Appendix: Formal Elements of Art

All visual art—representational, mimetic, styled, or abstract—is comprised of Formal components. Representational Art uses line, form, and color to depict visual subjects. Abstract art makes no effort to represent a visual subject, but it employs the same formal elements. Indeed, in the absence of a represented subject, our attention with an abstract is forced to consider line, color, and composition in themselves.

We are always affected by form. We may say, “Oh, what bright colors in that painting!” Yet it is often necessary for a viewer to pay particular attention to form in order to really “get” a composition. If you would like to strengthen your understanding of core formal elements of art, please explore this Appendix.

As we begin, let’s be very clear. We are looking here at sheer form and composition, not at visual subjects or themes. This Appendix is not about “What is it?” or “What does it mean?” It is about sheer form, not content.

Line, Shape, Form

Primary Visual Elements

Line: a one-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth.

Shape: a two-dimensional figure displaying only height and width

Form: a three-dimensional shape or object with height, width, and depth

A line can be straight or curved. Ansel Adams’ image of the Tetons is dominated by the sinuous, curving line of the Snake River:

|

|

|

| Ansel Adams. (1942). The Tetons and the Snake River. Gelatin silver print. | Mosaic of the Donors: Emperor Justinian. (547). | Leonardo da Vinci. (1503-1506). Mona Lisa. Oil on panel. |

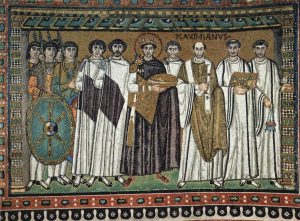

Contour Lines define visual elements. They can be directly drawn, as in the Mosaic of the Donors. Notice how firmly drawn lines delineate contours of fabric and figure. On the other hand, contour lines can be suggested by contrast between colors or textures. The Impressionists used to say “There are no contour outlines in nature!” Leonardo’s Sfumato technique blurs the contour line with subtle brushwork.

A distinction is often drawn between two orders of Form:

Organic Form: irregular shapes or forms with the unpredictable, often curving lines and contours of the natural world: rocks, clouds, tree trunks, an animal’s skin

Geometric Form: precisely defined lines and arcs defined by human artifice, e.g. spheres, cones, triangles, rectangles, flat, polished surface

Geometric forms are generally associated with human artificiality or industry. Organic forms suggest uneven contours of most natural objects. Can you distinguish the organic and geometric forms in Kandinski’s semi-abstract canvas?

|

| Wassily Kandinsky. (1925). Yellow, Red, Blue. Oil on canvas. |

Color, Light and Texture

In a limited space, we can’t begin to do justice to color, but we need to consider it. Color is frequently divided into three components: Hue, Saturation, and Value. Hue refers to a specific color arising from wavelengths on the spectrum of light.

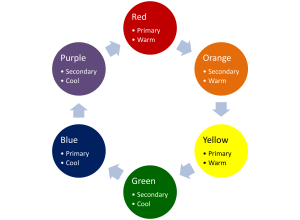

Color Relationships in the Color Wheel

Primary colors: hues that emerge without being mixed with others–Red, Yellow, Blue

Secondary colors: hues formed by mixing other hues—e.g. red + yellow = orange

Analogous Colors: closely related hues that share color components and mix harmoniously when placed against each other in a composition

Complementary colors: Hues on opposite sides of the color wheel that enhance each other through maximum contrast, green with red, yellow with purple, orange with blue.

Color Temperature: the quality of warmth or chill imparted by pure color, red, orange, and yellow (warm) versus green, blue, and purple (cool)

Color temperature can be a matter of association—blue and the Blues—or of culture. In Asian cultures, white is often associated with death. The impact of a given hue is also affected by two closely related factors.

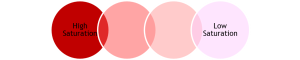

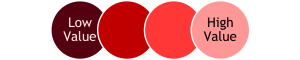

Color Saturation and Value

Saturation: a color’s brightness or dullness due to the intensity of the pigment

Value (or Tone): the degree of lightness or darkness of a composition’s colors or texture

|

|

Notice the difference here. Saturation merely measures the intensity of pigment. The Value scale stretches from light to dark. At one extreme, white reflects all wavelengths of the light spectrum; black, at the other end, reflects none. Value, which can be achieved by elements other than color, affects the mood of a composition and its elements.

Texture

Texture: surface quality, how the actual surface of the medium feels or would feel

Simulated texture: illusions of texture consciously created by artists, e.g. fabrics and drapery

Actual texture: tangible textures of medium or technique, e.g. mosaic tiles, marble, canvas, paint, and brushstrokes

Some painters work hard at erasing all evidence of their materials and technique. Others Foreground or draw our attention to these dimensions of their work. A painter may intentionally highlight the texture of paint in a strong brushstroke or the weave of the canvas. In Impasto, thickly textured daubs of paint are applied with a palette knife. Modern painters often add actual textures to the paint: sand, bits of string, paper cutouts, sticks.

Space and Movement

Visual compositions are composed of Line, Shape, and Form. When assembled, they form spatial relationships:

Positive Space: the space in a visual Composition taken up by forms and subjects

Negative Space: the open space in a visual Composition surrounding forms and subjects

Picture Pane: the 2-dimensional visual space that comprises the surface of a painting, photograph, or mosaic.

Virtual Space: in some paintings, the illusion of depth created through Linear Perspective and Foreshortening

Sightlines: in visual art, arrangements of elements that lead the viewer’s eyes in a controlled direction. Often suggested by the Eyelines of figures in the composition

We have already explored techniques by which 2-dimensional paintings project the illusion of three-dimensional space. But what of time in a stationary painting or sculpture? Consider the Suggested Movement in Marcel Duchamp’s image—images?—of a descent down stairs.

|

| Marcel Duchamp. (1912). Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2. Oil on canvas |

Even in static images, viewers’ eyes are always moving. How does Mengs steer your eyes in his vision of Parnassus, the traditional home of the arts in Greek myth? Do you start with the central figure, the God Apollo? Do you then circle around the spiraling figures of the muses? Raphael’s similarly controls guides our eyes in a circle, this time following the Holy Family’s lines of sight.

|

|

| Anton Raphael Mengs. (c 1760). Parnassus. Oil on panel |

Raphael da Urbino. (1506). Canigiani Holy Family. Oil on canvas |

Design Principles: Composition

Composition

Visual Composition

Color Schemes

Approaching a canvas, a painter will choose particular hues and prepare wet lumps of paint on a flat board known as a palette. Colors will be chosen to interact with each other and create a desired aesthetic whole—an early stage of Composition:

Color Palette: the range of colors selected to compose a painting’s design

Monochromatic palette: a color palette with a noticeably narrow range of Hue and Value

Polychromatic palette: a color palette with a noticeably wide range of Hue and Value

|

|

|

| Raphael da Urbino. (1507). Holy Family with the Lamb. Oil on panel. |

Georges Braque. (1911). Man with a Guitar. Oil on canvas. |

Vincent van Gogh. (1888). The Sower. Oil on canvas |

Integrating Principles

In his remarks on Leonardo’s The Last Supper (1498), Gombrich penetrates to the relational essence of Composition: resonant interplays between elements within an integrated whole. While the topic is vast, we can mention a few core relational effects:

- Unity: the degree to which elements in a work of art come together in an integrated whole.

- Harmony: a correspondence between unlike elements that contributes to overall unity

- Rhythm: an artistic effect generally achieved by repetition of forms. In visual art, a sense of movement arising from repeated elements in the composition

One way to achieve unity in a visual work is through Rhythm. As we’ve seen in our discussion of Figures of Scheme, rhythm arises from patterns of repetition. In visual art, rhythm arises from repeated or parallel elements in the composition.

|

|

| Meindert Hobbema. (1689). The Avenue at Middelharnis. Oil on canvas. |

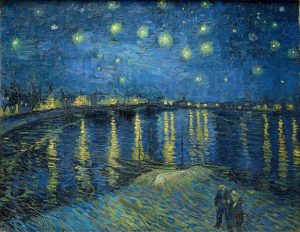

Vincent van Gogh. (1888). Nuit Étoilée sur le Rhône (Starry Night over the Rhone). Oil on canvas |

The rhythmic, formal repetition of Hobbema’s row of poplar trees pulls our eyes up along the road. van Gogh rhythmically aligns starbursts with parallel lines of light projecting on dark waters.

Unity and Harmony obviously make use of similarity. But they also work through contrast. After all, van Gogh gains rhythmic harmony from the juxtaposition of distant stars with light on water. Consider the harmony that emerges from Ghirlandaio’s contrast between the homeliness of age and the beauty of youth, a contrast bridged by the love shared by the figures.

|

|

| Domenico Ghirlandaio, D. (c 1490). Portrait of an Old Man and a Young Boy. Oil on canvas. | Piero dela Francesca. (c.1455-60). Flagellation of Christ. Oil on canvas. |

Some artists challenge Unity with diversity. Piero stitches three distinct subjects together, the flagellation scene, an architectural study, and a view of two gentlemen talking on the street.

Organizing Space

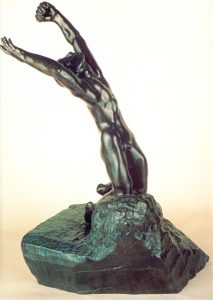

Above all, visual Composition organizes space. Some compositions strive to open out into Negative Space. Rodin’s figure of the prodigal son[1] pierces space with a rising, curving verticality.

[1] Prodigal Son (Luke 15.11-32): in Jesus’ parable of redemption, a wayward youth, having abandoned his home and wasted his money, repents and returns to a father who receives him with grace and joy.

|

|

| Auguste Rodin. (1889). The Prodigal Son. | Henry Moore. (1963). Reclining Mother and Child. |

By contrast, Moore’s semi-abstract meditation on motherhood encloses a rectangular negative space of maternal nurture within a powerful Organic Form holding off the menacing expanse of the outside world.

Spatial Zones

Foreground: in 3-dimensional space, the nearer zone of vision, often a Positive Space containing figures of primary interest

Middle Ground (or middle distance): in 3-dimensional space, a moderately distant visual zone in which figures are partially visible

Background: in 3-dimensional space, the deep distance comprised of minimally visible figures and open, Negative Space

Painters expressively compose figures, objects, and space. Thomas Cole draws the viewer’s eye from the base of a bent tree in the Foreground, past a Middle Distance and out into the vast Negative Space of the sky.

|

|

| Thomas Cole. (1836). The Oxbow. Oil on canvas. | Leonardo da Vinci. (1485). The Virgin of the Rocks. Oil on panel. |

By contrast, Leonardo encloses his figures in a cramped, sinister space filled with claustrophobically intrusive rocks.

Landscape painters face a compositional question: where shall they place the horizon? The three landscapes below range from low to high horizons. Raising or lowering the horizon dramatically shifts the balance between positive and negative space.

|

|

|

| John Constable. (1813). View Towards The Rectory From East Bergholt House. Oil on canvas. | Jean Baptiste Raguenet. (1763). A View of Paris from the Pont Neuf. Oil on canvas. | Vincent van Gogh. (1888). The Sower. Oil on canvas. |

Compositional Line and Form

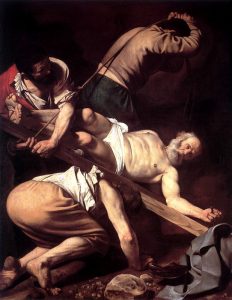

Powerful, implicit, lines and forms emerge as we notice the arrangements of elements in the Picture Pane. In two compositions of the Holy Family, Raphael illustrates distinctive design forms: the solidly grounded triangle and the diagonal line. Caravaggio aptly composes the Crucifixion of St. Peter[1] in a right angle suggesting an inverted cross.

|

|

|

| Raphael da Urbino. (1506). Canigiani Holy Family. Oil on canvas. | Raphael da Urbino. (1507). Holy Family with the Lamb. Oil on canvas. | Caravaggio. (1600). The Crucifixion of St. Peter. Oil on canvas. |

[1] Crucifixion of St. Peter: according to legend, when the Apostle Peter was condemned to death, he insisted on being crucified upside down because he didn’t feel worthy of enduring the same fate that his Lord Jesus suffered.

Always pay attention to the design scheme that composes visual elements. Look for spirals, angles, and lines: vertical, horizontal, or diagonal.

Balance

Compositional Balance

Balance: in visual art, the distribution of visual weight or placement of elements

Symmetrical balance: an equilibrium achieved by aligning like elements in a visual field on both sides of an implied central vertical or horizontal axis

Radial balance: an equilibrium achieved by arranging elements in a visual field so they seem to radiate around a central element

Asymmetrical balance: an equilibrium achieved between unequal elements in a visual field or along off center vertical or horizontal axes

|

|

| Meindert Hobbema. (1689). The Avenue at Middelharnis. Oil on canvas. |

Anton Raphael Mengs. (c 1760). Parnassus. Oil on panel. |

Hobbema’s landscape achieves Symmetrical Balance by dividing roughly equal spaces with a central vertical axis–the lines of trees. Mengs achieves Radial Balance by opposing circles of Muses.

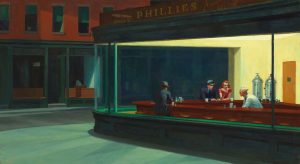

Composition becomes really interesting when it balances off center and asymmetrical elements. Tōhaku balances Positive Space, the clumps of trees, with Negative Space, the open zones of mist. Notice, too, that the weighting of right and left panels is imbalanced. Hopper similarly balances light and drama across the right and center with a smaller but menacing zone of dark mystery to the left.

|

|

| Hasegawa Tōhaku. (16th C). Pine Trees. Ink wash on paper. | Hopper, E. (1942). Nighthawks. Oil on canvas. |

A superb way to improve your capacity for “getting” art is to begin to focus on composition. What are the compositional elements in the work? How are they arranged? What does the composition do to your eyes? How do the elements compare? Find balance? Composition opens new dimensions of appreciation for representational art and can help you begin to grasp what abstract artists are doing.

Sources

Adams, A. (1942). The Tetons and the Snake River [Photograph]. The Ansel Adams Gallery https://www.anseladams.com/products/explore-tetons-and-the-snake-river

Braque, G. (1911). Man with a Guitar [Painting]. New York City, NY: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79048?artist_id=744&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

Caravaggio. (1600). The Crucifixion of St. Peter. [Painting]. Rome, Italy: Basilica Parrocchiale Santa Maria del Popolo. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caravaggio-Crucifixion_of_Peter.jpg

Caravaggio. (c 1607). Flagellation of Christ [Painting]. Naples, Italy: National Museum of Capodimonte. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caravaggio/flagellation-of-christ

Claude, L. (1642). Cleopatra Disembarking at Tarsus [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée du Louvre. INV 4716; MR 1738. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010061018

Claude, L. (1646). L’embarquement d’Ulysse (Embarkation of Ulysses) [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée du Louvre. INV 4719; MR 1748. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010061027

Cole, T. (1836). View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow [Painting]. New York City, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 08.228 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10497

Constable, J. (1813). View towards the Rectory from East Bergholt House [Painting]. Private Collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/john-constable/view-towards-the-rectory-from-east-bergholt-house-1813

Constable, J. (1823). View of Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds [Painting]. London, UK: Victoria and Albert Museum. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O56227/salisbury-cathedral-from-the-bishops-oil-painting-constable-john-ra/

Duchamp, M. (1912). Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2 [Painting]. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/marcel-duchamp/nude-descending-a-staircase-no-2-1912

Francesca, Piero della. (c.1455-60). Flagellation of Christ [Painting]. Urbino, Italy: Palazzo Ducale. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/piero-della-francesca/the-flagellation-of-christ-1450-1

Ghirlandaio, D. (c 1490). Portrait of an Old Man and a Young Boy [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. RF 266. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010064987

Hobbema, M. (1689). The Avenue at Middelharnis [Painting]. London, UK: National Gallery. NG830. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/meindert-hobbema-the-avenue-at-middelharnis

Hopper, E. (1942). Nighthawks [Painting]. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago. 1942.51 https://www.artic.edu/artworks/111628/nighthawks

Kandinsky, V. (1925). Yellow-Red-Blue [Painting]. Paris, FR: Georges Pompidou Center. AM 1976-856. https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/ressources/oeuvre/cEpEKE

Leonardo da Vinci. (1495). The Last Supper [Painting]. Milan, IT: Santa Maria delle Grazie. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/leonardo-da-vinci/the-last-supper-1495

Leonardo da Vinci. (1503-1506). Mona Lisa [Painting]. Paris: Musee du Louvre. INV 779; MR 316 https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010062370

Leonardo da Vinci. (about 1508). The Virgin of the Rocks [Painting]. Paris: Musée du Louvre. INV 777. https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/virgin-rocks

Malevich, K. (1916). Suprematist Composition [Painting]. Tula, Russia: Tula Regional Museum of Fine Arts. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/kazimir-malevich/suprematist-composition-1915

Mengs, A. R. (c 1760). Parnassus [Painting]. St. Petersburg, Russia: The Hermitage Museum. ГЭ-1327. https://www.hermitagemuseum.org/wps/portal/hermitage/digital-collection/01.+Paintings/38284/

Mondrian, P. (1932). Composition No 10 [Painting]. Private Collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/piet-mondrian/composition-no-10-1942

Mosaic of the Donors: Justinian and his Court [Mosaic]. Ravenna, Italy: Basilica di San Vitale. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/byzantine-mosaics/emperor-iustinianus-and-his-suite-547

Raguenet, J, B.. (1763). A View of Paris from the Pont Neuf. Oil on canvas. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Museum, ID 71.PA.26. Retrieved from http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/581/jean-baptiste-raguenet-a-view-of-paris-from-the-pont-neuf-french-1763/

Raphael da Urbino. (1506). Canigiani Holy Family. [Painting]. Munich, Germany: Alte Pinakothek. https://www.pinakothek.de/en/exhibition/raffael-1520-2020

Raphael da Urbino. (1507). Holy Family with the Lamb [Painting]. Barcelona, Spain: Museo del Prado. https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-holy-family-with-a-lamb/828f13e3-5a4e-4107-b0a4-5607d17dfd66

Rodin, A. (1889). The Prodigal Son [Sculpture]. Paris, France: Musée Rodin. https://www.musee-rodin.fr/en/musee/collections/oeuvres/prodigal-son

Taylor, J. C. (1981). Learning to Look: a Handbook for the Visual Arts. 2nd edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tōhaku, H. (16th Century). Pine Trees [Painting]. Tokyo, Japan: Tokyo National Museum. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hasegawa_Tohaku_-_Pine_Trees_(Sh%C5%8Drin-zu_by%C5%8Dbu)_-_right_hand_screen.jpg

van Gogh, V. (1888). The Sower (Sower with Setting Sun) [Painting]. Otterlo, NL: Kröller-Müller Museum. https://krollermuller.nl/en/vincent-van-gogh-the-sower

van Gogh, V. (1888). La Nuit étoilée (The Starry Night over the Rhone) [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/la-nuit-etoilee-78696

in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any subject or signification: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement

visual art which seeks to imitate the look of a subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

visual art that makes little or no effort to represent any recognizable subject and appeals to purely aesthetic sensibilities

the boundary line that defines a shape or form in a visual composition. A contour line can be directly drawn or achieved merely through contrast be-tween the colors of the subject and the background.

a technique of representation that seeks to capture, not the “real thing,” but rather one’s subjective experience of the subject

in painting, a subtle form of brushwork that blends tones, colors, and forms so that they seem to melt into each other. Leonardo characterized his technique as one “without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke.”

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

a specific color, often achieved by mixing primary colors in paint or in the colored elements of a mosaic

a color’s brightness or dullness due to the intensity of the pigment

the degree of lightness or darkness of a composition’s colors or texture

the application of oil paint, often with a palette knife, to produce thickly textured masses of color

in visual art, a 2-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth. Line may be straight or curved, directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

in visual art, a two-dimensional figure with a more or less defined border displaying only height and width

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

an illusion of depth created by contrasting the sizes of objects on the basis of how near or far they are from the eye of the viewer. E.g. a human figure in the foreground will be larger than a tall building in the distance.

an implied line defined by the direction stretching from the gaze of a figure in the scene

the suggestion of movement in the frame based on the viewer’s knowledge. E.g. a viewer looking at a painting of a car chase will expect the cars to be moving

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc

an artistic effect generally achieved by repetition of forms. In figurative language, patterns of Scheme which repeat sounds or ideas. In poetry, patterns that arise from repeated elements such as rhyme and meter. In visual art, a sense of movement arising from repeated elements in the composition

repeated patterns of expression that enhance the rhetorical effect of the text: e.g. alliteration, anaphora, catalogue, parallelism

the degree to which elements in a work of art come together in an integrated whole

a correspondence between unlike elements that contributes to overall unity

a sector of a visual composition that seems empty, devoid of clearly defined and weighted visual subjects

in visual art, an irregular form such as a cloud or rocky terrain that suggests natural origin distinct from human artifice

in 3-dimensional space, the nearer zone of vision, often a Positive Space containing figures of primary interest

(or Middle Ground): in 3-dimensional space, a moderately distant visual zone in which figures are partially visible

the virtual window glass through which the 2-dimensional surface of a painting’s Medium—fresco, canvas, panel—"looks out” into a projected space

in visual art, an equilibrium achieved by aligning elements of similar weight and scale in a visual field on both sides of an implied central vertical or horizontal axis

in visual composition, an equilibrium achieved by arranging elements in a visual field so they seem to radiate around a central element

a sector of a visual composition that is filled with the weight and substance of elements of color, line, or form