Would outlines of hands really be worth such a trip?

|

|

|

| Chauvet: Negative Hand | Chauvet: Positive Hand | Chauvet: Hands and Dotted Half Circle |

But what if we follow see them as spiritual sojourns? Lewis-Williams believes that, in ancient rituals, “the rock wall” functioned as “a membrane between people and the subterranean spirit world” (2002, p. 217). Does the hair on the back of your neck stand up if you imagine shamans placing their hands on the living border of the spiritual realm? How about “negative” images embodying the passage the hands behind the membrane and into infinity?

Spirit in the Mist

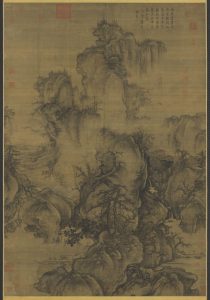

Let’s briefly return to the Genre of Chinese Landscape Painting. Can you remember and recognize the conventional features found in these compositions?

|

||

| Li Ch’eng. (10th C.) Solitary Temple amid Clearing Peaks. Ink on silk. | Xi Guo. (11th C CE). Early spring . Ink on Silk Scroll | Yin Tang. (c. 1510). Seeing Off a Guest on a Mountain Path. |

- Similar visual subjects: mountain, water, human habitation, minimized human figures

- Spatial zones: minimized foreground, looming middle distance, vanishing background

- Zones of negative space, cloudy, mysterious emptiness

“Vistas of the immaterial”: that’s what Van Thi Diepp (2017) called our attentions to, remember? Can you recognize the spiritual aspects of his reading of the tradition?

Chinese paintings depict landscapes merely to evoke spiritual exaltation. Minimized human figures, often monks or philosophers, perch on the sides of mountains looking into the heart of reality.

Church’s Vision of Creation

We turn to another of the artists we have already considered. Frederic Edwin Church, one of the artists associated with the Hudson River School, was inspired by landscapes that opened onto the sublime. As he traveled through the Americas, he found inspiration in awe-inspiring landscapes.

Church’s view of the Cotopaxi volcano certainly achieves the Sublime. But if we think spiritually of the yearning to transcend life & death and connect with forces of creation, can we not see creation and destruction, birth and death, a vision of Eden and perhaps of the end of the world?

|

|

|

| Cotopaxi. (1862). | Storm in the Mountains. (1857). | A Country Home. (1854). |

Unlike many paintings in the school of the Sublime, Storm in the Mountains turns its lens down to a scale that matches human experience: an isolated, twisted tree. But the tree is beset by howling storms that shriek nature’s lethal dangers. Yet A Country Home finds refuge from that storm. The home’s internal light reaches out to connect with the cosmic rays that shine through the rift in the clouds.

Whitman’s Spiritual Quest

Walt Whitman deserves far more time than we are giving him. But a pair of brief lyrics reminds us of the romantic spirit that inspired him.

Walt Whitman. (1882). Gliding o’er All

Through Nature, Time, and Space,

As a ship on the waters advancing,

The voyage of the soul—not life alone,

Death, many deaths I’ll sing.

Whitman was famous for his exalted view of himself. His great work is, after all, called Song of Myself. We can read this vision as a monstrous exercise in ego. But even if we do so, we need to understand that his notion of a “self” is a channel through which he knows and connects with everyone else and with the infinity outside himself. His mysterious human inwardness travels, “gliding o’er all, through all,” a soul voyaging outward, expanded by its embrace of everything.

Walt Whitman. (1867). When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

In “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” he channels Wordsworth’s “Expostulation and Reply,” looking for wisdom, not in dead books and mechanistic science, but in a moment of living communion between the night sky and a receptive human soul.

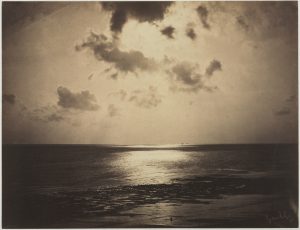

Spirit in the Lens

You will recall that, when first confronted by daguerreotypes, people were amazed by the automatically precise level of detail they offered. From the beginning, photography provided apparently inhuman accuracy in the depiction of the world one can see and touch.

Yet, from the beginning, artists with cameras found avenues to spiritual inspiration in their images.

|

|

| Gustave Le Gray. (1856). An Effect of the Sun, Normandy. Daguerreotype. | Willim Fox Talbot. (1843). The Open Door. Calotype. |

Gustave Le Gray’s daguerreotype finds the same sublime vision of a sea shore that Friedrich painted in his Monk by the Sea. And William Fox Tabot’s The Open Door uses Line, Form, and Composition to invite us into that mysterious human inwardness of the heart.

Stevens’ Restless Spirit

Wallace Stevens lived a wholly conventional life as a businessman, becoming the Vice President of the Hartford Insurance Company. He was also fascinated with Modern art and wrote poems that blast new spaces in one’s mind. Let’s try one.

Wallace Stevens. (19). The Snow Man

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Make any sense? Well, consider that Stevens focused with a terrible, prolonged intensity on the question, if our myths are being shattered by science and skepticism, how shall we look at the world? He concluded that one is not capable of an “objective” view of reality. Yet he kept trying to pull it off, finding in poem after poem that any rejection of one myth is immediately replaced by another.

In “The Snow Man,” Stevens attempts to imagine the “objective reality” of winter. As an experiment, he attempt to remove all human consciousness from the resulting vision. But wait, vision implies a viewer. OK, idea. No, Idea requires a mind. So he settles for a “mind of winter” which can somehow “regard” the realities of the cold “and not to think/of any misery.” Can you do it? Can you think of winter and strip away all memory of what cold feels like? If you live in Minnesota as I do, that’s tough.

But, says the poem, let’s imagine it. Let’s imagine a consciousness that is somehow able to strip away the impact of the world on the human being. What would that be? A snow man, the image of a person capable of perception but without any actual human experience? A “listener, who listens in the snow,/ And, nothing himself, beholds/ Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is”? Think about that.

Wallace Stevens was a spiritual man who had come to doubt the truth of spirit but spent a lifetime seeking a way to live with spiritual integrity in what was left of the world when spirit is removed.

Line, Form, Color: Rothko’s Spiritual Abstracts

Mark Rothko painted Abstracts. In his later years, he locked in one a formula horizontal bands of color bounded by organic Contour Lines. Can you think of anything less spiritual? Yet Rothko believed his compositions were profoundly spiritual. He even denied that he painted abstracts.

|

|

|

| Untitled (Black, Red over Black on Red). (1964). Oil on canvas. | No.5/No.22. (1964). Oil on canvas. | No. 14, 1960. (1960). Oil on canvas. |

So what is that brings people to tears in front of pure color and form? In part, surely we respond to the dense, drenching colors, often deep, organic reds. But there is something mesmerizing about those borders, never geometrical, always organic, invariably layered and bleeding. The WikiArt gloss for No. 5/No. 22 explores this visual ambivalence:

Do you feel something spiritual in your encounters with Rothko’s abstracts? Maybe not. Maybe one needs to get lost in one for a while. To begin to feel the sense of permeable borders and membranes opening us to the same spiritual dimension touched by those artists in the dark of southern France thousands of years ago. The fact is, most, perhaps all of life is spiritual:

An evocation of a mysterious human inwardness …

Yearning to transcend life & death …

And connect with forces of creation

References

Chauvet—Media Library [Photographic Gallery]. (2015). The Chauvet-Pont d’Arc Cave. French Ministry of Culture and Communication https://archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet/en/close-cave-painting

Church, F. E. (1854). A Country Home. [Painting]. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/frederic-edwin-church/country-home-1854

Church, Frederic Edwin. (1862). Cotopaxi [Painting]. Detroit, MI: Detroit Institute of Arts. https://dia.org/collection/cotopaxi-37907

Church, F. E. (1854). Storm in the Mountains. [Painting]. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. AN 1969.52 https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1969.52

Church, F. E. (1857). Niagara. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art. Accession Number 76.15. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18119918

Diep, V. T. (2017). The landscape of the void: Truth and magic in Chinese landscape painting. Journal of Visual Art Practice, 16(1), 77-86.

https://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=121504878&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Gardner, A. (1862). Home of a rebel sharpshooter, Gettysburg [Daguerreotype]. In Gardner’s Photo-graphic Sketchbook of the War. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283195

Guo, X. (11th C CE). Early spring [Painting]. Taipei, Taiwan: National Palace Museum. https://www.npm.gov.tw/Exhibition-Content.aspx?sno=04011674&l=2#lg=lg0&slide=1

Le Gray, Gustave. (1856). An Effect of the Sun, Normandy [Photograph]. Cleveland, OH: The Cleveland Museum of Art. AN 1987.54. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1987.54

Lewis-Williams, D. (2002). The Mind in the Cave. London: Thames & Hudson.

Li, Ch’eng. (10th century). Solitary temple amid clearing peaks [Painting]. Kansas City, MO: Nelson Atkins Museum of Art. https://art.nelson-atkins.org/people/8540/li-cheng/objects

Rothko, Mark [Article]. (2015). Chilvers, I., & Glaves-Smith, J. (Ed.s). A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191792229.001.0001/acref-9780191792229-e-2338

Rothko, M. (1964). No.5/No.22 [Painting] New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/80566

Rothko, M. (1960) No. 14, 1960 [Painting]. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/97.524/

Rothko, M. (1964). Untitled (Black, Red over Black on Red) [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou. Accession Number AM 2007-126. https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/ressources/oeuvre/cajrkgR

Stevens, W. (1921. The Snow Man [Poem] in Harmonium. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45235/the-snow-man-56d224a6d4e90

Talbot, W. H. F. (1843). The open door. [Calotype Photograph]. Plate VI. The Pencil of Nature. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Object. 2005.100.498. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283068

Tang, Y. (ca. 1505-1510). Seeing off a guest on a mountain path [Painting]. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum. https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/23342

Whitman, W. (1882). Gliding o’er all, through all [Poem]. In Leaves of Grass. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56337/gliding-oer-all

Whitman, W. (1867). When I heard the learn’d astronomer [Poem]. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45479/when-i-heard-the-learnd-astronomer

Whitman, W. (1882). Gliding o’er all, through all [Poem]. In Leaves of Grass. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56337/gliding-oer-all

Whitman, W. (1867). When I heard the learn’d astronomer [Poem]. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45479/when-i-heard-the-learnd-astronomer

an aesthetic effect in art in which the viewer or reader experiences awe, even fear in a representation that (safely!) carries the imagination into danger, terror, darkness, solitude, or infinity

visual art that makes little or no effort to represent any recognizable subject and appeals to purely aesthetic sensibilities

the boundary line that defines a shape or form in a visual composition. A contour line can be directly drawn or achieved merely through contrast be-tween the colors of the subject and the background.