14.4 Academic Harlem

What do the words “1920s Harlem” make you think of? Music, right? The jazz greats we just peeked at? Through radio and the recording industry, music provided African American with an unprecedented opportunity to find fame and influence by expressing their culture.

Unfortunately, jazz and blues music did little to challenge the stereotypical myth of African American culture as being primitive, inferior to the American mainstream. Jazz was often referred to as “Jungle Music,” evidence of the atavistic instincts of less than fully human beings.

At the same time, however, Black scholars and writers were pioneering a different kind of cultural enterprise. The “New Negro Movement, which took place in the 1920s, … is better known as a literary movement, … invoking a rebirth of African American creativity” (Leininger-Miller, T., 2011).

Today, the New Negro Movement is known as the Harlem Renaissance. It was deeply rooted not just in the comparative prosperity of Black people living in Harlem, but also in education. Harlem stretches just north from Columbia University. New York, the nation’s publishing capital, drew on the talents of people educated in traditionally Black colleges and universities. Writers, painters and sculptors formed a community in Harlem. Powerful literary voices challenged the stereotype of African American inferiority.

DuBois: The Talented Tenth

|

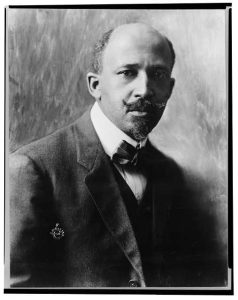

| Battey, C. M. (May 31, 1919.) Portrait of W. E. B. Dubois. Photographic Print. |

One of the most powerful of those voices belonged to W. E. B. Du Bois. Du Bois was educated at Fisk and Harvard Universities, earning a Ph.D. in sociology on the Cambridge campus. His 1903 book The Souls of Black Folks offered the world’s first authentic, respectful exploration of African American culture. In Harlem, he edited Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and supported the writers and artists who congregated there.

As an educator, Du Bois was frustrated by the restricted, Booker T. Washington model of instruction commonly available to African American youth. Schools such as the Tuskegee Institute offered training designed to prepare Black youth for the service jobs available to an underclass. Du Bois knew that his people were capable of more than that. In 1903, Du Bois published an essay on African American education that raised the focus to intellectually gifted youth, what he called the Talented Tenth:

W. E. B. Du Bois. (1903). from “The Talented Tenth” essay.

In the essay, Du Bois argues that the more talented of Black youth are capable of the same exalted levels of cultural achievement as is anyone else. This apparently straightforward notion clashed with everything that America thought it knew about people whose bondage had for centuries been justified by assumptions of their inferiority. To support his belief in Black capabilities, Du Bois sponsored writers and artists who were gathering in Harlem. He loved to tell the story of a poem posted for discussion without the writer’s name in a graduate literary seminar at a major university. “Who is this?” asked the professor. The students guessed many of the foremost names in English poetry. The author, Du Bois was proud to affirm, was a Black man.

Countee Cullen

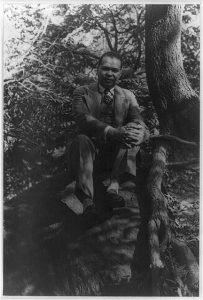

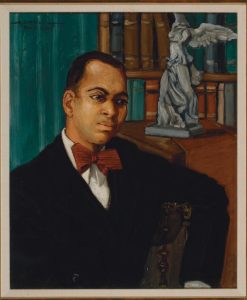

Countee Cullen was a literary scholar who earned a Master’s degree at Harvard in 1926. His great literary love was for the great English tradition which had culminated in Romantic and Victorian poetry. He was an accomplished poet who published ironic verse displaying the subtle, elegant features of his British models.

|

|

| Carl van Vechten. (1941). Countee Cullen. | Winold Reiss. (1925). Countee Cullen. Pen and ink.. |

He was also an African American at a time when mainstream society thought it knew that advanced studies were beyond the capabilities of Black people. With the support of Du Bois and the scholar James Weldon Johnson, Cullen was able to find publication despite the crushing obstacles faced by Black artists.

Countee Cullen. (1925). “Yet Do I Marvel”

I doubt not God is good, well-meaning, kind

And did He stoop to quibble could tell why

The little buried mole continues blind,

Why flesh that mirrors Him[1] must someday die,

Make plain the reason tortured Tantalus[2]

Is baited by the fickle fruit, declare

If merely brute caprice[3] dooms Sisyphus[4]

To struggle up a never-ending stair.

Inscrutable His ways are, and immune

To catechism[5] by a mind too strewn

With petty cares to slightly understand

What awful brain compels His awful hand.

Yet do I marvel at this curious thing:

To make a poet black, and bid him sing!

[1] Flesh that mirrors Him: a reference to the biblical idea that humans are made in the image of God

[2] Tantalus: a character in Greek mythology punished in Hades by being forced to stand forever in a pool of water with fruit above his head, both of which perpetually shrink away whenever he reaches for them.

[3] Brute caprice: i.e. unreasoning accident

[4] Sisyphus: another character punished by endless frustration. Sisyphus was forced to push a large rock up a hill, only to have it perpetually fall back down just before he could reach the summit.

[5] Immune to catechism: i.e. inaccessible to questioning

This bitterly ironic Sonnet testifies to Cullen’s skill and erudition. He is as classically learned and prepared as any other poet. But the sonnet testifies to the near impossibility of a Black writer thriving in America.

We’ve looked at the Conventional structure of the Shakespearian Sonnet. That killer final Couplet: can you see how it reverses the previous Stanzas? “I doubt not …” the poem begins, expressing a willingness to believe the most challenging realities tolerated by God. But there is one “curious thing” that he cannot see how to understand or accept: how can a Black man, born to be a poet, be expected to sing?

“For a Lady I Know”

She even thinks that up in heaven

Her class lies late and snores

While poor black cherubs rise at seven

To do celestial chores.

“A Lady I know.” Let’s unpack those four words. In Cullen’s world, “a lady” would be an aristocratic woman of wealth and prestige. She would not be Black. The fact that he, a Black man, would be allowed to “know” her socially would be a small miracle. The Harlem Renaissance was sponsored by a small cohort of sophisticated, avant-garde, elite New Yorkers willing to “know” Black artists and writers at cocktail parties in their homes. In the wider American world of the time, a white society matron hosting a Black man in her home would be unthinkable.

But the poem does not stop after the title. Cullen shares with us a condensation of this apparently liberal woman’s thought process. “She even thinks …” what? That the African American’s subservient role is so deeply rooted in the universe that “poor black cherubs” could be counted on to serve her even in heaven. That is Irony.

Let’s look at one more instance of Cullen’s devastating irony. I’ll let you handle this one for yourself.

Incident (1925)

(For Eric Walrond)

Once riding in old Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-filled with glee,

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me.

Now I was eight and very small,

And he was no whit bigger,

And so I smiled, but he poked out

His tongue, and called me, “Nigger.”

I saw the whole of Baltimore

From May until December;

Of all the things that happened there

That’s all that I remember.

Claude McCay

Like Countee Cullen, Claude McKay reflected the stylistic and structural traditions of English verse in his poetry. Unlike Cullen, McKay was born in Jamaica. Emigrating to New York in his teens, he felt frustrated, as did many Caribbean immigrants, by the degree to which Black people born and socialized in America tended to simply accept their lot in a profoundly oppressive society.

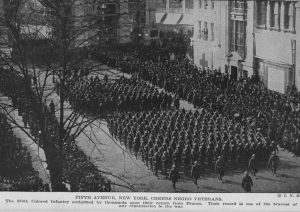

In 1919, American soldiers returned from World War I. A massive parade on New York’s fashionable 5th Avenue celebrated the sterling combat record of Harlem’s own 359th Regiment.

|

|

|

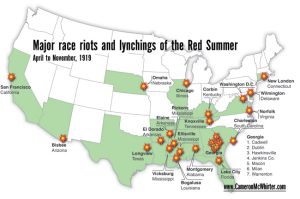

| Kelly Miller. (1919). 5th Avenue, New York, cheers The 369th Colored Infantry. | Jun Fujita. (July 1919). White men stone a Black man, 1919 race riot, Chicago. | Cameron McWhirter,. (2012). Map of Major Race Riots and Lynchings, 1919. |

Then things turned sour. As is true in most post-war contexts, the American economy faltered at the sudden drop in demand for military goods. A deeply racialized society turned its frustrations onto Black people, blaming them for the crisis. During the so-called Red Summer of 1919, race riots exploded in cities across America. White mobs attacked Black people, destroyed buildings, and killed the innocent. In Chicago, a lethal riot was triggered by Black youths swimming in the wrong part of Lake Michigan. In Omaha, Nebraska, Black neighborhoods were actually bombed from low flying airplanes.

In his sonnet responding to the crisis, Claude McKay challenged the idea of passively accepting the outpouring of hate. I invite you to bring the skills you are developing to bear on this outcry. Sonnet structure. Rhyme Scheme. Metaphor. Simile. How does McKay so powerfully express his anguish and proud despair?

If We Must Die. (1919)

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursèd lot.

If we must die, O let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

References

Allen, J. L. (c 1930). Claude McKay [Photograph]. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mackey.jpg

Battey, C. M. (May 31, 1919.) Portrait of W. E. B. Dubois. Photographic Print. Washington D. C. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Digital ID: cph 3a53178. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003681451/

Cullen, C. (1927). For a Lady I Know [Poem]. In Caroling Dusk. New York: Harper & Brothers. All Poetry https://allpoetry.com/For-A-Lady-I-Know

Cullen, C. (1925). Incident. Color. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42618/incident-56d2213a45f36

Cullen, C. (1925). Yet Do I Marvel. Color. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42611/yet-do-i-marvel

Douglas, A. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life: Panel 3: From Slavery Through Reconstruction [Painting]. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003019831

Douglas, Aaron. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life: Panel 4: Song of the Towers. Oil on canvas. New York, NY: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003152087

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The Talented Tenth. The Negro Problem: a Series of Articles by Representative Negroes of Today. (New York). Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Law Library https://librarycollections.law.umn.edu/documents/darrow/Talented_Tenth.pdf

Fujita, Jun. (July 1919). Two white men stone an African American man during the 1919 race riot in Chicago [Photograph.] Chicago IL: Chicago History Museum: ICHi-022430. https://www.chicagohistory.org/chi1919/

Johnston, Sir H. H. (1910). Portrait of W. E. B. Du Bois [Photograph]. New York NY: The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 1229011 https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-8d7b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Leininger-Miller, T. (2011). Harlem Renaissance. [Article]. Marter, J. (Ed.), The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195335798.001.0001/acref-9780195335798-e-861.

McKay, C. (July 1919). If we must die. Liberator. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44694/if-we-must-die

Miller, Kelly. (1919). Fifth Avenue, New York, cheers Negro Veterans; The 369th Colored Infantry [Photograph]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image 1206640 https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-7baa-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

McWhirter, Cameron. (2012). Map of Major Race Riots and Lynchings, 1919 [Illustration]. In Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. St. Martin’s Griffin. Evanston IL: Evanston Public Library. https://www.epl.org/an-interview-with-cameron-mcwhirter/

Reiss, W. (1925). Countee Cullen [Drawing]. New York NY: The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 1229296 https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-9592-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

committed to the late 18th and 19th Century reaction against Neo-Classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom.

a 14-line lyric poem that explores a theme in stanzas with a thematic turn either between lines 8 and 9 (Petrarchan/Italian Sonnet) or between lines 12 and 13 (Shakespearian/English Sonnet).

(English) a 14-line poem arranged in 4 stanzas that rhyme ab-ab/cdcd/efef/gg. The 1st 3 stanzas develop a theme or problem. A thematic turn between lines 12 and 13 sets up a powerfully compact couplet that packs the force of a punch line.

a verse stanza of 2 lines, often ending in a rhyme

a division of within a poem that functions as does a prose paragraph and organizes the poem’s themes. Stanzas are labelled according to their number of lines and are often, but not always, defined by rhyme schemes.

an often wryly humorous, indirect mode of communication that asks the reader to compare what is said with some known or signified reference. Frequently used to puncture false pretentions, especially of the social elite. E.g. a standup comedian who relies on the audience to draw on what it knows about a celebrity to get the joke.

within a poem, a repeated pattern of sounds that end lines, defining stanzaic boundaries and shaping a poem’s themes. Designated for analysis by letters: e.g. a-b-a-b, in which a-lines and b-lines end in rhyming words.

a trope which denotes a “non-literal” thing, idea, or action to characterize a “real” term. E.g. “All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players” (William Shakespeare, As You Like It, 1599).

a trope that explicitly compares a “literal” with a “figurative” term, usually indicating the comparison with like or as: e.g. “I wandered lonely as a cloud” (William Wordsworth, “Daffodils” (1807).