15.2 Art and Christian Faith

So, art and the spiritual. Obviously, thinking of spirituality, most people think primarily of religion. For many students at Bethel University, that means Christianity. And the Jewish-Christian heritage, as we have been learning, abounds with artistic expression.

The Good Shepherd: Psalm 23

The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures;

he leads me beside still waters;

he restores my soul.

He leads me in right paths

for his name’s sake.

Even though I walk through the darkest valley,

I fear no evil; for you are with me;

your rod and your staff—

they comfort me.

You prepare a table before me

in the presence of my enemies;

you anoint my head with oil;

my cup overflows.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me

all the days of my life,

and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord

my whole life long.

Psalm 23 probes the spiritual dimensions we find in art: human inwardness, transcendence of life and death, connection with forces of creation. You may be surprised to find the familiar King James formulation, “valley of the shadow of death,” missing. Modern translations don’t use it. Hebrew scripture offered a more ambiguous vision of the afterlife than does the New Testament. Still, the spiritual images of trust in communion with God are unmistakable.

Spirit and Art: Early and Byzantine Churches

We have already explored the visual art of the early church and its later transformation. The ethos of the small faith gatherings in people’s homes that comprised Christianity in the first two centuries was one of humility, grace, and care for the fragile. Jesus referred to Himself as the Good Shepherd (e.g. John 10:11-18). The slaves, working people, and vulnerable women who swelled these faith communities embraced a nurturing image of Christ’s grace, favoring it on the walls and ceilings of their catacomb graves.

|

|

| Christ the Good Shepherd. (3rd C). Catacomb Fresco. | Christ the Redeemer. (548 CE). Apse Vault Mosaic. |

We have already seen that the concept of Christ was radically transformed by the 4th Century alliance between Christian bishops and the Roman Empire. By the 6th Century, the Emperor Justinian was sponsoring that lavish display of mosaics in a basilica in Ravenna, the seat of power that he had recovered in brutal wars against the Goths. Christ here is depicted as a Roman Emperor clothed in imperial purple.

It is worth considering the relationship between art and the form of one’s faith. Few worshippers in 6th Century could read or had ever traveled. This image of a regal Christ shaped their image of their emperor and of their faith, including their relationship to priests and bishops.

|

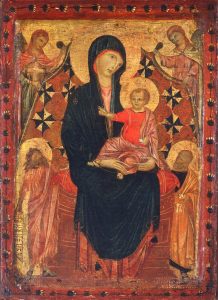

| Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. Tempera on Panel. |

Through the centuries dominated by Byzantine images of Christ, Mary, saints, and angels, the timeless style of the art reflected a faith that rigorously subordinated the human to the theologies and rituals of an authoritative faith. The spiritual impulse seeks to transcend the limitations of the known world. Icons, altar pieces, and books of hours carried Christians’ imaginations beyond the cares and passions of the world to a peaceful realm of pure, faithful communion with God.

Caravaggio: Doubt and Repentance

And then came the Renaissance. We have seen that Renaissance Humanism turned people’s attentions back to the world of human affairs. For Michelangelo, that mean an exalted vision of the human being as God’s greatest creation. Yet, in later life, the great sculptor witnessed the convulsions of the Reformation and his faith and art began to darken.

By the 17th Century, Christian art had begun to turn inward. But then, that is, after all, a crucial dimension of the spirit. Human beings carry at all times an inwardness that seems connected to forces of creation. Prayer. Meditation. Reflection. Every tradition of spiritual discipline carries one outside oneself through portals that open within.

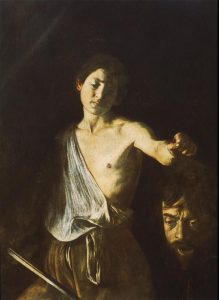

Caravaggio was not a nice man. His life was steeped in vices and wickedness. Yet he composed some of the more powerfully spiritual images ever made. Is this a paradox? Well, sin is, after all, a spiritual dimension of life. Led by Caravaggio, Catholic Baroque artists began to probe not the glory of God’s human creation, but its inner darkness. We have already said that Caravaggio’s 1610 painting of David’s triumph is an act of ritual confession: the severed head of Goliath is Caravaggio’s own self-portrait.

|

| Caravaggio. (1609-1610). David with the Head of Goliath. Oil on canvas. |

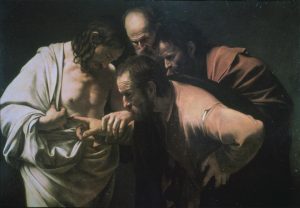

But Caravaggio does not stop at confession of sin. His Incredulity of Saint Thomas is one of the most vivid depictions of Christian faith ever composed. Think about the fundamental paradox of the faith: our decaying, fleshly bodies are suffused with immortal spirit that, the faith promises, will lead one day to resurrection:

This is Christian Theology 101 and it provides comfort to us as we face mortality. But think of the challenge faced by Thomas. He was asked to believe that a man he had walked, talked, and eaten, a dead man whose body he had seen, was alive again. A resurrected body … right now! Not in some far-off day. How many of us would have asked for proof: “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe” (John 20.24). Believe what? That the day of intersection between body and eternal spirit is this day, to be known in this man. Caravaggio got the profound spiritual dimensions of this moment.

|

| Caravaggio. (c 1601-1602). Incredulity of Saint Thomas. Oil on canvas. |

The spiritual is a yearning for transcendence of life and death in a connection with forces of creation. How much faith is required to actually embrace that moment incarnated in a resurrected body? Caravaggio captures the challenge in the furrowed brows of Thomas and the other disciples.

Let’s take things a step further. Consider the general mystery of the human body. I look inwardly into my mind and heart, but what mystery gives life to this flesh in which I live and move? In a day when no one could imagine surgery or dissection, Thomas reaches forward a tentative finger and probes the mystery which remains mysterious even in an age of routine and mechanized surgeries. He touches the very quick of the tissues that live within us.

Caravaggio was a great sinner. He also painted with an all but unmatched awareness of the spiritual.

Anne Bradstreet: Night Prayers

The last time we met Anne Bradstreet, she was a Puritan immigrant to Massachusetts colony who had something to say about the love she shared with her husband. In “By Night when Others Slept,” Bradstreet shares with all humanity that lonely vigil that we know when we cannot sleep. Disturbed by fears and anxieties, we yearn to be connected with a grounding spirit of grace. Bradstreet does not, as she says, wait in vain.

Anne Bradstreet. (1630). By Night when Others Slept.

1

By night when others soundly slept

And hath at once both ease and Rest,

My waking eyes were open kept

And so to lie[1] I found it best.

2

I sought him whom my Soul did Love,

With tears I sought him earnestly.

He bow’d his ear down from Above.

In vain I did not seek or cry.[2]

3

My hungry Soul he fill’d with Good;

He in his Bottle put my tears,

My smarting wounds washt in his blood,

And banisht thence my Doubts and fears.

4

What to my Saviour shall I give

Who freely hath done this for me?

I’ll serve him here whilst I shall live

And Loue[3] him to Eternity.

Rembrandt’s Night Watches

Rembrandt van Rijn is perhaps most famous for portraits and corporation paintings such as the massive canvas traditionally but mistakenly known as The Night Watch. As a Dutch painter working in Reformed Holland, he was not commissioned to paint massive icons and altar pieces featuring saints and angels.

However, Rembrandt devoted a great many of his compositions to his faith. We have already seen his depiction of the Sublime and of grace in his Storm on the Sea of Galilee.

|

|

|

| Storm on Sea of Galilee. (c 1633). Oil on canvas. | The Lamentation over the Dead Christ. (1635). [Painting]. Oil on paper, pieces of canvas | Philosopher in Meditation. (1632). Oil on wood. |

In Rembrandt’s Christian compositions, we see a quiet, reflective spirituality, less showy, less doctrinaire than traditional Catholic art. His Lamentation is one of hundreds of examples of the Pieta. Its composition, however, challenges a conventional reading.

Rembrandt, child of both Catholic and Reformed parents, splits the difference between Protestant and Catholic renderings of the cross. The cross itself, soaring into the dark heavens and dominating the composition, is empty, as is customary in Protestant renderings. But, emulating the Catholic Crucifix, the body of Christ remains in the lower right, lit but blending almost imperceptibly into the bodies of the disciples. The dark, monochromatic color scheme creates a somber mood while obscuring the theological details normally found in such compositions.

Rembrandt’s obscure technique invites us into deep but not necessarily determined spiritual reflection. His Philosopher in Meditation samples the spiritual reflection shared by everyone, sacred or secular, Christian or otherwise who looks within for the light piercing the gloom of human foreboding.

Hopkins: Muscular Faith in Art

We often turn to religious verse that comfortably leads us into devotional grace. But, as we see in Caravaggio, Christian spirituality includes challenge as well as relief. Some Christian poets call us to develop our spiritual muscles by working through challenging verses.

We have met Father Gerard Manley Hopkins before. An Anglo-Catholic priest, he worked out the challenges in his own faith by tramping through the woods and finding flashes of the elusive spirit of Christ in surprising places. In “Pied Beauty,” he challenges the conventional habit of making art, especially religious art, out of idealized images of regularity and Classical beauty.

Warning. This poem will challenge you. The multiple notes reflect its embedment in a long-gone agrarian society. Moreover, Hopkins challenges our rhythmic ears with muscular meter that, like jazz music, knocks us off stride. Still, give the lyric a chance. Read aloud and try to see images and objects of irregularity.

Gerard Manley Hopkins. (1877). Pied[1] Beauty

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded[2] cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple[3] upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls;[4] finches’ wings;[5]

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;[6]

And áll trádes,[7] their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter,[8] original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

[1] Pied: i.e. spotted, uneven in color

[2] Brinded: i.e. a cow with splotches of coloring

[3] Stipple: flecked bits of color or shade that flash out from the scales of trout

[4] Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls: the image of fallen chestnuts that look like burning coals

[5] Finch’s wings: iridescent flashes of brilliant color from birds’ feathers

[6] Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough: reference to the traditional farming method which rotated thirds of the available land—1/3 folded over, 1/3 left fallow, and 1/3 planted

[7] áll trádes: a sudden shift away from nature and to the tools that make human artifice possible

[8] Counter: i.e. against conventional expectation

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Ultimately, the poem’s theme is simple, though paradoxical. God has a changeless, timeless, perfect beauty. But if we have the spiritual eyes to see, we can see the glory of that unified beauty in a boundless creativity that keeps producing irregular, diverse creations that cast off surprising glimpses of glory.

We have no time to do it justice, but Hopkins’ rhythmic power and creativity is almost unmatched in English verse. Notice the accents: e.g. áll trádes. Hopkins wants to be sure we place the accent on the syllables of his choice. He intends us to notice the unconventional abundance of stressed syllables: swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim. A Spondee is a foot with two stressed syllables. It slows the rhythm and hammers the significance of word after word. As his poem approaches its end, these pied departures from “normal” meter force us to lock in on the diversity of God’s world—swift/slow; sweet/sour; dazzling/dim.

It’s a challenge, but can you hear, see, and grasp it?

Can you handle one more? “The Windover” is one of the most intense, richly layered lyrics in the English language. As a poem, it challenges our reading skills. But it packs a spiritual punch deriving from a simple moment: a meditative, observant man watching a hawk fly.

Gerard Manley Hopkins (May 30, 1877). “The Windover.

To Christ our Lord

I caught this morning morning’s minion,[1] king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin,[2] dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon,[3] in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein[4] of a wimpling[5] wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend:[6] the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valor and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier![7]

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion[8]

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall[9] themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

[1] Minion: in medieval times, a loyal servant or a loved one

[2] Dauphin: French feudal title roughly synonymous with prince, the heir to the throne

[3] Falcon: a Windhover is a kestrel or small falcon, a bird of prey

[4] Rung upon the rein: a not particularly precise phrase which nevertheless suggests spiraling flight turning on the wing as a horse might be drawn in a circle by a trainer’s bridle

[5] Wimpling: a wimple is cloth headdress worn by nuns and, in medieval times, by modest married women. Wimpling refers to the undulations and rippling corresponding to a wimple’s folds. Thus air pressure causes the windhover’s wings to ripple.

[6] a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: another image of controlled, arcing movement, a skater arcing on the ice

[7] Chevallier: French for knight, a horseman devoted to a noble cause

[8] Plough down sillion: in this poem, Hopkins revived an archaic word, sillion, referring to the furrow left by a plough.

[9] Gall: harass, trouble, chafe, exasperate

Our footnotes—glosses—testify to the poem’s elusiveness. Yet it’s not that hard to grasp. Lines 1-11 paint a vivid picture, a falcon’s majesty, wheeling, soaring in flight, linked rhetorically to royal splendor. The poet, his “heart in hiding,” is stirred, inspired by the “achieve of, the mastery of” the bird’s aeronautical skill, testimony to the so easily missed glory of God.

In the final lines, we are stirred by Hopkins’ favorite theme, divine glory in unexpected places. A ploughman follows a horse in a “shéer plod.” Yet, in the turned up clay, the plough leaves behind a flashing, multi-colored sheen. As a wood fire burns down, its apparently “blue-bleak” embers ever so briefly gash themselves into God’s “gold-vermilion” splendor.

Hopkins’ metrical play fascinates lovers of muscular poetry. Notice the Alliteration, repeated consonants beginning words: morning morning’s minion; –dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn ; rung upon the rein . Hopkins used the term sprung rhythm to designate his attempt to break the bonds of meter through “writing and scanning by number of stresses rather than by counting syllables (Hopkins, Gerard Manley). Syllables spill over the meter as a jazz musician strays outside the metrical norm with an “excess” flourish of notes:

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding …

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

The syllables in italics pile up, overflowing the meter like Louis Armstrong’s trumpet riffs. The falcon, prince of the morning, holds an arc against the wind, tethered to a single rippling wing, Hopkins’ verse similarly wheels beyond and then back into Meter. Some religious art stirs us, not with the ease of its pieties, but by challenges that call us out of our conventional expectations to glimpse foretastes of eternity.

|

| Kanō Motonobu. (1513). Flowers and Birds of the Four Seasons. |

Like all spiritual experiences, Hopkins’ encounter with the hawk shares a universal human spirituality. Our spirits are similarly lifted by the bird in flight in the screen painting. Flowers and Birds of the Four Seasons combines the elevated spaces of Chinese landscape painting with “landscapes, birds, and figure pieces, chiefly in ink with occasional touches of pale tints” (Kano, family or school of Japanese painters, 2018). This school of art[1] reflects the influence of Zen Buddhism (Japanese Art and Architecture, 2004). We find spiritual inspiration everywhere in art … if we look.

[1] Kano school: named for Kano Masanobu (c.1434–c.1530) and his sons of the Muromachi period of Japanese history.

References

Bradstreet, Anne. (1650). By Night when Others Slept [Poem]. In The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43698/by-night-when-others-soundly-slept

Bray, J. de. (1670). David Playing the Harp [Painting]. Private collection. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:David_Playing_the_Harp_1670_Jan_de_Bray.jpg.

Caravaggio, M. (c 1610). David and Goliath [Painting]. Rome: Galleria Borghese. https://www.collezionegalleriaborghese.it/en/opere/david-with-the-head-of-goliath

Caravaggio, M. (ca. 1601-1602). The Incredulity of Saint Thomas [Painting]. Potsdam, Germany: The New Palace. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caravaggio/incredulity-of-saint-thomas

Christ as Good Shepherd [Fresco]. (3rd C CE). Rome. IT: Catacomba di Callistus; Crypt of Lucina. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Good_shepherd_02b.jpg

Christ the Redeemer [Mosaic]. (548 CE). Apse Vault. Ravenna, Italy: Basilica di San Vitale. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/byzantine-mosaics/st-vitalis-archangel-jesus-christ-second-archangel-and-bishop-of-ravenna-ecclesius-547

Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art. Accession Number 1952.5.60. https://www.nga.gov/artworks/41675-madonna-and-child-saint-john-baptist-saint-peter-and-two-angels

Hopkins, G. M. (1877). Pied Beauty [Poem] Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44399/pied-beauty

Hopkins, G. M. (May 30, 1877). The Windover [Poem]. Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44402/the-windhover

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. (2012). [Article]. In D. Birch & K. Hooper, (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-3719.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. (2012). [Article]. In D. Birch & K. Hooper, (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-3719.

Kanō Motonobu. (1513). Flowers and Birds of the Four Seasons [Painting]. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/kano-motonobu/flowers-and-birds-of-the-four-seasons-1513-1

Portrait of Gerard Manley Hopkins [Photograph]. (n.d.). Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GerardManleyHopkins.jpg.

Rembrandt van Rijn. (1635). The Lamentation over the Dead Christ [Painting]. London, UK: The National Gallery. AN NG43. http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG43

Rembrandt van Rijn. (1632). Philosopher in Meditation [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010062022

Rembrandt. (1633). Storm on Sea of Galilee [Painting]. Boston, MA: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/10953

art styled in the manner of Byzantine icons: depictions of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or saints in a stylized manner—flat, emotionless, timeless, placeless, focused on theological dogma. Common Byzantine media: mosaics, frescoes, paint on panel

A) a 14th Century shift in European culture from a narrow, exclusive focus on scripture and Church interests to a broader interest in cultural traditions, especially those of classical Egypt, Greece and Persia. B) a perspective that values and focuses on the capacities of human beings for knowledge, wisdom, and creativity.

the 17th Century artistic tradition that followed the Renaissance, characterized by gritty social realism, dramatic action, depth of characterization, closed compositions, and intense contrasts between light and shadow. More broadly, any art emulating the values of the Baroque

an aesthetic effect in art in which the viewer or reader experiences awe, even fear in a representation that (safely!) carries the imagination into danger, terror, darkness, solitude, or infinity

a relatively short poem which expresses the deep reflections and poignant emotions of the poetic voice. Origin: the portion of ancient Greek dramas sung to the accompaniment of a lyre (harp).

a metrical foot pairing stressed syllables: e.g. JACK SPRATT … Spondees are generally exceptions to the dominant metrical pattern and serve to slow the rhythm for emphasis.

a figurative scheme in which multiple words in a series repeat initial sounds—usually consonants: e.g. “I hear Lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore” (W. B. Yeats, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” 1888)

a disciplined pattern of sound units throughout the lines of a poem. In English verse, meter is found in the number and a pattern of stressed and un-stressed syllables in a line