14.3 Take the A Train

The Jazz Age. But where did the musical form of Jazz come from? And where did the radio and recording industries find the musicians to compose and play it?

In 1939, the jazz bandleader Duke Ellington invited composer Billy Strayhorn to join his band. To get there, he instructed Strayhorn to “Take the A Train.” The “A” is a New York City subway that travels “uptown” to the district known as Harlem.

These instructions had been sent along to thousands of African Americans seeking relief from brutal discrimination and segregation in other parts of the country. In the early decades of the 20th Century, Harlem provided Black people with sanctuary and opportunity that was hard to match in other regions. Let’s take a brief tour of Harlem with the artist Aaron Douglas.

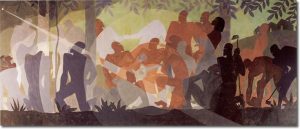

Aaron Douglas: Aspects of Negro Life

In 1934, Aaron Douglas painted a series of four oils representing key eras in the history of a people. The 1st panel looks in on African people celebrating their culture, its music, its art, and its warrior pride. The scene is an imaginative projection by an African American of what African culture might have been like before it was disrupted by European colonialism and slavery. Notice the layered technique: flattened profiles defining zones of depth without perspective. And don’t miss the haloes and shafts of light that organize the composition, centering on the cultural figurine.

|

|

| Panel 1: The Negro in an African Setting | Panel 2: From Slavery Through Reconstruction |

The 2nd panel reviews the long years of slavery, often in cotton fields, and the Union troops breaking its chains. Haloes of light focus our eyes on the Emancipation Proclamation held by a Frederick Douglas-like character looking to the Federal Congress that banned slavery in the 13th Amendment.

Panel 3 celebrates African Americans freed from slavery and gathered to sing of their culture. To the right we see hard labor in the fields, the only work permitted them. In the background, ghostly figures suggest lynch mobs and systematic oppression. Piercing the image and its layers of light is a single ray emanating from a star and offering faith and hope.

|

|

| Panel 3: an Idyll of the Deep South | Panel 4: Song of the Towers |

The 4th Panel proclaims a degree of triumph. One figure struggles to escape ghostly hands. Another clambers up the rungs of a massive gear. A third rises in triumph heroic figure, holding a saxophone to the light that pierces the massed ranks of skyscrapers in New York City.

The Great Migration

In the aftermath of the American Civil War, the Federal government for a time offered Freedmen, i.e. liberated slaves, protection of the Army and support from the Freedmen’s Bureau. Within seven years, however, Freedmen were left to the predatory vengeance of disgruntled white citizens resentful of the war and of any challenge to their complete social dominance. Black southerners were essentially re-enslaved through violence, the suppression of the vote, and a system discrimination built into so-called Jim Crow laws.[1]

[1] Jim Crow Laws: the systematic segregation and discrimination of African Americans built into legal codes in the Southern states were labelled Jim Crow in a vicious references to a well-known Black minstrel show character who was constantly shown displaying his inherent inferiority to white culture.

Conditions became so onerous that waves of African American began to migrate north to states which provided industrial jobs and more subtle forms of discrimination. Black people flocked to Chicago, Detroit, Baltimore, Boston, and, above all, New York.

|

| Arthur family arriving in Chicago. (September 4, 1920). Chicago Defender. |

Due to a real estate crash in 1904, African American found they could actually own property in Harlem, the norther district of Manhattan. The enormous city provided employment opportunities, often menial but still decently paid. In Harlem, a body could do pretty well.

Contrary to well-entrenched stereotypes, we can see prosperity in the figures photographed by James Van Der Zee, a Harlem photographer who did a brisk business in portraiture. Van Der Zee’s subjects do pretty much what all Americans did, gathering for family portraits and “Stepping Out” in their finery.

|

|

|

|

| Family Group. (1934). | Portrait of Two Brothers and Their Sister. (1931). | Stopping In. (1936). | Portrait of Couple with Raccoon Coats & Stylish Car (1932). |

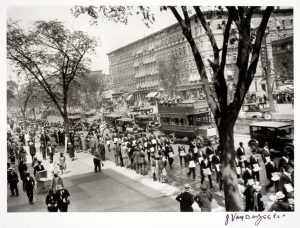

Harlem folk took special pride their soldiers. The 369th Infantry Division overcame extreme systemic discrimination in the Army to win extensive combat honors in the fighting in France.

|

|

| James Van Der Zee. (1932). Soldiers on Parade, Harlem. | Kelly Miller. (1919). New York, cheers Negro Veterans; The 369th Colored Infantry. |

Predominantly Black neighborhoods like Harlem emerged in a wide range of cities: Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, and more. But in the 1920s, Harlem would become the epicenter of a powerful eruption of African American cultural achievement: the Harlem Renaissance.

|

| Winold Reiss. (c 1925). Interpretation of Harlem Jazz I. Offset lithograph and halftone |

References

Arthur family arriving in Chicago [Photograph]. (September 4, 1920). Chicago Defender. Wikimedia Commons https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Great_migration.jpg#cite_note-1

Douglas, A. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life. Panel 1: From Slavery to Reconstruction [Painting]. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/634c59a4-6f99-3618-e040-e00a180633b0

Douglas, A. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life. Panel 2: From Slavery to Reconstruction [Painting]. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/634ad849-7832-309e-e040-e00a180639bb

Douglas, A. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life. Panel 3: An Idyll of the Deep South. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/634c04bc-fed3-b0e8-e040-e00a18063c1a

Douglas, Aaron. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life: Panel 4: Song of the Towers [Painting]. New York, NY: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6ca557ed-9597-5dcd-e040-e00a18065af4

Leininger-Miller, T. (2011). Harlem Renaissance. [Article]. Marter, J. (Ed.), The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195335798.001.0001/acref-9780195335798-e-861.

Miller, Kelly. (1919). Fifth Avenue, New York, cheers Negro Veterans; The 369th Colored Infantry [Photograph]. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image 1206640 https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-7baa-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Reiss, W. (c.1925). Interpretation of Harlem Jazz I [Lithograph]. Washington DC. Library of Congress, DI cph.3g05687. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97516539/

Van Der Zee, J. (1934). Family Group [photograph]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 2021.443.252. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/847859

Van Der Zee, J. (1932). Portrait of Couple with Raccoon Coats & Stylish Car [Photograph]. Washington D.C. National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2021/james-van-der-zee-photographs-portrait-harlem.html

Van Der Zee, J. (1931). Portrait of Two Brothers and Their Sister [Photograph]. Washington D.C. National Gallery of Art. AN 2021.22.1.15. https://www.nga.gov/artworks/223864-portrait-two-brothers-and-their-sister

Van Der Zee, J. (1920). Soldiers on Parade, Lenox Avenue near 134th Street, Harlem [photograph]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 2021.443.402. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/848009

Van Der Zee, J. (c 1936). Stopping in [Photograph]. Wellesley MA: Davis Museum at Wellesley College. Accession Number 1998.8. https://davis.emuseum.com/objects/4912/stopping-in?ctx=4f2cacc5d9c1fd924dedab68460c8457b975bd80&idx=1