9.2 a Dream of Classical Peace

Imagine yourself living in early 18th Century Europe. The last century has mercifully come to an end. Wars, civil wars, and brutal suppressions of dissidents have killed hundreds of thousands of people, driven in large part by endless, divisive culture wars over religion. You might yearn for a bit of peace and quiet.

The 18th Century is known as the period of the Enlightenment. Philosophers and theoreticians tried to tamp down the chaos of passionate conflict and apply reason to contentious issues. Social theoreticians like John Locke and Thomas Hobbes brought rational rigor to bear on social issues. Adam Smith analyzed economic dynamics. Mary Wollstonecraft challenged traditional gender roles with reasoned argument.

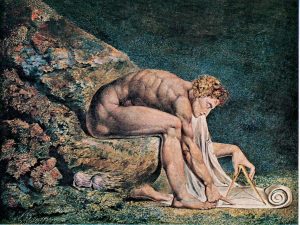

|

| William Blake. (1795). Newton. Color print with watercolor finish. |

Few Enlightenment achievements matched the impact of Isaac Newton’s mathematical model of the heavens. Like everyone else in Christendom, Dante had assumed that the stars in space were “heavenly bodies,” visual portals into God’s abode, their motions controlled by the force of God’s love. Newton offered an astronomical model that rationally accounted for what we observe with mathematically precise “laws of physics.” From this point forward, the heavens would be conceptualized, not theologically, but empirically. Blake pictures Newton bringing a geometrician’s calipers to the plans of the universe.

If one could master the mystery of the heavens with mathematics, then, it seemed, Reason—note the capital letter!—could blunt the force of chaotic passions and bring order to society. Naturally enough, European Reason-oriented thinkers and artists turned for guidance to the Classical tradition.

Pope’s Rules for Art

No, not the Papal head of the Roman Church, but Alexander Pope, an English poet who helped articulate the core values of Neo-Classicism. Let’s peek into his Essay on Criticism (1711).

from An Essay on Criticism, Part 1

‘Tis with our judgments as our watches, none

Go just alike, yet each believes his own.

In poets as true genius is but rare,

True taste as seldom is the critic’s share;

Both must alike from Heav’n derive their light,

These born to judge, as well as those to write. …

Most have the seeds of judgment in their mind;

Nature affords at least a glimmering light;

The lines, though touched but faintly, are drawn right.

But as the slightest sketch, if justly traced,

Is by ill coloring but the more disgraced,

So by false learning is good sense defaced;

Pope addresses the challenge of good taste: no one agrees on what it is, but all believe they have it. He argues that everyone has a bit of good sense in evaluating art, but most lose their way by “false learning.”

OK, wait. If everyone disagrees on taste, how can some be preferred? In the 18th Century, published critics proliferated, disputing the virtues and vices of art with the fervor that used to be dominated by theological wrangling. Instinctively, people were yearning for sets of standards which could make sense of the world, including the world of the arts. Pope has much to say about true (!?) criticism let’s just note two core values.

By her just standard, which is still the same:

Unerring Nature, still divinely bright,

One clear, unchanged, and universal light,

Life, force, and beauty, must to all impart,

At once the source, and end, and test of art.

Art from that fund each just supply provides,

Works without show, and without pomp presides:

In some fair body thus th’ informing soul

With spirits feeds, with vigor fills the whole,

Each motion guides, and every nerve sustains;

Itself unseen, but in th’ effects, remains.

Pope assures us that we can count on one guide, NATURE, which avoids the stylistic excesses of strident schools of art. If you feel that a poet or artist or filmmaker is “over the top,” you might be reassured.

But what does Pope mean by NATURE? How will we recognize or emulate it? Can you guess his answer?

Those RULES of old discovered, not devised,

Are Nature still, but Nature methodized;

Nature, like liberty, is but restrained

By the same laws which first herself ordained.

Hear how learned Greece her useful rules indites,

When to repress, and when indulge our flights:

High on Parnassus’[1] top her sons she showed,

And pointed out those arduous paths they trod;

Held from afar, aloft, th’ immortal prize,

And urged the rest by equal steps to rise.

Just precepts thus from great examples giv’n,

She drew from them what they derive from Heav’n.

The gen’rous critic fanned the poet’s fire,

And taught the world with reason to admire.

[1] Parnassus: Mount Parnassus was the location of the oracle of Delphi which ancient Greeks would consult to receive, as they thought, the direct advice of Apollo, the God of Wisdom.

And there we have the Neo-Classical formula: as did the Renaissance Humanists, learn the rules from the Classical Greeks and apply them with restraint through Reason. At this point, let’s notice something. Pope not only articulates rules for good poetry, he also exemplifies it. His “essay” is composed in Heroic Couplets, an English verse form associated with translations of Classical epics. He expresses reasoned arguments with elegant wit and irony, not passion and bombast.

You keep thinking we are done with those Classical Greeks, but they keep popping up, don’t they?

Neo-Classical Painting: Elegant Restraint

We have not discussed an entire epoch in European painting: the Rococo. That’s OK, but we need the smallest feel for what the Neo-Classical painters reacted against. The Rococo was a time of vastly wealthy aristocrats covering their palatial homes with extravagant art. Rococo artists pushed Renaissance and Baroque styles and techniques to their limit, but always in pursuit of pleasure. Fragonard’s depiction of Happy Lovers portrays an insipid concept of love in bright, high value colors, an adolescent overdoing the makeup.

|

|

| Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Happy Lovers. (c 1765). Oil on canvas. | Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. (1813). Betrothal of Raphael and the Niece of Cardinal Bibbiena. Oil on paper mounted on canvas |

This is the sort of overelaborated style that Pope was complaining about. By contrast, Ingres tones down the silly emotionalism and applies Baroque composition, lighting, and color to a sober dramatization of the Renaissance master Raphael’s engagement ceremony.

Today, Jacque-Louis David is cited as the master of Neo-Classical painting. Early on, he frequently composed tributes to civic responsibility. Socrates, the mentor for the Greek philosopher Plato, was condemned to death by reactionary citizens who thought his ideas were corrupting the youth of Athens. David portrays him choosing to obey the corrupt verdict even though his followers are offering him an escape route.

|

|

| The Death of Socrates. (1787). Oil on canvas. | The Oath of the Horatii. (1784). Oil on canvas. |

Search for Neo-Classical painting and The Oath of the Horatii will pop up. It refers to an incident in early Roman history when the men in a family went off to war for the honor of the state. The men resolve to follow the dictates of dutiful Reason; the women huddle in a corner, wracked with anxiety over the cost of war.

David’s composition recalls the Renaissance. Architectural lines form meticulous Linear Perspective and define zones of receding Virtual Space. Both groups of figures are composed in firm triangular groupings and the colors are muted grays, browns and beiges. Emotional restraint. Formal restraint. Classically inspired Reason.

Classically Inspired Revolutions

When we think of Classicism, we normally think of conservative affirmations of a society and its orders of privilege. In the late 18th Century, however, enormous social upheavals and inconceivably wide gaps in wealth were undermining the authority of what the French called le ancien régime. Revolutions erupted in the British colonies of America and in France. Both resulted in democratically conceived republics.

In both cases, the quest for legitimacy led to an embrace of Neo-Classical art. On the one hand, both revolutions were inspired by political theorists who looked back to the democracy of Athens and the Republic of Rome. Without realizing it, they also looked to the institutions of the Iroquois alliance in the United States and Canada. But the emphasis was on Classical heritage.

On the other hand, Neo-Classical art allowed the new regimes to confer on themselves the gravitas of ancient ages. It is no accident that architecture in France and Washington D.C. resembled that of ancient Athens. And consider the sculptures of George Washington as a Classical Greek law-giver.

|

|

| Giuseppe Ceracchi. (1795). George Washington. Marble. | Horatio Greenough. (1840). George Washington. U. S. Capital Rotunda. |

David: The Classical Revolutionary

In France, Jacques-Louis David was an early supporter of the Revolution of 1798. His Death of Marat mourns the murder of Jean-Paul Marat, a radical journalist whose enormous influence drove the Revolution to extremes during the so-called Reign of Terror which condemned thousands of people to the guillotine. Marat was stabbed in his bath by a woman who felt that she was resisting the terror.

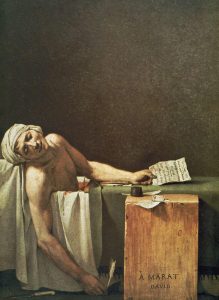

|

|

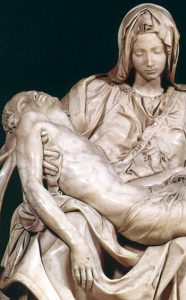

| Death of Marat (1793). Oil on canvas. | Michelangelo. (1498-1500). Pietà. Detail. |

David treats Marat as a revolutionary martyr. Compare the resemblance between the slumping arms of Marat and Christ in Michelangelo’s Pietá. Yet his composition restrains itself with Neo-Classical rigor. Colors are muted. Sheets and cabinet align in a verticality that stabilizes the predominant horizontals. Light graces Marat’s face but without the dramatic contrasts of a Caravaggio. Devotion, but not exuberant passion.

The social instabilities of the Revolution eventually led to Napoleon Buonaparte’s ascendancy to Imperial power. Napoleon backed the Revolution, won some battles in resulting wars, and transformed the Republic into a basis for the conquest of much of Europe.

|

|

| Napoleon Crossing the Saint Bernhard Pass. (1802). Oil on canvas. | The Coronation of Napoleon and Josephine. (1807). Oil on canvas. |

David’s classical restraint evolved into extravagant boosterism for the new regime. His adoring and not particularly realistic image of Napoleon on campaign recalls the heroic equestrian statues of Renaissance heroes. His sumptuous panorama of the coronation in which Napoleon forced a reluctant Pope to bless his conquests resembles Raphael’s celebration of the Christian Emperor Constantine.

Academic Art

Usually, rules of Style rules are invoked primarily by example. During the 18th Century, however, European academies of art articulated them. In Paris, the Académie des Beaux-Artes organized the process of mentorship and training. They articulated rules by which fine art should be assessed:

Academism preserved familiar classical forms and brought them to the level of an immutable law, to the denial of the artist’s individuality— he[1] was only supposed to imitate his great predecessors. … The Academy determined how the picture was to be drawn, including the general style (neoclassical was preferred), recommended color schemes, correct brush strokes and much more.

The work was obliged to carry an intellectual load, [drawing on] literature, religion and mythology, … ancient works and … historical and legendary characters. The picture also was to contain uplifting morality, telling the viewer about the eternal truths and ideals.

Artists idealized their subjects, used realistic colors, … built an impeccable linear perspective and did not dare to experiment: … they should clearly correspond to the chosen historical era (Bahmat, 2020).

[1] Or, of course, she.

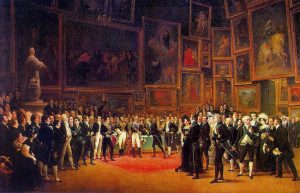

These Neo-Classical values became the basis for assessments which determined artists’ careers. Each year, artists would submit works to the academy for review in a competition for inclusion in a salon, or select showing. Artists and works that made the cut gained market value; those which did not were stamped Refused, a blow to the artists’ careers.

|

| François Heim. (1827). Charles X Distributing Awards to Artists Exhibiting at the Salon of 1824 at the Louvre (January 15th 1825). Oil on canvas. |

Academic rules of assessment addressed not only technique, but also subject matter:

To regulate French painting, the Academy introduced the hierarchy of genres, … ranked in accordance with so-called edifying value: …

— paintings on historical subjects

— portraits

— genre painting

— landscapes

— still life

This system was the basis for awarding scholarships and prizes, as well as distributing the hanging places in the Salon. In addition, the chosen genre influenced the cost of the work (Bahmat, 2020).

Did you get that? No matter how well you paint it, a landscape will be judged inferior to a portrait which in turn cannot match the value of a historical narrative. Can you imagine an era as rule-bound as this?

Vital Questions

Context

So let’s return to the chapter’s first question: should an artist focus on following the rules of convention? Or should she gleefully break the rules in the name of innovation? The Neo-Classical era challenged artists to submit themselves to the rules.

Content

The hierarchy of genres pressured artists to focus on conventional topics and themes from the Christian and Classical traditions. Academic rules strongly preferred Reason and irony over passion and ideological extremism. It is worth noting their emphasis on elite levels of society.

Form

Strict rules of form strove to perfect the principles of Representation and Composition inherited from the Renaissance. In painting, special emphasis was placed on precisely accurate drawing and linear perspective leading to Illusionism. Yet, as in Classical Greek art, scenes and figures were idealized, smoothed out, flaws edited out. The goal was to produce a gleaming illusion of a scene perfectly embodying the finest themes and ideas.

Rules and traditional perfection. Can you imagine what is coming? You guessed it: reaction, even rebellion. Neo-Classical values laid down a baseline which would be challenged by three centuries of reactive turmoil.

References

Bahmat, E. (July 3, 2020). Academism. Arthive Encyclopedia. https://arthive.com/encyclopedia/4239~Academism

Blake, W. (1795). Newton [Color print]. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.11674932

Ceracchi, Giuseppe. (1795). George Washington [Sculpture]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 14.58.235. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/192901

David, J. L. (1807). The Coronation of Napoleon and Josephine [Painting]. Paris, Fr: Musée du Louvre. AN 3699. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010066648

David, Jacques Louis. (1793). Death of Marat [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. RF 1945 2. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010059773

David, J. L. (1787). The Death of Socrates [Painting]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. AN 436105. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436105

David, Jacques-Louis. (1801-1802). Napoleon Crossing the Saint Bernhard Pass. [Painting]. Versailles, FR: Chateau de Versaille. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/jacques-louis-david/napoleoncrossing-the-alps-at-the-st-bernard-pass-20th-may-1800-1801

David, Jacques-Louis. (1784). The Oath of the Horatii [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre, ID ART147619. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010062239

Fragonard, Jean-Honoré. (c 1765). Happy Lovers [Painting]. Pasadena, CA: Norton Simon Museum of Art. https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/F.1965.1.021.P

Greenough, Horatio. (1840). George Washington [Sculpture]. Washinton D.C.: U.S. Capital Rotunda. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.30501767

Heim, F J. (1827). Charles X Distributing Awards to Artists Exhibiting at the Salon of 1824 at the Louvre. January 15th 1825 [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. INV 5313; C 245. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065951

Ingres, J-A-D. (1813). The Betrothal of Raphael and the Niece of Cardinal Bibbiena [Painting]. Baltimore, MD: Walters Art Museum. https://art.thewalters.org/object/37.13/

Michelangelo. (1498-1500). Pietà [Statue]. Vatican: St. Peter’s Basilica. https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/eventi-e-novita/iniziative/Eventi/2022/tre-pieta-di-michelangelo.html

Pope, A. (1711). An Essay on Criticism. Part I. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44896/an-essay-on-criticism-part-1

a style of art that emulates a former classical age, generally emphasizing conventional rules, mathematical precision, and reason over passion

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

an English verse form associated with 18th Century translations of classical epics. It accommodates long, flowing passages with rhymed pairs of lines that avoid breaking down into stanzas. The meter is iambic pentameter.

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

often contrasted with “romantic” folk traditions, an aesthetic associated with a social elite and a venerated past, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Characterized by clarity, order, balance, symmetry, reason, mathematical precision

a consistent pattern of choices regarding form and technique that comprise an identity for an artistic tradition, movement, or individual vision

a standard feature of art in a given genre that is expected and understood in the context of origin: e.g. a content, a style, a signification, a theme

a particular type of composition marked by expected, conventional features: e.g. Japanese haiku, Chinese landscape painting, Renaissance sonnet

an often wryly humorous, indirect mode of communication that asks the reader to compare what is said with some known or signified reference. Frequently used to puncture false pretentions, especially of the social elite. E.g. a standup comedian who relies on the audience to draw on what it knows about a celebrity to get the joke.

a function of visual art which seeks to emulate a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate im-ages and actions in time and space

the conviction that a painting or sculpture’s most important task is to imitate the appearance of nature as naturalistically as possible