3.4 Songs of Love

from Paul & Linda McCartney. (1976). “Silly Love Songs.”

You’d think that people would have had enough of silly love songs

But I look around me

And I see it isn’t so

Some people want to fill the world

With silly love songs

And what’s wrong with that?

I’d like to know

Cos here I go againI love you, I love you

I love you, I love you, Ah, I can’t explain

The feeling’s plain to me

Now can’t you see?

Who doesn’t like a love song? And isn’t love the other side of a hero’s journey? The hero wins the battle and triumphs in finding true love, right? After all, the romantic comedy is one version of the hero’s journey.

Love’s Sweet Passion

Passionate love has a way of pervading the minds and hearts of most people. And art in all times and places reflects this all too human preoccupation. Consider these lines:

Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth—

for your love is more delightful than wine.

Pleasing is the fragrance of your perfumes;

your name is like perfume poured out.

No wonder the young women love you!

Take me away with you—let us hurry!

Let the king bring me into his chambers.

Recognize these lines? You may or may not be surprised to find that they are excerpted from the opening chapter of The Song of Songs, one of the books of the Ketuvim, the wisdom Writings of Hebrew scripture.

Song of Songs has often been interpreted as an extended metaphor of God’s love for His church. However, the text clearly celebrates sexual passion, that part of God’s creation that leads to renewed life. From ancient texts to Paul McCartney to contemporary rap music, the myth of love as a consuming passion has fueled poetic traditions throughout human history.

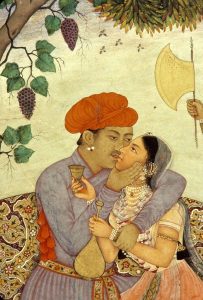

It has also, of course, inspired artists. In the 16th Century, the Mughal Empire in South Asia combined Mongol, Persian, and Indians cultural traditions. Its art was stylistically influenced by the Hindu tradition. On the other side of the Eurasian continent, Jean-Honoré Fragonard was conjuring frothy images of passion in the Rococo style.

|

|

| Lovers Embracing [Painting]. (c 1650). Mughal period art. | Jean-Honoré Fragonard. (c 1765). Happy Lovers. Oil on canvas. |

|

|

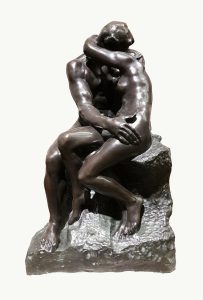

| Pierre-Auguste Renoir. (1875). Lovers. Oil on canvas. | Auguste Rodin. (1886). Kiss. Bronze Sculpture. |

In the 19th Century, European artists interpreted passion in the Impressionist and Romantic styles. We find here our first peeks at Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Auguste Rodin.

Star-Crossed Lovers

Of course, when people think of true love, they generally picture Romeo in the shadowed garden wooing Juliet on her balcony. This scene is so powerfully fixed in the global awareness that thousands of visitors flock to the Juliet balcony in Verona even though the lovers were mere fictions and the relationship of the house to the story is wholly fabricated. Something elemental ties that story to our passion-minded hearts.

William Shakespeare. from Romeo and Juliet (1587). Act 2, Scene 2

ROMEO But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the East, and Juliet is the sun.

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief

That thou, her maid, art far more fair than she.

Be not her maid since she is envious.

Her vestal livery is but sick and green,

And none but fools do wear it. Cast it off.

It is my lady. O, it is my love! …

Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven,

Having some business, do entreat her eyes

To twinkle in their spheres till they return.

What if her eyes were there, they in her head?

The brightness of her cheek would shame those stars

As daylight doth a lamp; her eye in heaven

Would through the airy region stream so bright

That birds would sing and think it were not night.

Juliet and Romeo have fallen instantly in love. However, they cannot approach each other because their families, the Montagues and the Capulets, have long been engaged in an often fatal feud. Juliet longs for love to transcend family conflict.

Deny thy father and refuse thy name,

Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love,

And I’ll no longer be a Capulet. …

’Tis but thy name that is my enemy.

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague.

What’s Montague? It is nor hand, nor foot,

Nor arm, nor face. …

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet.

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo called,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes

Without that title.

[1] Wherefore: this means why are you Romeo? Juliet wishes he were not the sone of her family’s feuding enemy.

|

| Eugène Delacroix (1845). Romeo and Juliet. Oil on canvas. |

As Romeo inches forward, Juliet senses his presence and the two swear their undying love.

JULIET What man art thou that, thus bescreened in night,

So stumblest on my counsel? …

Dost thou love me? I know thou wilt say “Ay,”

And I will take thy word. Yet, if thou swear’st,

Thou mayst prove false. … O gentle Romeo,

If thou dost love, pronounce it faithfully. …

ROMEO

Lady, by yonder blessèd moon I vow,

That tips with silver all these fruit-tree tops—

JULIET O, swear not by the moon, th’ inconstant moon,

That monthly changes in her circled orb,

Lest that thy love prove likewise variable.

ROMEO What shall I swear by?

JULIET Do not swear at all.

Or, if thou wilt, swear by thy gracious self,

Which is the god of my idolatry,

And I’ll believe thee. …

ROMEO O, wilt thou leave me so unsatisfied

JULIET What satisfaction canst thou have tonight?

ROMEO Th’ exchange of thy love’s faithful vow for mine.

JULIET I gave thee mine before thou didst request it,

And yet I would it were to give again. …

My bounty is as boundless as the sea,

My love as deep. The more I give to thee,

The more I have, for both are infinite.

Nurse calls from within.

I hear some noise within. Dear love, adieu. …

ROMEO O blessèd, blessèd night! I am afeard,

Being in night, all this is but a dream,

Too flattering sweet to be substantial.

Lyrical Passion

Ewan MacColl. (1957) The first time ever I saw your face.

The first time ever I saw your face

I thought the sun rose in your eyes

The moon and the stars were the gifts you gave

To the dark and empty skies, my love

To the dark and empty skies …

And the first time ever I kissed your mouth

I felt the earth move in my hands

Like the trembling heart of a captive bird

That was there at my command, my love

That was there …

And the first time ever I lay with you

And felt you heart so close to mine

I thought our joy would fill the earth

It would last till the end of time, my love

It would last till the end of time

The first time ever I saw your face

Your face, your face …

Ewan MacColl crafted one of the great 20th Century love songs in post-war Britain. In 1969, American soul singer Roberta Flack recorded her version of the song on her album, First Take. The song became world famous when Clint Eastwood included it in his hit film, Play Misty for Me. For people of a certain age today (like, well, me), this song crystallized the essence of passionate love.

Now, we cannot deal directly with music in this course. However, we do explore song lyrics which are, after all, poems. In ancient Greece, a lyric was a portion of verse from a drama that was accompanied by a lyre.

One way of thinking of lyrics is a matter of length: they tend to be shorter than, for example, odes and far shorter than verse dramas or epics. The relationship between lyric and song is more significant, though not all lyrics are accompanied by melodies. Indeed, the Irish poet William Butler Yeats named one of his collections of verse Words for Music Perhaps (1933)—notice that qualifier added by a poet who was not a musician.

Lyrics reflect on matters of the heart. As such, they often suggest a larger Story context. MacColl’s rumination on his lover’s face clearly reflects a powerful experience, but we know little about it. There is actually a back story involving singer Peggy Seeger, but the lyric’s focus on pure passion has no need for such matters.

Reading a Lyric Poem

Roberta Flack in a Clint Eastwood film. You can handle that, right? But what about a passionate lyric from the 17th Century? Sound scary? Many people feel intimidated by the prospect of reading a poem. They remember some English teacher nattering on about symbolic meanings that they can’t see.

What if I told you that you could learn to make sense of poems? It’s actually not that hard, especially if you use a common sense approach:

1. Read the poem out loud, listening for and feeling its rhythms and patterns of sound.

2. Read the plain sense of the poem: who is talking to whom about what?

3. Track patterns of sense and meaning that suggest deeper signification: i.e. themes.

Andrew Marvell. (1681). The Fair[1] Singer.

To make a final conquest of all me,

Love did compose so sweet an enemy,

In whom both beauties to my death agree,

Joining themselves in fatal harmony;

That while she with her eyes my heart does bind,

She with her voice might captivate my mind.

I could have fled from one but singly fair,

My disentangled soul itself might save,

Breaking the curled trammels of her hair.

But how should I avoid to be her slave,

Whose subtle art invisibly can wreath[2]

My fetters[3] of the very air I breathe?

It had[4] been easy fighting in some plain,

Where victory might hang in equal choice,

But all resistance against her is vain,

Who has th’advantage both of eyes and voice,

And all my forces needs must be undone,

She having gained both the wind and sun.

[1] Fair: the word fair was long used in a double sense in English verse. On the one hand, it referred to beauty. On the other, it distinguished a person of light hair and complexion from one with darker features. Here, it probably refers to beauty.

[2] Wreath: in modern spelling, wreathe would fit the rhyme scheme.

[3] Fetters: chains that bind

[4] Had: that is, would have been.

Did you apply our process for reading poetry? Did you read aloud, listening for and feeling rhythms? As you read these verses, what do you hear? I’ll bet you hear Rhyme. Each of these poems establishes a pattern for the sounds of each line’s final words. Can you hear them? I’ll bet you can.

Now here’s the thing. Rhyme appeals to the ear, but that’s only the beginning. In strong verse, every rhyme enhances Thematic signification. Consider these rhyming pairs: agree/harmony; bind/mind; save/slave; wreathe/breathe. These rhymes help us recognize the themes the poets mean to stress. Reading aloud, listening really does open the thematic depths of the poem.

In Step 2, we ask ourselves, what is the plain sense of the poem? Who is talking to whom about what? Marvell sketches a narrative moment in which he is captivated by a singer. I’ll bet you can identify the twin powers that, in combination, leave him helpless before the woman’s charms. Can you name them?

When one sees these powers in the woman, the 3rd step is a short one. Marvell feels passion on two levels, but, thematically, the experience opens a reflection on different dimensions of beauty. Often, one can take a short step from the lyric’s specifics into a larger thematic generalization about life. Make sense?

This poem is 400 years old. Yet can we not relate to it? How many of us are overpowered by the dual appeal of great singers, actors, dancers, and athletes? How much has passion changed in 400 years?

Love’s Ideal

Marvell finds himself stumped by the same challenge faced by human beings throughout the ages. Love has at least two sides: the sensual and the inspirational. 17th Century English lyrics were known for composing sensual, almost erotic verse. But they and other poets also cultivate an Idealized, transcendent vision of love’s passion. Love can ennoble and elevate mind and heart. It can open the channel to spiritual grace. Let’s sample expressions of idealized passion.

Courtly Love’s Ideal

The history of the courtly love tradition is long and complex. For now, let’s just say that medieval knights in an intensely Catholic society sought ways to idealize and sanctify their predatory lifestyle of violence, plunder, and rape. The church developed rituals of sanctification thought to confer on warriors a secular version of the exalted spirituality attributed to monks and priests. An idealized ideal of life called courtesy conferred on the warrior class a veneer of generosity, manners, piety, and chastity.

Itinerant bards and troubadours made a living singing heroic tales and love songs in aristocratic courts. Courtly Love songs envisioned love as a spiritually exalting, purifying ideal that emulated saintly chastity by addressing an unobtainable woman, often a wife of a liege lord. The song indulges in grandiose celebration of the beloved’s beauty and virtues and sensationally bemoans the ennobling misery of a broken heart, often characterized as a form of death for the Persona.

In courtly love verse, the lover is often a vassal who flatters the wife of a liege lord, a woman whom he obviously cannot touch. The lover flirts with the beloved, undertaking missions, expressing passionate adoration, but emulating monastic chastity by keeping hands off. Thus, courtly love verse teems with extravagant praise and love-sick suffering.

Love in English Queen Elizabeth’s court

By the 17th Century, courtly love verse had become a favorite game among members of the court of England’s Queen Elizabeth I. Courtiers competed with each other for top honors in composing love poems of surpassing wit and flattery.

Sir Philip Sidney (1591). Astrophil and Stella, Sonnet 48

Soul’s joy, bend not those morning stars from me,

Where virtue is made strong by beauty’s might,

Where love is chasteness, pain doth learn delight,

And humbleness grows one with majesty.

Whatever may ensue, O let me be

Co-partner of the riches of that sight;

Let not mine eyes be hell-driv’n from that light;

O look, O shine, O let me die and see.

For though I oft my self of them bemoan,

That through my heart their beamy[1] darts[2] be gone,

Whose cureless wounds even now most freshly bleed,

Yet since my death wound is already got,

Dear killer, spare not they sweet cruel shot;

A kind of grace it is to slay with speed.

[1] Beamy: rich with beams of light

[2] Darts: i.e. arrows

One of the finest courtly love practitioners in Elizabeth’s day was Sir Philip Sidney who composed a Sonnet sequence of 119 poems bewailing the poet’s love for an unattainable woman. The collection was entitled Astrophil and Stella, a pair of fictive names testifying to an idealized passion. In Latin, Stella means star. You may be able to guess that Astrophil breaks down into star lover. This passion has celestial dimensions.

Can you apply our process for reading poems to Sidney’s lyric? Read aloud first. Listen for the Rhymes and let them guide you to the breaks between Stanzas. We might notate the rhymes thus: a-b-a-b//a-b-a-b//c-c//d-e-d-e. We get four stanzas: quatrain (4 lines) quatrain, couplet (2 lines) and quatrain.

Now how can these rhymes help us process the poem’s Themes? Lines 1-8 share the same rhyming pattern. Then, something seems to shift in line 8. How does the mood change at that point? How does this shift fit in with the courtly love convention of passion’s Idealized, exalting, exquisitely miserable yearning?

“Somewhere Beyond the Sea”: Love’s Ideal

Idealized love. Love-sickness. Despair over the unobtainable beloved. Sound familiar? It should. These courtly love ideals have long persisted: “the sufferings of lovers, love as sickness or war, secret love, love at first sight, the (so-called) idealization of woman, these themes constitute the repertoire of amorous fiction up to our own time” (Blumenfeld-Kosinski). Think of Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan in Sleepless in Seattle finding Idealized love though separated by an entire continent. Our love longs and stories are drenched in courtly loves’ idealizing dynamics of passion.

In 1945, Charles Tenet and Jack Lawrence composed one of many popular songs inspiring soldiers, sailors, and civilians struggling to survive the carnage of World War II. What ideal does love seem to offer one seeking an escape from a daunting reality?

Charles Tenet and Jack Lawrence, (1945) “Beyond the Sea”

Somewhere beyond the sea

somewhere waiting for me

my lover stands on golden sands

and watches the ships that go sailin’

Somewhere beyond the sea

she’s there watching for me

If I could fly like birds on high

then straight to her arms

I’d go sailin’

It’s far beyond the stars

it’s near beyond the moon

I know beyond a doubt

my heart will lead me there soon

We’ll meet beyond the shore

we’ll kiss just as before

Happy we’ll be beyond the sea

and never again I’ll go sailin’

I know beyond a doubt

my heart will lead me there soon

We’ll meet (I know we’ll meet) beyond the shore

We’ll kiss just as before

Happy we’ll be beyond the sea

and never again I’ll go sailin’

No more sailin’

so long sailin’

bye bye sailin’…

This composition really is a song lyric. You may find it more attractive to listen to a pop song than to read aloud 400- or 500-year-old poetry. One of the most well-known renditions of the tune became a signature hit for Bobby Darin (YouTube link).

|

| Bobby Darin (11 March 1959). Publicity photo. |

This is not, strictly speaking, courtly love verse. However, the lyric shares the Idealized view of love Conventional in that tradition. The lyric yearns for a love, not connected to a specific person, which appeals directly to our unquenchable hope for a life beyond the petty limitations of our world. Somewhere, someday, somehow one will find a bridge to a world with golden sands and a dream lover who delivers one from the perpetual striving and seeking of life.

Let’s keep in mind the context in which this song was composed and celebrated. It was originally composed in France and later embraced in English by a generation which had known the miseries of the Depression and the unimaginable horror of World War II. Nevertheless, “I know beyond a doubt,” insists the song’s Persona that one day, “Happy we’ll be beyond the sea/and never again I’ll go sailin.’”

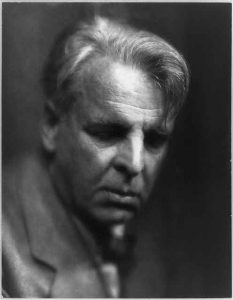

William Butler Yeats, Celtic Troubadour

|

| Portrait of William Butler Yeats. (Feb. 7, 1933) Photographic print |

The Anglo-Irish poet William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) steeped his work in Celtic traditions, contemporary Irish experience and his own reflections on mortality and the heart. At 24, Yeats met Maud Gonne, a powerful woman passionately committed to Irish independence. Yeats fell deeply in love with Gonne and was haunted by her rejection of him. Her aura pervades his verse, often embodied in the apple blossoms he recalled from their first meeting. How does Yeats use Rhyme scheme and Stanzas to pace the fanciful story and develop his themes of love?

William Butler Yeats (1899) “The Song of the Wandering Aengus”

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.

When I had laid it on the floor

I went to blow the fire a-flame,

But something rustled on the floor,

And someone called me by my name:

It had become a glimmering girl

With apple blossom in her hair

Who called me by my name and ran

And faded through the brightening air.

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done,

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

Yeats’ early verse drew heavily on Celtic myths: “Angus Óg is the god of youth and beauty among the Tuatha Dé Danann; he may also be the god of love, if any such god can be said to exist” (Angus Óg). Yeats finds inspiration in the association of Aengus with poetry and with “a widely known story” of Angus Óg “wasted by longing for a beautiful young woman he has seen only in a dream.”

Domestic Love

Passionate love. Ideal love. Perhaps the richest, if quietest, love is domestic. As Tolstoy observed in the opening lines of Anna Karenina, some families are happy and some aren’t. Family structures differ enormously in cultures around the world. Yet every culture seems to develop its ideal notion of a family.

A wife of noble character who can find?

She is worth far more than rubies.

Her husband has full confidence in her

and lacks nothing of value.

She brings him good, not harm,

all the days of her life.

She selects wool and flax

and works with eager hands.

One cultural tradition which has influenced the familial models of many others is that of the ancient Hebrews. Jewish, Christian, and Muslim cultures all look back to the family structure modeled by Abraham, Sarah, and Leah. Abraham’s example was clearly patriarchal, but Hebrew tradition did honor the role of the woman. The Proverbs writer employs rich poetic rhythms to celebrate the wisdom and strength of an ideal wife. By now, you can recognize those figurative rhythms, right?

Love in New England

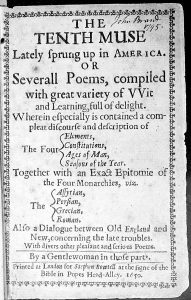

Anne Bradstreet found her way into print by a most improbable route. A child of non-conformist parents, Bradstreet married a man who shared her Puritan convictions and emigrated with him to the new Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. She wrote numerous poems which were published in England in 1650 as a remarkable instance of verse arising in the American wilderness and composed by a woman, a genuine wonder in the mind of the culture. Bradstreet’s most well-known poem is “To My Dear and Loving Husband,” a passionate and loving tribute to the love she and her husband shared and their hope for an eternal union.

|

| The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. Frontispiece: 1st edition image |

Anne Bradstreet. (1650). “To My Dear and Loving Husband”

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were loved by wife, then thee.

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me, ye women, if you can.

I prize thy love more than whole mines of gold,

Or all the riches that the East doth hold.

My love is such that rivers cannot quench,

Nor ought but love from thee give recompense.

Thy love is such I can no way repay;

The heavens reward thee manifold, I pray.

Then while we live, in love let’s so persevere,

That when we live no more, we may live ever.

Victorian Love

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was hailed as one of the finest poets of the Victorian age, although at the time the praise was generally qualified: one of the finest female poets. In 1846, she was contacted by Robert Browning, a young poet impressed by her work. The two poets enjoyed a long, loving marriage.

|

| Michele Gordigiani. (1858). Portrait of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Daguerreotype. |

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. (1850). Sonnet #43

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850) was an exercise in the tradition we have just sampled: the sonnet sequence. As you read the sonnet, let the Rhyme Scheme guide you to its thematic structure. How are the Stanzas laid out? Where is the thematic Turn? Can you tell if this is an Italian or Shakespearian sonnet?

As you try to process the sonnet, be clear on its plain sense. Remember: we always need to be clear on who is talking to whom about what? Be aware of the text’s dynamic stretching between two identities: the Persona, or voice of the poet, and her beloved husband. How does Browning celebrate her marriage by exploring themes in a Catalogue of dimensions: soul, freedom, purity, passion, time, faith, and spirit?

Maternal Love under Duress

When we think of domestic love, we often think first of love between spouses. Yet few themes carry more weight than that of a mother for her child. A mother’s steadfast love gains even more power when it stands strong in the face of challenges.

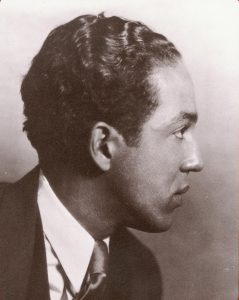

In 1902, Langston Hughes was born in Joplin Missouri in a mixed heritage steeped in a tradition of education and ethnic pride. We will meet Hughes again in his role as a leader in the so-called Harlem Renaissance.

|

| Allen, James L. (1930). Portrait of Langston Hughes. Photograph. |

Langston Hughes (1926) “Mother to Son”

Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor—

Bare.

But all the time

I’se been a-climbin’ on,

And reachin’ landin’s,

And turnin’ corners,

And sometimes goin’ in the dark

Where there ain’t been no light.

So boy, don’t you turn back.

Don’t you set down on the steps

’Cause you finds it’s kinder hard.

Don’t you fall now—

For I’se still goin’, honey,

I’se still climbin’,

And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

For now, let’s read his powerful poem celebrating the steadfastness by which an enduring mother tries to instill courage and perseverance in the mind of a son tempted by waywardness walking the hard road of racist America. This advice takes on extra force when we understand that Hughes’ father, frustrated by America’s hostile environment, emigrated to Mexico, leaving his wife and son behind to make their way.

Vital Questions

Do we ever tire of silly love songs? Probably not. We could, of course, sample love songs for weeks, drawing from scores of cultural traditions. Our selections, diversely sourced as they are, share influence in the cultural traditions that shaped Europe and the Americas.

Context

In a strict sense, the world of courtly love verse is long gone. Yet its notion of passionate love as an ideal, exalting force continues to influence, for good and for ill, our view of loving relationships. Productions of Romeo and Juliet continue to abound. Pop songs. Romantic comedies. Romance novels. Bollywood musicals. Telenovelas. Valentine’s Day greeting cards. All of these traditions affirm the unsurpassed value of passionate true love. The sensitive and the faithful search for “the one” selected by “the universe” to fulfill a life that cannot be otherwise complete.

Content

Obviously, any love story pits a lover and a beloved against each other. Or, in the case of a love triangle, two competitors seeking a beloved’s affections. The agon in such stories boils down to two questions. Do lover and beloved share love? And, if so, where will it lead?

Often, the answer to the first question is no. Love goes unrequited. And, really, a great deal of what we think of as falling in love occurs in the solitude of the lover’s imagination and heart. For this reason, love stories are particularly appropriate for lyric poems and songs. The private, introspective nature of the lyrical voice gazes inward, seeking an answer that cannot lie within but must come from the beloved. Courtly love lyricists speak for many a lover whose fancies yearned for the beloved’s kiss but never find it.

Form

We must always be cautious when approaching poetry in translation. It is ultimately impossible to read aloud and listen for sound rhythms in a poem composed in a different language from our text.

At this point, however, we are beginning to sample poetry from the English tradition. We can begin to use our ears and sense of verbal rhythm to respond to the patterns that comprise verse. We have not yet delved deeply into matters of English prosody. But we are just sampling core notions of English verse:

Rhyme: a pattern of repeated sounds, usually the final syllable in the ends of verse lines

Stanza: a division of the poem rather like a prose paragraph a division of within a poem that functions as does a prose paragraph and organizes the poem’s themes. Stanzas are labelled according to their number of lines and are often, but not always, defined by …

Rhyme schemes: a repeated pattern of sounds that end lines, defining stanzaic boundaries and shaping a poem’s themes

Sonnets: a 14-line lyric poem that explores a theme in stanzas with a thematic turn.

Stay tuned!

References

Allen, J. L. (1930). Langston Hughes. [Photograph.]. New York, NY: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. https://www.nypl.org/support/planned-giving/langston-hughes-society

Bobby Darin [Publicity photo]. (11 March 1959). Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bobby_Darin_1959.JPG.

Darin, B. (1959). Somewhere beyond the sea [Song]. That’s All. Atco Records. YouTube recording https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FO4I-0DGAn4

Bradstreet, A. (1650). “To My Dear and Loving Husband.” In The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. Retrieved from https://www-fulcrum-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/epubs/cv43nx03m?locale=en#/6/526[xhtml00000263]!/4/1:0.

Bradstreet, A. (1650). Frontispiece. The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Tenth_Muse_by_Anne_Bradstreet.jpg

Browning, E. B. (n.d.). Sonnets from the Portuguese 43: How do I love thee me count the ways. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43742/sonnets-from-the-portuguese-43-how-do-i-love-thee-let-me-count-the-ways.

Couder, Auguste. (1821). Romeo and Juliet [Painting]. Angers, FR: Musée des beaux-arts. AN ART149536. https://ow-mba.angers.fr/fr/notice/1996-37-1-scene-de-romeo-et-juliette-de-shakespeare-une-97ccbeec-b479-40f7-83b3-65e1197d7669

Darin, B. (1959). Somewhere beyond the sea [Song]. That’s All. Atco Records. YouTube recording https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FO4I-0DGAn4

Delacroix, E. (1845). Romeo and Juliet [Painting]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Delacroix_-_The_farewell_of_Romeo_and_Juliet,_1845.jpg

Flack, R. (1969). The first time ever I saw your face [Song]. First Take. Atlantic Records. Listening to Music https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kAdDZquvFKc

Fragonard, Jean-Honoré. (c 1765). Happy Lovers [Painting]. Pasadena, CA: Norton Simon Museum of Art. https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/F.1965.1.021.P

Gordigiani, Michel. (1858). Portrait of Elizabeth Barrett Browning [Painting]. London, UK: National Portrait Gallery. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw00856/Elizabeth-Barrett-Browning?LinkID=mp07024&role=art&rNo=0

Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version. (2021). Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-Revised-Standard-Version-Anglicised-NRSVA-Bible/#booklist

Hughes, Langston. (1926). “Mother to Son.” In The Weary Blues. New York: Knopf. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47559/mother-to-son.

Lawrence, Jack and Tenet, Charles. (1945). “Beyond the Sea. Retrieved from https://lyricsplayground.com/alpha/songs/b/beyondthesea.html.

Lovers Embracing [Painting]. (c 1650). Mughal period art. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. AN 6786. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1971.91

Marvell, A. (1681). The Fair Singer. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44681/the-fair-singer

McCartney, P. and L. (1976). “Silly love songs” [Song]. Wings at the Speed of Sound. London, UK: Abbey Road Studios. Lyrics.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 20 Jun 2024. https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/32861538/Paul+McCartney/Silly+Love+Songs

MacColl, E. (1957). The first time ever I saw your face [Song]. Lyrics.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 20 Jun 2024. https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/2394131/Ewan+MacColl/The+First+Time+Ever+I+Saw+Your+Face

Renoir, P. A. (1875). Lovers [Painting]. Prague, Czech Republic: National Gallery. https://sbirky.ngprague.cz/en/dielo/CZE:NG.O_3201

Rodin, A. (1886). Kiss [Sculpture]. Warsaw, PO: National Museum in Warsaw. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rodin_The_Kiss_01.jpg

Shakespeare, W. (1597). Romeo and Juliet. (B. Mowat, P. Werstine, M. Poston, and R. Niles, eds.). The Folger Shakespeare. https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/romeo-and-juliet/read/

Sir Philip Sidney (1591). Sonnet 48. Astrophil and Stella. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50078/astrophil-and-stella-48-souls-joy-bend-not-those-morning-stars-from-me

Yeats, William Butler. (1899). “The Song of the Wandering Aengus.” In The Wind Among the Reeds. London: Elkin Mathews. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/55687/the-song-of-wandering-aengus.

a connected series of events and actions that play out in a world projected by a narration

a pattern of repeated sounds, usually the final syllable in the ends of verse lines

In the arts, a representation of some aspect of experience that is raised above the mundane to exemplify a higher, more perfect plane of existence. E.g. the chaste, idealized model of love depicted in the Courtly Love tradition

the voice, identity, and point of view to which we attribute a literary text. In ancient Greek, the mask worn by actors on stage.

a 14-line lyric poem that explores a theme in stanzas with a thematic turn either between lines 8 and 9 (Petrarchan/Italian Sonnet) or between lines 12 and 13 (Shakespearian/English Sonnet).

a division of within a poem that functions as does a prose paragraph and organizes the poem’s themes. Stanzas are labelled according to their number of lines and are often, but not always, defined by rhyme schemes.

a pattern of thought, value, and reflection which signifies meaning beyond the specifics of the content in a work of art

a Medieval poetic tradition deriving from Arab verse and 12th Century French troubadours in which a poetic voice proclaims a spiritually exalted, chaste love for an unattainable beloved, often the wife of the lover’s liege lord (feu-dal master). A conception of transcendent sexual love that remains influential in modern culture and its arts.

an aspect of art which is expected and understood by the audience in a particular tradition

within a poem, a repeated pattern of sounds that end lines, defining stanzaic boundaries and shaping a poem’s themes. Designated for analysis by letters: e.g. a-b-a-b, in which a-lines and b-lines end in rhyming words.

in a Sonnet, a thematic shift, often a contrast, between the themes of the earlier and closing stanzas

a rhetorical figure that rhythmically lists examples of a category to build in-tensity and emphasis. Common in epic poetry and in free verse in the tradition of Walt Whitman