9.3 The Romantic Rebellion

What do you think?

- Rules. Reason. Ancient lore.

- The wisdom of the heart.

Which reflects your instinctive path to good judgment? If you reflexively turn away from dusty pontification of long dead seers and hew to your heart’s true north, you are a child of the rebellion against Classicism that became Romanticism.

In several European languages, a romance is a prose narrative, that is, a novel. For linguists, Romance languages descend from Latin. In popular English, the word romance denotes passionate love and romantic designates conditions leading to it. But in cultural history, High Romanticism was more, a rebellion against Neo-Classical Reason.

During the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, artists and thinkers began to push back against the idea that wisdom is to be found solely in Reason and Classical tradition. The Romantic Era was …

Delacroix: Formal Rebel

Eugène Delacroix had little trouble being accepted by the academy. His skills in drawing, perspective, and Illusionism were as good as anyone’s. He didn’t necessarily set up as a revolutionary. Yet his formal challenges to Neo-Classical rules opened a world of possibilities to the rebels who followed him.

In his letter to Peisse, Delacroix challenged the restrictions of Neo-Classical taste. He embraced curving, sweeping lines and flamboyant colors. His Battle of Taillebourg took on a topic preferred by the academies: a historical scene. But the composition swirls with dramatic energy, lit with Baroque theatricality. Figures are composed in a vast X centered on a heroic horse. Linear Perspective is minimal and there is little effort to establish zones of Virtual Space. Romantic action bursts from the Picture Pane, unrestrained by Reason.

|

|

|

| Battle of Taillebourg (1837). Oil on canvas. | Lion Hunt. (1855). Oil on canvas. | Liberty Leading the People (July 28th 1830) (1830). Oil on canvas. |

Delacroix traveled extensively in the French colonies of Northern Africa. He helped to establish the romantic image of the “Oriental” people of the region as exotic, mysterious voluptuaries, a stereotype which would haunt Arab peoples until at least the late 20th Century. His Lion Hunt swirls with menacing energy, dominated by contour lines in sweeping, organic curves. Again, light and color flash out of the image, dominated by hot reds and yellows. As in the battle scene, the composition focuses our vision on the crux of an X, a dramatic spotlighted horse and rider lit.

In 1830, the French people arose in the July Revolution against the Bourbon monarchy which had followed the fall of Napoleon. Delacroix celebrated the uprising in a composition which has inspired France ever since. compare the dramatic passion of his treatment with the cool restraint of David’s Death of Marat. In Delacroix’s vision, that red flag, passionate symbol of the people’s rebellion against wealth’s corruption, bursts out of the gloom like an inspiring rocket.

Blake’s Tormented Visions

William Blake was an obscure London printer who composed feverish images and poems protesting what he saw as the sterility and destruction of the age’s hyperrational pragmatism. The most radical of English Romantic voices, Blake developed a “highly distinctive mystic vision” and “personal mythology” which struggled to break free of the past: “years later (in Jerusalem) he was to state … ‘I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Man’s’” (Blake, William, 2012).

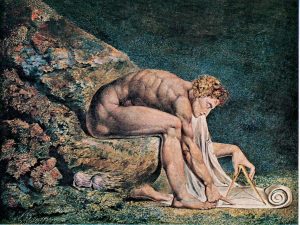

Blake’s brooding sense of oppression centered especially on two giant cultural figures who, he thought, were strangling the inner life of humanity: John Milton, 17th Century author of the great Paradise Lost, and Isaac Newton. Blake was troubled by a theory which appeared to reduce the universe to mathematical formulas. Look again at his Newton. Blake portrays the great physicist as a hunched pedant, striving to measure the cosmos with a diminutive calipers while being dwarfed by a looming rock and a measureless deep space.

|

|

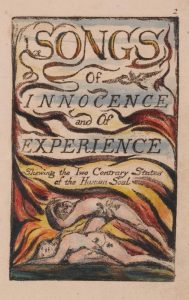

| William Blake. (1795). Newton. Color print with watercolor finish. | Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Plate 2. (1789 to 1794). Etching. |

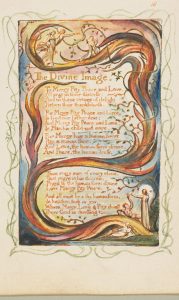

Almost completely unknown to the cultural elites of London, Blake printed his own compositions in fusions of image and text. His Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794) compiled brief lyrics which opposed sunny visions of ideal life with the darker harvest of tragic experience. Compare his contrasting visions of the notion that human beings reflect the divine image.

The Divine Image. Songs of Innocence.

To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

All pray in their distress;

And to these virtues of delight

Return their thankfulness.For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is God, our father dear,

And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is Man, his child and care.For Mercy has a human heart,

Pity a human face,

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.Then every man, of every clime,

That prays in his distress,

Prays to the human form divine,

Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace.And all must love the human form,

In heathen, Turk, or Jew;

Where Mercy, Love, and Pity dwell

There God is dwelling too.

|

| Songs of Innocence: The Divine Image. Plate 18. |

A Divine Image. Songs of Experience

Cruelty has a Human Heart

And Jealousy a Human Face

Terror the Human Form Divine

And Secrecy, the Human DressThe Human Dress, is forged Iron

The Human Form, a fiery Forge.

The Human Face, a Furnace seal’d

The Human Heart, its hungry Gorge.

Blake, whose achievement was only belatedly recognized, fired among the first reactionary shots against hyper-rational Classicism. He furiously opposed his personal imagination to the rules of Neo-Classicism. He rejected the linear certainties of rationalism and embraced the tension between light and dark forces in nature and the human heart. He personally embodied High Romanticism:

“Horror, melancholy, or sentimentality”: hmmm. Sounds like an apt formula for today’s blockbuster cinema, graphic novels, and video games. Are we still living in the Romantic era?

Wordsworth: Nature and the Imagination

Have you ever chafed at a classroom expectation that you read ponderous texts written long ago by dead wizards who make no sense to you? (I mean, not in this class, right?) If so, you may appreciate a poetic dialogue in which William Wordsworth’s Persona responds to a friend who had been chiding him about wasting too much time exploring the woods and failing to devote enough time to study.

William Wordsworth, “The Tables Turned; An Evening -Scene, On The Same Subject”

Up ! up ! my friend, and clear your looks.

Why all this toil and trouble ?

Up ! up ! my friend, and quit your books,

Or surely you’ll grow double.

The sun above the mountain’s head,

A freshening luster mellow,

Through all the long green fields has spread.

His first sweet evening yellow.

Books! ’tis a dull and endless strife,

Come, hear the woodland linnet, in

How sweet his music; on my life

There’s more of wisdom in it.

And hark! how blithe the throstle sings!

And he is no mean preacher;

Come forth into the light of things,

Let Nature be your teacher.

She has a world of ready wealth,

Our minds and hearts to bless

Spontaneous wisdom breathed by health,

Truth breathed by cheerfulness.

One impulse from a vernal wood

May teach you more of man;

Of moral evil and of good.

Than all the sages can.

Sweet is the lore which nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Misshapes the beauteous forms of things;

We murder to dissect.

Enough of Science and of Art;

Close up these barren leaves

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.

|

| William Shuter. (1798). Portrait of William Wordsworth. Oil on canvas. |

William Wordsworth championed the Romantic rebellion in English verse because he loved nature. I mean, he really loved Nature (capital N!). This champion of the individual imagination lived most of his life in the English Lake District. In his day, Cumbria was an isolated, neglected rural region. Yet Wordsworth tramped across its fells for a lifetime, watching and listening to what he saw as a natural wisdom that could inspire in ways dusty books could not. He virtually invented the tourist industry in the region, and today tens of thousands of travelers from near and far flock to the Lake District each year.

William Wordsworth (1798). I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

This perhaps all too famous lyric encapsulates the Romantic vision of wisdom. One finds it, not in dusty tomes, but in the heart’s response to Nature:

Close up these barren leaves

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.

Well, there you are, the Romantic Era in a nutshell. Notice the themes compressed in these four lines:

- A suspicion of academic and scientific lore

- A reliance upon one’s own sense of truth

- A conviction that the individual’s heart channels wisdom

- A resolution to “go out” to encounter the world, especially of nature

In 1798, Wordsworth edited the Lyrical Ballads, a collection of lyrics written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Wordsworth, and others. At the time, “literary” poetry was expected to emulate classical models such as the ode or the elegy and to express exalted themes in grandiose language. Ballads, i.e. narrative folk songs of the common people, were dismissed as crude, unserious, unworthy of serious poetic attention.

The title of Wordsworth’s collection challenged everyone’s idea of what poetry can be. The Preface acknowledges something you might well have felt: readers of poetry often must “struggle with feelings of strangeness and awkwardness” when confronted with stilted, archaic language.

The principal object [of these poems]… was to choose incidents and situations from common life, and to relate or describe them… in a selection of language really used by men,[1] and, at the same time, to throw over them a certain coloring of imagination, whereby ordinary things should be presented to the mind … in a state of excitement.

Humble and rustic life was generally chosen, because, in that condition, the essential passions of the heart find a better soil … and speak a plainer and more emphatic language. …

For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings[2] (Wordsworth, Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, 1800).

[1] Italics added by your editor. Sadly, the language of the day tended to forget that women deserved to be mentioned.

[2] Again, italics added. This definition of poetry became a rallying cry of the age. Yet the claim that all good poetry is a spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings very questionable and speaks for a Romantic perspective by no means shared universally.

Whether or not you are taken with early 19th Century poetry, your cultural heritage has been shaped by Wordsworth’s manifesto. Its principles today may seem so conventional that we may struggle to see how revolutionary they were:

- The experience of humble, working class people is worthy of art and poetry.

- Verse that draws on the language of everyday life can have a powerful impact.

- Poetry reflects on passions found in the individual heart.

- Great poetry breaks conventional rules to express the individual poet’s imagination.

Rosetti’s Private Vision

Daughter of Italian immigrants in London, Christina Rossetti channeled an age-old religious and cultural heritage. Closely associated with the artists of the self-proclaimed Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, she focused her creative energies on verse. She lived a quiet life of devotional discipline. And she composed a rich treasury of lyrics steeped in a deeply Romantic inward vision.

Psalm 130 begins with an anguished cry to the Lord:

Lord, hear my voice.

Let your ears be attentive

to my cry for mercy.

In the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible, the first words are De Profundis. Through the centuries, this phrase has been used to orient the most agonized outcries of human distress. Here is Rossetti’s version.

Christina Rossetti. (1881) De Profundis

Oh why is heaven built so far,

Oh why is earth set so remote?

I cannot reach the nearest star

That hangs afloat.

I would not care to reach the moon,

One round monotonous of change;

Yet even she repeats her tune

Beyond my range.

I never watch the scatter’d fire

Of stars, or sun’s far-trailing train,

But all my heart is one desire,

And all in vain:

For I am bound with fleshly bands,

Joy, beauty, lie beyond my scope;

I strain my heart, I stretch my hands,

And catch at hope.

One can read these lines in various ways, obviously including the way of spiritual devotion. One can also recognize in it the essential Romantic quest for inward illumination. Compare the opening lines of Blake’s Auguries of Innocence (c 1803):

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

Rossetti’s association with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of painters heightened her awareness of the artistic process in another medium. See if you can recognize the Romantic threads in her view of the painter’s imagination.

Christina Rossetti. (1856), In an Artist’s Studio.

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel — every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more or less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

Vital Questions

Context

Do you shy instinctively away from poetry? If so, I’ll bet that your concerns reflect the assumptions about what poetry is that Wordsworth explores in the Preface. And I’ll bet that many of your concerns would fade away facing poems that speak plainly about the experiences of real people. Don’t we all respond to the language of people speaking to people? Isn’t that what the poetry in pop songs does so well?

Content

Artists and poets have of course pioneered and clashed over many a road since 1800. But in one sense, Wordsworth’s Romantic model has won the day. Since then, the vision of an individual artist has dominated our sense of great artistic achievement. Art has widely embraced the life of ordinary people. Poets, song writers, novelists, artists, film makers and dramatists freely engage everyday life without apology.

Furthermore, the Romantic quest of Blake, Wordsworth, and Rossetti continues to drive our sense of artistic richness. In countless ways and forms, it seeks what, in his 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech the American novelist William Faulkner called the only proper subject of art: “the human heart in conflict with itself”–a distinctly Romantic conception of what art is about.

Form

Wordsworth’s Preface laid out a formal vision that would lead poets on a long road away from artificiality and pedantry. The language of people speaking to people. It would take some time for literary poetry to fully engage the language of real life, but from contemporary literary verse to hip hop, poets have followed the lead he articulated in his famous Preface.

References

Blake, William. (1794). The Ancient of Days. Frontispiece. Europe, a Prophecy (1794) [Relief etching with watercolor]. Private Collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/william-blake/the-ancient-of-days-1794

Blake, W. (c 1803). Auguries of Innocence [Poem]. Poetry Foundation https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auguries_of_Innocence

Blake, W. (1795). Newton Illustrating Plate. Nebuchadnezzar . London: UK: Tate Modern Museum https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/blake-newton-n05058

Blake, W. (18). Songs of Experience: A Divine Image [Poem]. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45953/a-divine-image

Blake, W. (1789 to 1794). The Divine Image. Songs of Innocence: . Plate 18. [Etching]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/347927

Blake, W. (18). Songs of Innocence: The Divine Image [Poem]. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43656/the-divine-image

Blake, William. (1789 to 1794). Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Plate 2, Combined Title Page [Relief etching with watercolor]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/892559

Blake, William. (2012). [Article]. Birch, D., & Hooper, K. [Eds.]. The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-842.

Briefel, Aviva. (2006). Rossetti, Christina [Article]. Oxford, UK: The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780195169218.001.0001/acref-9780195169218-e-0407?rskey=BWGrzh&result=4

Delacroix, E. (15 July, 1849). Letter to Léon Peisse. P. 289. Stewart, J. (Trans. Ed.). Eugéne Delacroix: Selected Letters, 1813-1863. p. 289. London, UK: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1954. Internet Archive Selected letters, 1813-1863; : Delacroix, Eugène, 1798-1863 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Delacroix, E. (1837). The Battle of Taillebourg [Painting]. Versailles, FR: Musée Historique. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-delacroix/the-battle-of-taillebourg-draft-1835

Delacroix, E. (1830). Liberty Leading the People (July 28th 1830) [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. RF129 https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065872

Delacroix, Eugène. (1855). Lion Hunt [Painting]. Stockholm, SW: National Museum of Sweden. https://collection.nationalmuseum.se/en/collection/item/23399/

Romanticism [Article]. (2015). In C. Baldick (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198715443.001.0001/acref-9780198715443-e-131

Rossetti, C. (1881), De Profundis. A Pageant and Other Poems. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44994/de-profundis

Rossetti, C. (1856), In an Artist’s Studio [Poem]. In Rossetti, W. M. (Trans.) New Poems by Christina Rossetti. (1896). New York: MacMillan. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/146804/in-an-artist39s-studio

Shuter, William. (1798). Portrait of William Wordsworth [Painting]. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Library. https://rare.library.cornell.edu/the-cornell-wordsworth-collection/

Wordsworth, W. (1800). “The Tables Turned.” In Lyrical Ballads. Bartleby https://www.bartleby.com/333/494.html.

Wordsworth, W. (1800). Preface. Lyrical Ballads. London: N. Longman And O. Rees. https://www.bartleby.com/39/36.html.

Wordsworth, William. (2009). [Article]. In Birch, D. (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780192806871.001.0001/acref-9780192806871-e-8208.

often contrasted with “romantic” folk traditions, an aesthetic associated with a social elite and a venerated past, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Characterized by clarity, order, balance, symmetry, reason, mathematical precision

A) a reaction against Neo-Classical Reason that seeks to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom. B) as an aesthetic, a rejection of strict artistic rules and convention in favor of organic form and innovation. C) often, advocacy for folk traditions that have been despised by classical elites

a style of art that emulates a former classical age, generally emphasizing conventional rules, mathematical precision, and reason over passion

the 17th Century artistic tradition that followed the Renaissance, characterized by gritty social realism, dramatic action, depth of characterization, closed compositions, and intense contrasts between light and shadow. More broadly, any art emulating the values of the Baroque

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

the virtual window glass through which the 2-dimensional surface of a painting’s Medium—fresco, canvas, panel—"looks out” into a projected space

art that seeks to recover the values and techniques of a classical past, generally emphasizing conventional rules, mathematical precision, and reason over passion. Dominant in Europe during the 18th and early 19th Centuries.

committed to the late 18th and 19th Century reaction against Neo-Classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom.

a poem or song that tells a story. Traditionally, oral poetic genres compiled anonymously within folklore traditions for audiences with limited literary education