15.5 Art and Mortality

Let’s recall the 2nd of the features of a spiritual perspective in the arts: “Yearning to transcend life & death.” Human beings are the animals who know the fate that awaits them. And their art has been looking for a spiritual transcendence throughout the ages.

Gilgamesh and the Search for Immortality

Let’s return one more time to Gilgamesh. We have already explored the journey taken by the hero of Uruk in search for immortality. His journey is spurred by his shock at watching his friend die.

from Tablet IX

Over his friend, Enkidu, Gilgamesh cried bitterly, roaming the wilderness.

“I am going to die!–am I not like Enkidu?!

Deep sadness penetrates my core,

I fear death, and now roam the wilderness–

I will set out to the region of Utanapishtim, son of Ubartutu,

and will go with utmost dispatch!”

from Tablet X

“Enkidu, whom I love deeply, who went through every hardship with me,

the fate of mankind has overtaken him.

Six days and seven nights I mourned over him

and would not allow him to be buried

until a maggot fell out of his nose.

I was terrified by his appearance,

I began to fear death, and so roam the wilderness.

The issue of my friend oppresses me,

so I have been roaming long trails through the wilderness. …

How can I stay silent, how can I be still!

My friend whom I love has turned to clay.

Am I not like him? Will I lie down, never to get up again?”‘

When he finally reaches his ancestor, Utanapishtim, who has been blessed by the gift of immortality, he finds only disappointment. Note that the cuneiform tablets are missing significant text passages.

“Why, Gilgamesh, do you … sadness? …

You have toiled without cease, and what have you got!

Through toil you wear yourself out,

you fill your body with grief,

your long lifetime you are bringing near (to a premature end)!

Mankind, whose offshoot is snapped off like a reed in a canebreak …

No one can see death,

no one can see the face of death,

no one can hear the voice of death,

yet there is savage death that snaps off mankind.

For how long do we build a household?

For how long do we seal a document!

For how long do brothers share the inheritance?

For how long is there to be jealousy in the land(!)!

For how long has the river risen and brought the overflowing waters,

so that dragonflies drift down the river!’

The face that could gaze upon the face of the Sun

has never existed ever.

How alike are the sleeping and the dead.

The image of Death cannot be depicted.'”

Utanapishtim, blessed of the gods with eternal life, does not trust Gilgamesh. He does, however, pity him and offers him a merciful gift.

“Gilgamesh, you came here exhausted and worn out.

What can I give you so you can return to your land?

I will disclose to you a thing that is hidden, Gilgamesh,

I will tell you.

There is a plant… like a boxthorn,

whose thorns will prick your hand like a rose.

If your hands reach that plant you will become a young man again.”

Yet even the gift of the boxthorn is snatched away from a man condemned to the fate of all mortals.

A snake smelled the fragrance of the plant,

silently came up and carried off the plant.

While going back it sloughed off its casing.

At that point Gilgamesh sat down, weeping,

his tears streaming over the side of his nose.

“Counsel me, O ferryman Urshanabi!

For whom have my arms labored, Urshanabi!

For whom has my heart’s blood roiled!

I have not secured any good deed for myself. …

What can I find to serve as a marker for me?”

So Gilgamesh fails in his quest for immortality. Yet the quest has been taken up by culture after culture.

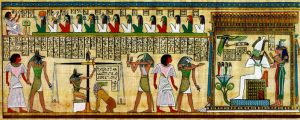

Egyptian Funerary Art: Books of the Dead

Ancient Egyptian art was focused intensely on the quest for immortality. Most of it was funerary, intended for inclusion in tombs. Included inside tombs and the coffins of mummies were papyrus versions of the …

|

| Book of the Dead: Hunefer Papyrus. (c 1310 BCE). Psychostasis scene (judgment before Osiris,) |

Two scenes from the so-called Hunefer Papyrus portray key scenes from the journey. Led by the jackal-headed god Anubis, the soul of the deceased must pass through a gauntlet of examination by “forty-two judges, representing different aspects of Ma’at, Divine Justice.” After pleading innocence to all 42 judges, the soul’s heart is weighed against a feather on a scale. If the heart were laden with sin, the soul would be devoured by the crocodile-headed Ammut. If it passed the test, the soul was presented to Osiris, king of the underworld, and “the deceased would be ushered into the realm of the deities.”

The fully developed Egyptian concept of a judgment in the afterlife was influential in many cultures. Some scholars see parallels in the Christian concept of the day of judgment.

Genteel Death: Emily Dickinson

|

| Portrait of Emily Dickenson. (c 1847). Daguerreotype. |

Emily Dickinson lived a virtually anonymous life in silent resistance to conventional social expectations. At Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, “Dickinson remained seated while everyone else stood” in affirmation of a speaker’s invitation for the women to be Christian. She returned home and lived in seclusion, composing poems destined for letters to friends and her desk drawer. Among her themes was the impossible challenge of imagining death.

Emily Dickinson, Poem 591

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air –

Between the Heaves of Storm –

The Eyes around – had wrung them dry –

And Breaths were gathering firm

For that last Onset – when the King

Be witnessed – in the Room –

I willed my Keepsakes – Signed away

What portion of me be

Assignable – and then it was

There interposed a Fly –

With Blue – uncertain – stumbling Buzz –

Between the light – and me –

And then the Windows failed – and then

I could not see to see –

Dickinson’s verses can seem strange. Who would imagine a fly buzzing in the room at the point of death? Then again, who can imagine the point of one’s own death? Dickinson tackled the challenge of imagining death with the same courage she showed in resisting the social conventions which she found so stifling.

Emily Dickenson, Poem 479

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and Chill –

For only Gossamer[1], my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle[2] –

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice[3] – in the Ground –

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –

In this famous poem, Dickinson imagines death as a genteel suitor calling for her in a carriage bearing her into infinity. Notice the details: the bridal veil, the destination as a swelling in the ground, the absorption of time into a timeless infinity. To suggest the featureless and unknowable, Dickinson catalogues features of daily life her journey leaves behind.

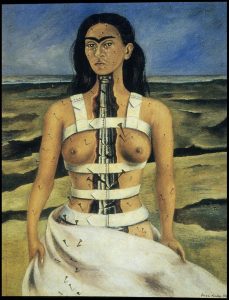

Mortality and the ancestors: Frida Kahlo

|

| Las Dos Fridas [The Two Fridas]. (1939). Oil on canvas |

Frida Kahlo was born in Mexico City to a German immigrant father and a mestizo[1] mother. As an artist, she worked primarily in self-portraits, albeit self-portraits of a unique type. In surreal compositions, she explored her herself internally and externally, probing the textures of her mortality. The Two Fridas reflects a culturally split self, attired in dresses from each culture, with two hearts connected by a tenuous line of blood.

[1] Mestizo: i.e. a Mexican of mixed ethnic origins—European and indigenous

For Kahlo, art was, quite literally, a chronic wrestling with death. After suffering a crushed spine in a bus accident while a teenager, Kahlo endured numerous operation and hospital stays lying flat on her back. She painted in hospital beds, her canvases perched above her. The Broken Column transforms her spinal column, never whole again after the wreck, into art, a Greek architectural column.

|

|

| Broken Column. (1944). Oil on canvas. | El Sueño (La Cama) [The Dream (The Bed)]. (1940). Oil on canvas. |

The Dream (The Bed) uses Surrealist visual logic to evoke a traditional paradox., In traditional cultures, children are conceived and eventually die in beds at home. Recalling that Mexican culture cultivates a very strong, we can see Kahlo’s dream work connecting with those who have gone before her.

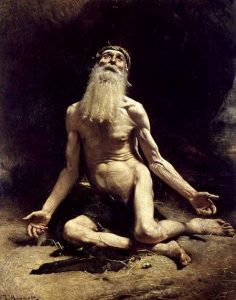

Lamentations of Job

|

| Léon Bonnat. (c. 1860). Job. Oil on canvas. |

Christian spirituality grew out of that of the Hebrews, their scriptures, and their temple worship. However, the two versions of the faith differ notably in their view of the afterlife. Jewish tradition did not say much about heaven or hell. But we do find in Hebrew scripture a stirring affirmation of our hope of eternal life.

Job is a wise and righteous man whose faith is tested by bad fortune. He loses his herds, his children and his health. Worst of all, his friends conclude that his misfortunes MUST indicate that God is punishing him. Job persists and continues to assert his faithfulness even in a disputation with God himself.

Yet Job, in the depth of his suffering, answers the universal human mystery of mortality with a ringing avowal of trust in God’s eternal life.

Lamentations of Job 19.25-27

and that at the last he will stand upon the earth;

and after my skin has been thus destroyed,

then in my flesh I shall see God,

whom I shall see on my side,

and my eyes shall behold, and not another.

The Death of Death: John Donne

Like Job, John Donne finds in his faith a stirring response to death. After a secular career, Donne in 1621 entered the clergy as Dean of St. Paul’s cathedral. In 1623, he contracted an illness that brought him near to death. In 1624, Donne published a series of reflections on his near-death experience. Meditation XVII attempts to bridge the gap between someone else’s funeral bells and our own mortality:

John Donne. (1624). from Meditation XVII, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions.

Perchance he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill, as that he knows not it tolls for him. … The church is Catholic, universal, so are all her actions; all that she does belongs to all. … When she buries a man, that action concerns me: all mankind is of one author. … As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come, so this bell calls us all; but how much more me, who am brought so near the door by this sickness. …

If we understand aright the dignity of this bell that tolls for our evening prayer, we would be glad to make it ours by rising early, in that application, that it might be ours as well as his, whose indeed it is. The bell doth toll for him that thinks it doth; and though it intermit again, yet from that minute that that occasion wrought upon him, he is united to God.

Who bends not his ear to any bell which upon any occasion rings? but who can remove it from that bell which is passing a piece of himself out of this world? No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

Never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee. In these famous words, Donne offers a literary memento mori, the medieval practice of keeping a skull on one’s desk as a reminder of death. In this Holy Sonnet, he celebrates the triumph of faith over death.

John Donne. (1633). Holy Sonnet #10.

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy[1] or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

[1] Poppy: in Donne’s time, poppy seeds were taken to dull pain and to help one fall asleep.

Reading Donne is always a challenge, but perhaps you are more prepared now to track the themes of the English sonnet. Stanzas 1 through 3 each answer the apparent power of death through comparisons which show its weakness. That final couplet embraces the triumph of Christian faith: the death of death in Christ.

Now, the ancestor of Gilgamesh, Utanapishtim, judges that “the image of Death cannot be depicted.” In our final chapter, we will see one of the world’s great writers take on the challenge of doing just that.

Vital Questions

Context

Chapter 15 explores spiritual challenges and visions shared by cultures throughout the world. Obviously, culture matters in each manifestation of these concerns. The hands on the ancient rock faces of caves. The sojourn of Gilgamesh. Chinese landscape images of enlightenment. Photographic images of the sublime. Egyptian books of the dead. Each vision of the is shaped and coded by its cultural context.

Yet speaking of the spiritual, we could speak of the context we all share, that of the human heart.

Content

So what content can we ascribe to the arts’ expression of the yearning we all share? Well, let’s return to our definition of the spiritual:

Evocation of a mysterious human inwardness …

Yearning to transcend life & death …

And connect with forces of creation

Form

Since our scope is so enormous in this chapter, it is difficult to pin down formal features shared by arts from many cultures expressed in a wide variety of media and genres. Looking for the spiritual, we can, perhaps, alert ourselves for forms that break with expectations. We often find the spiritual in forms and styles that carry us out of the known, the familiar, and open Sublime gaps in the apparently seamless surface of our worlds. The arts have a way of finding the spiritual in what Hopkins celebrated in “Pied Beauty.”

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

References

Bonnat, Léon (c. 1860). Job [Painting]. Bayonne, FR: Musée Bonnat. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/leon-bonnat/job-1880

Dickinson, E. (circa 1868). Poem 479. In R. W. Franklin (Ed.), (1999) The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47652/because-i-could-not-stop-for-death-479.

Dickinson, E. (circa 1868). Poem 591. In R. W. Franklin (Ed.), (1999) The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45703/i-heard-a-fly-buzz-when-i-died-591

Dickinson, Emily [Article]. (2005). In Parini, J and Leininger, P. W. The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195156539.001.0001/acref-9780195156539-e-0065.

Donne, J. (1624). Meditation XVII. Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions. Project Gutenberg https://www.gutenberg.org/files/23772/23772-h/23772-h.htm

Donne, J. (1633). Poem #10. In Holy Sonnets. In Holy Sonnets. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44107/holy-sonnets-death-be-not-proud

Epic of Gilgamesh. (c 2750 BCE). Kovacs, M. G, [Trans. Electronic Edition (I998). Academy of Ancient Texts, http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/

Hopkins, G. M. (1877). Pied Beauty [Poem] Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44399/pied-beauty

Kahlo, Frida [Article]. (2016). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-1835

Kahlo, Frida. (1944). Broken Column. [Painting]. Mexico City, Mexico: Museo Dolores Olmedo Patino. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/frida-kahlo/the-broken-column-1944

Kahlo, Frida. (1939). Las Dos Fridas (The Two Fridas). Oil on canvas. Mexico City, Mexico: Museo De Arte Moderno. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/frida-kahlo/the-two-fridas-1939

Kahlo, Frida. (1943). Roots. Private Collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/frida-kahlo/roots-1943

Kahlo, Frida. (1940). El Sueño (or La Cama) [The Dream (or The Bed)]. Oil on canvas. Private collection. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/frida-kahlo/the-dream-the-bed-1940

Kete Asante, M. (2010). Book of the Dead. In F. Abiola Irele & B. Jeyifo (Ed.s), The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195334739.001.0001/acref-9780195334739-e-078

McQuade, M. (2004). Dickinson, Emily. In J. Parini & P.W. Leininger (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195156539.001.0001/acref-9780195156539-e-0065

Emily Dickinson [Photograph]. (1847). Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emily_Dickinson#/media/File:Black-white_photograph_of_Emily_Dickinson2.png

Psychostasis scene (judgment of the dead before Osiris, god of the underworld) [Ink on papyrus]. (c 1310 BCE). Frame 3. Book of the Dead: Hunefer Papyrus. London, UK: British Museum. EA9901,3. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA9901-3