2.6 Wisdom Literature

Torah is followed in the Hebrew canon of texts by Nevi’im (Prophets). The earlier books of the prophets, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, continue in prose narrative the saga of the Jewish people in Canaan and later in Babylonian captivity.

As we move on to famous later prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Amos, and the rest things change. The texts focus more sharply on the orations of the prophet and are presented in verse format. In a sequence that differs from that of the Christian Old Testament, the Ketuvim (Writings) come last: Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, The Song of Solomon, Job etc. Most of these texts, often referred to as Wisdom Literature in the Christian tradition, are also composed in verse form.

Many people who read the Psalms or Proverbs for their spiritual wisdom don’t notice the verse form. Indeed, the old King James Version of the bible presented these texts as prose. Even reading modern translations which honor the verse forms, it’s easy to overlook the poetic element. Well, let’s try it. Read the 13th Psalm aloud. Listen for, feel the rhythms. Do you hear them?

Psalm 13. a Psalm of David– Prayer for Deliverance from Enemies

How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?

How long will you hide your face from me?

How long must I bear pain in my soul,

and have sorrow in my heart all day long?

How long shall my enemy be exalted over me?

Consider and answer me, O Lord my God!

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep the sleep of death,

and my enemy will say, “I have prevailed”;

my foes will rejoice because I am shaken.

But I trusted in your steadfast love;

my heart shall rejoice in your salvation.

I will sing to the Lord, because he has dealt bountifully with me (Psalm 13).

|

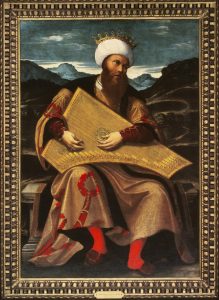

| Girolamo da Santa Croce. (c 1540-50). King David. Oil on canvas. |

The audio recording above may help you hear the poetic rhythms of David’s song. You won’t hear Rhyme or even Meter. The rhythm is found in patterns of ideas and syntax. You will remember that Gilgamesh displayed the same, virtually universal Figures of speech:

- Scheme: repeated patterns of expression that enhance the rhetorical effect of the text

- Anaphora: a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses

- Parallelism: a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms:

If you pay attention to the opening phrases in lines and their syntactic (grammatical) structures, you’ll begin to hear the verse. Rhythm is always about repetition. Rhetorical patterns of expression support repetitions of ideas. Not only do we tend to remember concepts that are stated and restated, but we become caught up in the rhythmic flow. Let’s listen for the rhythms in the opening passage from the Book of Proverbs.

Call of Wisdom

Wisdom cries out in the street; in the squares she raises her voice.

At the busiest corner she cries out;

at the entrance of the city gates she speaks:

“How long, O simple ones, will you love being simple?

How long will scoffers delight in their scoffing and fools hate knowledge?

Give heed to my reproof;

I will pour out my thoughts to you; I will make my words known to you.

Because I have called and you refused, have

stretched out my hand and no one heeded,

and because you have ignored all my counsel and would have none of my reproof,

I also will laugh at your calamity; I will mock when panic strikes you,

when panic strikes you like a storm, and your calamity comes like a whirlwind,

when distress and anguish come upon you.

Then they will call upon me, but I will not answer;

they will seek me diligently, but will not find me.

Because they hated knowledge and did not choose the fear of the Lord,

would have none of my counsel, and despised all my reproof,

therefore they shall eat the fruit of their way and be sated with their own devices.

For waywardness kills the simple, and the complacency of fools destroys them;

but those who listen to me will be secure

and will live at ease, without dread of disaster” (Proverbs 1.20-33).

|

| Paolo Veronese. (c 1580). Allegory of Wisdom and Strength. Oil on canvas. |

Rhetoric of the Ages

Did you notice something a bit odd? We recognized certain rhetorical patterns in a Sumerian epic composed in cuneiform on clay tablets. Then we found those same rhythms composed in Hebrew script on papyrus sheets many centuries later. Isn’t it strange to find this convergence?

Well, not really. These rhetorical figures are common to compositions in languages around the world over thousands of years. They are common today in the orations of preachers, politicians, lecturers and activists. Go to church this week and listen carefully to the sermon. If the speaker is skilled, you’ll hear them creating the sonorous flow of eloquence.

Let’s look at one example of a speech that has had an enormous impact on our world. Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I have a Dream” speech reverberates with parallelism and anaphora.

Dr. Martin Luther King, August 28th, 1968

I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out … its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and … of former slave owners will … sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, … of oppression, will be … an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, … one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

… This is our hope, and this is the faith. …

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day — this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning:

My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride,

From every mountainside, let freedom ring! …

And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that:

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last

|

| Adelman: Dr. King’s “I have a dream” speech (August 28, 1963) |

Vital Questions

Context

Sampling Sumerian and Hebrew narratives side by side, we encounter remarkable similarities and distinctive differences. Jewish culture had its roots in the Mesopotamian world but it broke away and forged its own distinctive way. For Jews, for Christians, and for Muslims, the story of Abraham lies at the core of their spiritual traditions. When Abraham and his family turned away from the worship of many gods to a living relationship with Jehovah, the river of religion veered sharply into a new course. As we will see, art in the Mediterranean, European, and American worlds veered with it.

Content

Our all-too-brief sampling of Hebrew scripture begins to sensitize us to the dimensions of one of the world’s most pervasive art forms: narrative. We will have much more to learn about how narrative works. For now, though, let’s emphasize a couple of things:

- Narrative—story-telling—is the communication of a story

- Story consists of a set of events which are projected into a time and place by …

- Narration is the voice or medium presenting the story.

As we will see, the dynamics of the relationships between these nodes are complex and deeply intertwined with meaning.

Form

As we have just begun to explore the dimensions of narrative, so we have poked a tentative toe into the sea of verse form. Today, people tend to shy away from poetry, although they lustily sing along to the lyrical verse that comprise their favorite songs. The fact is, however, that world literatures always begin with poetry and only modulate into prose as writing traditions establish themselves.

Despite its seminal significance in every culture’s artistic traditions, it can be very hard to carry poetry across the cultural divide. We can directly grasp an image of Isis, Devi, or Raven. But Gilgamesh and the Psalms must be translated. And translators will tell us that verse is almost impossible to translate fully: one must not only find counterparts for ideas, but one must then try to imagine how to parallel the poetic rhythms of the origin language in one with wholly different sounds, rhythms and structures.

One dimension of poetic form that does tend to cross the context gap is figurative language. All cultures have their own forms of anaphora, parallelism, and catalogue, rhetorical forms shared by Gilgamesh and by rap masters in our own day. As we continue our journey, keep an eye out for rhetorical rhythms in verse and also in narrative!

References

Adelman, Bob. (1963). Martin Luther King at March on Washington DC. 1963. [Photograph]. New York, NY: Bob Adelman, Westwood Gallery. https://westwoodgallery.com/artists/45-bob-adelman/works/594-bob-adelman-the-dreamer-dreams.-washington-d.c.-1963-printed-2007/

da Santa Croce, G. (c 1540-50). King David. [Painting]. Chicago, IL: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago. https://smartcollection.uchicago.edu/objects/2566/king-david?ctx=85f04905ea12a1f7e22614fd032e553adbdb9926&idx=0

Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version. (2021). Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-Revised-Standard-Version-Anglicised-NRSVA-Bible/#booklist

Molnár, J. (1850). Abraham’s Journey from Ur to Canaan [Painting]. Budapest, Hungary: Hungarian National Gallery. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Moln%C3%A1r_%C3%81brah%C3%A1m_kik%C3%B6lt%C3%B6z%C3%A9se_1850.jpg

Fetti, Domenico. (1617). Moses and the Burning Bush. [Painting]. Vienna, AU: Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, inv. GG 165. https://www.khm.at/en/artworks/moses-before-the-burning-thorn-bush-690

Signorelli, L. and della Gatta, B. (c 1482). Testament and Death of Moses [Fresco]. Vatican: Sistine Chapel. Web Gallery of Art https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/s/signorel/sistina/moses.html

Veronese, P. (c 1850). Allegory of Wisdom and Strength [Painting]. New York, NY: The Frick Collection. AN 12.1.128. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/paolo-veronese/allegory-of-wisdom-and-strength-the-choice-of-hercules-or-hercules-and-omphale-1584

a pattern of repeated sounds, usually the final syllable in the ends of verse lines

a disciplined pattern of sound units throughout the lines of a poem. In English verse, meter is found in the number and a pattern of stressed and un-stressed syllables in a line