12.3 Impression to Expression

So how are you coming along? Are you feeling stronger in your responses to art? You may need to be. This is the point at which we begin to engage art that some might consider uncomfortable. The freedom with which Post-Impressionisms broke down the traditional Renaissance Model of composition begins to move away from Illusionism. Lines, forms, and colors begin to take on weight of their own as Aesthetic Contents. Are you ready?

Pixilating the Image–Georges Seurat

At a glance, Georges Seurat seems to be a faithful child of Impressionism, and he certainly believed in its vision. However, Seurat saw a weakness in Impressionism that limited its achievement. He felt that an extreme emphasis on color, light, and Media were compromising the Form and Line of Composition. Think how murky everything seems to be in, for example, Renoir’s The Piazza of San Marco.

Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières follows Impressionist practice in depicting middle-class people at leisure. It semes to exhibit Impressionist technique, with great sensitivity to color and light and reduced detail in depicting fabric, faces, and anatomy. Yet notice the firmness of the contour lines. Figures and objects are more sharply delineated than in classic Impressionism.

|

|

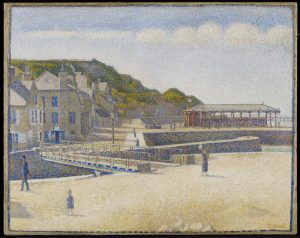

| Seurat, G. (884). Bathers at Asnières. | Georges Seurat. (1888). Port-en-Bessin. |

Seurat’s dual commitment to Impressionist concerns and desire for formal precision led to a remarkable technical innovation. In the mid-1880s, he began to paint by filling a canvas with thousands of tiny dots of color. Remembering the Impressionist principle that nature does not contain contour outlines, his brush never draws a line or curve. Yet dots contrasted against each other create firm contours. They also permit profoundly complex interplays of light and color that emulate the complexity of color in the real world.

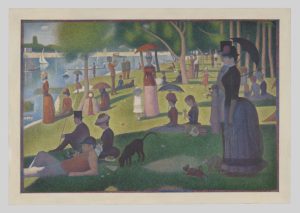

Seurat’s A Sunday on the Grand Jatte accomplishes an extraordinary density of subject, technique, and formal brilliance. The painting is ten feet wide and contains countless dots of color. Yet the whole is composed with precise control. Notice the gentle compositional sweep of the grounds and shadows. And consider the colors playing off against each other: red paired repeatedly with its Complementary Color, green.

|

|

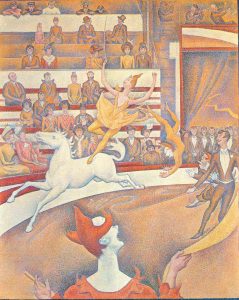

| Georges Seurat G. (1884). A Sunday on La Grande Jatte | Georges Seurat. (1891). Le Cirque (The Circus) |

Seurat’s Le Cirque is another masterpiece of pixilated line. Click the link to magnify the Jstor image and you will see individual dots forming the lines that sweep upward in cheerful optimism. Notice also how the reds and yellows warm the scene and uplift our spirits. Finally think about Seurat’s prescience: his pointillism anticipated the technology of our own day as computer-generated images portray complex figures with hundreds of thousands of pixels.

Vincent van Gogh

Born in the Netherlands, Vincent van Gogh famously sold very few paintings in his life despite having an art dealer for a brother. What he did do was paint. Van Gogh’s early work reflected in a fairly dark style his concern for the working poor. van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters dimly lights the evening meal of peasant farm workers in a dark Palette of earth tones. Figures and fabrics are stylized in organic arcs that suggest the lumpy soil.

|

|

| De Aardappeleters (The Potato Eaters) (1885). Oil on canvas. | The Night Café (June 1890). Oil on canvas. |

In The Potato Eaters, we see an artist already displaying some stylistic freedom in Contour Line. However, after moving to Paris in 1886 and meeting the Impressionists, van Gogh began to develop a more radically liberated vision for his art. This vision centered on color.

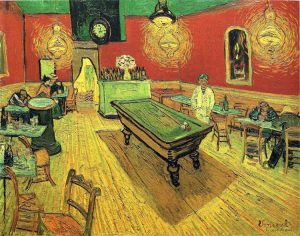

Impressionists achieved magnificent complexity laying one color against another. But they did so to try to capture the interplays of light and object in nature. van Gogh began to envision a different, Expressive role for color. In a letter to Theo, his art dealer brother, Vincent explained a profound shift in commitment: “instead of trying to render exactly what I have before my eyes, I use color more arbitrarily in order to express myself forcefully [emphasis added]” (van Gogh, 18 August, 1888). In another letter to Theo, Vincent explains his Expressive approach to color in The Night Café:

The Night Café was painted in Arles, a town in Provence, France to which van Gogh moved in 1888. van Gogh was dazzled by the quality of the sunlight there and began to produce scores of his greatest compositions. His passion for Provençal sunlight bursts from The Sower in the unearthly gold of the sun-drenched sky. The light plays on brilliantly modulated greys and blues, the soil. And yet, we can ask ourselves, does sunshine really look like that? Are those really the hues we find in clods of earth? The intense gold of the sun and its rays, are thy not excessive, almost ominous?

|

|

| The Sower (Sower with Setting Sun) (1888). Oil on canvas. | The Church at Auvers. (June 1890). Oil on canvas. |

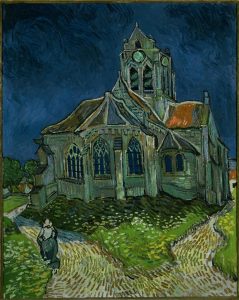

Van Gogh is not precisely linked with Expressionism,[1] but the hypnotic force of his late work seems driven by internal forces. Monet’s distortions of the cathedral reflected atmospheric conditions. Line and Form in van Gogh’s The Church at Auvers are distorted, not by atmospheric conditions, but as by an artist’s liberated brush and an expression of inner turmoil.

[1] Expressionism: a style in art in which naturalism is replaced by exaggerated images to express intense, subjective emotion. Inspired by van Gogh, Gaugin, and Munch, the expressionist movement in painting was centered in Germany from about 1880 to 1905. Expressionism dominated early German cinema and Hollywood film noir in the 1930s (Expressionism).

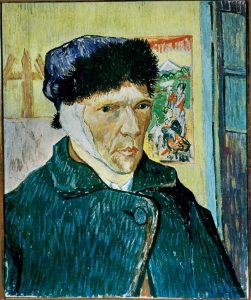

And the fact is that van Gogh suffered from mental illness. The self-portrait below shows bandages covering an ear which, during a manic episode, he lacerated with a razor.

|

|

| Self-portrait with Bandage. (1889). Oil on canvas. | The Starry Night (Saint Rémy). (June 1889). Oil on canvas. |

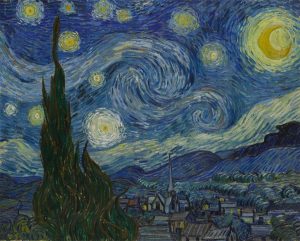

After this incident, van Gogh was institutionalized, though he continued to paint. The Starry Night, one of the world’s most beloved paintings, was composed looking out from his room in the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Cosmic chill hovers over the sleeping town and the looming, sepulchral tree. The sky is contorted into churning vortexes of energy, distant stars pulsing with light. van Gogh’s inner demons express themselves in robust Formal elements—pigments, brushstrokes, compositional balance: a dark vertical shape on the lower left balanced by the luminous moon on the upper right. The dark values of cold, blue hues. The rhythm of repeated, organic whorls.

|

| Wheatfield with Crows. (1890). Oil on canvas. |

In a last burst of creativity before taking his own life with a gunshot, van Gogh embraced the vistas of Provençal fields. The Wheatfield with Crows, teems with menace. Confident brush-strokes project rows of wheat in single bars of color. The skies are haunted by birds dashed off in brisk, angled lines. The rapid technique of the Impressionist here expresses a personal vision dramatically interweaving the light of life with dark agents of doom.

Paul Gauguin and the “Primitive” Ideal

Paul Gauguin was born in Paris but was largely raised in Peru. He returned to France, began an affluent career as a stockbroker, married and sired five children. Then he discovered painting and surrendered his career and his family to a struggling art career.

Gauguin began his career under the influence of the Impressionists, but restlessly began to seek his own road to expression. In the late 1880s, he spent time in an artists’ colony in Brittany. There, he formulated an approach to painting which surrendered Mimetic accuracy in favor of freedom of Expression.

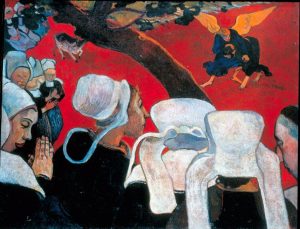

Sitting in church one day, Gauguin was struck by a double vision. He could see the parishioners, mostly women, attending to the sermon. In his mind, he could also see the biblical scene narrated by the preacher: Jacob wrestling with the angel (Genesis 32.22-32).

|

| Jacob Wrestling with the Angel of the Vision After the Sermon. (1888). Oil on canvas. |

Can you delineate the two levels of this vision in the resulting composition? The women are gathered after a church service, presumably outside the church. Stretched out before them, however, is not a typical churchyard. On a field of red, Jacob wrestles with the angel, clearly the subject of the sermon. The ground lies flat at an angle unaligned with the ground which would “realistically” stretch out before the women. Gauguin ignores the rules of Linear Perspective that had governed painting since the time of Bramante and Masaccio. The field of the vision is not Virtual Space, but a projection from the artist’s private visualization.

Can you delineate the two levels of this vision in the resulting composition? The women occupy the foreground. Beyond them stretches the field in which the biblical scene plays out. But this is not a conventional depiction of landscape. It lies flat at an angle unaligned with the ground which would “realistically” stretch out from the standing women. Gauguin ignores the rules of Linear Perspective that had governed painting since the time of Bramante and Masaccio. The field of the vision is not Virtual Space, but a projection from the artist’s private visualization.

The two zones of the composition—the commonplace women and the private vision—are also distinguished by color. The women are portrayed with naturalistic Descriptive Color, black dresses, white, bonnets and relatively normal flesh tones. But the field of the vision is a wholly unnatural red. Gauguin is selecting color here, not because that is what a field outside a church might actually look like, but for its Expression of personal feeling and Signification.

Seeking the Primitive

In the late 19th Century, Europe reached the high point of its colonial domination of the world. As do all oppressing peoples, nations justified their exploitation of other peoples with a myth of cultural superiority. We dominate and enjoy privileges because our civilization is superior. They serve us because they are primitive and unfit for rule or independence.

Yet a backlash against the cultural arrogance of the Euro-American West was coming to life. For Gauguin, it began with a restless repudiation of European civilization which he saw as a disease. Seeking escape, he repeatedly moved in pursuit of the exotic. After stays in Martinique and with van Gogh in Arles, Gauguin moved to Tahiti, the least civilized outpost of the French empire, in 1890.

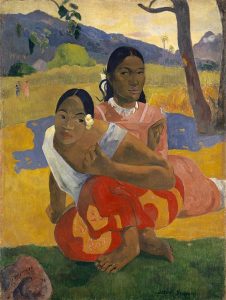

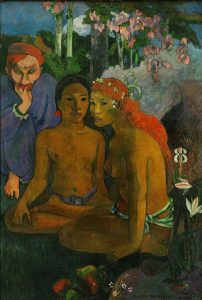

Gauguin embraced Tahitian culture as a liberating, primitive antidote to the civilization he despised. Of course, his colonialist’s fever dream of purity fails to understand that the term primitive is itself a patronizing assumption of cultural superiority and privilege. Gauguin, who struggled to sustain marriage commitments, indulged in predatory relations with young women in his “primitive” paradise. Barbarian Tales testifies to his uneasy sense of moral ambivalence in his dream of the primitive as moral salvation, It locates two young Tahitian women in a dreamscape springing from the internal vision of a leering European voyeur.

|

|

| Nafea Faaipoipo (When Will You Marry?) (1892). Oil on canvas. | Contes barbares (Barbarian Tales). (1902). Oil on canvas. |

Gauguin’s lines and figures have a kind of blocky integrity with little sense of perspectival depth. His colors are often non-natural, frequently nuanced in subtly complex combinations, and always expressive. Gauguin did study Tahitian culture in some depth before allowing it to mix with multiple other cultural forms in compositions which blended colors in complex, expressive tapestries of brushstrokes. The aging, destitute, often sick Gauguin poured his life-long disillusionments into compositions that challenge our visions of life as well as our eyes.

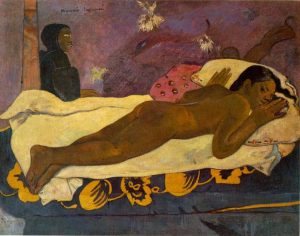

|

|

| Spirit of the Dead Watching. (1892), Oil on canvas. | Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1898). Oil on canvas. |

The Spirit of the Dead Watching assembles archetypal symbols of life, mortality, and spirit around a woman lying upon a bed that in many cultures is the locus of birth, sexuality, and death. Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? fuses a common Tahitian expression—Where are you going? (Brodskaïa, 2018)—with the question that a manifestation of Jesus traditionally asks of Saint Peter seeking to escape Roman persecution: “Quo vadis, where are you going?” These words, universally central to human awareness, are inscribed in the upper left of a composition uniting images of youth, maturity, and age with a suggestive invocation of Asian spirituality. The whole is drenched in subtly interlaid earth tones and cold blues.

Vital Questions

The textbook chronology of European art does not group the Post-Impressionists within the Expressionist tradition that erupted in the early 20th Century. Seurat, van Gogh, and Gauguin challenge the Renaissance Model of painting only to a point. But their compositions of scenes and subjects are significantly altered by the impulse to express their inner selves.

Context

Seurat and Gauguin were Parisians who learned to paint in Paris studios. van Gogh began painting in his native Holland but was transformed by his contact with Impressionist Paris. Seurat and van Gogh remained engaged with Impressionist concerns, though the latter’s move to Arles led to a genuinely rural outlook. The restless Gauguin’s dissatisfactions with French culture led him to a colonialist’s fantasy of primitive life in Tahiti.

Content

Seurat and van Gogh continued to focus on the Impressionist range of subjects, the play of light and color in landscapes, portraits, and, in van Gogh’s case, interior scenes. Like that of the Impressionists, their work foregrounds our awareness of texture and medium.

In van Gogh and Gauguin, however, content takes a definite turn into Expression. Both project their own passions onto the visual subject. Gauguin and, to a lesser degree, van Gogh fill their compositions with symbolic expressions of themes and ideas.

There was, of course, nothing new about expressing ideas in symbols: religious and mythic art had been doing it for millennia. Yet Gauguin and van Gogh each projected privately signifying symbols into their work. Their individual expressionism linked Romantics to the radical individualism of the 20th Century.

Form

Although Seurat, van Gogh, and Gauguin used distinct techniques, each shared a willingness to break down or distort the image. Seurat sought formal precision in his pixelating pointillism while van Gogh and Gauguin began to exercise free flow and independence in their lines, forms, and, especially, their preference for non-naturalistic color. In the Post-Impressionists, formal elements of art are beginning to take precedence over fidelity to the visual subject.

References

Brodskaïa, Nathalia. (2018). Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. New York, NY: Parkstone International. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/betheluniversity-ebooks/reader.action?docID=5343473

Expressionism. (2014). [Article]. Philip’s World Encyclia. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199546091.001.0001/acref-9780199546091-e-3976.

Gauguin, P. (1902). Contes barbares (Barbarian Tales) [Painting]. Essen, DE: Folkwang Museum. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/paul-gauguin/barbarous-tales-1902

Gauguin, P. (1898). D’ou Venons Nous / Que Sommes Nous / Où Allons Nous (Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?). [Painting]. Boston, MA: Museum of Fine Arts, AN SC226475. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/32558/where-do-we-come-from-what-are-we-where-are-we-going?ctx=2c05254d-c16a-4a3a-8d82-eec054004dfa&idx=0

Gauguin, P. (1892). Nafea Faaipoipo (When Will You Marry?) [Painting]. Private collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/paul-gauguin/when-are-you-getting-married-1892

Gauguin, P. (1892). Spirit of the Dead Watching [Painting]. Buffalo, NY: Knox Art Gallery. https://buffaloakg.org/artworks/19651-mana%C3%B2-tupapa%C3%BA-spirit-dead-watching

Gauguin, P. (1898). Vision after the Sermon [Painting]. Edinburgh, Scotland: National Galleries of Scotland. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/artists/paul-gauguin

The Night Cafe, 1888 by Vincent Van Gogh [Article]. (2009). Vincent van Gogh: Paintings, Quotes, and Biography. https://www.vincentvangogh.org/the-night-cafe.jsp

Seurat, G. (1884). Bathers at Asnières [Painting]. London, UK: The National Gallery, London. AN NG3908 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/georges-seurat-bathers-at-asnieres

Seurat, G. (1891). Le Cirque [The Circus]. [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/le-cirque-542

Seurat, G. (1888). Port-en-Bessin. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1272/port-en-bessin-georges-seurat

Seurat, G. (1884). A Sunday on La Grande Jatte [Painting]. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago. Rf 1926.224. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/27992/a-sunday-on-la-grande-jatte-1884

van Gogh, V. (1885). De Aardappeleters (The Potato Eaters) [Painting]. Amsterdam, NL: Van Gogh Museum. https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/search?q=Potato+Eaters

van Gogh, V. (1889). La Chambre de Van Gogh à Arles [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/la-chambre-de-van-gogh-arles-746

van Gogh, V. (June 1890). The Church at Auvers [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/leglise-dauvers-sur-oise-vue-du-chevet-755

van Gogh, V. (June 1890). The Night Café [Painting]. New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/12507

van Gogh, V. (18 August, 1888). Letter to Theo van Gogh. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Van Gogh Museum. http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let663/letter.html#translation

van Gogh, V. (1889). Self-portrait with Bandage [Painting]. London, UK: Courauld Gallery. https://gallerycollections.courtauld.ac.uk/object-p-1948-sc-175

van Gogh, V. (1888). The Sower (Sower with Setting Sun) [Painting]. Otterlo, NL: Kröller-Müller Museum. https://krollermuller.nl/en/vincent-van-gogh-the-sower

van Gogh, V. (1889). De sterrennacht (The Starry Night at Saint Rémy) [Painting]. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, United States. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/vincent-van-gogh-the-starry-night-1889/

van Gogh, V. (1890). Wheatfield with Crows [Painting]. Amsterdam, NL: Rijksmuseum. SID 18118473. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/object/Wheatfield–8ea35a6f35721839ca3e3375f1b7748c

a loose term for the generation of artists who followed the Impressionists and carried their techniques forward into Expression

the conventional values and expectations of painting that derived from the Renaissance tradition: a conception of painting as a window on the world projecting visual space with foreshortening, linear perspective, and accurate mimesis

the dimension of an artistic experience that appeals to or challenges an au-dience’s sense of taste and experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A response distinct from “interested” concerns such as ideology, sexuality, social conflict or economics

the material projected by art for the reader’s mind and imagination. Content can consist of an immediate Subject—e.g. a figure in a painting or a story in a narrative—and Signification, a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature

a late 19th Century dissident movement among French artists that challenged the conventions of academic art. Impressionists painted quickly, outside in the plein air, seeking to capture with a few deft strokes the colors, lighting and atmosphere of the scene—their subjective impression rather than the “real thing.”

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

in visual art, a 2-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth. Line may be straight or curved, directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc

a technique of representation that seeks to capture, not the “real thing,” but rather one’s subjective experience of the subject

a hue which creates an enhanced aesthetic resonance when placed against its opposite on the color wheel: e.g. red with green, yellow with violet, etc.

a particular array of colors strategically selected for an individual composition to achieve an emotional, thematic, or aesthetic effect. A term derived from an artist’s decision about the colors to add to a palette for a particular session.

the boundary line that defines a shape or form in a visual composition. A contour line can be directly drawn or achieved merely through contrast be-tween the colors of the subject and the background.

a dimension of visual art that projects the artist’s inner vision outward, often distorting the subject in “unrealistic” ways

in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any subject or signification: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

color schemes selected to accurately match the “naturalistic” hues of the visual subject as we might see it “in reality”

content in art that projects the artist’s inner vision outward, often distorting the subject in “unrealistic” ways

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

committed to the late 18th and 19th Century reaction against Neo-Classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom.