6.2 Homer’s Epic World

Epic poetry … is an imitation in verse of characters of a higher type … and is narrative in form. … The Epic action has no limits of time.

I call a plot ‘episodic’ in which the episodes or acts succeed one another without probable or necessary sequence.

– Aristotle, Poetics, from Parts V and VII

Aristotle’s main point about epic narrative is that it is unlimited in length, and, frankly, this sprawling formlessness bothers him. Today, we use the word episodic for narratives which roll along from one incident to the next without clear structural unity: for example, episodic video dramas which can go on for years adding episode “stories.”

In his definition of epic, Aristotle refers to social class. His Classical orientation makes much of a distinction between art forms that reflect and appeal to higher and lower orders of society. The Poetics’ model for the epic is Homer’s pair of narratives of a legendary 10-year war. Prince Paris of Troy, a powerful city on the eastern side of the Aegean sea, rapes and kidnaps Helen, Queen of Sparta. Kings of Greek-speaking cities form a revenge-driven alliance.

It is difficult today to imagine how profoundly Homer’s narratives permeated Greek culture. The texts are attributed to a legendary blind poet who compiled oral myths of kings, heroics, and the Gods’ interventions in human affairs. Homer combined theology, history, and socializing values in an all-encompassing myth.

Now, as Aristotle says, Epics are long. Very, very long. We will only dip our toe into the ocean and sample a few scenes. Let’s peek into the Odyssey.

The Odyssey, from Book I

Tell me, O muse, of that ingenious hero who travelled far and wide after he had sacked the famous town of Troy. Many cities did he visit, and many were the nations with whose manners and customs he was acquainted; moreover he suffered much by sea while trying to save his own life and bring his men safely home; but do what he might he could not save his men, for they perished through their own sheer folly in eating the cattle of the Sun-god Hyperion;[1] so the god prevented them from ever reaching home. Tell me, too, about all these things, O daughter of Jove,[2] from whatsoever source you may know them.

So now all who escaped death in battle or by shipwreck had got safely home except Ulysses,[3] and he, though he was longing to return to his wife and country, was detained by the goddess Calypso, who had got him into a large cave and wanted to marry him. But as years went by, there came a time when the gods settled that he should go back to Ithaca; even then, however, when he was among his own people, his troubles were not yet over; nevertheless, all the gods had now begun to pity him except Neptune, who still persecuted him without ceasing and would not let him get home.

Traditional epics begin with invocations that seek blessing from a Muse, one of nine minor deities who inspired artists. Homer asks Calliope, the patron muse of poets, to “tell” him the tale he relates in his voice. He then summarizes in a few sentences the ten-year war story of The Iliad, shifting primary focus to the wily King Ulysses (Greek name: Odysseus) of Ithaca who devises a plot to win the war: soldiers hide in a big wooden horse which the Trojans wheel into their walled city after Greek armies have apparently departed.

Aha! Now I see why people say “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts”!

|

|

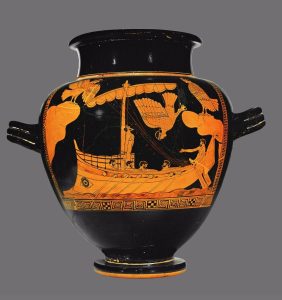

| Siren Painter. (c 500 BCE). Odysseus with the Sirens. Terra cotta red figure | Penelope Painter. (c 420 BCE). Odysseus Slaying the Suitors Terra cotta red figure |

After Troy’s fall, Ulysses and his army set off in ships to cross the Aegean and return home. Now, the Aegean Sea is about 180 miles wide. Yet Ulysses’ journey lasts a decade. In both the Iliad and Odyssey, the gods in Olympus divide their patronage between the Greeks, the Trojans, and individual heroes. Neptune (Greek name: Poseidon) god of the sea, supports the Trojans and hates Ulysses: he hurls at our intrepid hero a decade of obstacles and dangers. The wily adventurer survives through the patronage of Minerva (Greek name: Athena) goddess of wisdom. It’s a great tale, complete with a journey to the under-world of the dead. In the final book, Ulysses returns home to Penelope, a wife who, beset by suitors lusting after the empty throne, has been struggling to remain faithful for twenty long years.

from Book XXIII

Euryclea[1] now went upstairs laughing to tell her mistress that her dear husband had come home. Her aged knees became young again and her feet were nimble for joy as she went up to her mistress and bent over her head to speak to her. “Wake up Penelope, my dear child,” she exclaimed, “and see with your own eyes something that you have been wanting this long time past. Ulysses has at last indeed come home again, and has killed the suitors who were giving so much trouble in his house, eating up his estate and ill-treating his son.”

“My good nurse,” answered Penelope, “you must be mad. … Why should you thus mock me when I have trouble enough already- talking such nonsense, and waking me up out of a sweet sleep that had taken possession of my eyes and closed them?” …

“My dear child, I am not mocking you. It is quite true as I tell you that Ulysses is come home again. He was the stranger whom they all kept on treating so badly in the cloister.”

Then Penelope sprang up from her couch, threw her arms round Euryclea, and wept for joy. “But my dear nurse, … if he has really come home as you say, how did he manage to overcome the wicked suitors single handed, seeing what a number of them there always were?”

“I was not there and do not know; I only heard them groaning while they were being killed. … I found Ulysses standing over the corpses that were lying on the ground all round him, one on top of the other. You would have enjoyed it if you could have seen him standing there all bespattered with blood and filth and looking just like a lion. …

“He has sent me to call you, so come with me that you may both be happy together after all; for now at last the desire of your heart has been fulfilled; your husband is come home to find both wife and son alive and well, and to take his revenge in his own house on the suitors who behaved so badly.” …

Penelope came down from her upper room, and … considered whether she should keep at a distance from her husband and question him, or whether she should at once go up to him and embrace him. When, however, she had crossed the stone floor of the cloister, she sat down opposite Ulysses by the fire, against the wall … while Ulysses sat near one of the bearing-posts, looking upon the ground, and waiting to see what his wife would say to him when she saw him. For a long time, she sat silent and as one lost in amazement. At one moment she looked him full in the face, but was misled by his shabby clothes and failed to recognize him.

Then Telemachus began to reproach her and said: “Mother, … why do you keep away from my father in this way? Why do you not sit by his side and begin talking to him and asking him questions? No other woman could bear to keep away from her husband when he had come back to her after twenty years of absence, and after having gone through so much; but your heart always was as hard as a stone.”

Penelope answered, “My son, I am so lost in astonishment that I can find no words in which either to ask questions or to answer them. … Still, if he really is Ulysses come back to his own home again, we shall get to understand one another better by and by, for there are tokens with which we two are alone acquainted, and which are hidden from all others.”

Ulysses smiled at this, and said to Telemachus, “Let your mother put me to any proof she likes; she will make up her mind about it presently. She rejects me for the moment and believes me to be somebody else, because I am covered with dirt and have such bad clothes on.” …

Thus did he speak, and they did even as he had said. … The upper servant Eurynome washed and anointed Ulysses in his own house and gave him a shirt and cloak, while Minerva[2] made him look taller and stronger than before; she also made the hair grow thick on the top of his head, and flow down in curls like hyacinth blossoms; she glorified him about the head and shoulders just as a skillful workman who has studied art of all kinds. … He came from the bath looking like one of the immortals, and sat down opposite his wife on the seat he had left. “My dear, heaven has endowed you with a heart more unyielding than woman ever yet had. No other woman could bear to keep away from her husband when he had come back to her after twenty years of absence, and after having gone through so much.”

“My dear,” answered Penelope, “I have no wish to set myself up, nor to depreciate you; but I am not struck by your appearance, for I very well remember what kind of a man you were when you set sail from Ithaca. Nevertheless, Euryclea, take his bed outside the bed chamber that he himself built. Bring the bed outside this room, and put bedding upon it with fleeces, good coverlets, and blankets.”

She said this to try him, but Ulysses was very angry and said, “Who has been taking my bed from the place in which I left it? He must have found it a hard task, no matter how skilled a workman he was, unless some god came and helped him to shift it. There is no man living, however strong and in his prime, who could move it from its place, for it is a marvelous curiosity which I made with my very own hands.

There was a young olive growing within the precincts of the house, in full vigor, and about as thick as a bearing-post. I built my room round this with strong walls of stone and a roof to cover them, and I made the doors strong and well-fitting. … I then bored a hole down the middle and made it the center-post of my bed, at which I worked till I had finished it, inlaying it with gold and silver; after this I stretched a hide of crimson leather from one side of it to the other. So you see I know all about it, and I desire to learn whether it is still there, or whether any one has been removing it by cutting down the olive tree at its roots.”

When she heard the proofs Ulysses now gave her, she fairly broke down. She flew weeping to his side, flung her arms about his neck, and kissed him. “Do not be angry with me Ulysses,” she cried, “you, who are the wisest of mankind. We have suffered, both of us. Heaven has denied us the happiness of spending our youth, and of growing old, together; do not then be aggrieved or take it amiss that I did not embrace you thus as soon as I saw you. I have been shuddering all the time through fear that someone might come here and deceive me with a lying story; for there are many very wicked people going about. … Now, however, that you have convinced me by showing that you know all about our bed … hard of belief though I have been I can mistrust no longer.”

Then Ulysses in his turn melted and wept as he clasped his dear and faithful wife to his bosom. As the sight of land is welcome to men who are swimming towards the shore, when Neptune[3] has wrecked their ship with the fury of his winds and waves … even so was her husband welcome to her as she looked upon him, and she could not tear her two fair arms from about his neck. Indeed, they would have gone on indulging their sorrow till rosy-fingered morn appeared, had not Minerva determined otherwise, and held night back in the far west, while she would not suffer Dawn[4] to leave Oceanus,[5] nor to yoke the two steeds … that bear her onward to break the day upon mankind.

|

| Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. (19th C.). Odysseus and Penelope |

And so, this Hero’s Journey comes to an end (almost). Thus Bilbo Baggins and his nephew Frodo after him return to the Shire after their adventures. Thus Harry Potter rests in the sun at the end of his travails. Thus Luke Skywalker returns to a hero’s welcome in Star Wars, Episode IV: A New Hope. (Episodic narrative!) Thus Hugh Glass finds peace in the mountains at the end of The Revenant (2015). Thus, Katniss Everdeen survives mental turmoil and lives to bear children in a world without hunger games. Epics have been with us a long time, and will probably always be.

References

Aristotle. (c 350 BCE). Poetics. Butcher, S. H. Translator. (1922). London: Macmillan. Internet Archive https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.html

Homer. (c 8th C BCE). The Odyssey. Butler, S. Translator. (1897). London, UK: Longmans, Green, & Co. Internet Archive https://classics.mit.edu/Homer/odyssey.1.i.html

Penelope Painter. (c 420 BCE). Skyphos, side A: Odysseus Slaying the Suitors [Red figure vase]. Berlin: GE. SAaatliche Museen zu Berlin, Altes Museum. https://recherche.smb.museum/detail/686889/attischer-skyphos?language=de&question=Penelope&limit=15&sort=relevance&controls=none&collectionKey=ANT*&objIdx=1

Siren Painter. (c 500 BCE). Odysseus with the Sirens [Red-figure pottery]. London, UK: British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1843-1103-31

Tischbein, J. H. W. (19th C.). Odysseus and Penelope [Painting]. Dortmund, Germany. Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odysseus_und_Penelope_-_Johann_Heinrich_Wilhelm_Tischbein.jpg

an extended, mythic narrative celebrating the trials and triumphs of heroes exemplifying a culture’s treasured values and orienting its origins

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

an immensely widespread narrative template in which a protagonist is called from ordinary life to an adventure in a challenging or dangerous realm and returns bearing a treasure of some kind