14.6 Art and Harlem

The phrase Harlem Renaissance normally invokes the literary achievements of poets and novelists. But, as is suggested by the work of Aaron Douglas, the cultural successes of the time extend to visual artists as well. While they were often based elsewhere, their achievements fit into the general scope of the movement.

Between 1922 and 1967, the Harmon Foundation, a philanthropic enterprise sponsored by a wealthy real estate developer, sponsored African American artists with annual awards and touring shows that shared Black artistic achievement with visitors to art museums across the nation. The era of the Harlem Renaissance showcased art as well as literature.

Delving for Roots: Meta Warrick Fuller

Daughter of middle class African American parents, 16-year-old Meta Warrick Fuller showed enough early promise to have her work displayed in Chicago’s World’s Columbia Exposition in 1893. She later studied sculpture in Paris, working with Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel (Fuller, Meta Warrick, 2005).

Warrick Fuller’s style and technique reflect the Romantic influence of Rodin and Claudel. But her subject matter seeks the African heritage of her people. She met W. E. B. Du Bois in 1900 and was deeply influenced by his vision for elevating the cultural possibilities for Black people. She produced Spirit of Emancipation “at the invitation of Du Bois to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation’s fiftieth anniversary in New York City in 1913,” an elevating composition that survives only as a plaster model in Boston’s Museum of the National Center of African American Artists (Fuller, Meta Warrick, 2005).

|

|

|

| Spirit of Emancipation. (1913). Bronze Sculpture. | Ethiopia Awakening. (1914). Bronze Sculpture. | Talking Skull. (1939). Bronze Sculpture. |

Warrick Fuller’s later works continue to seek the African roots of her heritage. Ethiopia Awakening personifies the struggle for African peoples to emerge from the oppression of European colonization. The reference to Ethiopia honors the only African nation that was never colonized. In Talking Skull, a yearning figure kneels on the earth that encompasses the bones of the ancestors, reaching out for communion with a representative skull.

The Multiple Visions of Archibald Motley

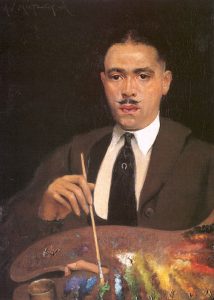

|

| Self Portrait. (1920). Oil on canvas. |

In the last section, we explored Langston’s Hughes’ frustration at the idea that, to earn the respect of the social mainstream, Black writers should strive to erase the authentic voices of his people. For Archibald Motley, Hughes’ “Racial Mountain” posed complex challenges regarding African American image.

In his teens and twenties, Motley studied painting at the Chicago Institute of Art and then, on a Guggenheim fellowship, in Paris. Can you see the Conventional Illusionist style and technique in his portraits?

|

|

|

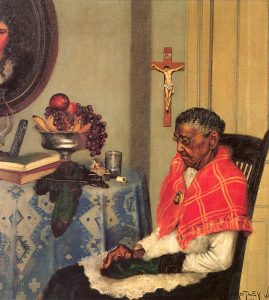

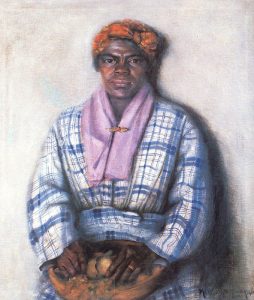

| Mending Socks. (1924). Oil on canvas. | Octaroon Girl. (1925). Oil on canvas. | Mammy. (1924). Oil on canvas. |

But notice something else in those portraits. Born in Louisiana, Motley had a firm understanding of the multiple ethnic heritages that comprised the African American community. “Black” people actually exhibited a wide array of skin tones: “His interest in documenting these differences in portraiture refuted the concept of a monolithic blackness and … provided a ‘visual rebuttal’ to the negative stereotypes of African American frequently found in popular culture during this period” (Mooney, 2011). The term colorism refers to a tragic social hierarchy within the African American community based on the dark or lightness of skin. Motley tackled those tonal differences, although his bravery resulted in controversy and disapproval from some Black writers and scholars.

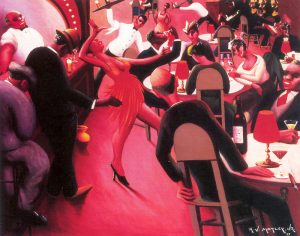

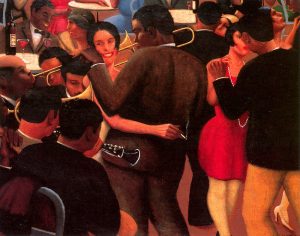

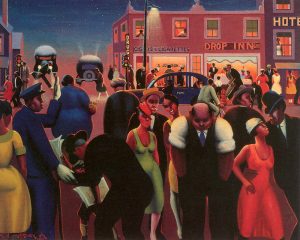

Mooney (2011) holds that Motley “eschewed the demand for art as propaganda, repeatedly stating that he intended to depict African Americans ‘honestly,’ including the humor and pathos black life. He painted numerous scenes of Black social life, often using a Stylized technique that, for some, at times came uncomfortably close to trading on negative stereotypes of the day.

|

|

|

| Saturday Night Scene. (1924). Oil on canvas. | Blues. (1929). Oil on canvas. | Black Belt. (1934). Oil on canvas. |

The tensions and conflicts of Black life in Motley’s work are far too complex for us to work out here. We can notice that, like Hughes and Hurston, Motley struggled with difficult-to-reconcile commitments to authenticity, Style, and the challenge of testifying to the respect that Black culture deserves.

Vital Questions

Context

Few moments in cultural history pulse with the energy and revelation of the Harlem Renaissance. This was a time of unprecedented cultural achievement for Black musicians, writers, and artists. It was also a bitter time in which the ceiling was lifted slightly, but slammed down again by a mainstream culture that didn’t really care about anything other than jazz music and dance. Even musicians who seemed to achieve great renown were allowed only limited freedom. Harlem nightclubs such as the Cotton Club showcased Black performers but did not allow African American to sit down to a table as customers. For every step forward, it seemed, the members of the New Negro movement were pushed two steps back.

Content

In The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. Du Bois tries to explain the African American’s sense of “double consciousness”:

Even when they were finding sponsorship and approval, Black writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance felt divided responsibilities: to represent their people’s authentic selves but also to earn the respect of a culture that demanded a different image, a different identity. Douglas. Cullen. McKay. Hughes. Warrick Fuller. Motley. These artists always faced the challenge of presenting a divided content, their people’s experience and an elevated social identity to which they could aspire.

Form

The double consciousness testified to by Du Bois tended to lead to a divided Style. Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God alternates between an “elegant” literary fluency and that magnificent voice that bubbled up among the wits playin’ de dozens on the front porch. Hughes moved back and forth between the voice of the litterateur and that of the Blues man. Motley insisted on painting the diverse skin tones of his people and adjusting his style to the boisterous night life of the cities. To meet the challenge of these artists, we need to cultivate a double consciousness of our own.

References

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The Souls of Black Folks: Essays and Sketches. Chicago, IL: McClurg & Co. Project Gutenberg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Souls_of_Black_Folk

Fuller, Meta Vaux Warrick [Article]. (2005). Hine, D. L. [Ed.]. Black Women in America. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mooney, A. M. (2011). Motley, Archibald J., Jr. [Article]. Marter, J. [Ed.] The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195335798.001.0001/acref-9780195335798-e-1407

Motley, A. (1934). Black Belt [Painting]. Arthistory Project. https://www.arthistoryproject.com/site/assets/files/33228/archibald_motley-black_belt-1934-trivium-art-history-1.webp

Motley, A. (1929). Blues, 1929 [Painting]. Chicago, IL: Chicago History Museum. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/archibald-motley/blues-1929

Motley, A. (1924). Mammy [Painting]. Wikiart https://uploads1.wikiart.org/00230/images/archibald-motley/mammy.jpg!Large.jpg

Motley, A. (1924). Mending Socks [Painting]. Chapel Hill, NC: Ackland Art Museum (University of North Carolina), Chapel Hill, NC. https://www.wikiart.org/en/archibald-motley/mending-socks-1924

Motley, A. (1920). Nightlife [Painting]. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago. AN 1992.89. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/117266/nightlife

Motley, A. (1925). The Octaroon Girl [Painting]. New York NY: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. https://michaelrosenfeldart.com/artists/archibald-j-motley-jr-1891-1981

Motley, A. (1948). Portrait of a Cultured Lady [Painting]. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/archibald-motley/portrait-of-a-cultured-lady-1948

Motley, A. (1924). Saturday Night Scene [Painting]. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/archibald-motley/saturday-night-1935

Motley, A. (1920). Self Portrait [Painting]. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago. https://www.artic.edu/artists/42445/archibald-john-motley-jr

Warrick Fuller, M. (1914). Ethiopia Awakening [Sculpture]. New York, NY: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/25b37950-c6f4-012f-ae5e-58d385a7bc34#/?uuid=671040d4-2bfa-0930-e040-e00a1806450c

Warrick Fuller, M. (1913). Spirit of Emancipation [Sculpture]. Boston, MA: Harriet Tubman Park. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/meta-vaux-warrick-fuller/emancipation-1913

Warrick Fuller, M. (1939). Talking Skull [Sculpture]. Boston, MA: Museum of African American History. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/meta-vaux-warrick-fuller/talking-skull-1939

a representational technique that depicts the idea of a visual subject through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis

a consistent pattern of choices regarding form and technique that comprise an identity for an artistic tradition, movement, or individual vision