8.5 Metaphysical Figures

Metaphysical Figures? Oh, yeah. Another one of those poems that make no sense whatsoever. English teachers love these. I just get lost.

Ever feel that way? It’s true. Some poets are harder to read than others. And it isn’t only college students who get put off. The great 18th Century critic Dr. Samuel Johnson assessed poets’ work with a levelheaded appreciation for good sense. He was particularly irritated by a style of verse that flourished in the previous century. He dubbed the purveyors of this Style the metaphysical poets:

The most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together; nature and art are ransacked for illustrations, comparisons, and allusions; their learning instructs, and their subtilty[1] surprises; but … though [readers] sometimes admire, they are seldom pleased (Johnson).

[1] Subtilty: 18th Century spelling of subtlety

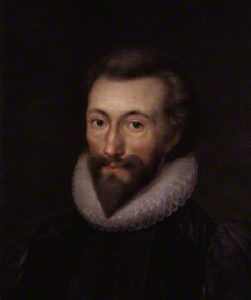

For Johnson, one of the chief offenders of metaphysical obscurity was John Donne (1572–1631) a widely travelled courtier and diplomat for Queen Elizabeth who composed knotty, sometimes amorous verse. At 49, he became a Dean of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, composing devotions on mortality and religious verses called Holy Sonnets.

In his day, Donne was widely read. A century later, however, his poetry fell into obscurity. Then, in the 20th Century, he became a favorite with literary folk who embrace thorny, elusive texts that provide a payoff when one solves the puzzle. Just the sort of “major poet” who drives students batty.

Tackling Donne

|

| Isaac Oliver. (before 1622). Portrait of John Donne. Oil on canvas. |

So, have I scared you off? Let’s not panic. Let’s tackle one of Donne’s thorniest Holy Sonnets. As we did with Shakespeare’s, let’s follow our 3 steps of reading verse.

Step 1: Read Aloud

Holy Sonnet #14 is, of course, a Sonnet. And we have been learning how to read those. Let’s start by reading aloud and hearing the Rhyme Scheme. Use that pattern to identify stanzas. Here we go.

John Donne, Holly Sonnet, #14.

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;[2]

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurp’d[3] town to another due,

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy[4] in me, me should defend,

But is captiv’d, and proves weak or untrue.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov’d fain,[5]

But am betroth’d unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall[6] me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.[7]

[2] But knock: Compare Revelation 3.20, Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that person, and they with me

[3] Usurp’d: i.e. usurped, another way of saying a city under siege by an enemy.

[4] Viceroy: a governor ruling on behalf of a king

[5] Fain: i.e. gladly willing

[6] Enthrall: i.e. enslaved

[7] Except you ravish me: that is, unless you rape me

By now, you’re an old hand, right? The Rhyme Scheme is clear: a-b-b-a; a-b-b-a; c-d-c-d; f-f. The 14 lines are divided into four stanzas: 3 Quatrains and a Couplet. We’ll keep that structure in mind as we continue.

But is it an Italian or an English Sonnet? That final couplet is the clue: Shakespeare’s variant on the sonnet compresses a powerful punch line into two final lines that offset the Themes developed in the previous twelve. You can always trust the Rhyme Scheme in a sonnet to signpost the Turn, a dynamic shift in themes.

Step 2: the Plain Sense of the Words

Before we worry too much about themes, however, let’s be clear on the straightforward sense of the words. Who is talking to whom? About what?

The numerous footnotes point up the challenge in grasping vocabulary from a 500 year old poem. Still, the main idea seems clear enough: “Batter my heart, three-person’d God”: obviously, this sonnet is a prayer directed at God, the Holy Trinity of Christian faith. The poet is asking God to …

What? Batter his heart? Break and burn him? Besiege a town? What on earth is going on here? Even with the glosses provided, we struggle. “Heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together,” complains Dr. Johnson. What do we do with Donne’s starburst of notions and figures?

Schemes and Tropes

Donne’s sense eludes us because it is expressed in a startling array of figurative language.

Figures of Speech: a form of expression in which language departs from conventional norms in its patterns (Scheme) or meaning (Trope) for maximum rhetorical effect

Scheme: repeated patterns of expression that enhance the rhetorical effect of the text: e.g. alliteration, anaphora, catalogue, parallelism

Trope: a figure of speech that plays on meaning so that the implied message differs from the ordinary sense of the expression.

Ever since the 2nd Chapter of our text, we have been recognizing figures of Scheme: rhythmical patterns that enhance the impact of a speech, text, or narrative. Remember Dr. King using Anaphora to grab the hearts of his audience in the “I have a Dream” speech?

We have not yet said much about Tropes, which ask readers to process a Signification other than what the language directly “says.” We have discussed Irony, a discrepancy between what is said and what readers intuit through comparison. More specifically, a Trope “uses words in senses beyond their literal meanings. … Tropes change the meanings of words, by a ‘turn’” of sense” (Trope, 2015). A Trope seems to assert something which we understand cannot be “real” to characterize something that is real or convey a larger truth.

I knew it! This is where the English teacher forces us to figure out some impossible secret language.

Well, it is true that poets use a lot of tropes, often in cryptic expressions that take time to unpack. But you use and understand tropes in every day of your life. Suppose someone says this to you:

Angie really broke my heart.

Do you have any trouble understanding the remark? Of course not. You know that nothing has happened to the heart pumping in your friend’s chest. Heart here is a way of talking about some deep level of passion and commitment. This is a Trope and you have no difficulty with it.

People use tropes all the time. Clever people use them to manipulate audiences in business meetings or social gatherings. Pastors use them in their sermons. Politicians use them to appeal to voters’ passions. Comedians use them to compose jokes. An educated person knows how to recognize and process common tropes. Let’s look at four that will help us with Donne.

Simile: a trope that explicitly compares a “literal” with a “figurative” term, usually indicating the comparison with like or as

Metaphor: a trope which denotes a “non-literal” thing, idea, or action to characterize a “real” term

Paradox: a trope in which two terms in a statement seem contradictory but suggest an elusive point

Personification: a trope which speaks of an abstract concept as if it is a person

Decoding Holy Sonnet #14

Step 3: Track patterns of sense and meaning that suggest deeper signification: i.e. themes

Let’s just identify some key Tropes in the sonnet.

- Stanza 1: a series of verbs denoting metaphorical attacks on the poet’s person that are supposed to, paradoxically, mend and renew

- Stanza 2: a simile in which the poet compares himself to a walled city in which the poet strives to open the gates to a besieging force but fails because the personification of Reason, God’s viceroy, or metaphorical best influence on the heart, is weak and conquered by sin

- Stanza 3: a metaphor of marriage to sin from which the poet realizes he must obtain a divorce in order to freely and obediently love God

- Thematic Turn: a vision of restored communion with God

- Final couplet: paradoxical invitation to God to liberate the poet by enslaving him, to restore him to chastity by compelling love from one whose sin renders him incapable of receiving love

Clearly, these Tropes take some decoding. But the real challenge is spiritual. Compare the teaching of the Apostle Paul:

We can read Donne’s poem as an unnecessarily difficult reflection expressed in convoluted figures. If we enjoy puzzles, we can welcome the cryptic challenges.

Or we can read the poem as a spiritual reflection on the great Paradox of the Christian faith. Salvation requires a sinner to repent and embrace a life of devotion and obedience to God. But the habits and addictions of sin make repentance and faith impossible. To find faith and be set free from sin, a “higher power” must break through one’s enslaved will and open up a new will capable of embracing Christ’s salvation.

By challenging us with Tropes that are very difficult to process, Donne forces us to confront the spiritual challenges of salvation. Sometimes, the difficulty of art is the point.

References

Donne, J. Poem #74. In Holy Sonnets. (1633). https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44106/holy-sonnets-batter-my-heart-three-persond-god.

Hester, M. T. (2006). Donne, John. In D. S. Kaslan, D. S. (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195169218.001.0001/acref-9780195169218-e-0141?rskey=lSIn2y&result=7.

Johnson, S. (1779). Excerpt from “Preface to Abraham Cowley.” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69382/from-lives-of-the-poets.

Oliver, I. (before 1622). Portrait of John Donne. London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1849. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Donne_by_Isaac_Oliver.jpg.

Trope [Article]. (2015). In C. Baldick (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780198715443.001.0001/acref-9780198715443-e-1172

a consistent pattern of choices regarding form and technique that comprise an identity for an artistic tradition, movement, or individual vision

repeated patterns of expression that enhance the rhetorical effect of the text: e.g. alliteration, anaphora, catalogue, parallelism

a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses: e.g. “I have a dream …” phrase repeated in Dr. Mar-tin Luther King’s speech, (8/28/1963).

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

an often wryly humorous, indirect mode of communication that asks the reader to compare what is said with some known or signified reference. Frequently used to puncture false pretentions, especially of the social elite. E.g. a standup comedian who relies on the audience to draw on what it knows about a celebrity to get the joke.

a figure of speech that plays on meaning so that the implied message differs from the ordinary sense of the expression. E.g. hyperbole, irony, metaphor, paradox, personification, simile.

a trope in which two terms in a statement seem contradictory but suggest an elusive point: e.g.: “the child is father of the man (William Wordsworth, “My Heart Leaps Up, 1802).