15.3 Neo-Christian Romanticism

We looked at Romanticism in Chapter 9. If you think about it, Romanticism is essentially a spiritual perspective: looking within to find wisdom and connect with the forces of creation and infinity.

In 19th Century Europe and the Americas, Romanticism provided one way to deal with the fracturing of the Christian consensus. Artists drew on the Christian traditions that shaped their world and its artistic traditions. But many found themselves restlessly re-inventing those traditions to express unconventional visions.

Blake’s Neo-Christian Vision

The most radical of English Romantic voices, William Blake formulated his personal vision by drawing on an intimate knowledge of Christian tradition, especially the Bible and the poetry of John Milton, author of two great Christian epics, Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained (if only we had time!). His Milton narrates his own spiritual turmoil in an epic form invoking Milton, Virgil, and Homer.

In the Frontispiece of Europe, a Prophecy, Blake composes an unforgettable image of Jehovah that can be seen as a conventional homage to the Judeo-Christian God. But notice the geometrical angle projected by those split, creating fingers. Blake was fascinated by physicist Isaac Newton’s mathematical model of gravity and the motions of the stars. His image of Jehovah emphasizes the mathematical precision of creation.

|

| William Blake. (1794). The Ancient of Days. Frontispiece. Europe, a Prophecy. Relief etching with watercolor. |

But Blake was also appalled by what he saw as an unhealthy, unbalanced obsession with Reason that suppressed the imagination and other human energies. This Creator’s hand may measure the heavens with a surveyor’s calipers, but the light penetrating cosmic gloom is fired by passion and imagination.

Blake’s vision is perennially driven by a profound sense of the dualities that make up life and wisdom. His The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790) seeks spiritual vision where many mystical visionaries have sought it, in the dynamic tension that unites opposites

Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence.

From these contraries spring what the religious call Good & Evil. Good is the passive that obeys Reason. Evil is the active springing from Energy.

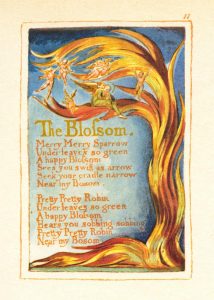

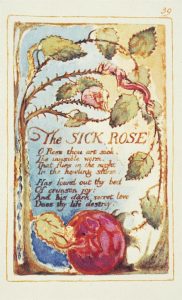

We have already sampled Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794). Let’s sample another pair of short lyrics from the collection. “The Blossom” cheerily celebrates God’s creation. “The Sick Rose” worries at the sickness at Nature’s core: death.

|

|

| The Blossom (1794). | The Sick Rose. (1794). |

| MERRY, merry sparrow! Under leaves so green, A happy blossom Sees you, swift as arrow, Seek your cradle narrow Near my bosom. Pretty, pretty robin! Under leaves so green, A happy blossom Hears you sobbing, sobbing, Pretty, pretty robin, Near my bosom. |

O ROSE, thou art sick! The invisible worm, That flies in the night, In the howling storm, Has found out thy bed Of crimson joy; And his dark secret love Does thy life destroy. |

Christians may be a bit uncomfortable with Blake’s bold, dissenting models of faith. We can, however, approach Blake as an artist imaging and voicing universal spiritual themes of life and death, creation and destruction, freedom and restraint.

Friedrich’s Sublime Faith

|

| The Cross in the Mountains. (1808). Oil on canvas. |

We have viewed Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings as explorations of the sublime. We can also view them as expressions of a Christian imagination that is struggling to deal with a Christian culture that is beginning to overflow the boundaries of orthodoxy. His painting was intended to be placed in a chapel, and its spiritual dimensions are obvious. But the Christian Iconography is minimalized. And yet, it is still there.

|

|

| Abbey amidst Oak Trees. Oil on canvas. | Winter Landscape (1811). Oil on canvas. |

On one level, Friedrich’s Abbey amidst Oak Trees is a celebration of Europe’s architectural heritage, a major enthusiasm at the time. Yet the Abbey is in ruins. Does it betoken a broken church? Or a persisting faith?

Winter landscape places a cripple, recumbent in the snow, who has discarded his crutches before a crucifix. In the deep distance, a ghostly cathedral points upward. We feel the chill of the winter of faith but are moved by the faithfulness of a crippled supplicant finding grace before a private crucifix.

|

| Monk by the Sea. (1809). Oil on canvas |

We return to Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea. The title provides this miniscule figure with a spiritualized identity. Yet the image displays few specific features and the figure could be any human being standing before the vastness of a world that dwarfs us while inspiring our hearts to soar:

Evocation of a mysterious human inwardness …

Yearning to transcend life & death …

And connect with forces of creation

William Butler Yeats: a Spiritual Sojourn

Have you ever struggled with your faith, vacillating between doubt and conviction? If so, you may resonate with William Butler Yeats’ poems. In his early years, he toyed with ancient Celtic myths. As he aged, traumatized by the horrors of World War I, Yeats restlessly sought peace, developing a private mythology in which human experience cycles between opposite poles. In Week 2, we read one of his Crazy Jane poems, a series of reflections blending bitterness with hopeful wonder. Here is another from the series.

William Butler Yeats. (1932) “Crazy Jane on God”

That lover of a night

Came when he would,

Went in the dawning light

Whether I would or no;

Men come, men go;

All things remain in God.

I had wild Jack for a lover;

Though like a road

That men pass over

My body makes no moan

But sings on:

All things remain in God.

Banners choke the sky;

Men-at-arms tread;

Armored horses neigh

In the narrow pass:

All things remain in God.

Before their eyes a house

That from childhood stood

Uninhabited, ruinous,

Suddenly lit up

From door to top:

All things remain in God.

In “Crazy Jane on God,” Yeats evokes the age-old destiny of women who have known warriors who rape and “wild Jacks” who love passionately before abandoning them. In age, Jane has passed beyond the vulnerability of passion and impassively beholds the eternal cycle of war. Yet, in each Stanza, she muses on a timeless, implacable truth, “All things remain in God.”

But the poem closes on a startling moment of spiritual grace, a miraculous memory of a sudden eruption of unearthly light in a ruined house. Though he wandered far from the Christianity of his youth, Yeats treasured moments. In his great poem “Vacillation” (1932), he probes through VIII far-ranging stanzas his spiritual ambiguities, doubts, and convictions. In stanza IV he recalls another magical moment of grace, this one remembered from an afternoon in a book shop.

William Butler Yeats (1932). From “Vacillation.”

IV

My fiftieth year had come and gone,

I sat, a solitary man,

In a crowded London shop,

An open book and empty cup

On the marble table-top.

While on the shop and street I gazed

My body of a sudden blazed;

And twenty minutes more or less

It seemed, so great my happiness,

That I was blessed and could bless. …

Some Christians may struggle with Yeats’ decision to turn away from the Church of his baptism. Yet spiritually sensitive people of all perspectives may empathize with the honesty of his struggle to make an authentic choice. Many people, whatever their perspective, can relate to his cycles of faith and doubt and treasure remembered moments of spiritual grace resembling that of Yeats:

And twenty minutes more or less

It seemed, so great my happiness,

That I was blessed and could bless.

References

Blake, William. (1794). The Ancient of Days. Frontispiece. Europe, a Prophecy (1794) [Relief etching with watercolor]. Private Collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/william-blake/the-ancient-of-days-1794

Blake, William. (1789 to 1794). The Blossom. Songs of Innocence: Plate 11 [Etching]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/347908

Blake, W. (1789). The Blossom [Poem]. Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. Poetry Lovers Page https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43682/the-sick-rose

Blake, William. (1789 to 1794). The Sick Rose. Songs of Innocence and of Experience. plate 39. [Etching]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/347973

Blake, W. (1789 to 1794). The Sick Rose [Poem]. In Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience.. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryloverspage.com/poets/blake/blossom.html

Blake, William. (1789 to 1794). Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Plate 2, Combined Title Page [Relief etching with watercolor]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/892559

Blake, William. (c. 1793). The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Frontispiece. [Relief etching with watercolor]. William Blake Archive. https://www.blakearchive.org/copy/mhh.a?descId=mhh.a.illbk.01

Blake, William [Article]. (2012). In D. Birch & K. Hooper, (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-842.

Friedrich, C. D. (1809-10). Abbey Amidst Oak Trees [Abtei im Eichwald]. Berlin, GE: Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. AAN NG 8/85. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caspar-david-friedrich/the-abbey-in-the-oakwood

Friedrich, C. D. (1808). The Cross in the Mountains [Painting]. Dresden, GE: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caspar-david-friedrich/cross-in-the-mountains-1806

Friedrich, C. D. (1809). Monk by the Sea [Painting]. Berlin, Germany: Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. NA 9/85. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caspar-david-friedrich/the-monk-by-the-sea-1810

Friedrich, C. D. (1818). Wanderer Above the Sea of Mist. [Painting]. Hamburg GE: Kunsthalle Hamburg. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caspar-david-friedrich/the-wanderer-above-the-sea-of-fog

Friedrich, C. D. (1811). Winter Landscape. [Painting]. London: National Gallery. AN NG6517. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/caspar-david-friedrich-winter-landscape

Mee, J. (1999). “Blake, William.” [Article]. In I. McCalman, J. Mee, G. Russell, C. Tuite, K. Fullagar, and P. Hardy (Ed.s), An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199245437.001.0001/acref-9780199245437-e-62.

Songs of Innocence [Article]. (2012). Birch, D., and Hooper, K. (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-7078.

Yeats, W. B. (1932). “Crazy Jane on God.” In Words for Music, Perhaps. https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/crazy-jane-on-the-day-of-judgment/#content.

Yeats, W. B. (1933). “Vacillation.” In The Winding Stair. http://www.csun.edu/~hceng029/yeats/yeatspoems/Vacillation.

A) a reaction against Neo-Classical Reason that seeks to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom. B) as an aesthetic, a rejection of strict artistic rules and convention in favor of organic form and innovation. C) often, advocacy for folk traditions that have been despised by classical elites

committed to the late 18th and 19th Century reaction against Neo-Classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom.

a division of within a poem that functions as does a prose paragraph and organizes the poem’s themes. Stanzas are labelled according to their number of lines and are often, but not always, defined by rhyme schemes.