Chapter 9 Rules and Reactions

Imagine you are an artist who wants to earn a reputation for elite achievement. Question:

Should you focus on following the rules of convention?

Or should you gleefully, creatively break the rules?

Well, that depends on context, of course. Suppose you are composing tomb wall paintings for a Pharaoh in ancient Egypt. In that context you’d better follow those strict, centuries-old stylistic rules that affirmed the stable authority and society of the Nile. Unless your Pharaoh was named Akhenaten.

The Amarna Reaction

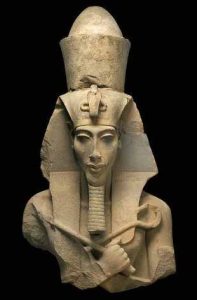

In the 14th Century BCE, a highly unconventional king named Akhenaten became Pharaoh. Akhenaten had startlingly new ideas and ideologies, including a reformed religious vision that exalted a Sun God as a nearly monotheistic divinity.

|

|

|

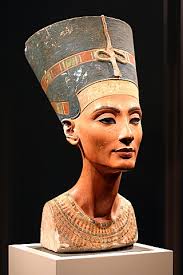

| Akhenaten & Nefertiti worshipping the Solar Disc and receiving life from its rays. 14th Century BCE. | Pharaoh Akhenaten. (14th C. BCE) Sandstone | Nefertiti. (14th C BCE). Painted limestone. |

Out of this ideological change grew a remarkable new “Amarna” style of art. Images of the king are more individuated, even unflattering, depicting a homely man with a thin neck and large nose. The forms within the images are amazingly original: graceful arcs and curves delineating limbs that seem to be in motion. For many today, the bust of Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s wife, is an iconic example of Egyptian art. Yet it is actually very different from the traditional style, an exercise in Amarna elegance that plays well with modern tastes.

So you want to succeed as an ancient Egyptian artist? Work for most Pharaohs and you’d better follow the rules. Work for Akhenaten and you can pioneer a glorious new style.

Rules and Reactions

We’ve been exploring various Classicisms, all of which established firm Conventional rules and requirements that gave form to the social status quo. But here’s the thing.

All classicisms breed rebellions. Whether or not the rebellion is successful, the old styles have a way of remaining resilient. Akhenaten’s ideological, religious, and aesthetic rebellion evaporated at his death as Egypt swung back to old ways. Some eras remain culturally stable for long periods of time. Others erupt into volatile cycles of rules and reactions.

During the late 18th and 19th Centuries, European-American cultures and their arts have been convulsed by succeeding waves of restrictive Conventions and restless rebellions. And, really, the reactionary cycles have never stopped. Let’s take a look.

References

Akhenaten and Nefertiti worshipping the Solar Disc and receiving life from its rays [Relief sculpture]. (c 1360). Cairo, EG: The Egyptian Museum in Cairo. AN 2Ak.605b https://egypt-museum.com/house-altar-of-akhenaten-and-his-family/

Bust of Queen Nefertiti [Frieze]. (ca. 1348-1335 BCE). Berlin, Germany: Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz. https://recherche.smb.museum/detail/606189/b%C3%BCste-der-k%C3%B6nigin-nofretete?language=de&question=Nefertiti&limit=15&sort=relevance&controls=none&objIdx=0

Pharaoh Akhenaten [Statue]. (14th Century BCE) Cairo, EG: The Egyptian Museum. https://egypt-museum.com/colossal-statue-of-akhenaten/

often contrasted with “romantic” folk traditions, an aesthetic associated with a social elite and a venerated past, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Characterized by clarity, order, balance, symmetry, reason, mathematical precision

an aspect of art which is expected and understood by the audience in a particular tradition