12.2 Impressionism’s Heirs

In a recorded concert of the 1970s, the great Joni Mitchell teased the audience about anguished pleas for this or that song (1974):

Mitchell, herself an accomplished painter, felt confident that mentioning van Gogh’s most famous painting would connect with an audience of music lovers. Indeed, van Gogh is today one of the most revered painters on earth. A quick glance at one of his paintings will make clear the influence of Impressionism on his work. And yet, something else seems to be going on there. Seurat, van Gogh, Gauguin—all emerged out of the Impressionist movement, but each opened new dimensions of expression. This is the generation of artists loosely labelled as the Post-Impressionists.

To get a grip on the Post-Impressionists, let’s return to a question we have asked repeatedly. What is a painting supposed to do?

We have been exploring the Mimetic tradition that developed in Classical Greece, was set aside during the Byzantine period, and resumed during the Renaissance. This tradition established Illusionism as a primary goal of art: the responsibility to accurately imitate the appearance of a visual subject or scene so that it seems to be “the real thing.”

We have also explored core components of that commitment. Accurate, detailed drawing and modeling of the subjects and figures. Linear perspective and Foreshortening. Internal light sources and shadows. Descriptive color that matches the hues of “nature.” These values became so strong that the academies used them to articulate rules that governed fine art.

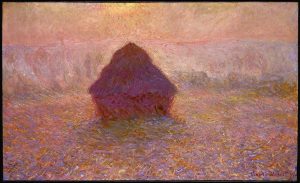

We then explored the Impressionist rebellion against these rules. Impressionists shifted the focus from detailed drawing to a focus on the media through which one sees: light and atmosphere. Monet, for example, was not interested in precise imitation of faces and fabrics. But he did care immensely for accuracy in capturing the play of light and color. He had shifted its target, but his commitment to a different sort of mimesis remained intense.

|

|

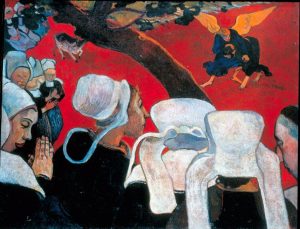

| Claude Monet. (1891). Grain stack, Sun in the Mist. | Jacob Wrestling with the Angel of the Vision After the Sermon. (1888). |

Meanwhile, Paul Gauguin, deeply influenced by the Impressionists, had taken a further step in challenging the Renaissance Model of painting. Can you see what that step is? How has Gauguin processed from shifting the camera’s lens to breaking away altogether from the “real thing” it looks upon?

References

Gauguin, P. (1898). Vision after the Sermon [Painting]. Edinburgh, Scotland: National Galleries of Scotland. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/artists/paul-gauguin

Mitchell, J. (1972). For the Roses. Asylum.

Monet, C. (1891). Grain stack, Sun in the Mist [Painting]. Minneapolis MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/10436/grainstack-claude-monet