14.2 The Roaring Twenties

In an inconceivably grim twist of fate, World War I was immediately followed by an influenza pandemic that killed hundreds of thousands more victims. Then, as the 1920s dawned, things lightened up.

Once the inevitable war’s-end recession lightened up, the economy in many nations roared into high gear. Industrial development exploded, agricultural production reached new heights through mechanized implements, and consumer-oriented manufacturing pioneered unprecedented markets. The decade following the Great War was labelled the Roaring Twenties.

Ain’t we got fun?

How do you listen to music? You-Tube? Spotify? Tik-Tok? In a video or movie? On the radio? Maybe, if you’re as old as I am, on a CD? A vinyl record?

Can you imagine a world of music in which recording, broadcast, or streaming options did not exist? In which you could only hear music in the presence of the performing musician?

One of the most impactful consumer developments in the late 19th Century was the invention of gramophones—record players. For the price of a hamburger lunch, one could buy a recording of music that could be played again and again thousands of miles away from the performers.

By the 1920s, the recording industry, centered in New York City, shared the work of talented musicians with the world. Around the same time, radio networks began transmitting to owners of affordable receivers. The programming ranged from news to drama with a strong emphasis on music. One could go into the living room, turn the dial and hear major orchestras perform classical compositions.

One could also hear pop music. Dance bands and popular tunes flooded the airwaves and record stores. In a massive reflex away from the miseries of the previous decade, musicians led people into a feverish embrace of good times.

Gus Kahn, Raymond B. Egan and Richard A. Whiting. (1921) Ain’t we got fun?

Bill collectors gather

‘Round and rather

Haunt the cottage next door

Men the grocer and butcher sent

Men who call for the rent

But with in a happy chappy

And his bride of only a year

Seem to be so cheerful

Here’s an earful

Of the chatter you hear

Every morning

Every evening

Ain’t we got fun

Not much money

Oh but honey

Ain’t we got fun

The rent’s unpaid dear

We haven’t a bus[1]

But smiles were made dear

For people like us

In the winter in the Summer

Don’t we have fun

Times are bum and getting bummer

Still we have fun

There’s nothing surer

The rich get rich and the poor get children

In the meantime

In the between time

Ain’t we got fun.

Just to make their trouble nearly double

Something happen’d last night

To their chimney a gray bird came

Mister Stork[2] is his name

And I’ll bet two pins

A pair of twins

Just happen’d in with the bird

Still they’re very gay and merry

Just at dawning I heard

Every morning

Every evening

Don’t we have fun

Twins and cares dear come in pairs dear

Don’t we have fun

We’ve only started

As mommer and pop

Are we downhearted

I’ll say that we’re not

Landlords mad and getting madder

Ain’t we got fun

Times are so bad and getting badder

Still we have fun

There’s nothing surer

The rich get rich and the poor get laid off

In the meantime

In between time

Ain’t we got fun.

Billy Jones recording. (1921). Ain’t we got fun? YouTube audio

The relentless cheeriness of this song reflects the determination of people determined to leave the bad times behind them. But the starkly ironic, even sarcastic lines testify to the lingering poverty shared by so many people, including veterans who returned from war to find they had been left a share in poverty.

That satirical refrain, Ain’t we got fun, gestures toward a host of injustices. And yet it also expresses a very real commitment to find pleasure in life. People thronged dance halls, bought records, and listened to radio dramas and comedies. Popular tastes shoved Classical preferences aside as people learned swing dances like the Lindy Hop, the Jitterbug, and the Charleston and embraced the signature music of the Jazz Age.

Glamor in the Camera Lens

The other great innovation in entertainment was, of course, the cinema. Motion pictures were developed by the Edison Company and the Lumiere brothers in Paris. Within a decade, the movies had grown into a major industry producing thousands of films watched by millions worldwide. It would be wonderful to take up that tale, but let’s just note an offshoot of the film world: glamor photography.

Motion pictures quickly made stars out of handsome men and beautiful women, and glamor magazines featured Douglas Fairbanks, Clara Bow, Greta Garbo and Rudolf Valentino as well as models selected for appearances that met the tastes of the day.

|

|

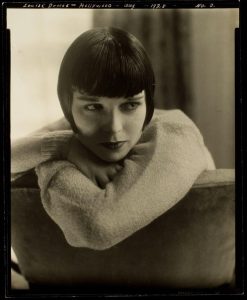

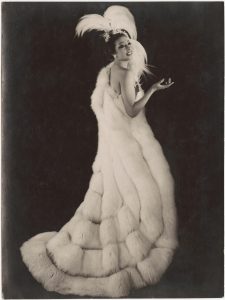

| Edward Steichen. (1928). Louise Brooks. | Josephine Baker. (c 1935). |

And in the case of women, these tastes were changing. Thousands of women had worked in munitions factories when men were at the front. Women were demanding the vote and reforms of laws that restricted their work and financial opportunities. Women were stepping out into dance halls and insisting on their rights to share in the good times of the day.

The result was a new social paradigm available to women. The Flapper was a nervy young woman who threw off the restrictive clothing of the past, wore loose fitting frocks, enjoyed music and dancing, and chose her own course in sexual relations. American actress Louise Brooks wore her hair in the short, “bobbed” style of the day and played roles that scandalized many but expanded the possibilities for many women oppressed by conventional restrictions.

Josephine Baker was a dancer and singer who moved to Paris to enjoy far greater career possibilities than were available to an African American young woman in the United States. Like Brooks, she lived a lifestyle that defied the gendered and racialized boundaries of the day. Glamor photographers were helping to open conceptual doors to previously unthinkable possibilities.

Speed and Glamor: Tamara de Lempicka

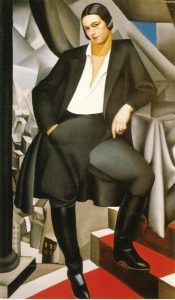

Daughter of an affluent Polish-Jewish attorney, Tamara de Lempicka and her husband fled persecution after the Russian Revolution. During the 1920s, she earned notice in American glamor magazines and gained commissions as a portraitist painting in the Art Deco style.

|

|

|

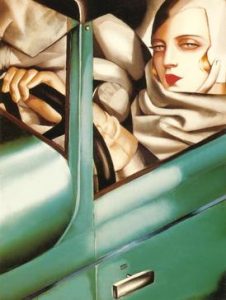

| Portrait of Dr. Boucard. (1929). Oil on Panel. | Portrait of the Duchess of La Salle. (1929). Oil on Panel. | Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti) (1929). Oil on Panel. |

Art Deco was a sort of simplified version of Neo-Classical design. It emphasized elongated, graceful shapes and Geometrical Forms. de Lempicka’s portraits of affluent and famous people pictured them with the lean elegance that was in demand at the time.

de Lempicka’s Autoportrait draws from some of the strongest themes of the day. A feverish love of mechanical speed supported races of every type: automobiles, aeroplanes, speedboats, even bicycles. Thousands bought cars to have the option for speed at their feet and hands. In her self-portrait, she links herself to that speed and proclaims her independence as a woman daring to live life on her terms.

Vital Questions

Context

Few moments in world history were as pivotal as the 1910s and ‘20s. A staggeringly catastrophic war transformed people’s notions of power, warfare, and the role of the state. Then the reaction to that war sent popular culture careening off the rails of convention during the media revolution of film, recorded music, and broadcast programming.

Content

In contrast to the Modern moment that preceded the war, post-war art struck an uneasy balance between haunted memories of the War and a resolute need to look forward. It turned increasingly to the “democratic” experience and themes of ordinary people. In literature, the engagement of Hemingway and Owen with horrors of the age mark a fresh boldness in taking on individual and social darkness. Much more of this would follow.

Form

We can notice in Owen and in Hemingway a stripping down of Form. Owen abandons Meter and Rhyme in favor of the rhetorical rhythms of Free Verse. Hemingway pares the Narrating Voice to the bone and beyond. Images. Facts. Pure experience. Readers are pressed into engagement with the Narrative moment.

Meanwhile, pop song writers are gleefully abandoning any responsibility to the rules of edited English. “Ain’t We Got Fun?” is steeped in the slang expressions of the day. The lyricists don’t mind. And just imagine the impact of such a song blaring from thousands of gramophones and radio sets on the tender ears of those trained to tolerate only formal diction and syntax! Art is taking it to the streets.

References

Jones, B. (1921). Ain’t we got fun? [Song recording]. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uF6DMubhiLE

Kahn, G. Egan, R. B., and Whiting, R. A. (1921) Ain’t we got fun [Song]. Wikisource https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Ain%27t_We_Got_Fun

de Lempicka, T. (1929). Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti) [Painting]. Private Collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/tamara-de-lempicka/portrait-in-the-green-bugatti-1925

de Lempicka, T. (1929). Portrait of Dr. Boucard [Painting]. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/tamara-de-lempicka/portrait-of-dr-boucard-1929

de Lempicka, T. (1929). Portrait of the Duchess of La Salle [Painting]. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/tamara-de-lempicka/portrait-of-the-duchess-of-la-salle-1925

Steichen, E. (1928). Louise Brooks [Photograph]. Rochester, NY: George Eastman House. AN 1979:2088:0001. https://collections.eastman.org/objects/11262/louise-brooks?ctx=85a19f08-ad19-4423-9051-8cc06b674a2d&idx=0

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

a style in the arts associated with the early 20th Century that emphasized formal design and the surface of the medium over any represented or narrated subject

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

a disciplined pattern of sound units throughout the lines of a poem. In English verse, meter is found in the number and a pattern of stressed and un-stressed syllables in a line

a pattern of repeated sounds, usually the final syllable in the ends of verse lines

(in French, "vers libre") poetry that achieves verbal rhythms through repetitive, often parallel figures of speech, Tropes and Schemes. Free verse does not establish set patterns of meter or rhyme.