1.5 Formline Style

Art of the Pacific Northwest

Stylized Art. Is this concept making sense? Let’s take a brief look at an age-old artistic tradition that displays one of the most stylized aesthetics one can find.

Fans of American football are familiar with the distinctive design of the Seattle Seahawks logo. They may not realize that it emulates the style shared by peoples of the Pacific’s Northwest Coast: the Haida, Tlingit, Kwakiutl, Tsimshian, and Chinook.

|

|

|

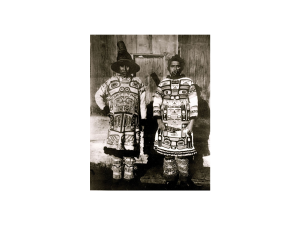

| Seattle Seahawks Helmet | Chilkat Chiefs. (1895). Coudahwot and Yehlh-gouhu, Chiefs of the Con-nuh-ta-di | Chief’s Seat. (1972). Ksan Historical Village |

Style, Convention, and Culture

In 1791, French ship Captain Etienne Marchand recorded observations of the inhabitants of Canada’s Northwest Coast. He comments on ship’s Surgeon Roblet’s puzzled reflection on the region’s art:

[The designs] “at first appeared to me to resemble nothing, I distinguished … a human figure which its extraordinary proportions, still more than its size, render monstrous. Its thighs extended horizontally, … out of all proportion.” … It might be imagined that [this art] somewhat resembles those shapeless essays of an intelligent child, who undertakes, without principles, to draw objects. …

I remark however that voyagers [to] … the Northwest Coast of America saw works … in which proportions were tolerably well observed and the execution of which bespoke a taste and perfection which we do not expect … in countries where men seem to have the appearances of savages (Holm, 215, p. 6).

Commenting on this description from two centuries later, Holm acknowledges “its lack of sympathy with the natives” and an “ethnocentric orientation” (p. 7). Only in the last century has the Euro-American perspective begun to overcome its patronizing dismissal of “primitive” cultures.

But let’s consider the aesthetic dimension of this clash of cultural perspectives. Seeing with 18th Century eyes, Roblet thinks of children’s drawing, particularly the absence of “principles” of technique. But which principles? As a cultured Frenchman, Roblet simply assumes that Neo-Classical European conventions are universally applicable, superior standards of artistic excellence:

It’s easy to recognize the source of Roblet’s difficulty. For him, the images fail at the conventional expectation he assumes to be universal: good art represents visual subjects with precise modeling, proportions, and perspective. He thinks he sees faces and limbs, but these are oddly proportioned. Worse, some aspects of the designs appear to “resemble nothing.” To one steeped in the Renaissance tradition, these designs make no sense.

Marchand is not so sure. Perceiving that this art follows its own rules, he dimly senses the context gap between his European eyes and the designs’ Context of Origin. In particular, the issue here is a clash between two kinds of representation:

Representational Art: visual art which seeks to imitate the look of a subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art.

Mimesis:[1] a representational technique in visual art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

Stylized Art: art that represents the idea of a visual subject through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis

Many viewers today are comfortable enough with that Seattle Seahawks logo. Our audience context has familiarized us with strongly stylized art in advertisements, cartoons, and contemporary design. Pacific Northwest Coast art is stylized according to very strict rules. If we want to be more than merely comfortable with it, we need to explore its rules in context.

[1] Mimesis: from a mainstream perspective in Europe in the Americas, mimetic realism appears to be “natural,” intrinsic to human perception. However, as we shall see, it has a clear cultural lineage descended from the work of classical Greek artists. It is itself conventional, culturally determined, learned and by no means universally human.

The Formline Style

Artists of the Northwest coast have for centuries composed magnificent designs within a strict pattern of Conventional rules. In 1965[2], Bill Holm analyzed the rules of that style from a Western academic perspective. Note the subtitle: Northwest Coast Indian Art: an Analysis of Form. Holm focuses, not on the symbolic significations of mythic and totemic figures, but on the rules and patterns of their style:

Pacific Northwest Coast art features a roster of animals—ravens, eagles, orcas, bears, badgers—and human faces. But these figures are fractured, with body parts—eyes, ears, joints, feathers—distorted and isolated within abstract design features (Holm p. 11). The “formal element of the designs … takes on such importance as to overshadow” the figure which “becomes very obscure” (p. 9).

Holm’s formal analysis recognizes that stylistic conventions govern the selection and location of body part within a formline design. The term refers to a visual unit fusing two formal components of visual art:

Line: a two-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth

Form: a three-dimensional shape or object with height, width, and depth

[2] 1965: the most recent edition of Holm’s masterful analysis, cited in these pages, is dated 2016.

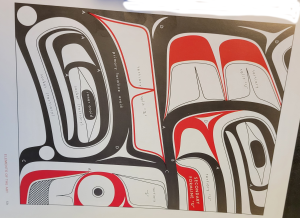

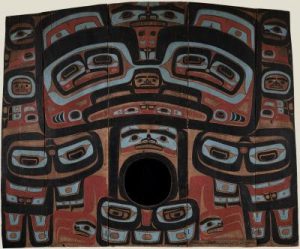

Formlines of varying thickness use strictly coded colors to organize the components of the design. Heavy, black formlines dominate the composition so remarkably that Holm refers to them as the primary element. Red is used for form lines defining secondary elements within the whole, e.g. cheeks, tongues, and limbs (Holm, p. 30). Blues and greens are used for tertiary elements such as eye sockets, feathers, or fins (p. 32).

The stylized spaces delineated by these formlines enclose roughly geometrical shapes. Holm uses the term ovoid for the distinctive, rounded rectangles that form stylized eyelids and U forms which may be split or doubled. These forms, simple but capable of endless variation, comprise the vocabulary of formline art. Animal figures can be composed intact, split or rearranged, or distributed into various sections of the design (Holm, p. 12). Far from being a primitive or savage tradition, formline art is both elaborately regulated and flexible enough to support rich variations among separate peoples and individual artists. Holm’s generic diagram establishes the core formal vocabulary from which these variations are derived.

|

| Bill Holm. (2015, p. 59) Diagram of formline conventions. |

The flexibility of these forms have supported a wide variety of applications. The formline style graces “boxes, settees, house fronts, interior partitions and screens, canoes, dishes, spoons, rattles” (Holm, p. 14).

|

|

|

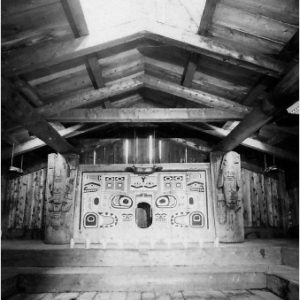

| Richard Carpenter. (c 1860). Bent Corner Chest. | Haida people. (c 1850). Chilkat Tunic | Chief Shake’s Interior House. (1966). |

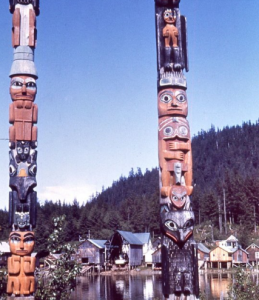

The most famous application of formline design, the totem pole, plays roles in many of these functions. A Totem is a sacred symbol or spirit animal that invokes a ritual or religious tradition and may be associated with a family, clan, or tribe. The crest function[3] of totemic house posts can affirm clan identity.

|

|

|

| Totems on Chief Shake’s Island. (1960). | Dlam (Interior Housepost) (c 1907). Left post. | Chief Mungo Martin (1953). Kwakwaka’wakw “big house” |

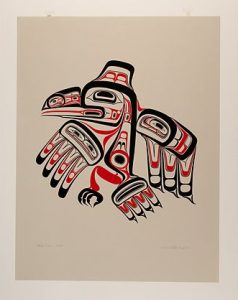

Today, talented artists keep the formline tradition alive. Iljuwas Bill Reid, of maternal Haida descent, immersed himself in Haida tradition and sculpted, drew, and painted compositions that extended the possibilities of formline art:

|

|

|

| Haida Raven (1972). Ink on paper. | Cedar Screen. (1968). Laminated red cedar. | The Raven and the First Men. (1978). Laminated cedar beams. |

[3] Crest function: a heraldic use of an image to signify clan or family identity

Raven Brings Light

The traditional arts of the Indians of the Northwest Coast are indissolubly linked to legends and myths. No other art has broken through the barrier between the natural and the supernatural worlds with such momentum.

–Claude Levi-Strauss, Preface to Reid and Bringhurst, (1996) The Raven Steals the Light

So, Pacific Northwest Coast art features a specific roster of animals, especially ravens, eagles, orcas, bears, badgers. You are surely wondering, why these animals? There must be some stories there, right?

Holm subtitled his book A Formal Analysis. When he wrote the first edition in 1965, inquiries into the peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast had been dominated by anthropologists such as Franz Boas and Claude Levi-Strauss. Scholarship had meticulously studied clan structures, rituals, technologies, and social norms. Where possible, these studies draw deeply on folklore. In 1909, John R. Swanton recorded narrations in English of Tlingit story tellers. These oral narratives are authentic, but not necessarily authoritative. Remember that every telling of an oral narrative is a performance which differs and evolves from earlier versions.

For many Native American peoples, animal species are represented by spiritual avatars who play key roles in origin stories and moral fables. A trickster god with multi-layered personality, Raven deceives, sometimes playfully, spirit beings and humans, teaching morals and conveying boons and blessings.

from The Raven Steals the Light

Raven was first called Kit-ka’ositiyi-qâ-yît (“Son of Kit-ka’ositiyi-qâ”). When his son was born, Kit-ka’ositiyi-qâ tried to instruct him and train him in every way and, after he grew up, told him he would give him strength to make a world. … Then there was no light in this world, but it was told him that far up the Nass [River] was a large house in which someone kept light just for himself.

Raven thought over all kinds of plans for getting this light into the world and finally he hit on a good one. The rich man living there had a daughter, and he thought, “I will make myself very small and drop into the water in the form of a small piece of dirt.” The girl swallowed this dirt and became pregnant.

When her time was completed, they made a hole for her. … Round bundles of varying shapes and sizes hung about on the walls of the house. When the child became a little larger it crawled around back of the people weeping continually, and as it cried it pointed to the bundles. … Its grandfather said, “Give my grandchild what he is crying for. Give him that one hanging on the end. That is the bag of stars.” So the child played with this, rolling it about on the floor back of the people, until suddenly he let it go up through the smoke hole. It went straight up into the sky and the stars scattered out of it, arranging themselves as you now see them. …

Sometime after this he began crying again, and he cried so much that it was thought he would die. Then his grandfather said, “Untie the next one and give it to him.” He played and played with it around behind his mother. After a while he let that go up through the smoke hole also, and there was the big moon.

Now just one thing more remained, the box that held the daylight, and he cried for that. His eyes turned around and showed different colors, and the people began thinking that he must be something other than an ordinary baby. But it always happens that a grandfather loves his grandchild just as he does his own daughter, so the grandfather said, “Untie the last thing and give it to him.” His grandfather felt very sad when he gave this to him. When the child had this in his hands, he uttered the raven cry, “Gâ,” and flew out with it through the smoke hole. Then the person from whom he had stolen it said, “That old manuring raven has gotten all of my things.” …

Then Raven, … walked down along the bank of Nass river until he heard the people … as they fished along the shore in the darkness. … They had already heard that Nâs-cA’kî-yêl had something called “daylight,” which would someday come into the world, and … they were afraid of it.

Then Raven shouted to the fishermen, “Why do you make so much noise? If you make so much noise I will break daylight on you.” Eight canoe loads of people were fishing there. But they answered, “You are not Nâs-cA’kî-yêl. How can you have the daylight?” … Then Raven opened the box a little and light shot over the world like lightning. … He opened the box and there was daylight everywhere. …

Raven showed the Tlingit what to do for a living. … At that time the world was full of dangerous animals and fish. … Raven told the people that some animals were to be their friends (their crest animals[4]) to which they were to talk. … Raven taught the people how to make halibut hooks and went out fishing with them. … He showed them how to make a canoe. … At first the people were afraid to get into it, but he said, “The canoe is not dangerous. People will seldom get drowned” (Swanton, 1909, p. 84).

[4] Crest animals: i.e. heraldic animals displayed on poles, canoes, and structures of houses to indicate one’s clan

The tale of Raven bringing light serves one of the key roles of myth:

In traditional societies, folklore and myth explain why things are as they are, arrange them into meaningful categories, and instruct members of the culture on how to hunt, fish, cultivate crops, and fashion clothing, utensils, and shelter. Moral tales guide proper behavior and connect with reassuring visions of the afterlife.

Vital Questions

We normally think of myth as the domain of storytelling. Yet, as we have seen in Egyptian, Hindu, and Pacific Northwest Coast art, myth expresses itself in interwoven visual and narrative forms.

Context

We have barely scratched the surface of the context that produced Pacific Northwest Coast art and narrative. These mythic structures express and facilitate a complex social structure divided into clans and governed by rituals and mating conventions. If you are interested, there is a wide literature on these matters.

Content

We have noted that Formline art contains two primary contents:

- Totem animals reflecting Haida, Tlingit, and other Northwest Coast cultures

- Abstract forms that organize and blend with body parts of these animals

Form

From an artistic point of view, formline art is noteworthy for the precedence of form and style over representation. Visual subjects are recognizable, but fragmented and subordinated beneath the elegant lines and forms of the style, boldly drawn in primary colors and shaped by a fusion of geometrical linearity and organic curves. Style. Form. Composition. Let’s remember these concepts as we go forward.

References

Carpenter, Cptn. R. (Du’klwayella). (c 1860.) Bent-corner chest. Macapia, P. Photograph. Seattle WA: Seattle Art Museum. https://art.seattleartmuseum.org/objects/13026/bentcorner-chest?ctx=9585e0cd-2933-4849-b557-523370f15312&idx=7

Chief Mungo Martin (1953). Kwakwaka’wakw “big house” with heraldic pole. Thunderbird Park in Victoria, British Columbia. Bushby, R. (2007). Photograph. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wawadit%27la(Mungo_Martin_House)_a_Kwakwaka%27wakw_big_house.jpg

Chief Shakes Interior House. (1966). Wrangell, AK. de Menil, A. Photograph. Vancouver, B. C.: Simon Fraser University.. Bill Reid Centre. https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/billreid-3788/chief-shakes-interior-house

Chief’s Seat. (1972). Ksan Historical Village. Vancouver, B. C.: Simon Fraser University. George and Joanne MacDonald Northwest Coast Image Archive https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/billreid-1354/chiefs-seat

Chilkat Chiefs [Photograph]. (1895). Coudahwot and Yehlh-gouhu, Chiefs of the Con-nuh-ta-di (Ganaxtedi). Vancouver, B. C.: Simon Fraser University. George and Joanne MacDonald Northwest Coast Image Archive https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/billreid-4188/chilkat-chiefs

Dlam (Interior Houseposts). (c 1907). Cole, S. Photograph. Seattle WA: Seattle Art Museum. https://art.seattleartmuseum.org/objects/4292/dlam-interior-housepost?ctx=9585e0cd-2933-4849-b557-523370f15312&idx=13

Haida people. (c 1800-1850). Chilkat tunic. UBC Museum of Archeology. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.12729504

Holm, B. (2015). Northwest Coast Indian Art: an Analysis of Form. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

McMaster, G. (2020). Iljuwas Bill Reid. Art Canada Institute. https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/iljuwas-bill-reid/

Mortuary Memorial Poles (1901). Haida People. SGang Gwaay Village Site. Photographer Newcombe, C. F. Vancouver, B. C.: Simon Fraser University. George and Joanne MacDonald Northwest Coast Image Archive https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/billreid-5091/sgang-gwaay-village-site

Mother eagle house post (1966). de Menil, A. Photograph. Vancouver, B. C.: Simon Fraser University.. Bill Reid Centre. https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/billreid-3659/house-post

Peterson, A. (2007). Naming ceremony chest. Seattle, WA: Seattle Art Museum. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14725870

Raven gate post. (1960). de Menil, A. Photograph. Vancouver, B. C.: Simon Fraser University.. Bill Reid Centre. https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/billreid-3226/raven-gate-post

Reid, B. (1968). Cedar Screen (Sculpture). Victoria, CA: Royal B.C. Museum. In McMaster, Ed. (2020). http://collection-online.moa.ubc.ca/search/item?keywords=Bill+Reid+Raven&row=42

Reid, B. (1972). Haida Raven [Print]. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology. Object number A17113 http://collection-online.moa.ubc.ca/search/item?keywords=Bill+Reid+Raven&row=39

Reid, B. (1977). Children of the Raven [Serigraph]. Vancouver, Canada: SFU Bill Reid. In McMaster, Ed. (2020).

Reid, B. (1978).The Raven and the First Men [Sculpture]. Vancouver, CA: University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology. Wikimedia https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e0/The_Raven_and_the_First_Men%2C_Museum_of_Anthropology_%287960613690%29.jpg

Reid, B. and Swanton, J. R. (1996). The Raven Steals the Light. Seattle, WA: Washington University Press.

Seattle Seahawks Logo [Clipart] (N.D.). Logos Discovery Engine https://www.logolynx.com/topic/seahawks+helmet

Swanton, J. R. (1909). Tlingit Myths and Texts. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 39. Sacred Texts https://www.sacred-texts.com/nam/nw/tmt/index.htm

Tlingit people. (late 1800s). Naaxein (ceremonial blanket). Seattle WA: Seattle Art Museum https://art.seattleartmuseum.org/objects/13497/naaxein?ctx=50ad951d-1ae1-44e3-b068-069f5b966f10&idx=25

Totems on Chief Shakes Island. (1960). Schallerer’s Photo Shop, Photograph. Vancouver, B. C.: Simon Fraser University.. Bill Reid Centre https://digital.lib.sfu.ca/billreid-3252/totems-chief-shakes-island

Who was Bill Reid? [Article]. (N.D.). Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art [website]. https://www.billreidgallery.ca/pages/about-bill-reid

Yéil X’eenh (Raven Screen) [Painting]. (c 1810). Macapia, P. Photograph. Seattle WA: Seattle Art Museum. https://art.seattleartmuseum.org/objects/6555/yeil-xeenh-raven-screen?ctx=fab0ecdc-231f-4746-a39c-cdef6cf8703b&idx=43

art that represents the idea of a visual subject through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis. Exam-ples: animation, cartoons, caricatures, traditional figures in many cultures

the social, cultural, and historical milieu which influence artists’ contents, compositions and themes positively and/or negatively

the social, cultural, and historical perspective from which audiences respond to works of art, often clashing with the context of origin and requiring a bridge to close the gap

an aspect of art which is expected and understood by the audience in a particular tradition