5.3 The “Classics”

We began this chapter with an exploration of some terms people often use but rarely define precisely: Classic and Classical. Well, here’s another one for our list: Classics.

In the European educational tradition, Classics referred to works of ancient Greece and Rome: their languages, histories, literatures, and arts. During the Middle Ages, European culture developed out of the vestiges of ancient Rome preserved by the Church of Rome. Roman culture itself was shaped by the influence of Greek mercantile colonies. Most European and Euro-American cultural roads lead back to Greece.[1]

Don’t believe me? OK, let’s pose a question. What is the most important indicator of an artist’s skill? What must an artist be able to do to impress you? Did you answer something like this?

An artist must be able to accurately imitate the realistic appearance of visual subjects to create the illusion of seeing “the real thing.”

If that’s what you answered, you are channeling Classical Greek ideas of art, ideas that have only rarely dominated people’s artistic standards over the centuries.

[1] Of course, the cultural situations are much more complicated than this sketch suggests. Whether we speak of Germanic tribes fusing with vestiges of Empire in Western Europe or Spanish, French, or English colonists being re-invented through contact with the indigenous peoples of the Americas, intercultural influences move in both directions.

Archaic Greek Art

Surrounded by the Mediterranean, Greeks took to the sea, cultivating trading relationships with nearby peoples. From the Phoenicians, Greeks learned maritime trade techniques and how to write with a phonetic alphabet. Greek culture was especially influenced by the sophisticated culture of the Nile, Egyptian myths, thought, technology, and art.

| Kouros figure. (6th C. BCE). Attributed to Myron. Marble sculpture. | Kore figure, Lady of Auxerre. (c. 630 BCE). Incised limestone. |

We can see the impact of Egypt in the artistic styles of what scholars call Greek’s Archaic era. Votive[2] figures from this time are clearly influenced by Egyptian models. Notice how the Kouros and Kore figures emulate Egyptian statuary: the timeless stance, the abstract, stylized features, and the vacant smiles.[3] In the hair and fixed smile of these figures, we also see the influence of Mesopotamian cultures. (No time here for a close look at Assyrian and Babylonian art!)

[2] Votive: a gift offered to honor a god and used within a worship ritual.

[3] In the hair and fixed smile of these figures, we also see the influence of Mesopotamian cultures. No time here for that tale!

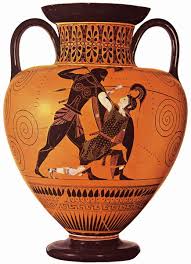

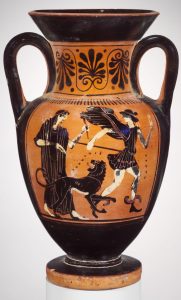

Then Greek artists began to innovate. Red and Black figure vases and amphorae of the 6th and 5th Centuries depicted scenes from daily life and heroic athletes and warriors. Remarkably, the figures are depicted in motion. Greek art was coming alive.

|

|

| Exekias. (6th Century BCE). Achilles Killing Penthelisea. Black figure terracotta amphora (jar) | Diosphos Painter (c. 500 B.C.), Black-figure amphora (jar) |

It may not seem remarkable today, but the fact that those black and red figure potters depicted action marked a profound change in artistic possibilities. We’ve seen action in some other traditions, but not necessarily activity conceived of as a visual scene:

|

|

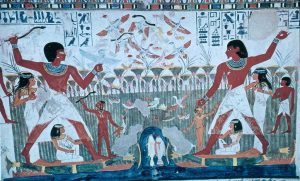

| Fowling Scene. (c 1400 BCE). Wall Painting | Akragas Painter. (c 440 BCE). Amazons, Mythical Warrior Women. Red Figure Pottery. |

The Egyptian fowling scene shows ideas of action, the master hunting, servants fishing and reaping, birds flying, and fish swimming. But the figures are scaled according to social status, not actual size. The action is not particularly convincing. And figures are arranged in the painting’s ground with little attention to one’s visual experience of space. By contrast, the red figure image scales its figures realistically and composes them in a visually authentic space.

Can you see how our ideas of art are beginning to emerge? Now, we must from the beginning resist the urge to see these developments as an evolution from primitive to mature. That Egyptian painter was not a poor artist. He or she simply had different ideas of what painting was supposed to do. The point to see is about the emergence of a conception of art, one that still dominates many people’s ideas today, despite the fact that 20th Century artists brought it all back into serious question.

The Classical Period

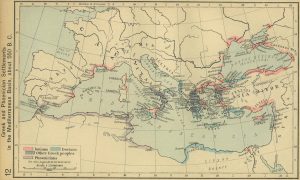

In the 5th and 4th Centuries, Greek dominance over the Mediterranean reached its peak. Trade colonies were established across the Mediterranean: Asia Minor, North Africa, Italy, southern France, and Spain. Beyond economic and political dominance, Greek culture achieved an almost unprecedented level of influence. Rome, for example, emulated Greek culture as it began to develop its power base. The entire Mediterranean world was dazzled by astonishing achievements in philosophy, medicine, geography, history, mathematics, democracy and the arts that shaped the Western world.

|

| Map of Greek and Phoenician trading settlements in the Mediterranean |

Now, “Greece” at the time was far from one fused entity. Dozens of distinct, rival city states quarreled and warred with each other. But they shared a language, athletic competitions, and a mythic tradition. They use the word barbarians for those who spoke no Greek and growled, to Greek-speaking ears, bar, bar, bar, bar.

|

|

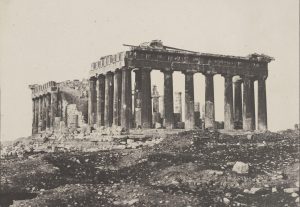

| Jakub Halum. (June 1, 2024). Acropolis. (495-429 BCE). | Eugène Piot, (1852). Parthenon. Salted paper print. |

Among these city states the polis of Athens reached a so-called “Golden Age” under the leadership of Pericles. Athens boasted magnificent architecture, especially on the Acropolis. The Parthenon, temple to Athena, Goddess of wisdom and patroness of the city, was a triumph of order and harmony. It also achieved a technological breakthrough for the day: roof trusses spanned much wider spaces between pillars than did those of Egyptian temples.

What do you see in the Parthenon? The columns? The pediment, that gable spanning the tops of the columns? Where have you seen these before? In the White House. The Securities and Exchange building on Wall Street. Neo-classical homes in your neighborhood. Inspiring architects into our own day, the look of the Parthenon well earns the term classical.

The Illusion of Seeing

The gates of art being now thrown open by Apollodorus, Zeuxis of Heraclea entered upon the scene. … There is a story, too, that at a later period, Zeuxis having painted a child carrying grapes, the birds came to peck at them; upon which, with a similar degree of candor, he expressed himself vexed with his work, and exclaimed—“I have surely painted the grapes better than the child, for if I had fully succeeded in the last, the birds would have been in fear of it.”

–Pliny the Elder. (79 CE) The Natural History

OK, let’s get down to it. Art as a “realistic” emulation of actual visual experience. The most pervasive common assumption about the requirement for artistic excellence. This is where it comes from.

Unfortunately, Classical Greek paintings have been almost completely lost into the eroding grind of time. What we know about great classical painters is what we learn from historians and philosophers. Fortunately, their legacy is rich, abundant, and insightful.

The legendary story of Zeuxis aspiring to lure actual birds to peck at painted grapes articulates an artistic orientation distinctive in the ancient world. As we have seen, artists in other traditions depicted bits of reality in order to cultivate religious devotions or to teach ideological lessons. Their representation of visual subjects included imitation but was free to distort its figures for stylistic reasons. Painting the hunting master in profile but with torso and eye facing the viewer is not an attempt to achieve realism sufficient to fool a bird.

To realistically imitate a visual experience is not an act of religious devotion or an ideological statement. It is a reflective act of analysis appropriate for a culture rich in philosophical reflection. Greek thinkers spent a lot of time trying to understand reality in itself. Its artists devoted themselves to analyzing and recreating its appearance. They called this commitment mimesis:

Mimesis: a representational technique in visual art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

Illusionism: the conviction that a painting or sculpture’s most important task is to imitate the appearance of nature as naturalistically as possible

As we will see, the line of influence leading to our artistic tastes today is a complex one. Nevertheless, the fundamental assumption that an artist needs to create an illusion of reality remains nascently dominant in our world. Each time people dismiss non-mimetic art in a museum—My child could have done that!—they channel the burden assumed by Zeuxis: if I am any good, I will be able to fool birds with my realism.

Classical Sculpture: living Mimesis

While classical Greek paintings are mostly lost to us, the hardier media of statues and reliefs have preserved them more abundantly. Actually, much of our “Classical Greek” sculpture is preserved by faithful Roman copyists, but some examples survive.

Classical sculptors reflected the naturalistic tastes of a culture influenced by philosophers like Aristotle who were fascinated by close, empirical observation and analysis. Classical Greek sculptors portrayed the human body with far more attention to anatomical detail than did other traditions.

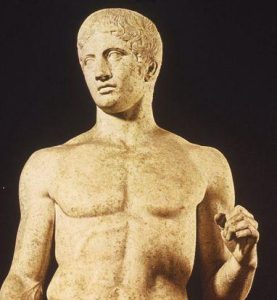

| King Menkaure & Queen. (2490-2472 BCE). | Kouros figure. (6th C. BCE). | Doryphoros [Spear Bearer]. (c 450-440 B.C.E.). Roman marble copy of bronze figure |

I commend you to closely compare these depictions of apparently similar visual subjects by following the links to the Jstor images. Zooming in, you can see the distinct differences in levels of anatomical detail. Consider the mimetic naturalism of the musculature depicted in the Spear Carrier (Doryphoros).

But the commitment to illusionism doesn’t stop with anatomical detail. Set aside the question of anatomical detail. Have you ever seen a person stand the way those Egyptian and Archaic subjects stand? Now look at the Spear Carrier. We do stand like that, don’t we. This sculpture imitates our visual experience of a body existing in time, poising its muscles and balance points against the pull of gravity. The mimesis of human movement has a name:

In classical sculpture, figures come vitally alive. Precisely modeled human forms suggest movement in time and express moods and attitudes. Some figures capture split-second moments in an action sequence. As Stansbury-O’Donnell puts it, figures display a more naturalistic sense of movement, … the patterns of movement and adjustment in the body in the performance of an action.” The Greeks called this rhythmos.

|

|

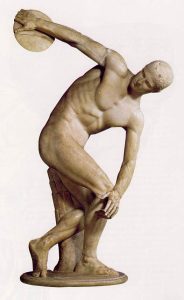

| Riace Warrior. (c.450 B.C). Bronze with silver and copper | Discobolus [Discus Thrower]. Bronze original c 450 BCE; marble copy c 2nd century CE |

In the Discobolus, we see a static, unmoving figures–it is carved from stone, after all!–mimetically captures the movement of an elite athlete. The effect is achieved by the capturing a split second in a flowing action which leads us to “see” Suggested Movement, the full arc of the athlete’s motion. We marvel at mimetic precision on multiple levels: the anatomy of the athlete, the kinetic flow of the muscles, the sequence of balance points and force shifts, and a technique which a track and field coach would be happy to use to instruct shot-putters today.

The Visual Ideal

Let’s see. Mimetic precision in depicting a human being. That would be like a Portrait, right? The spear carrier, the warrior, the discuss thrower—these would be depictions of distinctive representation of individuals’ appearance, right?

Actually, no. And the distinction is important. Artists in the classical Greek era did not strive to depict the appearance of individuals. They strove to capture an ideal of the human being. We use the word ideal pretty casually. In ancient Greece, the term derived from the work of Plato, a philosopher of incalculable influence. The ideal is …

“Platonic idealism” holds that real objects—a basket, a wagon, a horse, a man—are imperfect, flawed reflections of an Ideal Form beyond our experience: the perfect basket, wagon, horse, man. Classical Greek artists meticulously represented human anatomy, but they sought an ideal beauty beyond ordinary mortals: purity of line, balance, harmony, proportion.

|

| Doryphorus (Spear Carrier) detail |

The figure of the Spear Carrier is perfectly proportioned according to precisely calculated formulas of beauty. The size and arrangement of eyes in relationship to the larger head. The ratio of length of limb to width of shoulder and length of torso. As we will see, Renaissance artists discovered and committed themselves to these ideal proportions. Their ideas of the ideal human appearance continues to influence our assumed standards of personal beauty even today, sometimes to the detriment of our self-image and mental health.

The Spear Carrier is also, as I am sure you have noticed, nude. Attitudes of the Greeks toward the body differed from those of neighboring cultures. A key building in every polis was a palaestra, that is, a gym. Athletic workouts and competitions (e.g. the Olympics) were always performed in the nude. When a palaestra was established in a conquered city, the nudity often offended the conquered people. This was one of the reasons for the Jewish revolt against Seleucid (Greek) rule. Idealizing the male body, arts naturally presented them in the nude.

At this point, let’s just touch base with our notion of a classical approach to art. Order, serenity, completeness, fidelity to rules of appearance—these are precisely the characteristics that classicisms generally value. They require discipline and restraint. But you know it’s always difficult to restrain artists for long. The Classical always leads to reaction.

Hellenistic Art

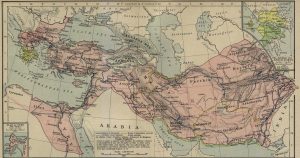

In the 4th Century BCE, the Macedonian/Greek king Alexander the Great avenged Greek peoples for earlier, failed invasions by the Persians and went on to conquer Asia Minor, Palestine, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and parts of India. After his death, Alexander’s authority descended into regional dynasties: Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Asia Minor, including the Palestine of the New Testament. Hellenistic Greek culture spread from India to North Africa.

|

| Map of Alexander’s Macedonian (Greek) Empire at its greatest extent |

The traditional distinction between Classical and Hellenistic art is controversial. (Scholars always argue over eras and movements.) Still, Hellenistic art moved beyond an idealized abstraction of beauty to engage human experience:

Consider the famous figure of Nike, the Greek name for the goddess of Victory. The figure doesn’t just stand in perfect contrapposto. It leans up and forward in a personification of Greek aspiration. In the figure, we see what Stansbury-Odonnell terms “a new kind of sensuality and refinement through transparent draperies that reveal the figure underneath and with intimate poses and situations.”

|

|

| Nike of Samothrace. (3rd-2nd Century BCE). Marble. | Venus de Milo. (c. 100 BCE). Frontal view. |

The figure of a half nude Venus, the goddess of love—Greek name, Aphrodite—was discovered in 1820 on the Greek island of Melios (Milos). One of very few Greek originals to survive, it is dated today to the 1st Century B.C.E. (Venus de Milo, 2004) and has become one of the most famous images of art on earth.

On its discovery, The Venus de Milo was thought to be the work of the late Classical master Praxiteles. Male nudes had long been common in Greek art, but Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos “inspired a whole series of naked or half-naked Aphrodites in Hellenistic art” (Osborne 231). The sculptural genre of a nude goddess of love inspired both fame and infamy in the ancient world as people were drawn to their sensuality but disturbed by their impropriety. An aesthetic[1] look at the figure perceives classical ideals of form and figure still powerfully influential in our contemporary notions of beauty.

Hellenistic art draws on classical conventions, but adds a taste for naturalism, i.e. depiction of the specific features of individuals, as well as a deeper embrace of drama and emotion. Consider the realism of the Boxer of Quirinal. Weariness. Pain. Scars. Tattered wrapping of the knuckles.

|

|

| Boxer of Quirinal. (c 75 BCE). Bronze Sculpture |

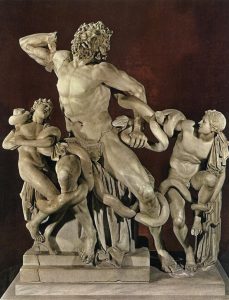

In Laocoön, Hellenistic art achieves an apotheosis.

|

| Laocoön. (50-25 BCE). Marble |

The Laocoön‘s intense emotionalism [was] influential on Baroque sculpture, and in the Neoclassical age … [was seen] by Winckelmann,[2] as a supreme symbol of the moral dignity of the tragic hero and the most complete exemplification of the “noble simplicity and calm grandeur” that he regarded as the essence of Greek art and the key to true beauty (Laocoön).

[1] As you will recall, an aesthetic perspective responds to formal aspects of design and sets aside ulterior motives such as, in this case, erotic impulses. Of course, aesthetic perspectives can be hard to maintain and can conflict with some ethical values.

[2] Winckelmann: Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) was a “German art historian and archaeologist, a key figure in the Neoclassical movement and in the development of art history as an intellectual discipline” (Winckelmann).

Vital Questions

Context

The Classical era of Greek philosophy and art has proven over 2,500 years to be one of the most influential in the world history of art. The Greek context is itself endlessly fascinating. But perhaps the most important contextual realization is the degree to which later contexts looked back to Classical Athens.

Perhaps the most central aspect of the Classical Greek context to take note of is its pioneering interest in philosophical abstraction. Greek thinkers, scientists, and artists willingly transcended religious and ideological interests to pursue truth and reality. For artists, this led to an innovative emphasis on the imitation of visual experience.

Content

“The imitation of visual experience.” As we have tried to see in this section, Classical Greek artists set out to analyze and reproduce the field of vision through which we perceive reality. Their compositions certainly reflected their own versions of ideological signification. But their commitment to accuracy in capturing visual experience itself set it apart from other ancient traditions. Classical Greek artists cared and strove to recreate the moment of vision and the illusion of seeing the “real thing.

Form

The most obvious aspect of Classical Greek representational technique is attention to imitative detail. A Classical sculptor strove to perfectly match anatomical details with incisions in stone.

But anatomical detail is only the beginning. Classical Greek artists conceptualized their figures in the dimensions of time and of space. A Greek sculpture was poised in time, its features composed to place muscles, limbs, balance points in the context of action. Next week, we will explore the way Renaissance painters would extend these commitments.

Finally, we should remember that Classical Greek artists composed their figures to reflect what they considered to be ideal qualities. Mathematical calculations governed the dimensional ratios of their figures’ components. Again, we will see how this compositional commitment influenced later artists such as Leonardo.

References

Akragas Painter. (c 440 BCE). Amazons, Mythical Warrior Women [Red Figure Pottery]. Athens, GR: National Archaeological Museum of Athens. IN Α 12492. https://www.namuseum.gr/en/monthly_artefact/female-valor-1-amazons-the-mythical-warrior-women/

Black-figure vase painting [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-286.

Borghese Warrior [Sculpture]. (c. 200 BCE) Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. MR 65 ; N 819; Ma 866. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010279164

Boxer of Quirinal [Bronze Sculpture] (c 75 BCE). Rome, IT: Palazzo Massimo alle Terme. Raddato, Carole. (February 8, 2014). Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boxer_of_Quirinal,_Greek_Hellenistic_bronze_sculpture_of_a_sitting_nude_boxer_at_rest,_100-50_BC,_Palazzo_Massimo_alle_Terme,_Rome_(13332767605).jpg

Diosphos Painter. (c 500 BCE). Terracotta neck-amphora. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. AN 256598. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/256598

Dipylon Vase. (8th century B.C.E.). Large funerary krater with scenes of ritual mourning (prothesis) and funeral procession of chariots. Athens, GR: National Archaeological Museum of Athens. https://www.namuseum.gr/en/collection/geometriki-periodos-3/

Diskobolos [Discus Thrower]. (Bronze original c. 450 BCE; marble copy circa 2nd century CE). Roman copy of a work by Myron. Rome, Italy: National Museum. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15999150

Doryphoros (Spear Thrower). [Statue]. (c 120-150 CE). Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/3520/the-doryphoros-copy-of-work-attributed-to-polykleitos Limestone Roman copy of Greek original.

Exekias. (6th Century BCE). Achilles Killing Penthelisea [Amphora]. London, UK: British Museum. RN 1849,0518.10. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1849-0518-10

Fowling Scene [Painting]. (c 1400 BCE). Luxor, E.G.: Tomb of Nakht. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548578

Greek and Phoenician Settlements in the Mediterranean, 550 BCE [Map]. (1911). In Shepherd, W. R. The Historical Atlas. https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/greek_phoenician_550.jpg

Halun, Jakub. (June 1, 2024). Acropolis from Philopappos Hill, Athens [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:View_of_the_Acropolis_from_Philopappos_Hill,_Athens,_20240601_1137_0117.jpg

Holberton. P. (2001). “Classicism.” In H. Brigstocke (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-563

Ideal. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-1192

King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and queen [Sculpture]. (2490-2472 B.C.). Boston, MA: Museum of Fine Arts. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/230/king-menkaura-mycerinus-and-queen?ctx=3672cc6f-0a30-490e-a7f0-41eda054e603&idx=5

Kore figure, known as Lady of Auxerre [Sculpture]. (c. 640-630 BCE). Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. MND 847; Ma 3098 https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010276874

Kouros figure. Attributed to Myron. [Sculpture]. (6th century BCE). Greece: National Museum of Archaeology. https://www.namuseum.gr/en/collection/archaiki-periodos/Laocoön. (50-25 BCE). Marble. Vatican: Vatican Museum.

Laocoön [Article]. (2015). Oxford, UK: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-1343?rskey=y59HDq&result=2

Laocoön [Sculpture]. (50-25 BCE). Rome: Vatican Museum. https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-pio-clementino/Cortile-Ottagono/laocoonte.html

Macedonian Empire, about 323 BCE [Map]. (1911). In Shepherd, W. R. The Historical Atlas. https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/macedonian_empire_336_323.jpg

Nike of Samothrace (“Winged Victory”). (ca. 190 B.C.E.). Paris: Musee du Louvre. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18125931

Osborne, R. (1998) Archaic and Classical Greek Art. New York: Oxford University Press. (Not web accessible).

Piot, Eugène. (1852). Parthenon [Salted paper print. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. AN 2006.158. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/2006.158

Pliny the Elder. (79 CE). Natural History. Book XXXV, Chapter 36. Bostock, J. Trans. Perseus Collection: Greek and Roman Materials https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:abo:phi,0978,001:35:36

Red-figure vase painting. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-2039.

Rhodes, F. R. (2012). Greek Art and Architecture, Classical. In N. Silberman (Ed.), The Oxford Companion To Archaeology. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 Dec. 2019, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199735785.001.0001/acref-9780199735785-e-0171

Riace Warrior Sculpture]. (c 450 B.C). Calabria, IT: Museo Archeologico di Reggio Calabria. https://www.museoarcheologicoreggiocalabria.it/bronzi-di-riace/ Galli, L. August 14, 2014). Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Riace_bronzes_-_Statue_A-_Ancient_Greek_warrior.jpg Bronze with silver and copper.

Shepard, W. R. (1923). Greek and Phoenician Settlements in the Mediterranean Basin. In Historical Atlas, p. 12. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 12. Retrieved from Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved from https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/greek_phoenician_550.jpg.

Stansbury-O’Donnell, Mark D. (2012). Greek Art and Architecture, Classical: Classical Greek Sculpture [Article]. Silberman, N. A. Ed. The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780199735785.001.0001/acref-9780199735785-e-0171

Venus de Milo [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-3625

Venus de Milo. (c. 100 BCE). Frontal view. [Sculpture]. Paris, France: Musée du Louvre. LL 299 ; N 527; Ma 399https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010277627

A) an exemplar of excellence in a particular genre or tradition; B) an aes-thetic that features clarity, order, balance, symmetry, reason, mathematical precision; C) the ancient tradition of art, literature, and philosophy from classical Greece and Rome

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

in the Euro-American tradition of education and scholarship, the study of the art, literature, and thought of ancient Greece and Rome (Latin)

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative

the suggestion of movement in the frame based on the viewer’s knowledge. E.g. a viewer looking at a painting of a car chase will expect the cars to be moving

art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

in visual art, a composition that represents a human subject as an individual, meticulously capturing physical or psychological likenesses

Classical Greek art: composition of a figure’s features according to principles of balance and proportion to realize the ideal human body

in visual art, a 2-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth. Line may be straight or curved, directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

in visual art, the distribution of visual weight or placement of elements to produce a sense of equilibrium

a correspondence between unlike elements that contributes to overall unity

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).