11.4 Impressionism: the Window Reframed

Four hundred years after Leonardo, the Renaissance Model continued to dominate European painting. Preferred subjects were religious or historical. Visually, a painting’s content was conceived as a naturalistic illusion of what one could see looking out on a “real” scene through the window frame of the canvas. Elite painters were expected to create this illusion through accurate linear perspective, foreshortening, and detailed modeling.

But the world was changing. Painters were reformulating that Renaissance window and Western art would never be the same.

Degas: the Snapshot Frame

As we have seen, many painters used photographs as preliminary templates for painting. Edgar Degas was fascinated by photography and, in the 1890s, took it up with enthusiasm.

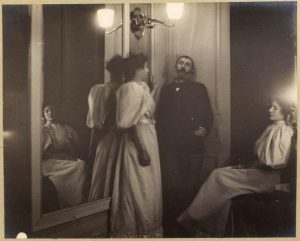

|

|

|

| Portrait in a mirror of Henry Lerolle and daughters. (1895). | Dancer Adjusting Shoulder Strap. (1896). | Photograph of Renoir (seated) and Stéphane Mallarmé. (1898). |

Of course, one can’t take a photograph of a long dead monarch. As a medium, photography locks one into the content of one’s surrounding world. One of the obstacles to photography being taken seriously as an art form was its democratic content. I mean, really. Chimney sweeps walking across a Parisian bridge? Is that art?

Well, perhaps. Degas was not put off by the status of the ordinary as a subject for art. Consider these three samples of his compositions:

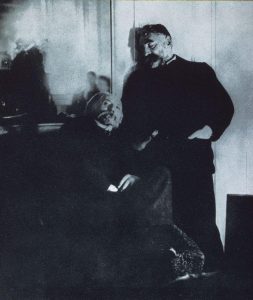

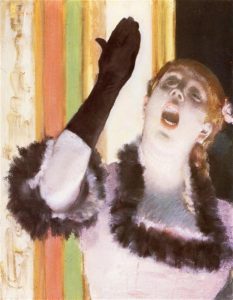

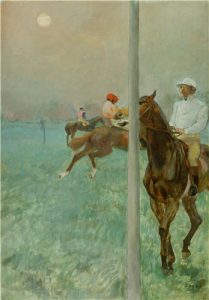

|

|

|

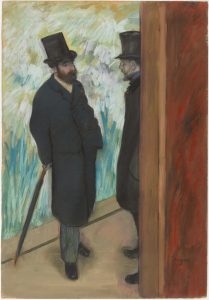

| Singer with a Glove (1878). | Jockeys before the Race. (1879). | Halevy & Boulanger at the Opera (1879). |

Cabaret singers, horses and jockeys, theater goers outside the opera: these are snapshot choices of subjects. It is hard for us today, conditioned as we are by smart phone selfies, to recognize how subversive this choice was. Degas saw no reason not to immortalize the races, opera, ballet, and demi-monde[1] world of cabaret entertainment that he loved.

So the subjects chosen by Degas were subversive to the hypocrisies of the day. But even more subversive was the photographic way he framed those subjects in his canvas window. Degas recognized that a camera lens encompasses whatever fills its frame and ruthlessly cuts off everything else. Think of awkward family snapshots. Uncle Fred’s head is sliced off. Aunt Dolly’s eyes are closed. Little Angela sticks her tongue out at her brother. Grandpa Al is standing off, creating a spatial imbalance. The light machine takes it all in.

Photographers refer to a shot’s hard boundaries as cropping. All components outside the frame will be cropped out. Traditional painters meticulously compose scenes to balance subjects and avoid cropping significant figures. While a good photographer can emulate such composition, most photos enclose sliced off figures and asymmetrically balanced spaces.

Degas recognized the appeal of a snapshot’s offbeat composition. In the late 1870s, he began to experiment with a loose, asymmetrically balanced composition that crops its subjects in the manner of a snapshot. Above, we see a singer whose arm has been cropped despite her primacy as the sole figure in the image. The composition of jockeys and horses is seriously imbalanced, and the near horse is cropped on the right and blocked behind an awkwardly placed pole. The opera-goer on the right is blocked by an insignificant wall filling the entire right side of the image. In these compositions, Degas appropriates a snapshot aesthetic.

Two major compositions embrace Parisian nightlife with photographic composition. The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage honors the craft and labor of performers who were lusted after and despised as little more than sex workers by the socially elite men who thronged the theaters and cabarets. Degas honored them in dozens of paintings and sculptures.

From a sheerly formal perspective, Degas composes rehearsing ballerinas in an elegant spiral around the dark-clad dance master. Layered set decorations and the stage left wings balance a horizontal background with an open, negative space on the apron. Yet the formal unity of the composition seems imposed on discrete dancers, each lost in a private world of drill. A pair of support staff lounge disinterestedly on chairs. Like a candid snapshot, this painting captures randomly gathered figures who display no interest in contributing to the photographer’s composed vision.

|

|

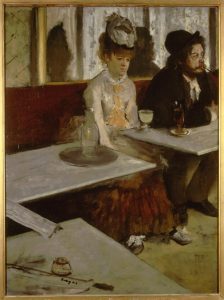

| The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage. (1874). | In a Café (Absinthe Drinker). (1876). |

In a Café (absinthe[2] drinkers) frames desultory middle-class figures, plain in appearance and plainly dressed, sitting above their drinks. Lit unsympathetically by daylight, the couple looks off into space, disconnected from each other. Our point of view stands at a dramatic, slanted angle to the café patrons. The tables form a canted right angle that divides positive and negative zones cross-cut by light. The painter’s canvas acts as if it were a camera.

[1] Demi-monde: “half-world” or underground society of disreputable members of society often surreptitiously visited and patronized by aristocratic and middle class who maintained respectful public facades.

[2] Absinthe: a potent alcoholic drink flavored with anise and other herbs that was popular in the late 19th Century for its rumored hallucinogenic properties.

The Impressionists: Exploring the Frame

As Degas begins to readjust the artist’s window frame, we begin to wonder just how stable that Renaissance model of painting really is. Consider this:

|

| Magritte, René Magritte (1955). The Promenades of Euclid. Oil on canvas. |

In 1955, René Magritte slyly problematized the authority of the artist’s window frame. The frame of his canvas encompasses two other frameworks. It displays an actual (?) window looking out onto the Virtual Space of a street scene. Imposed on part of that windowpane is an easel with a depiction of the scene so apparently precise that we struggle to determine the boundary separating window from canvas.

But we must remember that we are separated from that outside “reality” by three layers of vision: canvas 1, canvas 2, and windowpane. What is “really” out there? For example, is the tower “actually” out there on the street or has the painter added it?

Magritte’s visual jest draws on nearly a century of art which increasingly problematized and reformulated our notion of art’s window on the world.

les Refusés: the Gleyre CIrcle

In the 1860s, young artists such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir studied in the studio of the traditional painter Charles Gleyre. They developed close relationships with Degas, Éduard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, and others. These artists shared the experience of having their works rejected by the Academie des Beaux Arts. In the 1870s, frustration was growing.

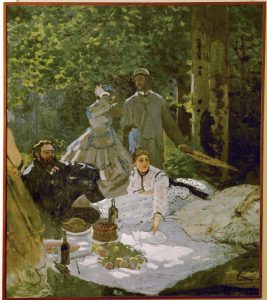

You guessed it: one reason they were rejected was their choice of subject matter. Like Degas, they chose not to paint grand compositions of historical glory, but rather the world around them. Their social world was that of the Parisian middle class, a class determined to enjoy its leisure time. The developing railway system permitted people of modest means to enjoy previously unaffordable excursions. On Sundays, people would gather in parks, explore the Seine in boats, or gather in cafes and cabarets.

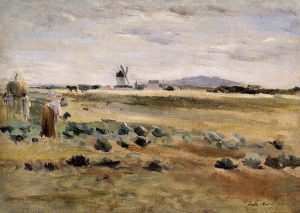

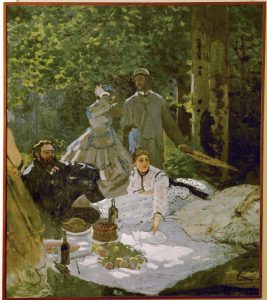

|

|

| Claude Monet. (1865). Le dejeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) | Berthe Morisot. (1875). The Little Windmill at Gennevilliers. |

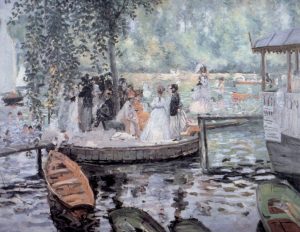

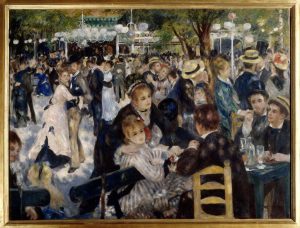

Pierre-Auguste Renoir composed ambitious, large-scale views of people at leisure. One can get lost in Renoir’s complex compositions of subjects, each figure telling a story.

|

|

|

| Luncheon of the Boating Party. (1869). | La Grenouillere. (1869). | Dance at Moulin de la Galette. (1876). |

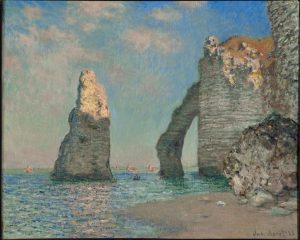

The harbor of Le Havre on the coast of Normandy is 122 miles from Paris. Before the railway, this journey would have taken days. In the 1870s, middle class workers could take a quick run to the sea. Monet, Morisot, and the others joined them, painting seascapes of resort and shoreline features such as the natural arc at Étretat. Monet particularly embraced Normandy, returning again and again and eventually making his home and studio in Giverny.

|

|

|

| Claude Monet. (1867). Garden at Sainte-Adresse. | Claude Monet. (1885). The Cliffs at Étretat | Berthe Morisot. (1869). The Harbor at Lorient [Brittany, west of Normandy] |

the Salon des Refusés: Impression’s Birthplace

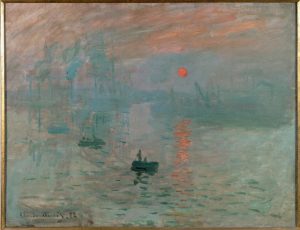

These artists chose subjects which the art establishment disrespected. But there was more to come. In 1874, a showing of rejected artists shocked the art critic Louis Leroy whose complaints centered on one painting by Monet Impression, Sunrise (1872). Disgusted by what appeared to be amateurish, loosely composed, inept technique, he complained of “these Impressionists” (Who Was Louis Leroy? 2021). The name stuck.

So imagine you were at that salon: what would you think?

|

| Claude Monet. (1872). Impression, Sunrise. |

Now let’s put your experience in context. Remember that your ideas of proper painting would have been shaped by the tastes of the academies. Remember, too, that people were getting used to the precise accuracy of photographs.

|

|

| Fitz Hugh Lane. (1862). Stage Fort across Gloucester Harbor. | Thomas Sutton. (1855). Harbor Scene. Salted paper print. |

OK, what would you think? After all, the criterion for painting excellence is the illusion of visual authenticity derived from meticulous perspective, foreshortening, drawing, and modeling. By those standards, does Monet’s painting hold up?

Recording the Medium: Claude Monet

When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have in front of you, a tree, a field. … merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives your own naive impression of the scene.

-Claude Monet, quoted in Dunstan, (1976) p. 46.

Now, the brilliant Claude Monet could certainly compose images to be considered, by traditional standards, much more accomplished:

|

|

| Claude Monet. (1865). Le dejeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass). Oil on canvas. | Claude Monet. (1867) Garden at Sainte-Adresse. Oil on canvas. |

All right, so if Monet could paint so well in 1865, why is he, a few years later, doing so poorly? The answer, of course, is that Impression: Sunrise is not applying academic techniques poorly. It is, instead, playing a different game. Indeed, he is painting wholly different Content.

Monet is not, as Sutton and Lane were doing, attempting to depict boat, water, and harbor. He is painting, as his title suggests, his Impression of a split second of visual time. This is how he perceives the scene that spreads out before him. That scene includes boats, but, as his quotation above makes clear, he is really painting pure visual experience.

Have you ever noticed that holiday postcards, scenes from television shows, and photos of national parks always seem to be taken on perfect, cloudless days drenched in sunshine? The assumption is that we want to see the real thing, not clouds or mists that obscure it.

But a painter honestly portraying a moment of perception must paint it all, including the atmospheric conditions that shaped the vision. For Monet, objects and atmosphere burred into an undifferentiated visual mass which he meticulously depicted in paint. That meant fidelity to a particular set of visual conditions: light, weather, atmosphere. If he began a painting with the light at a certain angle, he could not work until the conditions returned. He is quoted as having once said to Degas, “I’m half an hour late. I’ll have to come back tomorrow” when the light was right (Dunstan, p. 53).

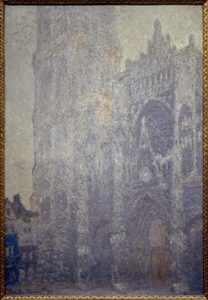

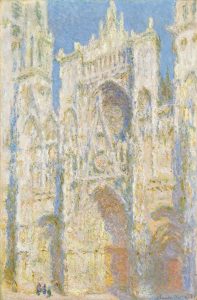

Monet’s work is always sensitive to the conditions of vision, as we see in his series of over 30 versions of the same “subject”: the West Front of Rouen Cathedral. Atmospheric conditions, however, transform this identical subject into profoundly different experiences.

|

|

| Rouen Cathedral, Morning Light (1893). Oil on canvas. | Rouen Cathedral, Fog (1893). Oil on canvas. |

|

|

| Rouen Cathedral, Sunlight. (1893) Oil on canvas. | Rouen Cathedral, Partial Sun (1894). Oil on canvas. |

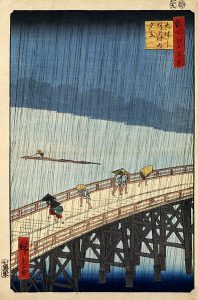

Now, Monet was not innovating out of nothing. He was influenced, as were many artists of the day, by Japanese woodcut prints that always seemed to include weather conditions. Japanese prints still festoon the walls of Monet’s home at Giverny as they did in his day. Some of these prints came in series of views of the same object, inspiring the Rouen Cathedral series.

|

| Ando Hiroshige. (1858). One Hundred Views of Famous Places in Edo: Squall at Ohashi. |

En Plein Air

If one sets out to meticulously capture a visual experience of, say, a landscape or seascape, one is drawn outside the studio. Traditional painting might begin with a sketch in an external location, but the final composition evolved in the studio over a period of weeks.

|

|

| Paul Cézanne. (1875). A Painter at Work. | Éduard Manet. (1874). The Boat (Claude Monet, with Madame Monet, Working on his Boat in Argenteuil) |

One of the points of pride of academic art was the grueling, meticulous studio process in which painters sought a form of perfection through weeks of meticulous drawing and oil paint worked and re-worked with vanishing brushwork. The Impressionists pioneered a more immediate technique, working en Plein Air, i.e. out of doors at the scene.

Some practical innovations in art equipment supported the move out of the studio. Already mixed paints were available in tubes; canvas, easel, and brushes could be carried by hand in portable kits. These innovative products enabled Impressionists to work quickly on the scene.

Critics were appalled by the improvised, apparently lazy techniques that we see in the work of Paul Cézanne, shown above at work en plein-air. It took time for the art world to learn to see through the eyes of an artist which a different understanding of detail.

Paint, Brushstrokes, Canvas: The Emergence of the Medium

“Forget what objects you have in front of you,” advises Monet. Suppose a painter follows his advice. What formal aspects of traditional painting will recede? Line, for one. Well drawn objects are defined by contour lines, modeling, Linear Perspective, Foreshortening: all of the tricks in the Renaissance tool kit. To paint an atmospheric Impression, one need not capture the detailed appearance of, for example, the faces of the passersby on a street scene. Indeed, Impressionists often felt that since contour lines are not found in nature, they should not appear on the canvas.

On the other hand, three formal elements receive an innovative form of emphasis: color, light, and Texture. An Impressionist depiction of a sea or landscape can ignore details of form but it will obsessively cultivate the “truth” of light and color. A common technique was le petite tache, the small, often minute brushstroke (Dunstan, 1976, p. 51). Amassed in the thousands, these strokes can suggest the line and form of an object while fusing it with atmospheric light and color.

Short strokes offered a fresh way of achieving complex color. Traditionally, artists mixed their colors on their palettes and then painted the color directly. Impressionist technique would place short strokes of unblended colors next to each other, allowing them to blend within the viewer’s eye, creating the subtle coloration that these painters so loved. Dunstan warns us that this technique would be more fully developed later by others but acknowledges that Impressionists formed colors through “tones built up by separate touches” (p. 43).

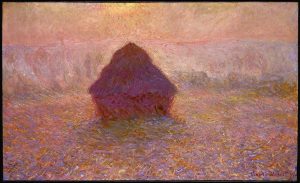

A stunning example of this technique is found in one of Monet’s series of grain stack paintings. Stand back and you perceive a gauzy, hazy fusion of complex colors and light. Step up close: in person at the Minneapolis Institute of Art or the high-quality photograph on the MIA’s website. You will be able to see an overwhelming tapestry of tiny strokes laid against each other.

|

|

| Claude Monet. (1891). Grain stack, Sun in the Mist. | Pierre-Auguste Renoir. (1881). The Piazza San Marco (Venice) |

Pierre Renoir, a close confidant of Monet’s, painted for a time with Impressionist technique. Observe le petite tache in his impression of St. Mark’s Square in Venice. Notice how the form and definition of objects and figures have receded behind a flattened expanse of light and color. Pedestrians and pigeons are indicated with deft strokes of the brush.

Notice, too, how, as the impact of depicted subjects recedes, the texture of the medium is foregrounded in our awareness. We see and feel individual strokes and the textures of paint and underlying canvas.

Berthe Morisot

As girls, Berthe and Edma Morisot received the conventional education that prepared women for life as bourgeoisie wives. Included was conventional instruction in watercolors and the less honored genres of painting. By the late 1860s, she was embracing the aesthetic of Impressionism as embodied by her brother-in-law, the pioneering painter Éduard Manet.

Four hundred years after Artemisia Gentileschi, women had earned some standing as artists. Morisot initially received some acceptance by the Académie des Beaux Arts. But women artists were accepted best for domestic subjects supporting ideas of motherhood. Morisot’s The Cradle seems conventional enough until we realize that the woman—mother? Governess?—and child are separated by a veil and the woman’s gaze is more reflective than adoring.

|

|

|

| The Cradle. (1872). | Eugene Manet with his daughter at Bougival. (1875). | By the Water. (1872). |

As a respected member of the Impressionist clique, Morisot explored their subjects and techniques. The title of her loving portrayal of husband and daughter does not give away her relationship to them and the forms, colors, and light are executed with minimal contours and short strokes of color laid against each other. By the Water is even bolder, presenting father and daughter in an outline format of sketched lines in bold colors enclosing open areas of pale, negative space.

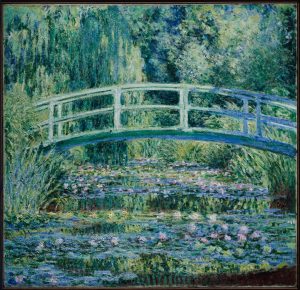

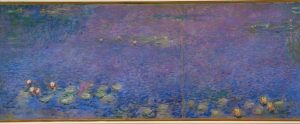

Impressionism’s aftermath

Today, Monet is probably best known for his extensive series of paintings composed in his gardens at Giverny, Normandy. Thousands each year visit his home, studio, flower gardens, and meticulously fashioned lagoons. Monet designed the grounds as an artistic composition in its own right. Flower beds are arranged according to the sequence of hues in the color wheel. Ponds and bridges emulate Japanese models. Aging, losing his eyesight, and appalled by the fearsome impact of World War I on France, he gave a series of massive water lily compositions to his nation.

|

|

| Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge. (1899). | Water Lilies. (1917). |

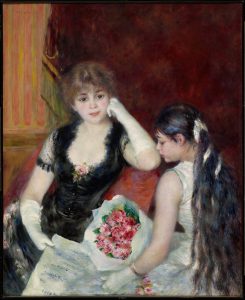

Monet remained true to Impressionist convictions throughout a long career. Others had a tendency to wander off. Renoir, for example, became impatient with the limitations of Impressionist technique. He felt that the movement away from form led away from sound composition, a concern shared by Georges Seurat and other Post-Impressionists. His later compositions were both luminous and relatively conventional:

|

|

| A Box at the Theater. (1881). | Girls at the Piano. (1892). |

Vital Questions: Impressionism

So, Impressionism. You’ve most likely heard the term and you might have a sense of what it refers to. But what should we see and understand?

Context

Remember that this is the middle of the 19th Century. Industrialization, capitalism, and railways are transforming society and empowering the middle class. Photography has arisen as a competitor to painting and offered a poorly understood but emerging alternative aesthetic. Painters can get around on trains and carry mini-studios with them, complete with tubes of pre-mixed paint. They are eager to head outdoors.

Content

The most obvious shift in content is an embrace of middle-class life in all its ordinary glory. Less obvious but more profound is the reformulation of the Renaissance notion of a painting as a window on the illusion of a world seemingly real due to mimetic techniques.

The Impressionists pulled back the lens of their window to paint, not the objects and subjects we imagine being “out there,” but the perceptual pane of glass through which we receive impressions of a visual moment. Think of Monet painting the cathedral at Rouen over and over, his subject being not the building, but the atmospheric conditions through which he views it.

Form

Because an Impressionist image is interested in atmosphere and fused perception rather than Illusionism, it avoids or at least reduces the use of Line to articulate form. It focuses on the formal elements of light and color and executes these with light, quick strokes of the brush. The Textures of these Media rise to our foregrounded awareness and in themselves convey Aesthetic effects. The influences of this shift continue into our own day as fractional, gestural bits of medium take on weight and impact in industrial design, advertising, and graphic compositions.

References

Cézanne, Paul. (1875). A Painter at Work. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Retrieved from https://www.wikiart.org/en/paul-cezanne/a-painter-at-work-1875

Degas, E. (1878). Dancer with a Bouquet of Flowers with ballerina Rosita Mauri. Private collection, Getty Center, Los Angeles. Oil on canvas. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edgar_Germain_Hilaire_Degas_069.jpg

Degas, E. (1874). The Dance Class [Painting]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. AN 1987.47.1.. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438817

Degas, E. (1896). Dancer adjusting her shoulder strap [Photograph]. Paris, FR: Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Stanska, Z. Rare photographs by Edgar Degas. (January 22, 2024). Daily Art Magazine. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/this-photographs-taken-by-edgar-degas-will-sweep-you-off-your-feet/

Degas, Edgar. (1875 – 1876). In a Café (Absinthe Drinker) [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/dans-un-cafe-1147

Degas, E. (1879). Jockeys before the Race [Painting]. Brimingham, UK: Barber Institute of Fine Arts. 1950 (No. 50.2) https://barber.org.uk/edgar-degas-jockeys-before-the-race/

Degas, E. (c 1874). The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage [Painting]. New York NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. AN 29.160.26 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436155

Degas, E. (1879). Ludovic Halevy et Albert Boulanger-Cavé dans les coulisses de l’Opéra [Halevy and Boulanger at the Opera] [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musee dÓrsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/ludovic-halevy-et-albert-boulanger-cave-dans-les-coulisses-de-lopera-3002

Degas, E. (c 1898). Photograph of Renoir (seated) and Stéphane Mallarmé [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Degas,_Edgar_-_Renoir_und_Mallarm%C3%A9_(Zeno_Fotografie).jpg

Degas, E. (1895). Portrait in a mirror of the painter Henry Lerolle and his two daughters, Yvonne and Christine [Photograph]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay AN PHO 2004 4. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/portrait-au-miroir-du-peintre-henry-lerolle-et-de-ses-deux-filles-yvonne-et-christine-132769

Degas, Edgar. (1878) Singer with a Glove. Pastel on canvas. Cambridge, MA: Fogg Museum, Harvard University. https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/228652?position=31

Dunstan, Bernard. (1976). Painting Methods of the Impressionists. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications.

Hiroshige, Ando. (1858). Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake. From One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. [Woodcut]. New York: N Y. Metropolitan Museum of New York. AN JP643. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/36461

Lane, Fitz Hugh. (1862). Stage Fort across Gloucester Harbor [Painting]. New York: N Y. Metropolitan Museum of New York. AN 1978.203. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11396

Magritte, R. (1955). The Promenades of Euclid [Painting]. Minneapolis MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1670/the-promenades-of-euclid-rene-magritte

Manet, Eduard. (1874). The Boat (Claude Monet, with Madame Monet, Working on his Boat in Argenteuil) [Painting]. Munich, GE: Neue Pinako-thek. https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/en/artwork/o5xr0jMG7X

Monet, C. (1885). The Cliffs at Étretat [Painting].Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. https://www.clarkart.edu/ArtPiece/Detail/The-Cliffs-at-Etretat

Monet, C. (1865). Le dejeuner sur ‘herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/le-dejeuner-sur-lherbe-25651

Monet, C. (1867) Garden at Sainte-Adresse [Painting]. New York: N Y. Metropolitan Museum of New York. AN 67.241. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437133

Monet, C. (1877). The Gare St-Lazare [Painting]. London, UK: The National Gallery. AN NG6479 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/claude-monet-the-gare-st-lazare

Monet, C. (1891). Grain stack, Sun in the Mist [Painting]. Minneapolis MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/10436/grainstack-claude-monet

Monet, C. (1872). Impression, Sunrise [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée Marmottan. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/claude-monet/impression-sunrise

Monet, C. (1885). The Manneport, Reflections of Water [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/etretat-la-manneporte-reflets-sur-leau-69346

Monet, C. (1883). The Manneporte (Ėtretat) [Painting]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of New York. 51.30.5. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438823

Monet, C. (1893). Rouen Cathedral: the Portal (Effects of Morning Light) [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/la-cathedrale-de-rouen-le-portail-et-la-tour-saint-romain-effet-du-matin-1289

Monet, C. (1894). Rouen Cathedral, the Portal (Morning Fog) [Painting]. Essen, GE: Folkwang Museum, WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/claude-monet/rouen-cathedral-the-portal-morning-fog

Monet, Claude. (1894). Rouen Cathedral: the Portal (Sunlight) [Painting]. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. AN 30.95.250 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437124

Monet, C. (1894). Rouen Cathedral: the Portal (Sunlight) [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art. AN 1963.10.179. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.46654.html

Monet, C. (1899). Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge [Painting]. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Art Museum https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/31852

Monet, C. (c 1914-1926). Water Lillies [Painting. Detail]. Paris, FR: Musée de l’Orangerie. https://www.musee-orangerie.fr/en/artworks/matin-196303

Morisot, B. (1879). By the Water [Painting]. Private Collection. Wikipedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Morisot_-_by-the-water.jpg

Morisot, B. (1872). The Cradle [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée D-Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/le-berceau-1132

Morisot, B. (1875). Eugene Manet with his daughter at Bougival [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée Marmottan Monet. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/berthe-morisot/the-little-windmill-at-gennevilliers

Morisot, B. (1869). The Harbor at Lorient [Painting]. Washington D.C.: National Gallery. https://www.nga.gov/artworks/52192-harbor-lorient

Morisot, B. (1875). The Little Windmill at Gennevilliers [Painting]. Private collection. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/berthe-morisot/the-little-windmill-at-gennevilliers

Morisot, B. (1873). Reading with Green Umbrella [Painting]. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1950.89

Morisot, B. (1894). Sur un banc au bois de Boulogne (On a Bench in the Woods at Boulogne) [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée D-Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/sur-un-banc-au-bois-de-boulogne-16357

Renoir, P. A. (1881). A Box at the Theater [Painting]. Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. AN 1955.594. https://www.clarkart.edu/ArtPiece/Detail/A-Box-at-the-Theater-(At-the-Concert)

Renoir, P. A. (1876). Dance at the Moulin de la Galette [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/bal-du-moulin-de-la-galette-497

Renoir, P. A. (1869). The Duck Pond [Painting]. Dallas, TX: Dallas Museum of Art. AN 1985.R.56. https://www.dma.org/art/collection/object/4261633

Renoir, P. A. (1892). Girls at the Piano [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. RF 755. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/jeunes-filles-au-piano-1164

Renoir, P-A. (1869). La Grenouillere [Painting]. Stockholm, SW: Nationalmuseum. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/pierre-auguste-renoir/la-grenouillere-1869

Renoir, P. A. (1875). Lovers [Painting]. Prague, Czech Republic: National Gallery. https://sbirky.ngprague.cz/en/dielo/CZE:NG.O_3201

Renoir, Pierre-Auguste. (1869). Luncheon of the Boating Party [Painting]. The Phillips Collection. https://www.phillipscollection.org/collection/luncheon-boating-party

Renoir, P. A. (1881). The Piazza San Marco [Painting]. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1163/the-piazza-san-marco-pierre-auguste-renoir Pierre Auguste Oil on canvas

Sutton, Thomas. (1855). Harbor Scene. [Salted paper print from paper negative]. New York NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. AN 1987.55.1 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/631050

Who Was Louis Leroy? [Article]. (2021). Encyclopedia of Art. Visual-Arts-Cork.com http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/critics/louis-leroy.htm

the conventional values and expectations of painting that derived from the Renaissance tradition: a conception of painting as a window on the world projecting visual space with foreshortening, linear perspective, and accurate mimesis

in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

the material projected by art for the reader’s mind and imagination. Content can consist of an immediate Subject—e.g. a figure in a painting or a story in a narrative—and Signification, a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature

content for a work of art that seeks to capture, not the “real thing,” but rather one’s subjective experience of the subject

the practice of beginning and completing a painting on site, thus sacrificing the finished detail of a long studio process to capture the immediate impression of the scene. A hallmark of Impressionist technique

in visual art, a 2-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth. Line may be straight or curved, directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

an illusion of depth created by contrasting the sizes of objects on the basis of how near or far they are from the eye of the viewer. E.g. a human figure in the foreground will be larger than a tall building in the distance.

in visual art, the illusion of surface feel either of A) the represented object (e.g. textures of clothing) or B) of the artifact’s media (e.g. canvas weave, brushstrokes, daubs of paint)

an aspect of art which is expected and understood by the audience in a particular tradition

the conviction that a painting or sculpture’s most important task is to imitate the appearance of nature as naturalistically as possible

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative

the dimension of an artistic experience that appeals to or challenges an au-dience’s sense of taste and experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A response distinct from “interested” concerns such as ideology, sexuality, social conflict or economics