7.6 Northern Oil and Light

As an Italian, Vasari focused his history of the Renaissance on the Artists of Milan, Venice, Rome, and his native Florence. He occasionally noted that some innovative work was being done far to the north.

Flanders, the Netherlands, and Germany were also being transformed by wealth and Humanism. However, the rediscovery of Classical learning that was instructing Italian Artists was slow to work its way North. In the 15th Century, the rituals, images, and mysticism of Medieval Catholicism remained strong. However, a folksy form of Humanism was opening new opportunities for Northern artists.

Brueghel: Artist of the People

In 1520, Martin Luther led a religious rebellion against the authority of the Roman popes. Northern Flanders became Reformed Holland and German states to the North adopted Lutheran independence.

What mattered to artists was the Protestant rejection of religious imagery. Reformed churches especially condemned traditional Icons as sinful idolatry. So what was an artist to do?

Pieter Brueghel the Elder of Antwerp turned his attention to the common life of the people in busy scenes of village life. The Wedding Feast assembles dozens Men and women caught in a moment of vibrant celebration. The Beggars, also known as The Cripples, sympathetically documents the resilient if uncouth perseverance of the unempowered. Notice that these images lack the precise Mimetic detail that Italian Renaissance artists were learning from Classical models. Rounded, Stylized forms suggest rather than perfectly imitate figures and subjects.

|

|

|

| The Wedding Dance (1566). Oil on panel. | The Beggars. (1568). [Painting]. Oil on panel

|

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. (c 1557). Oil on Panel transferred to canvas |

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus looks back and ahead. The Dutch tradition of painting would embrace land and seascapes not as secondary backdrops in the Italian manner, but as a major compositional challenge worthy of primary focus. Yet if you look very carefully, you’ll see the startling image of a youth hurtling down out of the sky. In Greek mythology, Icarus was the son of Daedalus, a great engineer who invented wings to escape imprisonment. Icarus grabbed the wings, flew too close to the sun, and fell to his death when the wax melted and the feathers fell away.

Brueghel is said to have associated with Humanist scholars, and the reference to Icarus nods at the Classical tradition. Yet it is here reduced to a distant anomaly which no one in the scene seems to notice.

Cranach’s Portraits

Lucas Cranach worked in Saxony, the region in which Martin Luther’s Reformation took hold. He knew Luther well and painted portraits of the great theologian in various stages of life.

|

|

|

| Portrait of Martin Luther. (1543). Oil on panel. | Dr. Johannes Cuspinian. (c.1502-3). Oil on panel. | Anna Cuspinian. (c.1502-3). Oil on panel. |

Cranach painted relatively simple versions of Christian and mythological subjects—the Lutheran churches of Germany were less adamantly opposed to icons than were the Reformed congregations of the Netherlands. However, Cranach was primarily known as a portrait painter. The twin portraits of the Cuspinians are typical examples of the compositions that wealthy burghers in the North commissioned as patronage of lavish church iconography dropped out of favor.

Van Eyck: Pioneer of oil paint

Now let’s go back a bit to the middle of the 14th Century. What media were those Italian masters using for their painting? You remember that they worked in Tempera, pigment suspended in egg yolk, either on boards or in wet plaster (Fresco). But is that what you think of as the preferred paint Medium? If you think of it at all, you probably think of oil-based paint.1

Now Oils were pioneered in the north, not the south. The Flemish master Jan van Eyck did not invent Oils, but he was one of its first great practitioners.

Van Eyck revolutionized [oil painting] technique and brought it to a sudden peak of perfection. He showed the medium’s flexibility, its rich and dense color, its wide range from light to dark, and its ability to achieve both minute detail and subtle blending of tones (Oil Paint 2005).

Jan van Eyck’s unprecedented technical mastery of light and space, together with his innovative use of oils, gained him the admiration of painters … and collectors. … Vasari attributed the invention of oil painting to Jan van Eyck; this claim is inaccurate, but it is an extraordinary testimony to Jan van Eyck’s reputation in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe (Eyck, Jan van, 2005).

The development of oils vastly increased painters’ capabilities. Oil suspends and fixes color pigments but dries slowly and permits almost infinite working and reworking by the artist. Oil paint can be mixed in varying levels of color saturation, including nearly transparent Glazes. It can be applied in layers, creating textures that painters use with great variety and effectiveness. Impasto, for example, applies oil paint, often with a palette knife, to produce thickly textured masses of color.

We can see the impact of this innovative medium in van Eyck’s portraits. Man with a Red Turban (possibly a self-portrait) illustrates the subtlety, richness, and vividness that can be achieved in oil. For the full impact of the technique and textures of brushwork, paint, and surface, of course, one must stand before the original painting. But zoom in to gain a much richer experience. In the portrait of Gonella, we see—gasp!—humor. Renaissance art is escaping the Church monopoly with its dour obsession with the death of Christ. Notice, too, the rich, organic modeling and colors made possible with linear perspective and oil paint.

|

|

|

| Portrait of a Man with a Red Turban. (1433). Oil on Oak. | Gonella, Court Dwarf of Dukes of Ferrara. (1433). Oil on oak. |

Arnolfini Portrait. (1434). Oil on Panel. |

The famous Arnolfini Portrait has often been erroneously entitled Wedding Portrait. Whatever the title, it does portray an affluent couple surrounded by symbols of conjugal blessing. The burning candle in the chandelier suggests the presence of God. Shoes are removed to indicate the holy ground of the union. The dog represents faithfulness. And of course, the bed and the suggestion of the woman’s pregnancy prophesy the blessing of parenthood.

But notice something else. Where is the light? That is, where does light appear to be coming from in the scene portrayed by the composition? van Eyck takes light seriously. He makes the light source clear: the window on the left. And he carefully traces its lines in zones of light and shadow. He even places a convex mirror on the rear wall offering a reverse angle look at the Arnolfinis’ backs.

Virtual light sources within the projected scene and their resulting patterns of light and shadow became a major concern for the two primary genres of Dutch painting: Land or Seascapes and interior domestic scenes which came to be called Genre Paintings. Many traditions of painting had paid little attention to internal light—only the light shining on the painting mattered. But the pioneering work of van Eyck and others faced painters with a question that would for centuries need to be answered: where is the light coming from and what aspects of the subjects should be lit?

Dürer the Intermediary

In the mid-15th Century, Northern painters knew little of the precisely calculated linear perspective being perfected by Italian artists. At the same time, Italians like Masaccio were working in Tempera, not Oils. Of course, travel and communication were far more challenging then. It took time for both regions to learn from the other.

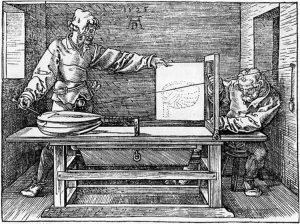

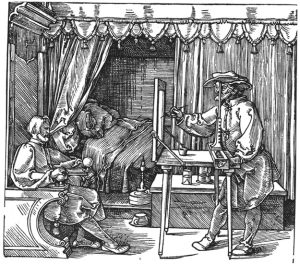

In the 1490s, a young German artist named Albrecht Dürer went on a grand tour of Europe. In Italy, he shared the techniques of Oils and learned the lessons of Linear Perspective. On his return, he demonstrated the power of perspective and produced instructional woodcuts on how to create and use drawing devices for accurate precision. Notice the careful linear perspective in the buildings of his Paumgartner Altarpiece.

|

|

|

| Paumgartner Altar. (1500). Oil on panel. | Man Drawing a Lute. (1523). Woodcut. | Albrecht Dürer. A Draughtsman Drawing a Portrait. (1523). Woodcut. |

Dürer had a healthy ego. His extravagant self-portraits demonstrate the profoundly changing status of artists during the Renaissance. Medieval artists had toiled in nearly complete anonymity. E.g. the master stone masons who carved the magnificent reliefs in Gothic cathedrals are almost completely unknown to us. But the most successful artists of the Renaissance gained rock star social status and earned enormous sums of money. We’re about to meet two of the greatest celebrities of the Renaissance world.

|

|

| Self-portrait with Gloves. (1498). Oil on panel. | Self-portrait in a fur-trimmed coat. (1500) Oil on panel. |

Vital Questions

Context

Approaching the Renaissance era, we need to distinguish between the North and the South. The Dutch and German Renaissance shared both the Christian and the Humanist backgrounds of the Italian Renaissance. However, the artists and their patrons were probably less oriented to the scholarly erudition that was rampant in the South.

We must also be aware of the declining emphasis on Christian iconography in Protestant Germany and the Netherlands. Radical Protestants went so far as to tear down statues and paint over Frescoes which they considered to be idolatrous.

Content

This shift away from iconography did not mean that overtly Christian art disappeared. It did, however, lead Northern artists in a new direction. Portraits became a painter’s most reliable source of income. And Landscapes, seascapes, and domestically oriented Genre Paintings developed as major traditions. We will see how fruitful those traditions became.

Form

The development of oil paints profoundly altered the possibilities for painting technique, as we will see. We should also mention the impact of internal light sources on the composition of a painting. The dramatic possibilities would be evident in the High Renaissance and the Baroque period which followed.

References

Breughl, Pieter the Elder. (1568). The Beggars [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. AN RF 730. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010061789

Breughel, P. Elder. (1560). Landscape with the Fall of Icarus [Painting]. Brussels, Belgium: Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/pieter-bruegel-the-elder/landscape-with-the-fall-of-icarus-1560

Breughel, Pieter the Elder. (1566). The Wedding Dance [Painting]. Detroit MI: Detroit Institute of Arts. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/pieter-bruegel-the-elder/the-wedding-dance-in-the-open-air

Cranach, Lucas the Elder. (c.1502-3). Anna Cuspinian. [Painting]. Winterthur, Switzerland: Oskar Reinhart Foundation. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/lucas-cranach-the-elder/anna-cuspinian

Cranach, Lucas the Elder. (c.1502-3). Dr. Johannes Cuspinian. [Painting]. Winterthur, Switzerland: Oskar Reinhart Foundation. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/lucas-cranach-the-elder/dr-johannes-cuspinian

Cranach, L. Elder. (1543). Portrait of Martin Luther [Painting]. Nuremberg, Germany: Germanisches Nationalmuseum. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/lucas-cranach-the-elder/portrait-of-martin-luther-1543

Dürer, A. [Article]. (2003). G. Campbell (Ed.), in The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-1196

Dürer, A. (1500). Paumgartner Altar [Painting]. Munich, Germany: Alte Pinakotech. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/albrecht-durer/paumgartner-altar

Dürer, A. (1523). Man Drawing a Lute [Woodcut]. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/albrecht-durer/man-drawing-a-lute-1523

Dürer, A. (1523). A Draughtsman Drawing a Portrait [Woodcut]. London, UK: Victoria and Albert Museum https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1028541/a-draughtsman-drawing-a-portrait-woodcut-durer-albrecht/a-draughtsman-drawing-a-portrait-woodcut-d%C3%BCrer-albrecht/

Durer, A. (1500). Self-portrait in a fur-trimmed coat. [Painting]. Munich, Germany: Alte Pinakotech. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.11664569

Dürer, A. (1500). Self-portrait in a fur-trimmed coat [Painting]. Munich, Germany: Alte Pinakotech. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/albrecht-durer

Dürer, Albrecht. (1498). Self-portrait with Gloves [Painting]. Madrid, SP: Museo del Prado. https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/obra-de-arte/autorretrato/8417d190-eb9d-4c52-9c89-dcdcd0109b5b?searchMeta=durer

Eyck, Jan van [Article]. (2005). Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Campbell, G. (Ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-1318?rskey=zIJDEZ&result=3

Oil Paint [article]. (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Art. Campbell, G. (Ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-2559?rskey=sMRLBs&result=2

Van Eyck, J. (1434). Arnolfini Portrait. (Wedding Portrait) [Painting]. London: National Gallery. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jan-van-eyck-the-arnolfini-portrait

van Eyck, J. (1433). Gonella, the court dwarf of the Dukes of Ferrara [Painting]. Vienna, Austria: Kunsthistorisches Museum. https://www.khm.at/en/artworks/the-court-jester-gonella-735-1

Van Eyck, J. (1433). Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban [Painting]. London: National Gallery, NG222. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jan-van-eyck-the-arnolfini-portrait

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

A) a 14th Century shift in European culture from a narrow, exclusive focus on scripture and Church interests to a broader interest in cultural traditions, especially those of classical Egypt, Greece and Persia. B) a perspective that values and focuses on the capacities of human beings for knowledge, wisdom, and creativity.

1) an image which signifies a holy figure for worship or devotion. 2) a Christian image of Jesus or saints which focuses worship and prayer. 3) a Byzantine genre of holy mosaics and paintings that depicts holy figures according to a conventional style. 4) In contemporary scholarship, an image that signifies a conventional meaning recognized by an audience despite the absence of any visual resemblance.

art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

a representational technique that depicts the idea of a visual subject through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis

a paint medium that fixes pigment in egg yolk to produce vivid effects. Popular in Europe before the development of oil paint, tempera dries quickly, compelling the painter to work rapidly and limiting the possible effects.

a painting medium in which pigments are applied to wet, freshly applied plaster, which acts as a binding medium as it dries

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative

in oil paintings, a glassy surface effect achieved by layering thinly pigment-ed coats over deeper hues

the application of oil paint, often with a palette knife, to produce thickly textured masses of color

paintings that depict domestic scenes and elements of daily life, associated with 17th-century Dutch artists who were commissioned by house-proud patrons. Disdained by 18th and 19th Century academic artists as a lesser form.

a paint medium that suspends and fixes pigment in a base of linseed or other oil. Oil paint dries slowly and can be worked, reworked, and applied in layers and glazes of varying levels of saturation, permitting the buildup of subtle, complex visual effects.

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

A conventional system of significations that associate details of appearance with particular religious figures

in visual art, a composition that represents a human subject as an individual, meticulously capturing physical or psychological likenesses

crucial to the development of art during the European Renaissance, a paint medium that suspends and fixes pigment in a base of linseed or other oil. Oil paint dries slowly and can be worked, reworked, and applied in layers, thus permitting the buildup of subtle, complex visual effects

the 17th Century artistic tradition that followed the Renaissance, characterized by gritty social realism, dramatic action, depth of characterization, closed compositions, and intense contrasts between light and shadow. More broadly, any art emulating the values of the Baroque