2.2 Sumerian Cuneiform: Accounting and Literature

2.2 Sumerian Cuneiform: Accounting and Literature

About 5,000 years ago, settlements in the lush lands between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (today, Iraq) developed an abundant level of prosperity and population. By this time, people were living in fixed settlements all over the world. Yet archaeologists refer to the “Uruk phenomenon,” the development among Sumerians of the first (?) settlement which we might call a city.

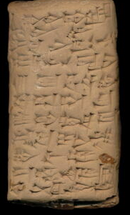

Cities, of course, require economic prosperity. The flood plain of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the Fertile Crescent, allowed the Sumerians to gather and store surpluses of grain substantial enough to sustain trade with people throughout the region and into Egypt. Now, once you have a surplus, you must keep track of it. The Sumerians developed an accounting system that recorded storage levels and trade transactions by means of marks incised on small clay tablets: cuneiform.

|

|

|

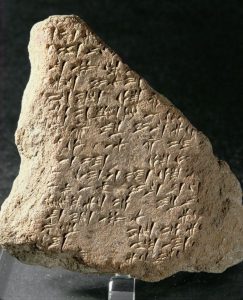

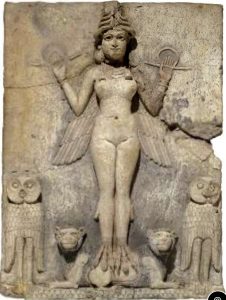

| Tablet with cuneiform. (c 626-539 BCE). | Epic of Gilgamesh, fragment [Cuneiform tablet]. (15th C BCE). | Gilgamesh and Enkidu Killing Humbaba. [Terracotta relief). (2nd millennium, BCE). |

In time, this accounting method developed into a general system for writing. In about 2,500 BCE, a mythic story was recorded concerning the heroics of a Sumerian king of Uruk. His name was Gilgamesh. As far as we know, this was the world’s first literary narrative.

Epic Tale of Gilgamesh

from Tablet 1

He who has seen everything, I will make known (?) to the lands.

I will teach (?) about him who experienced all things….

Anu[1] granted him [i.e. Gilgamesh] the totality of knowledge of all.

He saw the Secret, discovered the Hidden,

he brought information of (the time) before the Flood.

He went on a distant journey, pushing himself to exhaustion,

but then was brought to peace.

He carved on a stone stela all of his toils,

and built the wall of Uruk-Haven,[2]

the wall of the sacred Eanna Temple,[3] the holy sanctuary.

Look at its wall which gleams like copper(?),

inspect its inner wall, the likes of which no one can equal!

Take hold of the threshold stone–it dates from ancient times!

Go close to the Eanna Temple, the residence of Ishtar,[4]

such as no later king or man ever equaled!

Go up on the wall of Uruk and walk around,

examine its foundation, inspect its brickwork thoroughly.

Is not (even the core of) the brick structure made of kiln-fired brick? …

Supreme over other kings, lordly in appearance,

he is the hero, born of Uruk, the goring wild bull.

He walks out in front, the leader,

and walks at the rear, trusted by his companions.

Mighty net, protector of his people,

raging flood-wave who destroys even walls of stone!

Offspring of Lugalbanda,[5] Gilgamesh is strong to perfection,

son of the august cow, Rimat-Ninsun;[6] … Gilgamesh is awesome to perfection.

It was he who opened the mountain passes,

who dug wells on the flank of the mountain.

It was he who crossed the ocean, the vast seas, to the rising sun,

who explored the world regions, seeking life. …

Who can say like Gilgamesh: “I am King!”? …

Two-thirds of him is god, one-third of him is human.

The Great Goddess [Aruru][7] designed(?) the model for his body,

she prepared his form …

… beautiful, handsomest of men.

[1] Anu: Sumerian sky deity, lord and ancestor of other gods

[2] Uruk-Haven: the Sumerian city-state of Uruk, a pioneer Mesopotamian city-state

[3] Eanna Temple: Sumerian temple in the city-state of Uruk, devoted to and the residence of the goddess Inanna (or Ishtar).

[4] Ishtar: a later name for Inanna, goddess of love, sex, beauty, war, and power

[5] Lugalbanda: a king of Uruk

[6] Rimat-Ninsun: Sumerian cow goddess and, according to the epic, mother of Gilgamesh

[7] Aruru (or Ninḫursaĝ ): a Sumerian mother goddess of fertility

Among mythic tales, epics are extended narratives that celebrate heroic deeds which exemplify a culture’s values. The Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest known recorded epic, almost certainly a literary transcription of long-established oral traditions. Gilgamesh survives today on fragile cuneiform tablets—time’s erosion inevitably leaves blank spots in the text, indicated by the translator. These tablets weave a tale that in translation comprises about 50 pages.

In our first 40 lines, we see the characteristics of a patriotic myth. The lines credit Gilgamesh with having “built the wall of Uruk-Haven.” Obviously, he personifies the community which has erected mighty walls that civic pride compares disdainfully to those of lesser settlements. In a culture dependent on a vast irrigation network, he has “dug wells on the flank of the mountain.” Gilgamesh embodies community prosperity, power, and prestige.

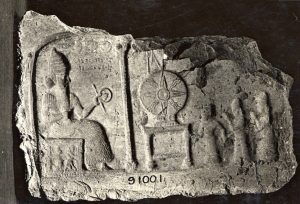

Prosperity, power, prestige—these arise from hard work. But also, for any ancient people, the favor of the gods. As we saw in our last sections, the role of leader in an ancient culture was to personally mediate between the people and the gods. Like many ancient royals, Gilgamesh is seen as part divine, son of the Cow Goddess Rimat-Ninsun. He is expected to maintain contact and influence on the gods who shaped the people’s destiny. If the city’s prosperity ever fails, it will be assumed that Gilgamesh has lost his divine patronage.

|

|

|

| Rimat-Ninsun (c 2150 BCE) | Enanna/Ishtar. (c 2025-1763 BCE) | Shamash protecting King Nabu-apla-iddina. (c 860 BCE). Clay relief. |

Thus Gilgamesh builds not only the city walls, but also “the wall of the sacred Eanna Temple, the holy sanctuary,” A Mesopotamian city was associated with a particular divine patron, in the case of Uruk, Eanna, also known as Ishtar. As we have seen, divine patrons were thought to actually dwell in their temples. As long as the god remained in residence, all would be well. A city that suffered from drought or disease or conquest immediately understood that the god would have departed from the temple and from the city.

an extended, mythic narrative celebrating the trials and triumphs of heroes exemplifying a culture’s treasured values and orienting its origins