9.5 American Romanticism

The movement of High Romanticism is associated primarily with Europe, especially Germany and England. As Friedrich, Blake, and Wordsworth were formulating their visions, the brand-new nation of the United States was attempting to develop its own cultural identity. What do you think? Would America be inspired more by Neo-Classicism or by Romanticism?

It’s a complex question, of course. But imagine yourself setting out into an apparent wilderness[1] to wrench farms out of the dirt and forge buildings and towns from sheer hard work. Where did you find guidance and wisdom? From ancient lore or from your own judgement?

[1] An apparent wilderness: the concept of wilderness is dependent on one’s cultural orientation. What appeared as wilderness to a European frame of reference appeared very differently to indigenous peoples who had made homes there for thousands of years.

Romanticism translated very well to the new nation of America. The early 19th Century educator and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson embraced a transcendental vision of the human self, as expressed in essays such as “The Oversoul” and “Self-Reliance”:

Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.

Whoso would be a man[1] must be a nonconformist.

Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.

For nonconformity the world whips you with its displeasure.

[1] Whoso would be a man: again, sadly, women are effaced, though Emerson’s ideas apply well to women in a patriarchal society.

If you want to understand the mainstream American perspective on life, you need to have at least a sense of the way Romanticism celebrated and explored the individual. Emerson’s essay lays down the themes of individualism that have driven American society and values to this day.

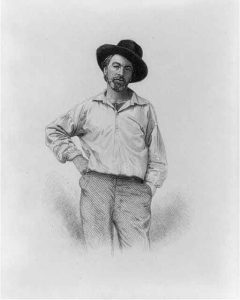

Walt Whitman liberates Verse

|

| Samuel Hollyer. (1854). Engraving of Whitman. |

Walt Whitman was an American poet. That is, he wrote verse that expressed the American spirit in an American voice that could not have arisen anywhere else. As we usually do, let’s read this poem aloud, listening for the rhythms and beat.

Walt Whitman. (1891). “A Noiseless, Patient Spider”

A noiseless patient spider,

I mark’d where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark’d how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form’d, till the ductile[1] anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

[1] Ductile: a property attributed to metals—flexible, pliable, capable of being drawn into thin strands without breaking.

Did you read aloud? If not, try again. Read and listen. Or listen to the audio file above. The poem is highly rhythmic. But its rhythm is different from what we might expect in a poem. Can you hear it?

“A Noiseless Patient Spider” has no Meter. No strict pattern determines numbers of syllables per line or where the stresses fall. Nor do we find any Rhyme or Rhyme Scheme. But by now we know what to do with non-metrical verse, don’t we? Remember how we recognized the poetry in Biblical verse? We listened for oratorical patterns, Figures of Scheme such as Parallelism, Anaphora, and Catalogue.

Whitman’s verse patterns here have an ancient, global heritage. But the tradition of English poetry was deeply committed to Meter and, to a lesser degree, to Rhyme. To this day, many people assume that lines of verse must at least rhyme.

Walt Whitman challenged those assumptions. He composed most of his poetry in what would come to be called Free Verse: poetry that found rhythms that included no Meter or Rhyme. Heavily influenced by Biblical poetry, Whitman’s verse forms emulate the spider he seems patiently forming a fragile web on the rock. He spins out a line, then another, then another, sketching a theme, then repeating it, letting it play out in longer and longer lines, but tying it all together with parallel forms.

So what theme does this liberated verse develop? The poem expresses a reflection on a moment’s observation of nature, a brave but vulnerable spider spinning a web on a rock pounded by the surf, exploring the “vacant vast surrounding” world of ocean. The poet “marks”—i.e. takes notice of—the tireless, repetitive motion of spinning that web “out of itself.”

“Out of itself.” The web reaches out but does so by projecting a filament out of its own body. So stanza two makes the obvious connection: we stand, as does the spider, on the shore of a vast, destructive environment. Something in ourselves, some spirit or soul reaches out into “measureless oceans of space,” seeking a grip that might “catch somewhere,” finding an anchor that might hold us within a safe harbor.

This is pure American Romanticism, the sensitized Soul wandering through Nature, reaching out to form a bond between the “vacant vast surrounding” cosmos and the infinity within. The vision is not religious, but it is deeply Spiritual: a mysterious human inwardness that yearns to transcend life and death and connect with forces of creation.

Whitman’s Song of Myself

The 52 cantos of Song of Myself comprise perhaps Whitman’s most famous poem. Before proceeding, however, let’s pause on that title. Song of Myself? What sort of colossal ego would choose such a narcissistic title and begin “I celebrate myself, and sing myself”?

The answer is, a democratically minded American mind which had adopted the Romantic conception of the self as a standard more authentic than social norms. And this, of course, is how many Americans think today, prioritizing their own viewpoints over “society’s” or over those of “the experts.” Whitman represented the democratic spirit of a nation eager to shrug off the traditions of the old world and follow the banner of rugged individualism.

And it isn’t just egoism. In “Self-Reliance,” Emerson sees the “self” as a spiritual opening onto infinity. Whitman’s self lies within him and within everyone: “For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.” Today, social media venues teem with thousands of voices singing of themselves under the assumption that their thoughts, behaviors and meals are worthy of everyone’s attention on social media.

Walt Whitman. (1892). From Song of Myself

1 I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loaf and invite my soul,

I lean and loaf at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.

My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air,

Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their parents the same,

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death.

Creeds and schools in abeyance,

Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten,

I harbor for good or bad, I permit to speak at every hazard,

Nature without check with original energy. …

52 The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me, he complains of my gab and my loitering.

I too am not a bit tamed, I too am untranslatable,

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

The last scud of day holds back for me,

It flings my likeness after the rest and true as any on the shadow’d wilds,

It coaxes me to the vapor and the dusk.

I depart as air, I shake my white locks at the runaway sun,

I effuse my flesh in eddies, and drift it in lacy jags.

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fiber your blood.

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.

What do you feel when you read these samples from Whitman’s great reflection on life? On the one hand, you may feel put off by the boldly proclaimed assertion of ego. On the other hand, if your cultural orientations have been formed by American values, you may feel entirely comfortable. Many Americans confidently trust and assert themselves, their egos, their instincts.

Don’t tell me what the experts say or what the rules require. I’ll decide what to believe and what to do.

Either way, it’s important to see that Whitman’s Song of Myself emerges from a complex, nuanced conception of Myself. Whitman’s self is a profound inwardness that channels a spiritual core uniting everyone in the world—“For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you”—and all of Nature. Ultimately, Whitman’s Self transcends himself, transcending life and death and connecting with forces of creation.

How do you see your inner self and its relationship to … everyone else and all the world?

Sandberg and the Free Verse Tradition

“Now the most widely practiced verse form in English.” It’s true. English poetry today is dominated by Free Verse. One of the most influential poetic voices to follow Whitman’s lead was Illinois poet Carl Sandberg. His poem “Chicago” celebrates the working class, democratic spirit of a decidedly non-Classical major city.

Carl Sandberg. (1924). Chicago.

Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders:

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them, for I have seen your painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys.

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer: Yes, it is true I have seen the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

And they tell me you are brutal and my reply is: On the faces of women and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger.

And having answered so I turn once more to those who sneer at this my city, and I give them back the sneer and say to them:

Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning.

Flinging magnetic curses amid the toil of piling job on job, here is a tall bold slugger set vivid against the little soft cities;

Fierce as a dog with tongue lapping for action, cunning as a savage pitted against the wilderness,

Bareheaded,

Shoveling,

Wrecking,

Planning,

Building, breaking, rebuilding,

Under the smoke, dust all over his mouth, laughing with white teeth,

Under the terrible burden of destiny laughing as a young man laughs,

Laughing even as an ignorant fighter laughs who has never lost a battle,

Bragging and laughing that under his wrist is the pulse, and under his ribs the heart of the people,

Laughing!

Laughing the stormy, husky, brawling laughter of Youth, half-naked, sweating, proud to be Hog Butcher, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, Player with Railroads and Freight Handler to the Nation.

Sandberg celebrates the virtues of work and working people. But he also insists on a realistic vision that embraces both vices and virtues. Chicago is a great town, Sanders argues, not because it is pure and righteous, but in spite of its corruption, its prostitution, its unpunished gun violence, and the poverty suffered by so many citizens.

Vital Questions

Context

In Europe, High Romanticism was steeped in ancient lore. It honored the human imagination in contact with Nature, but it drew on ancient learning to formulate its Aesthetic.

In America, Romanticism organically fused with the culture of everyday people. The American myth of Rugged Individualism celebrated and empowered the energy and savvy of working class people who pioneered new lands, new technologies, and new forms of industry. “Trust Thyself,” cries Emerson, and Americans have been doing that ever since.

Content

Theoretically, European Romanticism embraced the lives of ordinary people. But the literary ballads of Wordsworth or Tennyson are just that: literary reflections of long-tended poetic gardens. By contrast, Whittman and Sandberg got out there among the people and chronicled actual daily life. Whitman’s Catalogues of professions tour the working lives of a wide range of people, and Sandberg follows that tradition. American Romanticism is more deeply fused with the people than Wordsworth could have imagined.

Form

The obvious Formal strategy to be explored in Whitman and Sandberg is Free Verse. But we should also notice their Diction. Wordsworth called for poetry that used the language actually spoken by people. American Free Verse channeled the voices of the people with distinctive authenticity.

References

Emerson, R. W. (1841). “Self-Reliance.” In Essays, 1st Series. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16643/16643-h/16643-h.htm#SELF-RELIANCE.

Free Verse [Article]. (2015) in Baldick, C. [Ed.]. The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780198715443.001.0001/acref-9780198715443-e-484

Hollyer, Samuel. (1854). Walt Whitman. Steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. Used as frontispiece in 1855 (1st) edition of Leaves of Grass. Retrieved from Washington D.C.: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002710162/.

Sandberg, Carl. (1914). “Chicago.” In Poetry: Magazine of Verse. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/12840/chicago.

Whitman, W. (1891). “A Noiseless Patient Spider.” In Leaves of Grass. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45473/a-noiseless-patient-spider.

Whitman, W. (1892). Song of Myself. In Leaves of Grass. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45477/song-of-myself-1892-version.

A) a reaction against Neo-Classical Reason that seeks to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom. B) as an aesthetic, a rejection of strict artistic rules and convention in favor of organic form and innovation. C) often, advocacy for folk traditions that have been despised by classical elites

art that seeks to recover the values and techniques of a classical past, generally emphasizing conventional rules, mathematical precision, and reason over passion. Dominant in Europe during the 18th and early 19th Centuries.

a disciplined pattern of sound units throughout the lines of a poem. In English verse, meter is found in the number and a pattern of stressed and un-stressed syllables in a line

a pattern of repeated sounds, usually the final syllable in the ends of verse lines

within a poem, a repeated pattern of sounds that end lines, defining stanzaic boundaries and shaping a poem’s themes. Designated for analysis by letters: e.g. a-b-a-b, in which a-lines and b-lines end in rhyming words.

a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms

a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses: e.g. “I have a dream …” phrase repeated in Dr. Mar-tin Luther King’s speech, (8/28/1963).

a rhetorical figure that rhythmically lists examples of a category to build in-tensity and emphasis. Common in epic poetry and in free verse in the tradition of Walt Whitman

(in French, "vers libre") poetry that achieves verbal rhythms through repetitive, often parallel figures of speech, Tropes and Schemes. Free verse does not establish set patterns of meter or rhyme.

committed to the late 18th and 19th Century reaction against Neo-Classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom.