14.8 The Great Crash

The brittle optimism of the Roaring 20s shattered in October 1929. Stock markets that had risen to impossible highs based on speculation and fantasy came crashing down. Around the world, companies collapsed, farm prices plummeted, and banks failed. The Great Depression settled in for a run of nearly a decade.

Of course, people on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder suffered soonest and worst. In Harlem, the prosperity that had supported the Renaissance contracted, hurting not only artists and writers, but wage earners as well. Working people all over the country faced long term unemployment without a safety net.

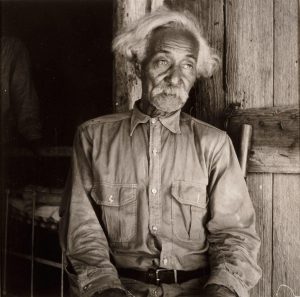

Snapshots of Rural Despair

In 1930, most Americans still lived on farms. “Sharecroppers” worked small farms belonging to landowners and paid rent out of the sale of produce. Most years, the families ended up owing more than they made, leading to long-term debt. Some families had managed to get mortgage loans to buy their land. But a combination of the financial crisis and catastrophic droughts in the American Southwest led to thousands of farms being foreclosed on. Thanks to intrepid photographers, their haunting images remain with us today.

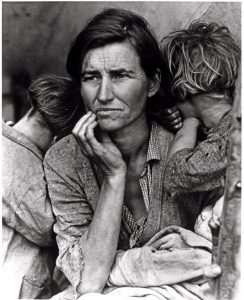

Dorothea Lange

The general affluence of the 1920s supported thriving practices for many portrait photographers. Dorothea Lange’s studio flourished due to her taste in composing faces of loved ones.

The Depression hit photographers as hard as any other profession. Lange began to travel the country, documenting lives of people suffering in a moribund economy. Her photographs shine with dignity and grace. The image of a breadline commemorates nation-wide efforts to feed the hungry.

|

|

|

| Born a Slave. (1933). Gelatin silver print | Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California. (1936). Gelatin silver print. | White Angel Breadline, San Francisco. (1933). Gelatin silver print. |

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

In 1936, the writer and critic James Agee partnered with the photographer Walker Evans to document the lives of the poorest of the poor, sharecroppers eking out their survival in Alabama. The resulting book, Let us now praise Famous Men reflects their patience and persistence in getting to know their subjects and treating their lives with respect.

|

|

| Bud Fields, Hale County, Alabama. (1936). | Bud Fields and his family at home. (1936). |

Agee’s text is notable for the sustained effort he made to beware of the danger of disrespect. He is there to testify to these people’s experience, but he fears he will have betrayed them.

|

|

| Bud Fields’s House Porch with Picked Cotton. (1936). | Kitchen Corner, Tenant Farmhouse. (1936). |

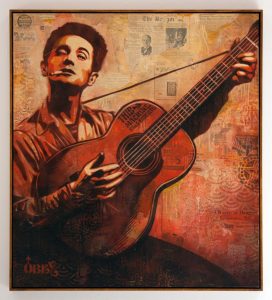

Woody Guthrie

Populations under duress move. In the early 1930s, thousands of victims of poverty hit the road. A subculture of homeless people migrated ceaselessly, creeping onto railroad freight cars and sleeping in shanty towns. One of those “hoboes” could sing and play the guitar.

Woody Guthrie played his guitar and sang his own songs in hundreds of Hoovervilles.[1] Eventually, he found himself singing on the radio and recordings of his songs began to sell. One of his best loved songs is still sung today.

[1] Hoovervilles: shanty towns in which indigent people squatted and survived were derisively named after U. S. President Herbert Hoover who did virtually nothing to alleviate the nation’s economic crisis.

Woody Guthrie. (1940). This Land is Your Land, this land is my land.

1. This land is your land, this land is my land

From California to the New York island,

From the redwood forest to the Gulf Stream waters;

This land was made for you and me.

2. As I was walking that ribbon of highway

I saw above me that endless skyway;

I saw below me that golden valley;

This land was made for you and me.

3. I’ve roamed and rambled and I followed my footsteps

To the sparkling sands of her diamond deserts;

And all around me a voice was sounding;

This land was made for you and me.

4. When the sun came shining, and I was strolling,

And the wheat fields waving and the dust clouds rolling,

As the fog was lifting a voice was chanting:

This land was made for you and me.

|

| Shepard Fairey. (2010). Woody Guthrie. Stencil and mixed media collage on canvas |

Guthrie’s hymn to the beauty of America touches our patriotic hearts. But few people today hear Woody’s real message. Notice the label pasted onto the guitar inf Shepard Fairey’s composition: “This machine kills fascists.” Woody Guthrie’s music was militantly enlisted in a bitter class war between wealthy capitalists and working folk who toiled in unrelieved poverty. The last three stanzas of Woody’s song are little remembered and rarely sung:

5. As I went walking I saw a sign there,

And on the sign it said “No Trespassing.”

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing.

That side was made for you and me.

6. In the shadow of the steeple I saw my people,

By the relief office I seen my people;

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking

Is this land made for you and me?

7. Nobody living can ever stop me,

As I go walking that freedom highway;

Nobody living can ever make me turn back

This land was made for you and me.

Listen to Guthrie singing his bitter hymn to a beautiful land imprisoned by wealth: link.

The song’s final stanzas reveal the bitter irony of its primary theme. This land is—or ought to be—our land, belonging to the people. But it has been purchased and sequestered, leaving thousands to wander without a home. Guthrie celebrates the land and resolves never to leave “freedom’s highway,” but that road is hard and beset with the suffering of the poor.

In 1985, during another time of socio-economic upheaval as the manufacturing base of the American economy was dismantled and discarded, Bruce Springsteen returned to Guthrie’s song. In this linked concert video, Springsteen illuminates our reading of Guthrie’s lyrics and our understanding of the American dream.

The Grapes of Wrath

As drought and poverty raged in the rural districts of the American Southwest, thousands of destitute people packed their meager belongings into clapped out cars and went west. Real estate developers in California were advertising the good life to be found in Los Angeles sunshine. Why, you could reach out and pick an orange from the bounty of trees. Dorothea Lange ironically captures the clash between fantasy and reality in this great migration.

|

| Dorothea Lange. (1933). Heading Towards LA. Gelatin silver print. |

In 1939, John Steinbeck chronicled the journey of the Joad family, typical of the thousands who fled poverty and despair on hardscrabble farms foreclosed by failing banks. Tom Joad, released from prison after killing a man in self-defense, joins his family and becomes involved in union organizing. Caught up in violence once more, he must take to the road, sharing his vision with his grieving mother.

From John Steinbeck. (1939). The Grapes of Wrath.

“You don’t aim to kill nobody, Tom?”

“No. I been thinkin’, long as I’m a outlaw anyways, maybe I could — Hell, I ain’t thought it out clear, Ma. Don’ worry me now. Don’ worry me.”

They sat silent in the coal-black cave of vines. Ma said, “How’m I gonna know ’bout you? They might kill ya an’ I wouldn’ know. They might hurt ya. How’m I gonna know?”

Tom laughed uneasily, “Well, maybe like Casy says, a fella ain’t got a soul of his own, but on’y a piece of a big one — an’ then —”

“Then what, Tom?”

“Then it don’ matter. Then I’ll be all aroun’ in the dark. I’ll be ever’where — wherever you look. Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. If Casy knowed, why, I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad an’ — I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry an’ they know supper’s ready. An’ when our folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build — why, I’ll be there. See?” (Steinbeck, 19, p. 419)

The Specter of Fascism

The Great Depression was a world-wide crisis. Particularly hard hit were Germany and Austria, suffering under the crippling burden of punitive war reparations payments demanded by the bitter victors of World War I. The Weimar Republic, Germany’s fledgling democracy, was roiled by culture wars. Several artistic movements—Die Brücke, DaDa, Bauhaus—explored progressive and socialist ideology and modernist design. But the society was trending strongly to the Fascist Right.

Georg Grosz earned a reputation by composing Caricatures, ironic drawings that distorted a likeness of a person by humorously exaggerating noteworthy features. Grosz used his skills to create Allegories ridiculing the hypocrisy and cruelty of the unholy alliance between capitalism and Fascist ideology which was growing under the leadership of Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Party.

| Georg Grosz. (1926). Pillars of Society. Oil on canvas. |

Of course, the protests of artists could not stop the relentless march of Italy, Germany, Austria into a Fascism that would hurl the world into a second World War that would make the first one look like a picnic. In 1936, a Fascist uprising in Spain triggered a bloody civil war. The German military joined the fight, supporting a Fascist regime and testing its tactics and equipment. On April 26th, 1937, the Luftwaffe[1] bombed the Spanish town of Guernica, killing hundreds, if not thousands of civilians, a foretaste of what was to come.

[1] Luftwaffe: German Air Force

|

| Pablo Picasso. (1939). Guernica. Oil on canvas. |

Pablo Picasso composed Guernica to exorcise his profound distress in reading newspaper articles about the slaughter of his Spanish countrymen and women. Emulating the tones of newsprint, the piece is composed in blacks and grays. Of course, as a protest, Guernica has a Didactic agenda: condemning the war crimes of the Fascist forces. Picasso uses deconstructive techniques to portray the agony of people, children, and animals dismembered by war. Some of the distorted heads expand like balloons, perhaps suggesting the accusing ghosts of the victims. That bull in the upper left has been the subject of many interpretations. It is probably safe to suggest deep links with the Spanish people who love their bulls and who have endured repeated invasions and civil wars for thousands of years. All seems to be contained in a single room with a lone light bulb telling the tale of the atrocity.

Vital Questions

Context

The 20th Century dawned in an era of optimism and confidence in technology, economic development, and human progress. It then descended into the horrors of mass warfare, pandemic, and economic chaos. Artists and writers were there for it all. We have no time to explore the literature and photographic art of World War II or the explosion of artistic modes that emerged in the post-war years. We’ll have to leave our journey through art just as the crises of the 1940s arise.

Content

We can, however, notice the democratization of Content that emerged from the Modern epoch. Literature, art, photography—none of these fields was restricted to Classical elites sequestered from the lives of the many. Lange. Agee. Evans. Guthrie. Steinbeck. These artists’ achievements live on, shining sympathetic light on ordinary, minimally empowered people who resolutely add their songs to the great hymn of humanity.

Form

Art in the last century and our own has known a staggering proliferation of forms. In this section, we see the power of deconstructed images in the protest art or Grosz and Picasso. Documentary photography and Narrative of the Great Depression is more conventional, but formal innovation was growing and accelerating.

If we had the time, would we be ready for an in-depth exploration of the forms to come? Abstract Expressionism? Performance art? Pos-structural Narrative?

I think so. The Formal dimensions of art remain the same. For visual art, Line, Form, Color, Space, Texture. In narrative art, Narration and Story, Point of View. For poetry, Rhythm, Figures of Scheme, Tropes. And always Composition. These core conceptual tools can be brought to bear on any artistic expression.

We will close with a final Module in which we bring our skills to bear on an aspect of art which, for many of us, may be the most important: the Spiritual.

References

Evans, W. (1936). Bud Fields, Hale County, Alabama [Photograph]. Agee, J. and Evans, W. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. (1941). New York: Houghton Mifflin. New York City, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/275866

Evans, W. (1936). Bud Fields and his family at home [Photograph]. Agee, J. and Evans, W. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. (1941). New York: Houghton Mifflin. Rochester, NY: George Eastman House. AN 1976.0009.0004. https://collections.eastman.org/objects/125638/bud-fields-and-his-family-hale-county-alabama?ctx=1a5995da-46d5-4a30-a1d7-ecae02464515&idx=59

Evans, W. (1936). Bud Fields’s House Porch with Picked Cotton, Hale County, Alabama. [Photograph]. Agee, J. and Evans, W. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. (1941). New York: Houghton Mifflin. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 1 994.258.100. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/275516

Evans, W. (1936). Kitchen Corner, Tenant Farmhouse, Hale County, Alabama [Photograph]. Agee, J. and Evans, W. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. (1941). New York: Houghton Mifflin. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 1988.1030. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265903

Fairey, S. (2010). Woody Guthrie. [Collage]. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.10686132 https://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.10686132 stencil and mixed media col

Fairey, Shepard. (2010). Woody Guthrie. [Painting]. Mutual Art. https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Woody-Guthrie–2-/844EB9ACA9153B2260437ECB5DF313CE

Ford, J. [Director]. (1940). The Grapes of Wrath [Film]. 20th Century Fox. Film clip Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4pu0hMs4unk

Grosz, G. (1926). Pillars of Society [Painting]. Lane, M. E. (September 18, 2019). Time. https://time.com/5672506/hitler-art-activism/

Guthrie, W. (1940). “This Land is Your Land.” https://www.woodyguthrie.org/Lyrics/This_Land.htm.

Guthrie, W. (1940). This land is your land [Song]. Woody Guthrie. https://www.woodyguthrie.org/Lyrics/This_Land.htm

Lange, D. (1933). Born a Slave [Photograph]. St. Louis, MO: Saint Louis Art Museum. AN 613:1991 https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/18646/

Lange, D. (1933). Heading Towards LA [Photograph]. Dorothy Lange Digital Archive. https://dorothealange.museumca.org/image/1546/A67.137.94833/

Lange, D. (1936). Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California [Photograph]. Washington DC: Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017762891/

Lange, D. (1933). White Angel Bread Line, San Francisco [Photograph]. Dorothy Lange Digital Archive. Dorothy Lange Digital Archive. https://dorothealange.museumca.org/image/white-angel-bread-line-san-francisco/A67.137.7511/

Picasso, P. (1937). Guernica [Painting]. Madrid, Spain: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/guernica-1937.

Springsteen, Bruce. (September 30, 1985) Performance of “This Land is Your Land.” Live at the Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1yuc4BI5NWU.

Steinbeck, J. (1939). The Grapes of Wrath. New York: Viking Press.

a quality of art that instructs its audience on information, ways of life, or social, moral, religious, or political principles

in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any subject or signification: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement

the “voice” which conveys a story to its audience: a dictating voice, a cinematic camera, a dramatic painting, etc.

a connected series of events and actions that play out in a world projected by a narration

the viewpoint of a work of art’s content imposed on an audience by its structure and composition. In Narrative, the perspective of the narration. In a painting or photograph, the angle and scale from which the subject is depicted.

repeated patterns of expression that enhance the rhetorical effect of the text: e.g. alliteration, anaphora, catalogue, parallelism

a figure of speech that plays on meaning so that the implied message differs from the ordinary sense of the expression. E.g. hyperbole, irony, metaphor, paradox, personification, simile.

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc