14.7 Strange Fruit

The cultural achievements of the writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance offered rare flashes of hope for a people mired in centuries of oppression. In the larger American scene, however, these achievements barely registered. Jazz musicians became household names, but dance bands were not allowed to integrate and, throughout the South, Black musicians could not eat in white restaurants or lodge in white hotels.

|

| William P. Gottlieb (February 1947). Billie Holiday at the Downbeat Jazz Club |

Billy Holiday, nicknamed “Lady Day” by saxophonist Lester Young, was known first in Harlem jazz clubs. Renowned as one of the greatest jazz vocalists, she influenced generations of later singers and transformed such standards as “Lover Man,” “These Foolish Things,” and “Embraceable You.” Holiday was a tough woman not afraid to fight boors and racists. In 1930, Holiday took on the greatest fight of her life.

Abel Meeropol. (1929): “Strange Fruit”

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

“A strange and bitter crop.” What is Abe Meeropole talking about in this gloomy Lyric?

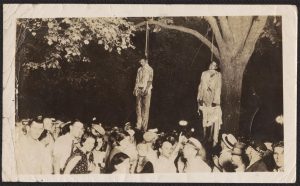

The violence of 1919’s Red Summer didn’t end. Throughout the South and more commonly in the North than people imagined, white mobs lynched African American, hanging them from trees and burning the not necessarily dead bodies with kerosene and matches. If you have the stomach for it, look closely at the faces in the crowd at the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith.

|

| Lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. (1930). Gelatin silver prints. |

Despite their frequency, lynchings were ignored by the mainstream press. Black newspapers and W. E. B. the NAACP’s journal Crisis, edited by Du Bois, strove to raise awareness, but few listened.

Then Lady Day got involved. She adapted Meeropol’s poem as a song and, her heart in her throat, began to sing it in Harlem clubs. Here is a link to her recording of the song: Strange Fruit.

It would be nice to be able to say that Holiday’s recording triggered a transformative awareness across America. It did not. Lynchings continued for decades, into the so-called Civil Rights Era of the 1960s. But Holiday was able to issue a recording of her testimony to the Black experience and we are privileged to hear its sad refrain, a ghostly fragment of our society’s tragic past.

References

Gottlieb. William P. (February 1947). Billie Holiday, Downbeat, New York, N.Y., c. Feb. 1947. [Photograph]. Washington D. C. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. ID LC-GLB23-0425 DLC. https://loc.gov/item/gottlieb.04251.

Holiday, Billie. (1939). “Strange Fruit.” [Song Recording]. Retrieved from http://www.billieholiday.com/portfolio/strange-fruit/.

Lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. (1930). Gelatin silver prints. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Library, Loewentheil Collection of African-American Photographs, #08043. https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/lynching-thomas-shipp-abram-smith-1930/

Meeropol, Abel. (1939). “Strange Fruit.” Retrieved from http://www.billieholiday.com/portfolio/strange-fruit/.